ALAN v31n2 - On the Trail with Jack London: My Journey to Jason's Gold and Down the Yukon

Will Hobbs

On the Trail with Jack London:

My Journey to Jason's Gold and Down the Yukon

I was delighted to return to the ALAN workshop in the fall of '03. It was in my favorite city, San Francisco, a gold rush town as alluded to in the workshop's theme: "Striking it Rich with Young Adult Lit."

What better time to chronicle the writing of my gold rush books?

Jason's Gold and Down the Yukon grew out of an extended trip that my wife, Jean, and I made to Canada's Yukon Territory. We had just gotten off the Takhini River, a tributary of the Yukon River near Whitehorse, and headed north to Dawson City, where we were about to start up a 500-mile gravel road that would take us to within 40 miles of the Arctic Ocean.

I was aware that Dawson City, where the Yukon is met by the clear—running Klondike, was the destination of the Klondike gold rush of the late 1890s. Having no idea what a gift this day would turn out to be, I wandered into Dawson's town museum. I was intranced by the photographs; the Klondike gold rush, I discovered, was extremely well photographed.

One image above all others caught my attention: a photograph of an unbroken line of gold seekers, single file and ant-like—hundreds upon hundreds of them—climbing straight up the icy Chilkoot Pass on the Alaska/ Canada border. The Chilkoot was unbelievably steep, and the stampeders were staggering under huge burdens. I eyeballed the clothes they were wearing. "Hey, wait a minute," I thought. "That's not Gor-tex."

Nearby, I visited the cabin of a world famous author who'd spent a year of his life, at the age of 21, trying to strike it rich in the Klondike. A former teenage oyster pirate from Oakland, California by the name of . . . . Jack London.

I was struck by how little I'd ever known about the Klondike gold rush. Almost nothing. Even though, as a kid, I'd read The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and "To Build a Fire," I had never figured out from reading them what the gold rush was all about. Those stories don't give you the "big picture" of the rush.

What if, I began to think, right there, right then. . . What if I were to go home and learn as much as I could about the Klondike . . . Maybe I could write a story that would give young readers the big picture of the rush. Maybe I could learn all about what Jack London did in the rush, and include him as one of the characters. I could have a fictional kid meet Jack London.

That's how Jason's Gold got started. Back home, I mined a mountain of research. Real-life incidents suggested possibilities left and right. As I started writing, exactly one hundred years after the events I was describing, I was flooded with memories from my childhood in Alaska: larger than life mountains and rivers and bears, glaciers and salmon runs and moose, the winter darkness and the northern lights and rusting gold dredges. It all came together, the landscape and the history and me and Jason: I felt like I was there.

Here's the opening line of Jason's Gold : "When the story broke on the streets of New York, it took off like a wildfire on a windy day."

I wanted this story to imitate the momentum of the gold rush, which was a sort of human wildfire. It began on July 17, 1897, when a ship named the Portland docked in Seattle. Dozens of prospectors disembarked, their suitcases and satchels bulging with gold—all together, two tons of gold.

In an instant, the telegraph wires were humming what the prospectors were shouting: "The Klondike is the richest goldfield in the world!"

In the 1890s, the country was in the throes of a terrible depression. This was an era of robber barons and child labor, hobos riding the rods. At the news of a new gold rush, tens of thousands of people across the continent started making immediate plans.

The geography of the North was poorly understood. At first, most people didn't even know where they were going—Canada, not Alaska. Some were planning, believe it or not, to go by balloon, some by bicycle. A newspaper in Memphis, Tennessee, reported that the Klondike goldfields were "not far northwest of Chicago." That turned out to be . . . incorrect.

The protagonist of Jason's Gold is named Jason Hawthorn. A kid from Seattle, he's on the streets of New York City selling newspapers when the news of the rush breaks. Instantly, he comes down with a bad case of Klondike fever, also called klondic—itis. With ten dollars to his name, Jason hobos his way back to Seattle, then stows away on a steamer bound for the North.

It's going to be rough, just as it was for a hundred thousand people who tried it back in 1897 and '98. Of those 100,000 who set out, around 40,000 actually made it all the way to Dawson City. Jason is going to leave Seattle three days after his brothers, and it's going to take him almost a year to meet up with them in Dawson City. A year was what it took most people to get there.

Jason is going to meet lots of actual, historical figures in their actual, historical context. One of these is Soapy Smith, the infamous con—man from Colorado mining camps who became the "boss of Skagway." Another, of course, is Jack London. Here's some more of what I learned about Jack London's experiences in the North. All of this and much more found its way into Jason's Gold:

Jack London was in the first wave. He left San Francisco only one week after the prospectors from the North arrived on the West Coast. Jack's partner was his 60—year—old brother—in—law. Enroute, they joined up with three other men. Like most people, Jack and his partners chose the Chilkoot Pass as their route to the lakes at the headwaters of the Yukon River.

The Chilkoot was straight up at the last, too steep for horses. At the top of the pass, it was Canada, and the Mounties were weighing supplies. They required that each person bring in 1500 pounds, a year's outfit—they didn't want anyone starving to death.

It was 23 miles to Lake Lindeman, where Jack London and his partners would take down trees and whipsaw lumber and build a skiff capable of withstanding 500 miles of the Yukon River, including the notorious Miles Canyon and the White Horse Rapids.

Jack London knew that most of the stampeders weren't going to beat winter. He did the math. London carried 150 pounds at a time on his back. He weighed 165. Every day, four times, he moved 150 pounds three miles forward.

Jack London and his partners were among only hundreds who made it through that October of 1897, and at the last, they beat the ice by running Miles Canyon and the White Horse Rapids instead of portaging.

Guess what? The former oyster pirate from San Francisco Bay was the man at the stern with the crucial sweep oar.

Jack London suffered a bad case of scurvy that winter, lost some teeth. When break-up came at the end of May, he floated out the 1500 miles to the Pacific on a scow, and worked his way home stoking coal on a steamship.

Did he return with Klondike gold? Yes, he did — four dollars and fifty cents' worth. And plenty of grist for fiction.

Back to Jason. Instead of the Chilkoot, Jason tries the White Pass, theoretically negotiable by horses. He's there as it turns into a quagmire. Three thousand horses died there that fall of '97; it became known as the Dead Horse Trail. Jason rescues a husky from a madman who is drowning his dogs in the creek—an incident from real life, as I explain in the Author's Note.

Jason repairs with the husky to Skagway in order to try the Chilkoot. He gets deathly sick there. Jason wakes up feverish in a strange room where a girl named Jamie and her father, Homer, are taking care of him. They're Canadians planning to canoe the Yukon, which sounds risky in the extreme to Jason. They know what they're doing, Jamie says, and indeed they do. "My father," Jamie says proudly, "is a bush poet. I grew up in the North, in the bush."

Jamie is inspired by a 14-year-old Canadian girl I met who was captaining a canoe on the Nahanni River in Canada's subarctic, the setting of my story, Far North . Like Jack London, Jamie and her father will reappear throughout the story.

Who is Jamie's father inspired by? You guessed it—Robert W. Service, the author of "The Cremation of Sam McGee," a narrative poem of the rush that I've been performing around wilderness campfires since I was fourteen years old.

Jack London and his party are going to beat winter, and so are Jamie and her father. Jason, though, is not going to beat winter. Winter is where the heart of this story lies, so . . . of course . . . I'm not going to tell you about it, other than to say that he and his husky, King, are going to be stuck in a precarious and dangerous situation out in the Great Alone, about halfway down the Yukon to Dawson City. I hope this part of the story gives your readers a good case of virtual frostbite.

When the ice breaks, and Jason makes it to Dawson City, he's going to find that Jamie has become famous performing her father's poetry on the stage of the Palace Grand theater. But she's leaving. It feels like a mortal blow to Jason, who was smitten the day he met her.

With Jason's Gold, I set out to write a story worthy of the rush itself, and I hope I've accomplished that. I hope your readers will be astounded to find out what ordinary people not so different from themselves did a century ago. I hope readers come away with a sense that history can be incredibly exciting, and that life in any era is filled with adventure, heroism, courage, and love.

Well, here I was, all done with Jason's Gold. At that point, I had to face the perennial question, What's next?

I had other projects simmering, but my heart wasn't in them. I was so identified with Jason, I was in limbo wondering if Jamie really was going to come back, as she promised she would.

There was only one way to find out. Write the sequel, you fool, and do it right away! It would be a chance to make hay with the amazing events that came after the summer of '98, when Jason's Gold ends. I could include the Great Fire of April, 1899, in which Dawson's business district burned to the ground at 40 degrees below zero. I could portray the exodus from Dawson City down the Yukon when breakup came at the end of May. Most exciting of all, I could dramatize the fact that thousands of disappointed Klondikers did not head home immediately. Amazingly, another rush was on. On their way home, thousands were going to have one last fling at Lady Luck.

During the winter, news had reached Dawson of a new strike 1700 miles away on the beaches of the Bering Sea. At a place called Nome, 200 miles across the Norton Sound from the old Russian port of St. Michael, gold had been discovered in the beach sand!

As you've noticed, I love a story with amazing geography. The rush from Dawson to Nome, down the Yukon and all the way across Alaska, then 200 more miles across the Norton Sound, was too wonderful to pass up.

Jamie would indeed return to Dawson, as she promised she would. She and Jason could join the new rush to Nome. This one would be a summer story, and to further differentiate it from Jason's Gold, I would make it a first—person story, with Jason being the narrator. It would have to stand alone, in case the reader hadn't read the previous book.

Jamie and Jason will enter a 1700—mile race, with a $20,000 prize, from the warehouse of the Alaska Commercial Company in Dawson to its warehouse in Nome—a fictional device, as I explain in the Author's Note. They're going to face everything the river and a pair of bad guys can throw at them, and it will be quite a ride. I don't mind telling you that Jason and Jamie are going to paddle into the sunset together. If you like a story with a happy ending, this is the one for you.

Both novels include an Author's Note in which I sort fact from fiction. For more about these books, visit my website, www.WillHobbsAuthor.com . The website contains an interview and photos from my novels, plus many other features.

In between sessions of the 2003 ALAN Workshop Will and Jean Hobbs were gracious enough to share some insights from adventures around the planet and the stories that come out of those experiences.

TAR: In your face–to–face encounters with the wilderness you have rowed your raft through some of the most extreme whitewater in North America, camped and explored in grizzly country in the North, faced squalls at sea and the possibility of a humpback whale breaching from under your kayak. Have you ever thought, "Well, maybe I've written my last book!" Any close calls?

WH: For a moment once, on a backpacking hike in our San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado, I thought a mountain was crashing down on me. Three of us had threaded the needle between two peaks and descended the rockslides in order to fish a lake perched under the summit of Mount Oso. Before we'd even assembled our fishing rods, we witnessed the event that orphaned the grizzly bear cubs in Beardance , written a few years later. By fool's luck, we weren't standing where the mother grizzly in my story was when it happened. That was a rare exception to my general feeling that I'm a lot safer in wild places than on the highway. We're pretty cautious in our approach to running rivers, or when we're in bear country.

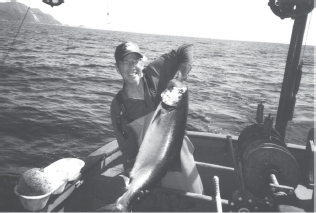

TAR: Many authors research their topics in libraries, on the Internet, or even by visiting the actual setting of their novels and talking with people. Your novels seem to come out of your own personal experience. You and Jean are true adventurers—ten times through the Grand Canyon in your own raft! When you sea kayak the Alaskan coast, or crew on an Alaskan salmon boat, I gather that it's for the experience itself, but then is it afterward that you begin to wonder if there might be a story there?

WH: Yes, that's the way it's always been. I would be doing these same things even if I weren't a writer. This past summer I took an eleven-day trip down a remote river on the north slope of Canada's Yukon Territory. The last night, under the midnight sun, I pitched my tent thirty feet from the Arctic Ocean. I was wishing I could find a way one day to take my readers there, but I don't know if I ever will. More often than not, a story doesn't follow. After our sea kayaking trips, two or three years went by before I thought of the idea for Wild Man Island.

TAR: At ALAN in San Francisco, you said you like to write novels that are "adventure plus." We see you adding a tremendous amount of research to your personal experience in order to write books like Far North, Ghost Canoe, Jason's Gold, Down the Yukon, Wild Man Island, and now Leaving Protection. These are exciting books, yet kids learn a whole lot turning the pages.

WH: I like to write a multi-layered story, to get a number of balls up in the air—it makes it interesting for me and the reader both. I've always thought that novels are a great way for kids to learn content. Novels engage the emotions, and the brain remembers what the heart cares about.

TAR: "Meeting the Challenge" seems to fit you and your work perfectly. What challenges, faced by young people, are you trying to illustrate in your books?

WH: That's a tough one . . . a novelist writes subconsciously, through characters in situations. But looking back, I would say that personal integrity is big in my stories, family and friendship, adapting to change, sorting out what's of value from what is not. I think kids' biggest challenge today is finding a way to believe in hope and possibility, to stay positive and idealistic.

TAR: The 2003 ALAN workshop was entitled, "Striking It Rich with Young Adult Literature." That phrase, "striking it rich," can mean many different things. How do you feel that you have struck it rich in your life?

WH: First of all, I struck it rich with my parents, my three brothers, and my sister. Then my wife, Jean, then all our nieces and nephews:so many shared memories, so many great adventures over the years. Seventeen years of teaching, that was another adventure. The young adult literature in my classroom was my best ally and also my motivation to try it myself. I've been writing full-time for thirteen years now, and it continues to be a dream come true. To hear from kids that your stories have touched them is extremely gratifying. ALAN in San Francisco was a real high point. We treasure our friends who care so much about YA lit, and have done so much to bring it to young readers.

TAR: In the Author's Note at the end of your new novel, Leaving Protection, you talk about your first visit to Prince of Wales Island in southeast Alaska, how the teacher at the middle school in Craig invited you to work on the family salmon troller and to write a novel about commercial fishing in Alaska, a challenge you ended up meeting. How far back does your fascination with those boats and salmon fishing go?

WH: All the way back to my childhood in Alaska, and more recently, to a number of trips through the Inside Passage in southeast Alaska. Those trollers are so picturesque, and I'd always wanted to step aboard one. To have the chance to live on a troller and to do the work of those fishermen was a lifelong dream.

TAR: During a week of king salmon season, no less! If Robbie Daniels' experience as a deck hand in your novel is any indication, this was incredibly hard work.

WH: Oh man, fifteen hours a day's worth. It turned out to be the best king salmon season in many years; sometimes we worked four or five hours before breakfast. A salmon troller, unlike a seiner or a gillnetter, doesn't use nets. The salmon are all caught individually, on lures. Julie and her dad would gaff them and bring them aboard; I did the cleaning and icing. I've done a lot of physical labor in my life, but I hadn't worked that hard since I picked fruit for six weeks with migrants from Mexico when I first got out of college.

TAR: I take it your skipper wasn't anything like the menacing Tor Torsen in the novel.

WH: Not at all, but I did borrow my skipper's knowhow and some of his quirks. For example, when he lay down to sleep, George would be snoring within a minute. He would wake precisely at 4:00 A.M. without an alarm clock.

TAR: Your book explains how it's possible to be a highliner—one of the very best fishermen—and to still be a vanishing breed, due to the effects of dams, logging, and especially salmon farming. For the uninformed, what does the fine print mean when we're looking at a restaurant menu or at the grocery store labels for salmon?

WH: "Wild" is the key word, as opposed to farmed. If it says Alaskan salmon, you know it's wild salmon, since salmon farming is illegal in Alaska. Troll-caught is the highest quality wild salmon; it's cleaned and iced soon after being caught. If the menu says Atlantic salmon, in all likelihood it is farmed. The health and environmental hazards of farmed salmon are getting quite a bit of publicity lately. The huge numbers of lower-priced farmed salmon flooding the market have forced many fishermen out of their livelihood. To give you an idea, George sold his king salmon for half of what he had been able to get, per pound, the previous year. One other note: don't be concerned that by buying wild salmon you are depleting the ocean of wild fish. The catch is monitored so closely to prevent overfishing that some seasons last only a matter of days.

TAR: Did you take notes, with a story in mind, during the seven days you worked on the boat?

WH: Tons of notes, after George was snoring. Everything I was learning was new, and I knew I had to write it down or I would forget it. I was able to follow it up later with telephone interviews with George and Julie and other fishermen I had met, as well as quite a bit of book research. I brought home a bunch of non—fiction books about the trolling life, and they made for good grist to add to the knowledge I had gained first hand. What fueled the book emotionally was the wealth of impressions I came home with that will stick with me forever: the whales and the birds, the light, the beauty of those outermost islands we were looking at, the roll of the swells out there on the open ocean. It was glorious.

TAR: Did your story idea—interweaving the Russian history with the fishing adventure—come as you were cleaning fish or doing that stoop work in the hold?

WH: No, it came by trial and error, as usual, back in my study. Something vital was lacking in my first few approaches to the opening chapters: dramatic tension. Then I got to remembering a metal plate I had seen at the National Historical Park in Sitka, the old Russian capital of Alaska. It was a facsimile of the only possession plaque ever found, one of twenty that the Russians are known to have buried up and down the coast to lay claim to Alaska. It came to me in a flash. What if Tor Torsen, the embittered fisherman, knows where the other nineteen are, and is something of a pirate? Robbie would be in grave danger if he accidentally came across one on Tor's boat. The plaques were the key to dramatic tension across the entire length of the novel. They would also be a way for me to further my longtime interest in the Russians in Alaska, and to pass some of that amazing, little-known history along to my readers.

TAR: One more question. Do you still like eating salmon?

WH: Can't get enough, as long as it's wild. I'm going on two trips to Alaska next summer, one with Jean and the other with one of my brothers. I hope to return to Colorado each time with a box of fillets for our freezer. You're invited to dinner!