ALAN v41n3 - Using The ALAN Review to Help Understand the Past, Present, and Future of YA Literature

Using The ALAN Review to Help Understand the Past, Present, and Future of YA Literature

Wendy Glenn used her Fall 2011 President’s column in The ALAN Review (TAR) to make important observations about the field of young adult literature. For instance, she argued that young adult (YA) authors have always tackled matters of consequence, such as addiction, family dynamics, and gender (p. 7). She noted the field has welcomed new perspectives, specifically from those who have been historically marginalized (p. 8). And, she highlighted the ability of YA authors to use new forms and technologies to engage readers in diversity, culture, and communication (p. 8–9). Her conclusion was that whatever lies around the bend, the YA field was prepared to “withstand the winds of change” (p. 10).

As we consider what lies ahead for the field of YA literature, it is important to pause and take stock of what we currently know. In fact, this was the impetus for an analysis of articles published in The ALAN Review from 2005–2011. The goal of this analysis was to determine whether there were any enduring trends over those seven years and whether there were any key indicators that might help us consider current trends and where the field is heading. Additional value derives from this investigation’s ability to set a meta–analytic baseline, helping us step back and examine who we are and what we write.

Literature syntheses highlight past trends and provide insight into the issues that have been important in the field. They stimulate conversations about what the field has valued and will continue to deem important. Literature reviews can also highlight what is missing from the literature. Acknowledging the gaps in the field’s knowledge base allows the community to consider why these gaps exist and what new questions should be raised. These discussions provide opportunities for reflection on the goals and values of the community. As the leading journal dedicated solely to the scholarship of YA literature, an analysis of The ALAN Review provides an interesting picture of the field’s landscape. Rather than an historical examination of all of the journal’s issues, this review offers a snapshot of a recent timeframe in order to engage the community in conversations about potential avenues of future scholarship.

It is important, also, to remember that discussions of what articles were published in The ALAN Review differ from discussions about what YA literature is being published. While there might be overlap, the mission of The ALAN Review (as published on page 2 of each issue) is to publish “reviews of and articles on literature for adolescents and the teaching of that literature: research studies, papers presented at professional meetings, surveys of the literature, critiques of the literature, articles about authors, comparative studies across genre and/or cultures, articles on ways to teach the literature to adolescents, and interviews of authors” (¶ 2).

In this article, we first present an overview of the categories that emerged within the analysis. We then dive deeper into each category to emphasize trends. The article concludes with a discussion on the future, highlighting implications from each category.

An Overview of TAR articles

There were 229 articles published in The ALAN Review between 2005 and 2011. For this review, “articles” include submitted manuscripts, author interviews, research connections, and the publishers’ connections. Two editorial teams (Goodson & Blasingame until Summer 2009, and Bickmore, Bach, & Hundley beginning Fall 2009) are represented in this review. While the purpose of a peer–reviewed journal is to have a representative body of work, editorial teams often guide the direction of the journal. Therefore, The ALAN Review not only represents a slice of what YA literature is being published, but also the scholarship surrounding YA literature and the decisions of the editorial team, including those who review for the journal.

In order to complete this literature synthesis, we spent a significant amount of time re–reading each article, creating categories, reviewing categories, and assigning the reviews to categories. We asked ourselves: What is the focus of the article? What is the author trying to communicate to readers? What are the goals of the article? We used these questions to guide our placement of articles. For instance, Daniels ( 2006 ) discussed how literary theories could be used to analyze YA literature. We assigned Daniels article to a category called Theory. We then moved to the next article, constantly comparing our category assignments and definitions as we progressed.

This led to an arranging and rearranging of not only the articles, but the categories themselves. For example, initially we had the following categories: 1) Using YA literature in schools and libraries, 2) Engaging young adults in YA literature, 3) Using YA literature with preservice and inservice teachers, and 4) instructional approaches for YA literature. As we looked across these categories, we recognized the articles had the similar goal of engaging readers in YA literature. We decided to collapse these categories into one section, Engagement , so that we could examine if there were similarities in how educators and librarians were engaging readers in YA literature across contexts and age groups.

The obvious danger in such a broad categorization scheme is that one article might fit multiple categories; therefore, articles might have a similar focus but be in separate sections. For example, we placed Adomat’s ( 2009 ) article featuring YA books with young adults with disabilities in the Adolescents’ Lives category, while Menchetti, Plattos, and Carroll’s ( 2011 ) article that explored preservice teachers’ interactions with YA literature that featured young adults with disabilities was placed in Engagement . In this particular case, we made this distinction by asking ourselves, “Was the author trying to provide insight on YA novels that focus on adolescents’ lives or was the goal to examine instructional approaches and implications?” Our thinking behind this specific decision was that Adomat’s article examined the YA books themselves, and Menchetti et al.’s article examined preservice teachers’ interactions or engagement during reading. In order to make the placement, we consistently went back to reflecting on the main goals for the article and the author’s rationale for the article.

After reviewing all 229 articles, seven categories emerged:

- Adolescents’ Lives: Articles that address specific aspects of YA literature and young lives (e.g., depression or pregnancy). These articles examine particular issues present in adolescents’ lives, events that impact their lives, and also how young adults identify themselves and these representations of identity in YA literature.

- Diverse Perspectives: Articles focusing on YA literature that presents diversity. While this category might seem similar to adolescents’ lives, these articles emphasize how particular cultures are represented in YA literature.

- Engagement: Articles that highlight the use of YA literature for engagement. The articles in this section explore the places and ways educators and librarians engage students in YA literature.

- Forms, Formats, and Genres: Articles that specifically examine genres, forms, and formats.

- Important People: Articles about or interviews with YA authors or those who influence YA literature.

- Significance of YA Lit: Articles about the past and present significance of YA literature.

- Theory: Articles that address theoretical perspectives or analyses of YA literature.

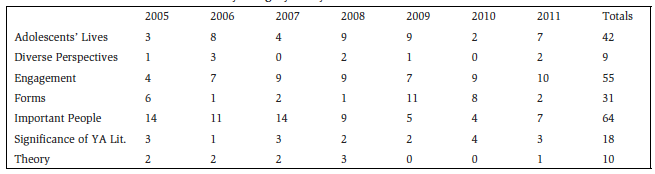

Table 1 highlights the categories and the total number of published contributions between 2005 and 2011; it also reports publications by year. If one were to examine the field by looking at the major categories of articles published in The ALAN Review , one could conclude that we (researchers and educators in the field) have consistently appreciated the role of YA literature in Adolescents’ Lives . We have also begun a strong trend toward understanding how young adults are reading and Engaged in YA literature both in and out of school. Forms is an area that has been important in some years and not in others. We have paid less attention recently to the Important People in our field, at least in writing about them the last few years. And, although we and other organizations within our field have called for the importance of Diverse Perspective , the Significance of YA Literature , and the use of Theory to understand YA literature, it has not necessarily been a topic of focus in ALAN publications. This could be because all three play significant and ubiquitous roles in all publications, regardless of the overarching theme of the article. To answer these questions, we dug deeper into the articles published within each of these broader categories.

Breakdown by Category

Adolescents’ Lives

Literature is often referred to as a window, a way for readers to reflect on life events and learn more about themselves. Many members of ALAN work closely with young adults and are thus thoughtful about the literature that speaks to their lives. This category (18.34%) examines articles written about young adults and the topics in YA literature considered relevant to their lives.

Over the seven years used for this analysis, the most written about issues were those surrounding sex, whether it be identification (gender), the consequence of the physical act of sex (pregnancy and parenthood), or orientation (LGBTQ). From 2005–2009, there was a significant focus on gender, sexual activity, and pregnancy. Authors examined particular titles that might speak to the female experience ( Blackford, 2005 ; O’Quinn, 2008 ; Robillard, 2009 ; Sprague, Keeling, & Lawrence, 2006 ) or male experience ( Glenn, 2006 ; Jeffery, 2009 ; Kahn & Wachholz, 2006 ; Madill, 2008 ). These articles raised questions about how we as adults select books based on gender and how these books may or may not perpetuate assumptions about femininity and masculinity. Tied to this theme were articles focused on sex, pregnancy, and parenthood. Over the course of four years (2005–2009), there were 6 articles about how the experience of pregnancy and parenthood was portrayed in young adult literature. The word “real” is used multiple times, by either the authors ( Bittel, 2009 ) or pregnant/parenting teens ( Hallman, 2009 ). These articles highlight the tension that exists between not wanting to misrepresent the experiences of teenage parents and the moral tensions that authors may face.

Table 1.

A breakdown of

TAR

articles by category and year

Beginning in 2008, there was a surge in articles written about young adult literature with a Lesbian, Gay, Bi–Sexual, Transgendered, or Questioning (LGBTQ) perspective. This category had 8 articles published within the shortest time period (2008–2011). These articles advocate for young adults to read literature in which a character identifies as LGBTQ to help establish acceptance and understanding for young adults of all sexual orientations. The authors of these articles assert that LGBTQ literature is critically important because, as Hayn and Hazlet ( 2008 ) contend, “[T}alking openly about homosexuality in schools may be the one area of diversity still unaddressed” (p. 66).

Adolescence as a time of identity formation and coming–of–age was explored in 6 articles from 2006– 2011. Authors examined ways that young adults might seek an identity and how “non–conformist” ( Jones, 2006 ) YA literature might help young adults explore this idea of “self” ( Bell, 2011 ; Insenga, 2011 ; Jones, 2006 ; Lautenbach, 2007 ; Zitlow & Stove, 2011 ).

While issues of sexual orientation, gender, sex, and identity represent young adults’ lives on a very personal level, beginning in 2005 and spanning through 2011, authors also looked at young adults’ lives on a more global scale. Throughout this time span, we found articles about war ( Caillouet, 2005 ; Franzak, 2009 ), terrorism ( Hauschildt, 2006 ), social inequalities ( Tuccillo, 2006 ), genocide ( Bannon, 2008 ), religion ( Smith, 2009 ), and urban settings ( Thomas, 2011 ) in young adult literature. The focus on these topics coincided with events like 9/11 and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

While the topics mentioned above found the most space in the pages of The ALAN Review , there were other topics covered that received less attention. For example, although adults often have important roles in YA literature, there were only 3 articles that provided an in–depth examination into their roles in YA literature ( Town, 2006 ; Vincent, 2008 ; Cummins, 2011 ). Similarly, few articles examined health–related issues. For example, over the past seven years only 3 articles explored how young adults with disabilities are portrayed in YA literature ( Adomat, 2009 ; Crandall, 2009 ; Pajka–West, 2007 ). Issues like body image ( Quick, 2008 ) and mental health concerns ( Phillips, 2005 ) lacked a strong voice. And surprisingly, despite the amount of media coverage surrounding incidents of bullying in schools, only 1 article focused on bullying in YA literature from 2005–2011 ( Bott, Garden, Jones, & Peters, 2007 ).

Diverse Perspectives

Literature has the power to shape lives by providing insights on humanity, culture, and experiences. Readers can grow to know someone, something, or someplace quite different. The category of diverse perspectives is made up of articles that present and advocate for YA literature representing diverse populations of people. Although the total number is small, 9 total (3.9%), these articles were distributed somewhat evenly over the time frame of 2005–2011. Except for 2010, each year offered at least 1 article examining diverse perspectives in YA literature. These articles examined representations of culture and considered whether stereotypes were being perpetuated through these texts. This required an examination of how the novel was crafted and how certain ideologies were represented.

Authors examined literature that included Native American (Bickmore, 2005; Metzger & Kelleher, 2008), Asian American ( Loh, 2006 ), Mexican American ( Saldaña, 2012 ), Hawaiian ( Bean, 2008 ), and Latina ( Medina, 2006 ) voices. Authors also examined literature portraying young adults who live outside of the United States ( Kaywell, Kelley, Edge, McCoy, & Steinberg, 2006 ; Miskin, 2011 ; Westenskow, 2009 ).

Engagement

Engagement in YA Literature contained a total of 55 articles (24%) spanning from 2005–2011. The purpose of this category was to examine how young adults are interacting with YA literature, the spaces created in schools and libraries for reading, and specific instructional approaches used to engage young adults in reading YA literature.

Four specific subcategories emerged within Engagement . First, beginning in 2007, 15 articles featured instructional approaches for teaching specific books . For example, Gold, Caillouet, and Fick ( 2007 ) examined wordplay in Holes (Sachar, 1998). Other articles examined titles such as Julia Scheere’s Jesus Land ( Scherif, Arteta–Durini, McGartlin, Stults, Welsh, & White, 2008 ), Sharon Creech’s The wanderer ( Gold, Caillouet, Holland, & Fick, 2009 ) and M. T. Anderson’s Feed ( O’Quinn & Atwell, 2010 ). Articles about instruction often focused on specific topics. For instance, 3 articles explored how to teach YA literature with diverse perspectives ( Bloem, 2011 ; Kuo & Alsup, 2010 ; White–Kaulaity, 2006 ). Nine articles in this subcategory were about instructing a diverse group of adolescents. This included students who are incarcerated ( Baer, 2011 ; Greinke, 2007 ), adolescents considered at–risk ( Vasquez, 2009 ), and adolescents in AP English programs ( Miller & Slifkin, 2010 ). Finally, there were articles about instruction that focused on instructors. Two articles examined preservice teachers’ interactions with YA literature in teacher education courses ( Menchetti et al., 2011 ; Stallworth, 2010 ), and 3 articles examined teachers’ perspectives on YA literature and its significance in the English classroom ( Gibbons, Dail, & Stallworth, 2006 ; Glenn, King, Heintz, Klapatch, & Berg, 2009 ).

A second subcategory within engagement focused on choice and motivation for reading . In 2006 and in 2007, 2 articles explored books that are considered controversial and why adolescents read those books ( Enriquez, 2006 ; Sacco, 2007 ). Eight articles addressed how students become actively engaged in the literature; they also discussed how to present literature in ways that are appealing ( Bodart, 2010 ; Frey, Fisher, & Moore, 2009 ; Holbrook & Holbrook, 2010 ; Martinez & Harmon, 2011 ; Tuccillo & Williams, 2005; Weiss, 2007 ).

A third subcategory described the ways in which students could respond to literature instruction . This included 2 articles about how students could use art to respond to YA literature ( Baer, 2007 ; Bleeker & Bleeker, 2005 ) and 6 articles about how technology was being used as a forum for students to present their ideas about YA literature ( Hathaway, 2011 ) or to represent their interpretations of YA literature ( Davila, 2010 ). Finally, there were articles that highlighted the connections between films, music, and YA literature ( Brown, 2005 ; Seglem, 2006 ; Sitomer, 2008 ).

A fourth and final subcategory focused on instruction outside of the traditional classroom . Four articles spanning 2005–2010 examined the YA literature in libraries ( Arnold, 2005 ; Bowen & Tuccillo, 2006, Mac- Rae, 2007 ; Tuccillo, Goodman, Pompa, & Arrowsmith, 2007 ; Welch, 2010 ). Additionally, Salvner ( 2011 ) wrote an article featuring the Youngstown State University literature conference that gives students opportunities to read and discuss YA literature, to meet YA authors, and to engage in writing activities.

Forms, Formats, and Genres

The field of young adult literature is continually changing, shifting, and growing. This is most recognizable when one begins to consider the explosion of new forms and formats over the past 15 years ( Carter, 2008 ; Fletcher–Spear, Jenson–Benjamin, & Copeland, 2005 ). Rather than maintaining traditional print forms, YA literature has expanded to visual and media forms and formats. The influence of the arts, technology, and media has produced a constantly changing field—one in which authors, teachers, and researchers can defy classifications and restrictions of the term “genre.” This category boasts 31 articles (13.5%) written about the many forms, formats, and genres prevalent in the field of YA literature.

Although in 2005, authors were still examining more “traditional” genres, such as memoirs ( Marler, 2005 ; Rogers, 2005 ) and historical fiction ( Glenn, 2005 ), there began a trend to examine new genres, forms, and formats. Most notably, there was the immense popularity of graphic novels, which led to 7 articles from 2005–2011. Discussion focused on everything from their literary merit to defining graphic novels to promoting the benefits of the use of graphic novels in the classroom ( Carter, 2008 ; Fletcher–Spear, Jenson–Benjamin, & Copeland, 2005 ). Authors used the space to point out that using the term “genre” to classify graphic novels was restrictive. Instead, they argued that graphic novels are forms or formats, which include a variety of genres and topics.

While graphic novels seemed to have paved the way for the discussion about new formats of books, they do not represent the only shift in forms. In 2009, larger discussions in TAR began revolving around new formats and the influence of technology. Three articles explored books with new formats, such as free verse ( Cadden, 2011 ); books written in blended, multiple formats, such as blogs ( Olthouse, 2010 ); and intertextuality in books ( Hathaway, 2009 ). Similarly, beginning in 2009, 6 articles were written about digital advances and YA literature. These articles included conversations about video games ( Gerber, 2009 ), documentary films ( Phillips & Teasley, 2010 ), and digital communication ( Koss & Tucker, 2010 ). Authors used TAR articles to demonstrate how technology has allowed young adults to be producers and publishers of YA literature as evidenced by the rise of fan fiction ( Mathew & Adams, 2009 ).

Despite these relatively “new” formats, 2009–2011 was also a popular time for traditional genres—such as fantasy, science fiction, and folktales—to be examined under the guise of how gender ( Keeling & Sprague, 2009 ) and race ( Hood, 2009 ) might influence the literature. And 1 article examined the increasing popularity of street literature ( Brooks & Savage, 2009 ).

Important People

This category recognizes the authors of YA literature and those educators who have significantly contributed to the field of YA literature. With 64 articles (27.9%), this is the largest category. The people featured in this section moved the field of YA literature forward and were advocates for both YA literature and young adults.

The ALAN Review includes interviews with authors and features about authors. These articles examine authors whose work has made significant contributions to the field of YA literature. From 2005–2011, 25 interviews were conducted with YA authors. These interviews provide glimpses into the authors’ writing lives, their inspiration for their novels, and their interactions with their young adult readers. While they might write a variety of genres, the majority of authors interviewed were known primarily for their fiction. For example, High ( 2010 ) interviewed Laurie Halse Anderson, who is well known for her fiction (e.g., Speak, Wintergirls, and Twisted ) but also writes nonfiction for younger readers (e.g., Independent Dames ).

The ALAN Review also included author feature articles written about authors and their work. From 2005–2011, 15 articles explored YA authors, including analyses of their work. Similar to the subcategory of interviews , this subcategory seemed to be primarily dedicated to authors of fiction. For example, Walter Dean Myers has written over 50 fiction and nonfiction books, but he has been a National Book Award Finalist for his fiction books (e.g., Monster, Autobiography of My Dead Brother, and Lockdown ). This category also includes one short story by Crowe ( 2008 ).

The Important People category also contained 6 articles that were adapted Keynote speeches and workshops from the ALAN conference and 10 articles that recognize people in the field who have won awards or done significant work as professionals, teacher educators, and publishers. Finally, since 2005, the field of YA literature, and literature in general, have unfortunately lost significant members of the community, such as Ted Hipple, Janet McDonald, Louise Rosenblatt, Paula Danziger, and J. D. Salinger. TAR honored these people and their legacies through 8 articles and retrospective pieces. These articles shared their lives, how they influenced YA literature and how they shaped the field.

Significance

The 18 articles in this category (7.9%) explored the merits of YA literature, its significance in the literary community, and why it should be read and studied in the English language arts classroom. Although many articles featured in TAR included a rationale for why YA literature should be read, discussed, and valued, the main goal of these articles was to highlight the importance of YA literature. These authors provided overviews of the field and specifically arguments for the merits of YA literature.

From 2007 through 2011, 4 articles highlighted the importance of YA literature by analyzing books, topics, and trends. For example, in 2007, 2 articles ( Smith, 2007 ; Stephens, 2007 ) explored what was happening in the field of young adult literature. They examined the current trends and a sampling of books that highlight these trends. Similarly, in 2011, 2 articles provided a historical and contemporary look at the field, including the top books from 1999–2009 ( Glenn, 2011; Kaywell, 2011 ).

Also included in this category were 2 articles, published in 2005 and 2009, that argued for recognition of the “literary merit” of YA literature. For example, Soter and Connors ( 2009 ) argued that YA literature was indeed “literature,” was relevant to adolescents’ lives, and has literary sophistication that should be recognized and valued. Two other articles published in 2010 and 2011 described authors’ passion for YA literature ( Kienholz, 2010 ; Weiss, 2011 ).

A third subcategory of significance focused on the benefits of adolescents reading YA literature. For instance, 2 articles ( Hazlett, Johnson, & Hayn, 2009 ; Sitomer, 2010 ) discussed why young adults are engaged and motivated to read YA literature and a rationale for why middle school and high school teachers should include YA literature in their curriculum.

A final topic included in this category was Jerry Kaplan’s multiple reviews of research projects (e.g., overviews of doctoral dissertations). These reviews highlighted the important research that pushed the field of YA literature forward.

Theory

One of the smallest categories represented (4%) in The ALAN Review contained articles using literary theories to analyze YA literature. Authors of these articles used a theoretical lens to examine a book. For instance, Daniels ( 2006 ) provided an overview of different literary theories and books that could be examined using these theories. He argued that the use of literary theories would help break barriers between the YA literature community and the broader literary community. While Daniels’ ( 2006 ) work provided overviews of multiple theories, other authors analyzed novels through the specific lens of postmodernism ( Bleeker & Bleeker, 2008 ; Nicosia, 2008 ) and through a feminist and gender lens ( Tighe, 2005 ; Cobb, 2007 ).

From 2005–2011, 4 articles used other literary movements, theories from other fields, and other pieces of literature to provide a closer analysis of YA literature. For example, 1 article ( Redford, 2006 ) used transcendentalism to analyze Whiligig (Fleischman, 1999) and Stargirl (Spinelli, 2000). O’Sullivan ( 2005 ) used the work of developmental theorists such as Piaget and Kohlberg to explore depictions of evil in Lois Lowry’s Messenger . Similarly, the Harry Potter series is the subject of an article ( Garza, 2011 ) that explore how the books have various references to Biblical, Greek, and mythological literature.

The final 2 articles in this category explored instruction, but they were placed in this category because they were about teaching young adults literary theories such as Marxism ( Scherff, Lewis, & Wright, 2007 ) and critical theory ( Groenke & Maples, 2008 ). The goal of these articles was to examine the theoretical lens used to teach YA literature. These articles explored how young adults could learn about a specific theory and use it to facilitate a deeper understanding of the text.

Implications

We suggested that a closer examination of seven years of The ALAN Review articles would provide an opportunity to review past scholarship and consider new directions. Arguably, the choice of a seven–year time frame may seem arbitrary. Our choice was based on the year we began to pay closer attention to potential themes and trends in TAR ; we paused in 2012 to provide this snapshot in response to Glenn’s presidential observations. We hope that this analysis provides both immediate perspective as well as a baseline for those who wish to look further back or repeat this examination in the future.

A review of the past has clearly demonstrated that the field of YA literature has made exemplary efforts to be advocates for young adults and the literature close to their lives. It has also provided evidence of authors’ willingness to push against the norms and write about the topics alive and well amidst the angst of youth . Finally, this review has provided evidence supporting Glenn’s ( 2011 ) claim that YA authors and those from the field find ways to speak out for the marginalized and the underrepresented. In doing so, they have created a voice and space for young adults and the literature they read.

We acknowledge that this review is not an objective view of the field of YA literature or the scholarly work surrounding YA literature. There are many factors that influence what is published in The ALAN Review: from what ALAN’s members and TAR ’s writers find important enough to write about, to what the field as a whole—including the editors and reviewers— feel is significant enough to publish in The ALAN Review . This work, however, does provide a snapshot of the recent trends in the scholarship of YA literature.

Such a review has thus provided a look at past work, but it also provides implications for moving forward. As a community and as advocates of YA literature, we must ask ourselves if this represents what we believe about young adults and YA literature. Is this is the work we want to continue pursuing? Or are there new avenues and areas in the field to explore and discuss? There are at least eight implications that might both paint a picture of the future and provide opportunities for those in YA literature to shape that future.

1. Our work can provide complete opportunities to help young adults reflect on their lived experiences. Articles that fell in the category of adolescent lives highlighted young adults’ sexual identities as important to who adolescents are and how they are represented in YA literature. However, media–highlighted issues like body image or bullying were left relatively unaddressed in the pages of TAR during 2005–2011. Advocates for youth can continue to examine literature that provides opportunities to reflect on the lived experiences of our youth. This requires us to make sure young adults’ voices and experiences are not only heard, but also respected. We have to be advocates not only for the literature they read, but for the lives they live. It is our responsibility to ensure that when we, as adults, analyze YA literature, we make certain young adults’ lives are properly represented in the literature and that the literature is not creating stereotypes of who young adults might be.

2. Our work can provide opportunities for all young adults. The terms “young adults” or “adolescents” encompass an enormous range of young people from different races, ethnicities, classes, spiritualities, sexual preferences, family structures, and unique worlds. Articles published in the category of diversity demonstrated TAR ’s commitment to representing the diverse range of young adult readers; however, the small number of such articles suggests the need for more in–depth examinations of literature with this focus. The small number might also suggest that, as some of the authors point out, there is not an abundance of YA literature written about these diverse perspectives ( Loh, 2006 ). This might mean that the field needs both more YA literature encompassing diverse cultures and also more conversations about these books.

3. Our work can provide opportunities for examining reading in multiple contexts . The category of engagement offered evidence of TAR’s historical recognition of teachers, librarians, and the ways in which young adults interact with YA literature. For instance, the inclusion of Stories from the Field (first featured in the Fall of 2009) gave teachers and librarians space to share vignettes of experiences with young adult literature. Future work should continue to explore what it means to “teach” YA literature. How do we engage students in meaningful and powerful instruction? Future work should continue to explore preservice and inservice teachers’ experiences with YA literature and how their reading might push them to consider their interactions with young adults.

While there was scholarship surrounding YA literature in classrooms, there were very few articles published in this time frame that focused on reading YA literature in out–of–school contexts. The classroom is an important space—but not the only space—in which to utilize YA literature. Future articles could help promote the field by focusing on context. We should continue to explore the other spaces where young adults are engaged in reading and discussing YA literature.

4. Our work can provide research and teaching forays into new forms of YA literature . While we cannot dismiss the “traditional” print genres, the form category demonstrated the potential influence of technological advances and multimodality literacies on the field of YA literature. Technology is changing how authors are creating YA literature. And technology will continue to change how we view literature, providing new opportunities for delivery, interaction, and response. Authors, teachers, and researchers can help guide how students get access to material and how they move from consumers to producers. What will YA literature “look like” in 5, 10, or 15 years? What does this change in form and formats mean for the scholarship surrounding the field? How do the changes in form and format influence the theoretical work that has explored how readers make meaning from text?

5. Our work can provide access to new, diverse authors representing multiple genres . The author interviews and features provided the field with an understanding of authors and educators who have demonstrated their passion and commitment to the field of young adult literature. A majority of the authors did work in fiction; additionally, there was a significant decrease in such publications in the last few years, which may be due to the change in the editorial team. Increased work in this area would not only draw attention to important writers but also to new genres and new forms of writing.

6. Our work can promote the value of YA literature. Many of the articles in the significance category noted that YA literature has been historically undervalued in our field. More articles and continued research could provide insight into just why YA literature is so important. We should ask ourselves how we can determine the value of YA literature and what research methodologies might best be used to answer such questions. As a community that represents YA literature, we must also ask ourselves what are the ways we continue to promote the scholarship of YA literature? What should we be doing to make sure that YA literature and the scholarship surrounding YA literature are valued?

7. Our work can guide theory development and use. The theory category featured articles that used theories inside and outside of the field to explore the craftsmanship of YA literature. In addition to research on significance, articles that use literary theory or develop theory will also continue to promote the legitimacy of YA literature in the broader literary community.

8. There is value in using multiple data points in examining and reexamining the direction of our work. The previous seven implications have focused on the “so–what” of the content analysis of the articles published from 2005–2011. Those implications can be directly tied to the themes or categories that emerged from the longitudinal analysis. However, there will no doubt be readers who spend more time reflecting on the quantitative data available in Table 1. They will ask questions about why some categories did not appear or why other categories seemed to take such a leading role (e.g., Important People with 27.9%). A final implication of this work is the reminder of the importance of not just using data, but of using multiple points of data to inform our reflections.

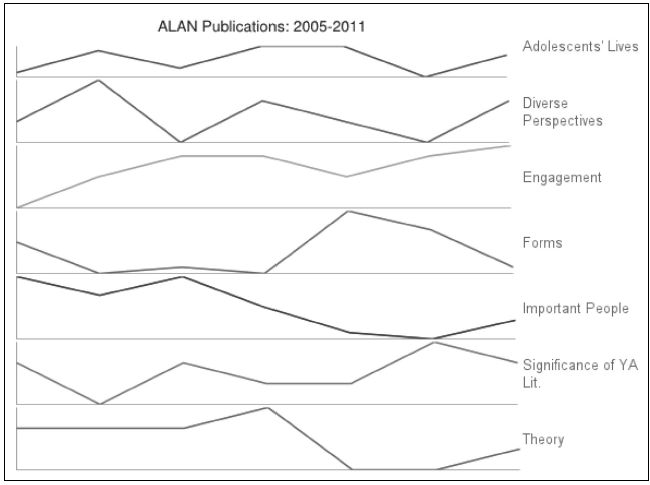

Figure 1 visually highlights the same information found in Table 1. However, instead of representing simple percentages that might be found in a pie chart, Figure 1 highlights the number of contributions over the longitudinal scope of this article. We begin to see interesting trends with this perspective. Note, for instance, the relative growth over time of Engagement and Significance articles compared to the relative decline of Important People and Theory . See also the frequent return to issues of diversity. There are probably historical answers tied to these data trends, such as special issues of The ALAN Review . The point is that emerging themes can tell us how our work (as evidenced by publications in The ALAN Review ) is attempting to influence the field. It can also show us the kinds of areas on which we have focused or failed to focus. In the end, it also reminds us that using multiple tools can help us reexamine when things were important and when they might need to be brought back to the surface. Examining the data in multiple ways can help us show how much research we have as well as how scholarship has changed over time.

Figure 1.

Conclusion

The eight implications highlighted in this article reflect a changing world that will continue to evolve independent of the works of those who advocate for youth and for YA literature. Said differently, technology continues to change how we get access to literature and how we engage with that text. Changes in world economies, health, and culture impact the angst experienced by our youth. And many fields argue for the value they have in engaging youth in these areas. Therefore, although our past has been fruitful, and indicators suggest we are indeed ready to stand the winds of change, these implications will not happen automatically. We have an opportunity to shape the field and to shape the lives of our youth using that which we value so much—YA literature.

Kristine E. Pytash is an assistant professor in literacy education at Kent State University. She co–directs the secondary Integrated Language Arts teacher preparation program.

Rick Ferdig is the Summit Professor of Learning Technologies and Professor of Instructional Technology at Kent State University. He works within the Research Center for Educational Technology and also the School of Lifespan Development and Educational Sciences.

References

Adomat, D. (2009). Issues of physical disabilities in Cynthia Voigt’s Izzy, Willy–Nilly , and Chris Crutcher’s The crazy horse electric game . The ALAN Review, 36(2), 40–47.

Arnold, M. (2005). Get real! @ your library—teen read week. The ALAN Review, 33 (1), 14–6.

Baer, A. L. (2007). Constructing meaning through visual spatial activities: An ALAN grant research project. The ALAN Review, 34 (3), 21–29.

Baer, A. (2011). Diversions: Finding space to talk about young adult literature in a juvenile home. The ALAN Review, 38 (3), 6–13.

Bannon, A. (2008). Teaching they poured fire on us from the sky: An opportunity for educating about displacement and genocide. The ALAN Review, 36 (1), 80–84.

Bean, T. W. (2008). The localization of young adult fiction in contemporary Hawai`i. The ALAN Review, 35 (2), 27–35.

Bell, K. (2011). “A family from a continent of I don’t know what”: Ways of belonging in coming–of–age novels for young adults. The ALAN Review, 38 (2), 23–31.

Bickmore, S. T. (2005). Language at the heart of the matter: Symbolic language and ideology in the heart of a chief. The ALAN Review, 32 (3), 12–23.

Bittel, H. (2009). From basketball to Barney: Teen fatherhood, didacticism, and the literacy in YA fiction. The ALAN Review, 36(2) , 94–99.

Blackford, H. (2005). The wandering womb at home in The red tent: An adolescent bildungsroman in a different voice. The ALAN Review, 32 (2), 74–85.

Bleeker, G. W., & Bleeker, B. (2005). Hearts and wings: Using young adult multicultural poetry inspired by art as models for middle school artists/writers. The ALAN Review, 33 (1), 45–49.

Bleeker, G. W., & Bleeker, B. S. (2008). Literary landscapes: Using young adult literature to foster a sense of place and self. The ALAN Review, 35 (2), 84–90.

Bloem, P. (2011). Humanizing the “so–called enemy”: Teaching the poetry of Naomi Shihab Nye . The ALAN Review, 38 (2), 6–12.

Bodart, J. (2010). Booktalking: That was then and this is now. The ALAN Review, 38 (1), 57–63.

Bott, C. J., Garden, N., Jones, P., & Peters, J. A. (2007). Don’t look and it will go away: YA books—a key to uncovering the invisible problem of bullying. The ALAN Review, 34 (2), 44–51.

Bowen, L., & Tuccillo, D. (2006). Attracting, addressing, and amusing the teen reader. The ALAN Review, 34 (1), 17–24.

Brown, J. E. (2005). Film in the classroom: The non–print connection. The ALAN Review, 32 (2), 67–73.

Brooks, W., & Savage, L. (2009). Critiques and controversies of street literature: A formidable literary game. The ALAN Review, 36 (2), 48–55.

Cadden, M. (2011). The verse novel and the question of genre. The ALAN Review, 39 (1), 21–27.

Caillouet, R. (2005). The adolescent war: Finding our way on the battlefield. The ALAN Review, 33 (1), 68–73.

Carter, J. B. (2008). Die a graphic death: Revisiting the death of genre with graphic novels, or “why won’t you just die already?” The ALAN Review, 36 (1), 15–25.

Cobb, C. D. (2007). The day that daddy’s baby girl is forced to grow up: The development of adolescent female subjectivity in Mildred D. Taylor’s The gold cadillac. The ALAN Review, 34 (3), 67–76.

Crandall, B. R. (2009). Adding a disability perspective when reading adolescent literature: Sherman Alexie’s The absolutely true diary of a part–time Indian . The ALAN Review, 36 (2), 71–78.

Crowe, C. (2008). Fahrenheit 113. The ALAN Review, 36 (1), 50–54.

Cummins, A. (2011). Beyond a good/bad binary: The representation of teachers in contemporary YAL. The ALAN Review, 39 (1), 37–45.

Daniels, C. L. (2006). Literary theory and young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 33 (2), 78–82.

Davila, D. (2010). Not so innocent: Book trailers as promotional text and anticipatory stories. The ALAN Review, 38 (1), 32–42.

Enriquez, G. (2006). The reader speaks out: Adolescent reflections about controversial young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 33 (2), 16–23.

Fletcher–Spear, K., Jenson–Benjamin. M., & Copeland, T. (2005). The truth about graphic novels: A format, not a genre. The ALAN Review, 32 (2), 37–44.

Franzak, J. K. (2009). Social upheaval and psychological scarring: Exploring the future in Meg Rosoff’s How I live now . The ALAN Review, 36 (2), 34–39.

Frey, N., Fisher, D., & Moore, K. (2009). Literacy letters: Comparative literatue and formative assessment. The ALAN Review, 36 (2), 27–33.

Garza, D. (2011). Harry Potter and the enchantments of literature. The ALAN Review, 38 (1), 64–68.

Gerber, H. (2009). From the FPS to the RPG: Using video games to encourage reading YAL. The ALAN Review, 36 (3), 87–91.

Gibbons, L. C., Dail, J. S., & Stallworth, B. J. (2006). Young adult literature in the English curriculum today: Classroom teachers speak out. The ALAN Review, 33 (3), 53–61.

Glenn, W. (2005). History flows beneath the fiction: Two roads chosen in redemption and a northern light. The ALAN Review, 32 (3), 52–58.

Glenn, W. (2006). Boys finding first love: Soul–searching in the center of the world and swimming in the monsoon sea. The ALAN Review, 33 (3), 70–75.

Glenn, W. J., King, D., Heintz, K., Klapatch, J., & Berg, E. (2009). Finding space and place for young adult literature: Lessons from four first–year teachers engaging in out–of–school professional induction. The ALAN Review, 36 (2), 6–17.

Glenn, W. (2011). Flash back—forge ahead: Dynamism and transformation in young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 39 (1), 7–11.

Gold, E., Caillouet, R., & Fick, T. (2007). Teaching (w)holes: Wordplay and reversals in Louis Sachar’s Holes . The ALAN Review, 34 (3), 46–52.

Gold, E., Caillouet, R., Holland, B., & Fick, T. (2009). Recovery of self and family in Sharon Creech’s The wanderer: Literature as equipment for living. The ALAN Review, 36 (3), 6–12.

Greinke, R. (2007). “Art is not a mirror to reflect reality, but a hammer to shape it”: How the changing lives through literature program for juvenile offenders uses young adult novels to guide troubled teens. The ALAN Review, 34 (3), 15–20.

Groenke, S. L., & Maples, J. (2008). Critical literacy in cyberspace? The ALAN Review, 36 (1), 6–14.

Hallman, H. (2009). Novel roles for books: Promoting the use of young adult literature with students at a school for pregnant and parenting teens. The ALAN Review, 36 (2), 18–26.

Hathaway, R. V. (2009). “More than meets the eye”: Transformative intertextuality in Gene Luen Yang’s American born Chinese . The ALAN Review, 37 (1), 41–47.

Hathaway, R. (2011). A powerful pairing: The literature circle and the wiki. The ALAN Review, 38 (3), 14–22.

Hauschildt, P. M. (2006). Worlds of terrorism: Learning through young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 33 (3), 18–25.

Hayn, J., & Hazlett, L. (2008). Connecting LGBTQ to others through problem novels: When a LGBTQ is not the main character. The ALAN Review, 36 (1), 66–72.

Hazlett, L. A., Johnson, A., & Hayn, J. A. (2009). An almost young adult literature study. The ALAN Review, 37 (1), 48–58.

High, L. (2010). Cracks of light in the darkness: Images of hope in the work of Laurie Halse Anderson and an interview with the author. The ALAN Review, 38 (1), 64–71.

Holbrook, T., & Holbrook, H. (2010). Pushing back the shadows of reading: A mother and daughter talk of YA novels. The ALAN Review, 37 (2), 49–53.

Hood, Y. (2009). Rac(e)ing into the future: Looking at race in recent science fiction and fantasy novels for young adults by black authors. The ALAN Review, 36 (3), 81–86.

Insenga, A. (2011). Goth girl reading: Interpreting identity. The ALAN Review, 38 (2), 43–49.

Jeffery, D. (2009). Reading reluctant readers (aka books for boys). The ALAN Review, 36 (2), 56–63.

Jones, P. (2006). Stargirls, stray dogs, freaks, and nails: Person vs. society conflicts and nonconformist protagonists in young adult fiction. The ALAN Review, 33 (3), 13–17.

Kahn, S., & Wachholz, P. (2006). Rough flight: Boys fleeing the feminine in young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 34 (1), 66–73.

Kaywell, J. (2011). The top young adult books from this decade: 1999–2009. The ALAN Review, 38 (3), 73–77.

Kaywell, J. F., Kelley, P. K., Edge, C., McCoy, L., & Steinberg, N. (2006). Growing up female around the globe with young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 33 (3), 62–69.

Keeling, K. K., & Sprague, M. M. (2009). Dragon–slayer vs. dragon–sayer: Reimagining the female fantasy heroine. The ALAN Review, 36 (3), 13–17.

Kienholz, K. (2010). Island hopping: From The cay to Treasure island to Lord of the flies to The tempest . . . and back again. The ALAN Review, 38 (1), 53–56.

Koss, M., & Tucker, R. (2010). Representations of digital communication in young adult literature: Science fiction as social commentary. The ALAN Review, 38 (1), 43–52.

Kuo, N. H., & Alsup, J. (2010). “Why do Chinese people have weird names?”: The challenges of teaching multicultural young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 37 (2), 17–24.

Lautenbach, C. (2007). Follow the leaders in Newbery tales . The ALAN Review, 34 (2), 68–88.

Loh, V. (2006). Quantity and quality: The need for culturally authentic trade books in Asian–American young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 34 (1), 44–62.

MacRae, C. D. (2007). Teachers and librarians working together for teens and their reading. The ALAN Review, 34 (2), 6–12.

Madill, L. (2008). Gendered identities explored: The lord of the rings as a text of alternative ways of being. The ALAN Review, 35 (2), 43–49.

Marler, M. D. (2005). Memoirs of survival: Reading the past and writing it down. The ALAN Review, 32 (2), 86–91.

Martinez, M., & Harmon, G. (2011). An investigation of student preferences of text formats. The ALAN Review, 39 (1), 12–20.

Mathew, K. L., & Adams, D. C. (2009). I love your book, but I love my version more: Fanfiction in the language arts classroom. The ALAN Review, 36 (3), 35–41.

Medina, C. L. (2006). Interpreting Latino/a literature as critical fictions. The ALAN Review, 33 (2), 71–77.

Menchetti, B., Plattos, G., & Carroll, P. S. (2011). The impact of fiction on perceptions of disability. The ALAN Review, 39 (1), 56–66.

Metzger, K., & Kelleher, W. (2008). The dearth of native voices in young adult literature: A call for more young adult literature by and for indigenous peoples. The ALAN Review, 35 (2), 36–42.

Miller, S. J., & Slifkin, J. M. (2010). “Similar literary quality”: Demystifying the AP English literature and composition open question. The ALAN Review, 37 (2),6–16.

Miskin, K. (2011). YA literature in translation: A batch of Batchelder honorees. The ALAN Review, 39 (1), 67–75.

Nicosia, L. (2008). Louis Sachar’s Holes : Palimpsestic use of the fairy tale to privilege the reader. The ALAN Review, 35 (3), 24–29.

Olthouse, J. (2010). Blended books: An emerging genre blends online and traditional formats. The ALAN Review, 37 (3), 31–37.

O’ Sullivan, S. (2005). Depictions of evil in Lois Lowry’s Messenger . The ALAN Review, 33 (1), 62–67.

O’Quinn, E. J. (2008). “Where the girls are”: Resource and research. The ALAN Review, 35 (3), 8–14.

O’Quinn, E. J., & Atwell, H. (2010). Familiar aliens: Science fiction as social commentary. The ALAN Review, 37 (3), 45–50.

Pajka–West, S. (2007). Perceptions of deaf characters in adolescent literature. The ALAN Review, 34 (3), 39–45.

Phillips, N. (2005). Can “you” help me understand? The ALAN Review, 33</span>(1), 23–29.

Phillips, N., & Teasley, A. (2010). Reading reel nonfiction: Documentary films for young adults. The ALAN Review, 27 (3), 51–59.

Quick, C. S. (2008). “Meant to be huge”: Obesity and body image in young adult novels. The ALAN Review, 35 (2), 54–61.

Redford, S. (2006). Transcending the group, discovering both self and public spirit: Paul Fleischman’s Whiligig and Jerry Spinelli’s Stargirl . The ALAN Review, 33 (2), 83–87.

Robillard, C. (2009). Hopelessly devoted: What Twilight reveals about love and obsession. The ALAN Review, 37 (1), 12–17.

Rogers, T. (2005). Writing back: Rereading adolescent girlhoods through women’s memoir. The ALAN Review, 33 (1), 17–22.

Sacco, M. T. (2007). Defending books: A title index. The ALAN Review, 34 (2), 89–103.

Saldaña Jr., R. (2012). Mexican American YA lit: It’s literature with a capital ‘L’! The ALAN Review, 39 (2), 68–73.

Salvner, G. (2011). Outside the classroom: Celebrating YA lit at the English festival. The ALAN Review, 38 (3), 37–42.

Scherff, L., & Lewis Wright, C. (2007). Getting beyond the cuss words: Using Marxism and binary opposition to teach Ironman and Catcher in the rye . The ALAN Review, 35 (1), 51–61.

Scherif, L., Arteta–Durini, I., McGartlin, C., Stults, K., Welsh, E., & White, C. (2008). Teaching memoir in English class: Taking students to Jesus land . The ALAN Review, 35 (3), 69–78.

Seglem, R. (2006). YA lit, music, and movies: Creating reel interest in the language arts classroom. The ALAN Review, 33 (3), 76–80.

Sitomer, A. L. (2008). Yo, hip–hop’s got roots. The ALAN Review, 35 (2), 24–26.

Sitomer, A. (2010). Scattering light over the shadow of booklessness. The ALAN Review, 37 (2), 44–48.

Smith, S. (2007). The death of genre: Why the best YA fiction often defies classification. The ALAN Review, 35 (1), 43–50.

Smith, K. A. (2009). Roses are red. The ALAN Review, 36 (2), 79–88.

Soter, A. O., & Connors, S. P. (2009). Beyond relevance to literary merit: Young adult literature as “literature.” The ALAN Review, 37 (1), 62–67.

Sprague, M. M., Keeling, K. K., & Lawrence, P. (2006). “Today I am going to meet a boy”: Teachers and students respond to Fifteen and Speak . The ALAN Review, 34 (1), 25–34.

Stallworth, J. (2010). Preservice teachers’ suggestions for summer reading. The ALAN Review, 38 (1), 23–31.

Stephens, J. (2007). Young adult: A book by any other name . . . : Defining the genre. The ALAN Review, 35 (1), 34–42.

Tighe, M. A. (2005). Reviving Ophelia with young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 33 (1), 56–61.

Thomas, E. (2011). Landscapes of city and self: Place and identity in urban young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 38 (2), 13–22.

Town, C. J. (2006). ‘Join and escalate’: Chris Crutcher’s coaches. The ALAN Review, 33 (2), 65–70.

Tuccillo, D., & Williams, L. (2005). Summer reading—magic! The ALAN Review, 33 (1), 30–36.

Tuccillo, D. P. (2006). Quiet voices with a big message. The ALAN Review, 33 (2), 34–42.

Tuccillo, D., Goodman, P., Pompa, J., & Arrowsmith, J. (2007). Spontaneous combustion: School libraries providing the spark to connect teens, books, reading—and even writing! The ALAN Review, 35 (1), 62–66.

Vasquez, A. (2009). Breathing underwater: At–risk ninth graders dive into literary analysis. The ALAN Review, 37 (1), 18–28.

Vincent, Z. (2008). The tiny key: Unlocking the father/child relationship in young adult literature. The ALAN Review, 35 (3), 36–44.

Weiss, M. J. (2007). Important resources! The ALAN Review, 34 (3), 77–80.

Weiss, M. J. (2011). Is the sky really falling? The ALAN Review, 38 (2), 58–60.

Welch, C. C. (2010). Dare to disturb the universe: Pushing YA books and library services with a mimeograph machine. The ALAN Review, 37 (2), 59–64.

Westenskow, N. (2009). Expanding world views: Young adult literature of New Zealand. The ALAN Review, 37 (1), 35–40.

White–Kaulaity, M. (2006). The voices of power and the power of voices: Teaching with Native American literature. The ALAN Review, 34 (1), 8–16.

Zitlow, C., & Stove, L. (2011). Portrait of the artist as a young adult: Who is the real me? The ALAN Review, 38 (2), 32–42.