ALAN v42n3 - T35 Using Graphic Memoirs to Discuss Social Justice Issues in the Secondary Classroom

T35 Using Graphic Memoirs to Discuss Social Justice Issues in the Secondary Classroom

Traditionally, comics and graphic novels have been perceived as “kids’ stuff” appropriate only for pleasure reading. However, I believe this perception is outdated. Over time, graphic narratives that pertain to war and other historically significant issues have made their way into classroom settings. With their combination of words and pictures, graphic narratives with social justice stories are conducive to teaching critical literacy skills. In particular, Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman (1986) , Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White by Lila Quintero Weaver (2012) , and A Game for Swallows by Zeina Abirached (2007) are graphic memoirs that depict messages of social justice and identity pertinent to young adults.

Pictures, especially those in stories with social justice themes, can aid readers because visuals can bring candor to situations that might otherwise be too difficult to tell and too harsh for a less experienced adolescent mind to comprehend. For instance, images depicting violence proclaim themselves as representations rather than reality by their very nature, thus providing the necessary critical distance to make the subject matter more bearable. These images capitalize on the techniques of drawing and art to call upon readers’ own visual memories of actual experiences. Hunt (2008) supports this stance by pointing out that the picturebook form, including the graphic medium, “lends itself well to memoir, dystopia, and wordless narrative” because the writer can use both words and pictures to tell his or her life story (p. 425) . By advocating for these specific texts, I hope to raise awareness of the comics/graphica medium as an effective teaching tool, particularly for social justice and critical literacy.

To reveal more saliently the unique benefits of the graphic form in the teaching of social justice, this study utilizes the critical literacy theories of Janks (2000) , Behrman (2006) , and Lewison, Flint, and Van Sluys (2002) , foundational scholars of critical literacy. Critical literacy practices can reinforce literary analysis and encourage students to turn new understandings into positive actions. In this article, I discuss critical literacy in the context of the three novels above and explain how they can be used in the classroom to explore issues of identity and social justice, both of which are important to adolescents. Within these novel discussions, I offer examination of key themes and suggestions for use of these graphic novels for critical literacy discussions, interdisciplinary teaching, and writing. Further, in the Appendices to this article, I provide a list of additional graphic novels and academic resources, as well as charts explaining critical literacy’s relationship to the Common Core State Standards (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010) as resources for teachers and teacher educators.

Justification for Multicultural Graphic Memoirs

To better understand the graphic novel form, it is important to define the comic medium and differentiate between graphic novels and comic books. Will Eisner, the famous comic artist and one of the founding writers of graphic novels, defines comics as “sequential art” (McCloud, 1993, p. 5) . Cary (2004) extends this definition by citing the framing offered by The World Encyclopedia of Comics , which defines comics as “a narrative form containing texts and pictures arranged in sequential order” (p. 11) . Comic is an umbrella term, and comic books and graphic novels have slightly different definitions under this umbrella. Their text and picture style are the same, but their serialization is different. Thompson (2008) reminds us that comic books “tend to carry the story line from one month to the next—often monthly” (p.9) . Graphic novels “follow a format similar to that of comic books but differ in that they tend to have full length story lines, meaning that the story starts and ends within the same book” (p. 9) . It is important to acknowledge that comics and graphic novels are a form rather than a genre, as they both have stories that can, on different occasions, affiliate with many possible genres, including superhero, mystery, fantasy, and nonfiction, among others (Carter, 2008) . Both comics and graphic novels can vary in subject matter. In his article for The English Journal , Letcher (2008) defines the graphic novel very specifically as “any book-length narrative comprised of sequential art, or more simply, an entire book written and illustrated in the style of a comic book” (p. 93) . The stories of graphic novels are meant to stand alone, unless of course they have sequels. Comics, in contrast, tend to be serialized.

The comics/graphica medium is conducive to telling stories of marginalization and oppression. Since comics faced a certain amount of criticism early on for being too simplistic, they have sometimes been thought of as a marginalized, or lower status, medium (Schwartz, 2010) . However, this status has given many artistic comic writers room to experiment with the medium and use the combination of visual images and words to tell true stories of the characters’ oppression. Some underground comics tackled such serious issues as oppression and minority rights in the 1960s, while Will Eisner’s 1978 publication of the graphic novel, A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories , brought this social justice theme more to the forefront (Schwartz, 2010) . Because comics have a history of telling stories of oppressed minorities, that history itself could be part of classroom instruction, including asking students to create a timeline of major graphic narratives focused on major historical issues.

In her important humanities work related to comics, Hillary Chute (2010) has noted that the graphic narrative style works well with such graphic autobiographies as The Complete Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (2007) because the comic form gives the reader access to both the reflective narrator’s voice and the child’s experiences. Additionally, Chute argues that the simplicity of comic drawings can make the traumatic scenes more palpable to the reader. That simplicity makes the characters in graphic narratives relatable by making it easier for the reader to insert himself or herself into the story. Adolescents in the United States, who are sometimes sheltered from the direct effects of war, can learn about war and other trauma from these graphic narratives.

Today, if we are teaching undergraduates or middle or high school students, we are teaching members of the millennial generation and younger, many of whom grew up with the Internet and are heavily engaged with social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter. As Whitlock and Poletti (2008) suggest in their article, “Self-Regarding Art,” some of the same interest that students of the new generation have in social media could transfer to graphic novels, particularly “autographics” that tell specific life stories. Graphic memoirs are similar to Facebook and Twitter because they “present narrative strategies reminiscent of adolescent behaviors and subcultures, such as experimentation with self-image, a heightened awareness of the potential for images to produce shock in the viewer, and a fascination with the power of social and visual performance in the construction of identity” (p. xviii) . Adolescents might be more likely to connect to books that are closely aligned with their media-based, fast-paced world and that deal with issues pertaining to self-identity. Particularly when dealing with such sensitive issues as social justice, it is important for us as teachers to choose texts that are engaging to our readers. Graphica forms provide this benefit.

To highlight potentially productive teaching strategies that capitalize on the power of the graphic narrative, I provide a close look at three specific texts for young adult readers. Darkroom (Weaver, 2012) offers a unique perspective; it is a memoir of an Argentinian American girl who grew up in Alabama in the 1960s and experienced the racism of the Jim Crow south. The narrator’s family had interactions with both White and Black people in the town, and the reader experiences the family’s somewhat emotionally distant view of segregation, given that this was not something they encountered in their home country.

A Game for Swallows (Abirached, 2007) portrays a religion-based war and an adolescent girl who holds on to her own identity in the midst of political strife. It is an international text by a Lebanese woman and translated from French into English. Its implementation in the classroom would add rich and unique diversity to the curriculum.

Maus I (Spiegelman, 1986) has gained attention from educators and scholars because it deals thoughtfully with sensitive historical issues related to Holocaust survivors. Revisiting the Holocaust through a survivor’s account as reinscribed by his cartoonist son, Art, Maus I explores the long-term impact of the concentration camps on those who eventually escaped them and the challenges that the descendants of survivors face when trying to provide comfort and understanding.

All three books depict social justice issues and advocate for equal rights for people of all races and creeds. Additionally, they depict minority characters and experiences in a respectful manner. They are based on historical events that involved oppression linked to race and/or religion and explore how the protagonists persevered despite the odds against them.

Critical Literacy and Critical Reading Lens

To help students better understand graphic memoirs that tell stories of oppression, educators should invoke reading approaches and activities based on critical literacy. According to Barbara Comber (2001) , critical literacies “involve people using language to exercise power, to enhance everyday life in schools and communities, and to question practices of privilege and injustice” (p. 1) . Critical reading , a practice common in high school English classes, encourages students to question and investigate sources, identify an author’s purpose, make inferences and judgments, separate fact from opinion, identify literary elements, and make predictions (Cervetti, Pardales, & Damico, 2001) . Critical literacy adds an additional step: praxis, or action, to improve the surrounding community.

Critical reading is a necessary step in the critical literacy process, but critical literacy asks that students go further to examine power relationships and social values as depicted in the text and determine how they can use the book’s lessons to promote change. As an example, a classroom exercise promoting a move from critical reading to critical literacy through Satrapi’s Persepolis could focus on a scene where the young female protagonist describes the veils that women in Tehran had to wear while she was growing up. Students might find examples in the book that depict women wearing veils and analyze the accompanying dialogue (critical reading). Students might then consider what these scenes say about gender roles and power dynamics in the book (critical literacy). These same interpretative and critical thinking practices transfer to other graphic memoirs and visual texts, allowing students to develop critical literacy skills.

According to Lewison, Flint, & Van Sluys (2002) , critical literacy has four main components: “disrupting the commonplace, interrogating multiple viewpoints, focusing on socio-political issues, and taking a stand and promoting social justice” (p. 382) . To be fully engaged in the critical literacy process, students need to participate in all four components. When teachers and students are first introduced to the critical literacy process, they may choose to be involved in only some elements of the process, but the long-term goal of critical literacy is for teachers to understand and implement the entire process into the classroom and, as a result, support students in their own comprehension of critical literacy (Lewison, Flint, & Van Sluys, 2002) .

To engage students in the critical literacy process, a teacher might pose thought-provoking questions about how a novel reflects power relationships in society. Questions about interpretation and author’s purpose are good initial steps, as they encourage critical reading skills, but critical literacy involves additionally asking how the text portrays relationships of social dominance and power (Cervetti, Pardales, & Damico, 2001) . If students can ask and answer thought-provoking questions about not only how the text relates to their own lives, but also how the text questions the status quo and power relationships in society, then they are engaging in critical literacy (Lewison, Flint, & Van Sluys, 2002) . Again, to use Persepolis as an example, when exploring scenes in the novel that show how Marji’s school is changed by the rise of the Islamic political structure, students engaging in critical literacy could point to specific visual details that connote oppression of secular lifestyles.

Hilary Janks (2000) identified four areas of critical literacy for potential consideration in the classroom. The domination strand questions how language contributes to the current structures of the status quo. As a parallel, the access perspective tries to provide more equal accessibility to the dominant language without compromising the nondominant forms. The diversity perspective focuses on how language shapes social identities. And the design perspective focuses on semiotic signs, as related to language and literacy. Behrman (2006) reminded us that to achieve critical literacy in the classroom, all four of these aspects must be addressed in a balanced manner. He suggested four primary activities for achieving this goal: reading supplementary texts, reading multiple texts, reading from a resistant perspective, and producing counter texts. The critical literacy discussion questions and activity suggestions I suggest throughout the article bear in mind the philosophies of Janks (2000) , Behrman (2006) , and Lewison, Flint & Van Sluys (2002) .

Analysis of Graphic Literature and Critical Literacy Questions

Maus I

by Art Spiegelman

I start the discussion with

Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale

by

Art Spiegelman

(1986)

because it is one of the betterknown

graphic novels for adolescents and, therefore,

a solid base from which to draw examples. Maus I

is a compelling autographic about Art, the son of a

Holocaust survivor, who describes how his father’s

World War II experiences affect both father and son.

The novel effectively employs symbolism as Vladek

narrates his lived experiences of the Holocaust to his

son, an artist and a writer. The most obvious scenes

involving symbolism and social justice center on the

interactions between the mice, or the Jewish people,

and the cats, or the Germans. The cat-as-predator and

mouse-as-prey dynamic invites discussion of power

relationships—an important conversation from a critical

literacy lens.

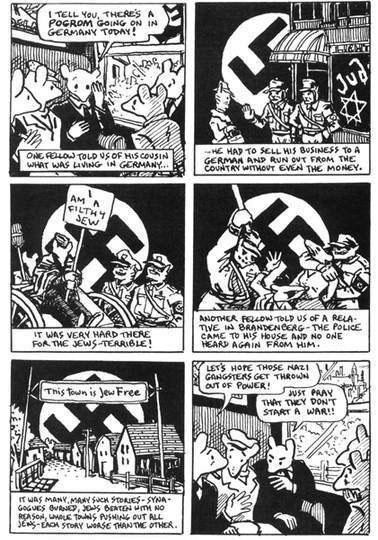

Page 33 of the book shows several vignette scenes where the cats beat the mice and force them out of their towns. Through the spoken words and images of the uniformed cats clubbing the mice, the reader interprets the German cats as the oppressors and the Jewish mice as the oppressed victims. The use of animals to employ symbolism gives the reader a visual of the hierarchy, drawing upon a “cat chasing the mouse” motif. Also, while the shading of the picture is dark, the mice are white, depicting a traditional contrast between light and dark, innocence and evil. The light and dark contrast serves as a key motif throughout the book as Vladek seeks to better understand the Holocaust and how the traumatic experiences have shaped him. Art, his son, seeks to know his father better and how his father’s trauma has affected his family and his life. Some of the visual cues in the book, such as Art’s and Vladek’s body language when they converse with one another, could create an intriguing dialogue about the nature of this father–son relationship through both visuals and words in graphic memoirs.

There are other scenes in Maus I where the images are more subtle but still important to notice. An example is the family dinner scene shown on page 74. On a surface level, everything appears to be fine. The family is having dinner and enjoying one another’s company. In that context, students could be invited to identify elements of the scene that resonate with their own favorite family meals. They might note such details as the way people dress, where people sit, and what people do when they are not eating, such as the boy who reads his book. The narrator’s father Vladek, pictured on the top left, comments that the Germans could not destroy everything at once.

However, at a closer glance, the reader will notice that the window very much resembles prison bars. Therefore, in spite of the closeness and sense of normality conveyed at the family table, the mice are still victims who will soon be imprisoned and oppressed. Additionally, through prompting, students will notice that the scene has a feeling of surveillance. The nicely dressed family enjoys dinner together, yet there is a sense that they are being watched. From a critical literacy stance, students can discuss how both the words and images contribute to the reading of this story and the irony of Vladek’s comments in contrast to the jarring image of entrapment. Some students will notice the picture symbolism right away, while others will need questions and prodding. In either case, graphic novels provide a strong avenue toward expanding critical literacy and literary interpretation skills to images and other multimodal texts.

Maus I is a novel that is conducive to cross-curricular studies related to critical literacy. In her description of her Maus I project, high school teacher Paige Cole (2013) explains that she chooses to teach Maus I in her high school social studies class because “it is just as much about Art as it is about Vladek. Spiegelman does a great job depicting the tension between his father’s discourse and his own” (p. 119) . Like many great works of young adult literature, Maus I is in part about the tension in a parent/child relationship, a dynamic that one can study under a critical literacy lens. Because of the theme of parent/child interaction, adolescents will relate to Art’s quest for self-identity through hearing his father’s stories about the Holocaust. The book is truly a story within a story.

Art inserts himself as a narrator of the outer story frame so he can share insights and observations of his father. In the inside story frame, Vladek narrates the events of the Holocaust, since he is the one who experienced them and can serve a witnessing role. Students could thus discuss whose story Maus I truly is and how the parent/child dynamic plays a role in how the story is told. To help them explore this theme as conveyed in the graphic medium, students might be asked to write a comic about their own family from their own voice and then again from a parental figure’s voice. Works such as Maus I lend themselves to a discussion of narrative voice and perspective.

In graphic novel workshops for both teachers and college students, I have shown the image of Maus I with the family eating dinner amid the barred windows as a vehicle for discussion and also as a writing prompt. Sometimes, before showing the Maus I images, I will have students view a political cartoon and write a response to the cartoon’s message. The images from both the political cartoon and the graphic memoir are good springboards for discussion of how comics can make political statements. Through pairing Maus I with political cartoons, students can have intriguing discussions in both English and social studies classes about power relations and the effect of war and other major social events on society. Depending on the grade level, teachers can either provide political cartoons or ask the students to find their own political cartoons related to current events, and then pinpoint how both the visuals and the words contribute to the cartoon’s statement.

The following can be a guide for discussing Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale (and possibly The Complete Maus , which also includes Maus II: My Father Bleeds History ) with a critical literacy lens:

-

Disrupting the Commonplace: Keeping in mind that Maus I was first published as a novel in the mid-1980s, how did Spiegelman disrupt the commonplace by using the comics/graphica medium to tell this nonfiction story? Initially, the Maus series appeared in serial editions in RAW magazine (Wolk, 2007) . What made it stand out enough to be published in novel form? How do you think the animal symbolism of the novel relates to the idea of disrupting the commonplace? How do the images in the book convey the theme of overcoming oppression? [ Suggestion: In a creative writing course that I co-taught recently, the instructor and I had our students create their own social justice comics to share with the group. In addition, in a Graphic Literature Open Institute for the Red Clay Writing Project, our students (educators and preservice teachers) found a lesser-known graphic novel that related to social justice issues and shared a presentation to the class about why it should be taught in schools.]

-

Interrogating Multiple Viewpoints: How do both Art’s and Vladek’s narrative voices contribute to the telling of the story? Why is the framing device of Vladek’s story of the Holocaust told within Art’s modern-day perceptions of his father important? [ Suggestion : Students could write their own narrative or graphic narrative story that includes a narrative frame, or a story told through more than one character’s lens. Additionally, this novel could be compared and contrasted with the graphic memoir, The Complete Persepolis , by Marjane Satrapi (2007) , which also includes the framing device of an adult narrator’s reflections on a child’s experiences of the war in Tehran (Chute, 2010) ].

-

Focusing on Sociopolitical Issues: How did the Holocaust affect world history? How does it continue to affect sociopolitical issues in both Europe and the United States? What are some other conflicts that involve religious persecution, both past and present? [Suggestion: Before reading the book, students could complete a research project about the Holocaust, its beginnings, and its progression over time, so they will understand the context and its relationship to Vladek’s story. Additionally, students could discuss and research the Crusades and the parallels between this historical time period and the Holocaust.]

-

Taking a Stand and Promoting Social Justice: Why is it important to take a stand against religious and racial persecution? How do these issues still exist in modern society, and what can we do about them? [ Suggestion: Students could write an editorial for a newspaper about an issue related to persecution and what we as a school and/or community can do to further promote fairness and understanding.]

Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White

by Lila Quintero Weaver

In

Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White

(2012)

,

the images and words combine to show that the family,

having immigrated to the United States, was not

used to the racial divides that existed in Alabama during

the 1960s. The novel tells the story of the Quinteros,

an Argentinian family who moves to Alabama for

the father’s ministry job. Because of their roots, the

family initially views the segregation of the south from

a psychological distance, and they often feel shocked

and appalled by what they see. Particularly compelling

are the narrator’s statements, “The rules that

governed race relations were written down nowhere,

but you were supposed to know them anyway”

(p. 76)

and “I didn’t like that these dividing walls existed”

(p. 77)

. Perhaps because the Quinteros were outsiders

looking into the segregated South, they were better

able to see the injustices of the situation. Several

scenes show that the early adolescent narrator listened

to records by artists such as Joan Baez and read such

books as

Black Like Me

that belonged to her older

sister. Images in Figure 1 illustrate that the Quintero

girls clearly favored the ’60s artists who advocated for

social justice.

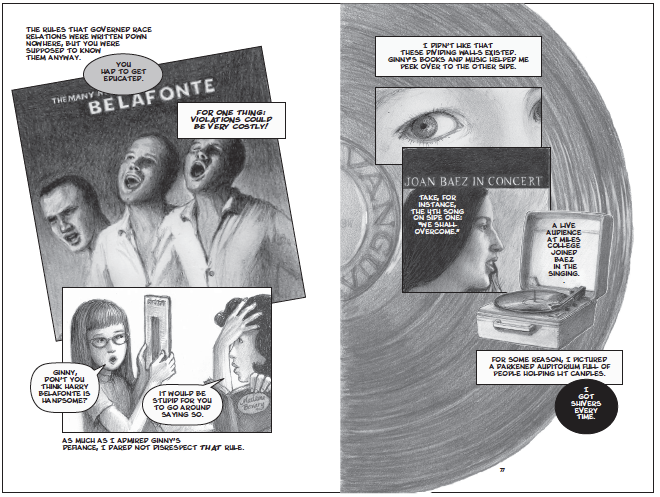

Lila was aware of the social norms that govern this small Alabama town, but she did not care to follow them. A closer look at Figure 1 shows that both Lila and her sister empathized with African Americans but initially did not want to claim this feeling for fear of being chastised. As her sister patted on her hair to make herself look more American, Lila asked, “Ginny, don’t you think Harry Belafonte is handsome?” Ginny responded, “It would be stupid for you to go around saying so” (p. 76) . Also, the reader should notice that Ginny is reading Madame Bovary , a British book, perhaps in an attempt to blend in with European American norms or to show that schools tend to give Eurocentric reading assignments.

However, the picture on the next page shows that in the privacy of their own home, the girls listened to such revolutionary songs as Joan Baez’s “We Shall Overcome” (p. 77) . As is typical of adolescent girls, Lila and Ginny struggle between fitting in and standing up for their beliefs. Their father, on the other hand, was more open with his anti-segregation beliefs. In the classroom, students who have read the text might be asked to turn through the pages of the book a second time and create a list of examples of the two girls seeking ways to be accepted by their peers. To encourage students’ careful analysis of the father in these terms, they might also be invited to identify particular images that show his response to segregation, and then to analyze commonalities within and differences across them.

Lila’s father was a preacher, and in several scenes, he showed opposition to segregation by such actions as eating in a restaurant that normally only served African American patrons. In one particularly compelling scene on page 96, Mr. Quintero invited the choir of an African American church to sing at a White church. As well intentioned as the act was, the members of Mr. Quintero’s congregation did not receive this action well. Lila noted, “To my father’s astonishment, church leaders demanded that the choir leave” (p. 97) . The pictures linked to this episode convey an interesting contrast between the welcome extended by the White church members upon first meeting Mr. Quintero to their looks of anger and dismay upon learning that he invited African American choir members to the church. The visuals, combined with the texts, show how hypocritical people can be. Visuals make juxtapositions between words and actions easier to comprehend than text alone.

When teaching this work through a critical literacy lens, it is imperative to notice student reactions to such a scene and provide them with opportunities to discuss these reactions with others. Before teaching this novel in a secondary classroom, it would also be important to prepare the students for some of the harsh and derogatory language used to describe African Americans. For instance, during this same episode, one of the church members made the statement, “Nigras? You invited Nigras?” (p. 97) . If the climate of the classroom is one in which a thoughtful discussion could be had, this scene could invite a teachable moment about why the treatment of both the visiting choir members and of Mr. Quintero was unjust.

In addition to being a messenger of social justice through its engagement with “real life” historical events, the graphic memoir Darkroom offers an opportunity to discuss social justice issues through symbolism. Many drawings in the novel, as aligned with the title, convey a contrast between light and dark imagery. Lila’s father, in addition to being a preacher, was a photographer. The book shows him developing pictures he took of protests and demonstrations that contributed to the civil rights movement. The phrase “darkroom” is symbolic of the divide between the races, specifically the Quinteros’s place in between Black and White as Argentinians of mixed Native American and European backgrounds. The light and dark imagery also juxtaposes the darkness of segregation’s cruelty versus the light of knowledge that comes from social activism. The title of the book serves as a roadmap to some of its themes, which is helpful, particularly to students who are learning to understand symbolism. In a classroom setting, students could talk about why the title is appropriate for the book on both a literal and metaphorical level.

The following can be a guide for discussing Darkroom with a critical literacy lens:

-

Disrupting the Commonplace: How do Lila and her family disrupt the commonplace when they interact with the African Americans in their community? At what point do they receive backlash, and how do they handle these interactions? How is their role as witnesses to segregation important to Lila’s narrative voice? How do the girls’ music tastes and choices show their disruption of the status quo, and why do you think they are hesitant to be vocal about it? [ Suggestion : Students could draw or create a map of their community and discuss with the class or in a written response who feels a part of the community and who might feel like an outsider. Additionally, they could think about how to be more inclusive of others in the community. Another potential activity could be to make a list of pop culture preferences, such as favorite music and TV shows, and discuss how and if and why people tend to cross cultures with these tastes.]

-

Interrogating Multiple Viewpoints: How is the different perspective of Argentinians important in this story? How does the girls’ conversation around pop culture reveal the tension they feel because they are not members of either the privileged or opgpressed population in this community? [ Suggestion : Students can find specific images in the book that show the Quinteros bearing witness to the events of the Jim Crow segregation, both when they directly intervene and when Mr. Quintero tells the story of the events with his camera. In particular, the scene at the church described above and the incident in which Mr. Quintero takes pictures of the civil rights demonstration are powerful scenes from which to begin discussions about multiple viewpoints of an incident.]

-

Focusing on Sociopolitical Issues: What does the reader learn about the Jim Crow South and its injustices from reading this book? Why do you think the title is important when thinking about the issues of racial injustice that the book explores? [ Suggestion : If students have read other books about this topic, such as Christopher Paul Curtis’s The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963 (1995) , they could do a compare and contrast essay about what the book taught them about the Jim Crow South and how it is different when told through another character’s lens.]

-

Taking a Stand and Promoting Social Justice: What forms of injustice still exist in the United States today, and what can we do about them? How can the study of literature make a difference in the process? What forms of writing can tackle this issue? How might we change our own roles within our communities to encourage more inclusion? [ Suggestion : Students can read nonfiction articles about such recent events as the Trayvon Martin trial and the Ferguson riots. This current events examination could lead to a discussion and writing prompts about how prejudice still exists and what we can do to prevent such tragic instances. Additionally, students can have a dialogue about how communities reacted to these acts of violence and how they could have been handled differently.]

A Game for Swallows

by Zeina Abirached

A Game for Swallows

(2007)

is an example of an

international YA graphic novel with the theme of

overcoming oppression. This book describes a war

in Lebanon that takes place between two religious

groups, Christians and Muslims. Two prime examples

of the image aiding the text in theme depiction are the

wall painting of Moses and the Hebrews fleeing Egypt

(p. 39)

and the map of Beirut, Lebanon, that shows

West Beirut labeled as Muslim and East Beirut labeled

as Christian

(p. 8)

.

Zeina and her family members are Lebanese Christians who are trying to survive the war-torn city. In this book, war is a major oppressor, along with the religious divisions. Similar to what we see in Maus I and Darkroom , the contrasts of dark and light in this book depict the darkness of war contrasted with the hope that Zeina and her family are able to retain in the situation. In spite of the brutal war on their home soil, Zeina and her family members are able to rely on each other and survive.

Ultimately, the only way the family can fully escape the oppression is to leave the country. Abirached, the author of this autobiographical graphic memoir, eventually moved to France, and the book was translated from English into French. However, the Arabic lettering of her name at the end of the book shows her attempt to hold on to her home language and culture, despite having to physically leave Lebanon.

Students should be encouraged to read through a critical lens focused on how the story has both an internal and an external conflict. The external conflict is revealed when the parents have to go to the other side of the city to help the grandmother, and the children and their neighbors do not know if and when they will return safely. The internal conflict is seen through the people trapped in the building who, during the fighting, still try to maintain a sense of peace, both inner and outer, amid the frightening events that are taking place. However, there might be an even larger internal conflict occurring—the attempt to maintain one’s identity even when one’s home is being destroyed—a concept of particular relevance to adolescents. Critical reading skills can help students to recognize these themes and conflicts. Taken a step further, critical literacy discussions can encourage students to see connections to their own lives and enact change.

Discussing religion in the classroom can be complicated, but conversations about the political implications of religious wars can be had in a safe classroom space. The following could be an inquiry process for studying this novel in a critical literacy context:

-

Disrupting the Commonplace: The children’s neighbors, in addition to their actual parents, serve in caretaker roles to the children. Can parental figures exist outside of our immediate families? How should we trouble and question the definition of a traditional “nuclear” family? Additionally, how do you think this book questions the idea that war is a solution to international problems? [ Suggestion : Students could brainstorm about who else can serve in parental roles in addition to actual parents. A short story or a children’s picturebook with similar thematic issues could be read to the class to initiate a dialogue about alternative family structures. For the discussion of war and conflict, students could identify alternative methods of handling conflict, both internal and external.]

-

Interrogating Multiple Viewpoints: The story is told from Zeina’s perspective, so we see her childlike response to events and also her looking back on the situation as an adult. How would the story be different if it were told from another point of view? What if the story were told from a Lebanese Muslim’s point of view rather than that of a Lebanese Christian? [ Suggestion : Students could choose a section of the novel to rewrite, in either narrative or graphic narrative form, from the perspective of a character of a different religious/cultural background.]

-

Focusing on Sociopolitical Issues: How do the sociocultural and sociopolitical events in Lebanon during the 1980s influence the story? Why is Zeina’s position as a young female narrator important in the telling of this story? [ Suggestion : Students could learn more about the historical background behind Lebanon and the war. Additionally, this novel could be compared and contrasted to other novels about war, particularly those that involve a young narrator.]

-

Taking a Stand and Promoting Social Justice: Why is it important for us to hear more voices from the Middle East? How and why are women’s voices becoming more prevalent in the Middle East and throughout the world? [ Suggestion : As a parallel, students could study and respond to the Afghan Women’s Writing Project website ( http://awwproject.org ) and discuss how issues in Afghanistan both parallel and differ from those in Lebanon. This website has several poems and nonfiction accounts written by Afghan women that would be interesting to study alongside this novel. Students could write responses to the poems and stories by the Afghan women and, if they choose, post their responses to the website.]

Conclusion

The three graphic memoirs discussed, like other writings about social justice, contain sensitive issues. Before bringing them into the classroom, it may be necessary to have a prereading dialogue about the subject matter of the books and why it is important to read them. As Letcher (2008) reminds us, since some graphic books deal with harsh topics, “teachers . . . should be aware, as with all books, of the age and readiness of their students” (p. 94) . The graphic novels discussed in this article tell the truth of oppressed people and sometimes utilize harsh language and strong imagery to do so. However, all three books examine social justice issues that are productive to bring to light. Additionally, graphic novels that interrogate historical topics are conducive to writing activities. Letcher (2008) notes that because of their appeal, “teachers can and should utilize that engagement and allow graphic novels to serve as a bridge to other texts, as a forum for teaching literary terms and techniques, or as a basis for writing projects” (p. 94).

All three of these graphic memoirs engage in a deep and thought-provoking way with history and its impact on real people. Maus I (1986) describes a group of people who were oppressed because of their religion and racial heritage. Darkroom (2012) recounts a tale of people who both witnessed and experienced oppression due to race and who were silenced when they attempted to advocate for a marginalized group of people. A Game for Swallows (2007) depicts a family who faced the ultimate oppressor, war, which resulted from religious conflict. All three books depict a period of historical significance, its social justice issues, and people who were affected by the oppression of the surrounding events . . . and found ways to overcome it. My hope is that these and other graphic memoirs that convey social justice issues will make their way into more secondary classrooms.

As a student who was labeled as both “gifted” and “learning disabled” as an adolescent, I know that people can be oppressed or treated unfairly regardless of the racial, socioeconomic, or gender group in which others envision them, simply because people are afraid of that which is unfamiliar. Since adolescents are grappling with issues of self-identity, it is important to introduce them to these social justice concepts at an early age when they can easily empathize with people who are trying to find themselves and who want to be accepted for who they are. Learning activities focused through critical literacy and social justice lenses will help them to see how the issues faced by the protagonists apply to their own lives. Graphic memoirs such as Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale , Darkroom: A Memoir of Black & White, and A Game for Swallows ) are important for consideration in secondary classrooms.

Margaret Robbins is a second-year doctoral student in the Language and Literacy Education department at the University of Georgia. She is a graduate assistant for the Red Clay Writing Project and the English Education focus area. She has also worked with the Kennesaw Mountain Writing Project. Margaret taught high school English for three years and middle school reading and language arts for seven years. Currently, she is the Poetry and Arts Editor for the Journal of Language and Literacy Education . She has been an avid reader of YA literature for many years, and her research interests include children’s/YA literature, multicultural education, critical literacy, critical media literacy, and pop culture.

|

Appendix 1: Middle School (8th Grade) Common Core State Standards Related to Critical Literacy

[Website Referenced: http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/W/8/ ] |

||

|---|---|---|

| Standard Number | Definition | Relationship to Critical Literacy |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.8.1 | Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence | Students learn to form an opinion and to address the counterargument; both are steps toward critical literacy and praxis. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.8.1.A | Introduce claim(s), acknowledge and distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and organize the reasons and evidence logically. | Students learn to consider the opposing point of view. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.8.1.B | Support claim(s) with logical reasoning and relevant evidence, using accurate, credible sources and demonstrating an understanding of the topic or text. | Students learn to respectfully disagree with people and to form a convincing argument. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.8.1.C | Use words, phrases, and clauses to create cohesion and clarify the relationships among claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence. | Students learn to consider the opposing point of view. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.8.1 | Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. | Students engage in critical reading, a necessary step toward critical literacy. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.8.2 | Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to the characters, setting, and plot; provide an objective summary of the text. | Students learn critical reading skills and to develop empathy with the characters and other people. |

|

Appendix 2: High School (9th–10th Grade) Standards Related to Critical Literacy

Website Referenced: http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/W/9-10/ ] |

||

|---|---|---|

| Standard Number | Explanation | Relationship to Critical Literacy |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1 | Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. | Students learn to form an opinion and to address the counterargument. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1.A | Introduce precise claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that establishes clear relationships among claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence. | Students learn to consider multiple perspectives. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1.B | Develop claim(s) and counterclaims fairly, supplying evidence for each while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both in a manner that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level and concerns. | Students gain an understanding of audience, multiple points of view, and how to argue a viewpoint for the purpose of change. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1.C | Use words, phrases, and clauses to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships between claim(s) and reasons, between reasons and evidence, and between claim(s) and counterclaims. | Students understand a counterclaim or a different perspective. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.3.A | Engage and orient the reader by setting out a problem, situation, or observation, establishing one or multiple point(s) of view, and introducing a narrator and/or characters; create a smooth progression of experiences or events. | Students learn to understand an alternative viewpoint. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.1 | Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. | Students engage in critical reading, a necessary step toward critical literacy. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.2 | Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze in detail its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details; provide an objective summary of the text. | Students engage in critical reading, a necessary step toward critical literacy. |

| CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.9-10.3 | Analyze how complex characters (e.g., those with multiple or conflicting motivations) develop over the course of a text, interact with other characters, and advance the plot or develop the theme. | Students engage in critical reading, a necessary step toward critical literacy. |

Recommended Resource Books on Teaching Graphic Novels

Abel, J., & Madden, M. (2008). Drawing words and writing pictures. New York, NY: First Second.

Carter, J. B. (Ed.). (2007). Building literary connections with graphic novels: Page by page, panel by panel , Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Cary, S. (2004). Going graphic: Comics at work in the multilingual classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Thompson, T. (2008). Adventures in graphica: Using comics and graphic novels to teach comprehension, 2–6. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Monnin, K. (2013). Teaching graphic novels: Practical strategies for the secondary ELA classroom. Gainesville, FL: Maupin House.

Suggested Social Justice Graphic Novels for Students

(with genre and appropriate age level)

Abirached, Z. (2008). I remember Beirut. Minneapolis, MN: Graphic Universe. (Memoir/Middle School and High School)

Anderson, H. C. (2005). King: A comics biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books. (Biography/ High School)

Backderf, D. (2012). My friend Dahmer. New York, NY: Abrams ComicArts. (Memoir/High School)

Bechdel, A. (2006). Fun home. Boston, MA: Mariner Books. (Memoir/College and Graduate Level)

Bechdel, A. (2012). Are you my mother? Boston. MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. (Memoir/College and Graduate Level)

Curtis, C. (1995) The Watsons go to Birmingham. New York: Random House.

Deutsch, B. (2010). How Mirka got her sword. New York, NY: Amulet Books. (Fiction/Middle School and Early High School)

Deutsch, B. (2012). How Mirka met a meteorite. New York, NY: Amulet Books. (Fiction/Middle School and Early High School)

Kellas, I. (1983). Peace for beginners. London, UK: Writers and Readers. (Nonfiction/Middle School)

McKay, S. E., & LaFrance, D. (2013). War brothers: The graphic novel. Toronto, ONT: Annick Press. (Historical and Fact-based Fiction/Late Middle School and High School)

Moore, A., & Gibbons, D. (1986). The watchmen. New York, NY: DC Comics. (Fiction/High School)

Rius. (1976). Marx for beginners. New York, NY: Pantheon. (Nonfiction/Middle School)

Spiegelman, A. (2004). In the shadow of no towers. New York, NY: Pantheon. (Memoir/Advanced Middle School and High School)

Satrapi, M. (2007). The complete Persepolis. New York, NY: Pantheon. (Memoir/High School or College)

Telegeimer, R. (2012). Drama. New York, NY: Scholastic. (Fiction/ Middle School and Early High School)

Tamaki, M., & Tamaki, J. (2010). Skim. Toronto, ONT: Groundwood Books. (Fiction/High School)

Ware, C. (2003). Jimmy Corrigan: The smartest kid on earth. New York, NY: Pantheon. (Fiction/Advanced High School)

Yang, G. L. (2006). American born Chinese. New York, NY: Square Fish. (Fiction/High School)

Yang, G. L. (2013). Boxers. New York, NY: First Second. (High School)

Yang, G. L. (2013). Saints. New York, NY: First Second. (High School)

References

Abirached, Z. (2007). A game for swallows (E. Gauvin, Trans.) Minneapolis, MN: Graphic Universe .

Behrman, E. (2006). Teaching about language, power, and text: A review of classroom practices that support critical literacy. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy , 49, 490–498.

Carter, J. B. (2008). Die a graphic death: Revisiting the death of genre with graphic novels, or “Why won’t you just die already?” The Alan Review , 36(1), 15–25.

Cary, S. (2004). Going graphic: Comics at work in the multilingual classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Cervetti, G., Pardales, M. J., & Damico, J. S. (2001, April). A tale of differences: Comparing the traditions, perspectives, and educational goals of critical reading and critical literacy. Reading Online , 4(9). Retrieved from http://www.readingonline.org/articles/cervetti .

Chute, H. (2010). Graphic narratives as witness: Marjane Satrapi and the texture of retracing. In H. Chute, Graphic women: Life narrative & contemporary comics (pp. 135–173). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Cole, P. (2013). Becoming thrice-born: 10th-grade history students inquire into the rights to culture, identity, and freedom of thought. In J. Allen and L. Alexander (Eds.), A critical inquiry framework for k–12 teachers (pp. 109–126). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Comber, B. (2001). Negotiating critical literacies. School Talk , 6(3), 1–3.

Curtis, C. P. (1995). The Watsons go to Birmingham—1963. New York, NY: Delacorte.

Eisner, W. (1978). A contract with God and other tenement stories. New York, NY: Baronet Press.

Hunt, J. (2008). Borderlands: Worth a thousand words. The Horn Book Magazine , 84, 421–426.

Janks, H. (2000). Domination, access, diversity, and design: A synthesis for critical literacy education. Educational Review , 52, 15–30.

Letcher, M. (2008). Off the shelves: Graphically speaking: Graphic novels with appeal for teens and teachers. The English Journal , 98(1), 93–97.

Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts , 79, 382–392.

McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding comics: The invisible art. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common core state standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/ela-literacy .

Satrapi, M. (2007). The complete Persepolis. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Schwartz, G. (2010). Graphic novels, new literacies, and good ole social justice. The ALAN Review , 37(3), 71–75.

Spiegelman, A. (1986). Maus I: A survivor’s tale. New York, NY: Pantheon.

Thompson, T. (2008). Adventures in graphica: Using comics and graphic novels to teach comprehension , 2–6. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Weaver, L. (2012). Darkroom: A memoir in black and white. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press.

Whitlock, G., & Poletti, A. (2008). Self-regarding art. Biography , 31(1), v–xxiii. Retrieved from http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/bio/summary/v031/31.l.whitlock.html .

Wolk, D. (2007). Reading comics: How graphic novels work and what they mean. Da Capo Press.

by MB