Two Tourists in Japan

Frank Doleshy, Seattle, Wash.

Part III: R. metternichii var. pentamerum, R. brachycarpum and R. japonicum

Return to the North

October 21st was a summery day at Kumamoto, on the south island of Kyushu, and we had some misgivings when mailing our warm-weather clothing back to the U.S. The next evening, however, we were 825 kilometers to the northeast, on the main island of Honshu, and our train climbed through a cold mist as it approached the Jo-Shin-Etsu Plateau.

This choice of location was a strange and fortunate compromise. Our travel agent had advocated the Nikko area, further east. But we promised him that we would go to this great tourist attraction when we were 90 years old and traveling by wheelchair. He then gracefully admitted that there was no law which required every foreign tourist to go to Nikko, and he mentioned the Japanese Alps, to the west. But we had a vague impression that these were outside of

R. degronianum

territory, so we decided to try Jo-Shin-Etsu, midway between Nikko and the Alps.

Our destination here was the Hotel Sun Valley at Kusatsu, owned by Mr. Yoshio Hagiwara, an amateur botanist. To greet us, he had gathered his staff in the lobby, and we were led to the elaborately comfortable Special Room. An English-speaking assistant manager shared our welcoming tea and started the bath water. Also, in case we failed to notice, he called attention to one of the room decorations: a 10 year-old container-grown

R. degronianum

with beautiful pinkish-buff indumentum. Tomorrow, he explained, we'd see these plants by the thousands. And, as he outlined our schedule, we decided that bedtime should follow soon after bath and dinner.

|

|

|

Fig. 41.

R. metternichii

var.

pentamerum

at lower left; R. brachycarpum at right. Near Mt. Shirane road, 1700m. |

Fig. 42. Firs and bamboo at timberline,

Mt. Shirane, 2000m. |

Foggy Craters

Heading up the mountain road in a hotel car the next morning, our destination was the dormant volcanic cone of Mt. Shirane. Visibility was limited by the thick fog, and we were startled at the sudden appearance of Shakunage (i.e., evergreen Rhododendron). We saw none until reaching a rocky plateau, and then were surrounded. The driver smiled at our obvious delight but didn't change speed; he evidently had a copy of our schedule and took us straight to the foot of the Kazan aerial tramway, or "ropeway."

We were well-seasoned ropeway travelers, but this was a new experience. Instead of the usual broad view, the only things visible through the fog were an occasional tree-top and one rock cliff. Coming back to earth at the uphill station (2040 m. elevation), we knew from the post cards that we were in an area of crater lakes and steam jets, ringed by other great landmark peaks, but we couldn't see any of these things. We hesitated to start off in the fog, but changed our minds when we found that the ropeway station sold a good map, entirely in Japanese but showing all contours, craters and trails.

Taking the main trail, we first came to a highway pass where about 50 tour buses were parked. The cheerful conductors (always girls) seemed undisturbed as their honeymoon couples and elderly ladies' clubs disappeared in the direction of Mt. Shirane cone, so we went on up and found the rim of the largest crater lake. The water was invisible 20 meters below, so the only thing to do was scramble down. Finally it appeared, green and steaming. The temperature was pleasant enough to suggest but not quite compel a swim, so we refrained.

Feeling competent as tourists, we decided it was time to change back to somewhat less competent botanists.

Returning to the ropeway, we took time to look at the vegetation along the trail. The clumps of stunted firs and pines were much like their timberline counterparts at the same elevation (slightly above 2000 m.) in the western U.S. However, the carpet of plants between the trees was the real surprise: not heather or juniper, but bamboo! This was a dwarf species, growing about

1

/z m. tall, and it covered practically all the open ground, except where very steep or rocky. In the gaps were small ericaceous plants-

Vaccinium

, probably some azalea, and almost certainly

Gaultheria miqueliana

. But the evergreen Rhododendrons which dominated the lower mountain slopes were completely absent at this level.

Green and Red Foliage

On the downhill ropeway trip we were able to see the ground. The upper part of the route was within the zone of small conifers and bamboo, and the bamboo continued all the way down, occupying any reasonably smooth or gentle slope. But we started to see

R. degronianum

and

R. brachycarpum

at ca. 1800 m., and these became abundant on a series of rocky but not extremely steep slopes extending down from an elevation of about 1750 m. The slopes faced southeast and contained few large trees, so shade was practically nil.

From our vantage point, 15-30 m. above the ground, it was easy to distinguish the two species. They grew side by side as rounded shrubs, 1-1½ m. tall, but the foliage of

R. degronianum

was almost blue-gray, while that of

R. brachycarpum

was a bright, deep yellow-green, accentuated by the yellow buds. Also, the latter species was somewhat more open in habit. Their companion plants-including

Vaccinium

and

Sorbus

-had autumn foliage in every shade of bronze, purple, scarlet and orange, and the scene was as vivid as silk comforters hanging out to be aired. Like us, the uphill passengers were leaning out of their windows taking pictures, and we wondered how often a camera was dropped.

The hotel car appeared at the downhill station shortly after we arrived, bringing Mr. Hagiwara with his much used copy of Makino's

Illustrated Flora of Japan

, and we started to botanize our way down the road.

R. degronianum

, we learned, was called the Azuma Shakunage, or just plain Shakunage, while

R.brachycarpum

was locally called the Hakusan Shakunage. (Another name for this indumentum clad phase is Shirobana Shakunage.)

The first stop was a small lake near the ropeway station, ca. 1500 m., and we were introduced to

Hydrangea paniculata

,

Ilex crenata

,

Rhus trichocarpa

, and a Vaccinium with highly edible fruit. Also, we were surprised to find one large and attractive plant of

R. degronianum

within the circle of stunted vegetation which surrounded the lake. Whatever the cause of stunting - late snow melt, cold air accumulation, or excessive moisture - this circle did not look like a very good Rhododendron habitat. However, it is only by colonizing such unlikely - looking spots that the Rhododendrons can avoid the competition of bamboo, which seems able to crowd everything else out of any reasonably good patch of soil.

Continuing down, we saw that the two Rhododendrons dominated all steep or rocky areas to a rather sharp break - off at 1440 m. elevation. Scattered individuals could be seen to 1400 m., but none at all below that level.

Approaching the 1250 m. elevation of the hotel, we came back into reforested Larch and noticed interesting things scattered through this open woodland. Some of the trees with bright scarlet foliage were

Acer tschonoskii

, and the majestic shrubs with maroon foliage turned out to be

R. japonicum

, the Renge Tsutsuji.

Dash to the Seeds

Eating a late lunch, we wondered when it would be possible to get some Rhododendron seed. Clearly, Mr. Hagiwara wanted to show us all the interesting plants and had no idea of treating us as narrow Rhododendron specialists. But, on the other hand, we had never seen any cultivated plants of

R. degronianum

or

R. brachycarpum

with the distinction of those up the road, and it seemed unthinkable not to bring back some seed. If we resumed our tour after lunch, Mr. Hagiwara would surely want to show us other things besides Rhododendrons, and it was also obvious that plans had been made for the following day.

Another worry was the seed shortage; we had not yet seen a single seed capsule on any Rhododendron and had been told by Mr. Hagiwara that it was an exceptionally bad seed year.

Now or never, it seemed. So, at 3:00 P.M., I quietly slipped out and walked or trotted up 4 kilometers of the mountain road, arriving at the Shakunage thickets with 1¼ hours of remaining daylight. Here, for the first time, I could see that the contemporaries of Daniel Boone were accurate when they wrote about the "Rosebay Hells" of the Appalachian Mountains. Some plants were growing in a thin layer of pumice soil on top of head-high rocks, and others were twisted around the rocks or had generated a grating of bar-like branches from rock to rock. The crash through approach would have been heart-breaking, in the most beautiful foliage I had ever seen. (Also, it didn't work.) But, after adopting a more catlike or gopher-like mode of travel, I got into the thicket and found that perhaps 1 plant out of 15 had trusses of good capsules.

The two species grew over, under and through each other, but it appeared that

R. degronianum

was slightly more effective in the competition for space, and that

R. brachycarpum

survived because it was taller. The latter plant grew to heights of 2½-3 m. and occasionally almost 4 m., with a width of 1½-2 m. (but was sometimes broader than tall).

R. degronianum

in a few cases reached a height of 2½ m. but mostly remained under 1¾ m., often growing very broad and dense, with several stems up to 15 cm. in diameter. Numerically, there were probably three plants of

R. degronianum

for each one of

R. brachycarpum

.

While riding the ropeway we had seen the difference in leaf color. And, close up, the foliage and habit of the two species were very distinct.

R. brachycarpum

was more open, its large leaves were rounded or slightly heart-shaped at the base, and the undersurfaces were covered with a thin, pale indumentum. Three collected leaves had blade lengths of 11.9-13.3 cm., blade width of 4.7-5.3 cm., and a distinctly elliptic shape.

In contrast,

R. degronianum

generally looked like a dense version of

R. yakushimanum

. As mentioned in Part I, I had seen the Yaku plant only four days earlier, and the close similarity of

R. degronianum

was hard to believe. On the latter plant the leaves were more dull and bluish, the stems and capsules had less hair (but the top leaf surfaces had more hair vestiges), and the bare trunks and stems were not so long and straight. But these differences were less striking than the identical features, and the close similarity of these two plants is further confirmed by the measurements and counts given in the final part of this article.

With

R. degronianum

and

R. brachycarpum

growing in such leaf-rubbing proximity, I looked for evidence of natural hybridization, but saw none. Also, the young plants since raised from the collected seed appear entirely distinct. Obviously, crossing would be prevented by a difference in flowering season, but I am not sure that this is the complete explanation and suspect that there may be some additional barrier to crossing. (Tiara, in the 1948 Royal Horticultural Society

Rhododendron Year Book

, p. 126, states that

R. hidaense

is considered a hybrid between these two plants. However, he does not specify that this is a natural hybrid, and I have not been able to find any other reference to such a hybrid in the literature.)

99.9% Purity

The practical problem at hand on the afternoon of October 23rd was to pick the seed without getting it mixed. With time limitations and difficult terrain, it did not seem feasible to go around to plants of one species first, and then start on the other. Therefore, the course of events was to approach a

R. degronianum

, double-check the leaves, check the large label in the seed bag, pick capsules and a confirming leaf, dust off outside of seed bag and put it in my flight bag, scour hands and sweaty hair with a paper towel, dust clothing - and then see if the next seed-bearing plant was

R. degronianum

or

R. brachycarpum

.

|

|

Fig. 43. Shakunage thicket at the 1450 m. level. Source

of seed collections No. 12 and 13. |

If this sounds like outlandish over caution, I suspect that the reader has never been disappointed by badly collected seed, or seed irresponsibly labeled as "selfed." And, at risk of hearing comments about disloyalty, I'll admit that I wasn't primarily thinking about my fellow Pacific Northwest growers, who can usually buy the things they want. Instead, I was more worried about getting good seed for growers in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, etc., where these plants are not so easy to get.

The

R. degronianum

is our seed collection No. 12, and the

R. brachycarpum

No. 13.

Approaching darkness finally increased the risk of error, and it was time to start walking down the road. The time pressure, now, applied to getting back, bathing, eating dinner, and going to the lobby in meticulous Japanese attire to meet Mr. Hagiwara's friend, Professor Kitazawa, of the Bunan Gakuen. The trip was much speeded by a friendly driver who gave me a lift, and the evening started on schedule. Mr. Hagiwara showed his excellent color slides of the local plants in springtime, while Professor Kitazawa gave us explanations through an English-speaking member of the hotel staff.

|

|

Fig. 44. Botanizing near Kusatsu: Mr. Doleshy, Mr.

Hagiwara, Sr., Professor Kitazawa and Mr. Hagiwara, Jr. |

The Kusatsu Area

With this as an introduction, we went out the next morning to collect seeds. At latitude 36°40' N., 1250 m. above sea level, we were in a transitional zone with a rich mixture of temperate and boreal plants. Our friends said that winter temperatures were commonly -20°C. (-4° F.). But, at least in late winter, there is undoubtedly a thick snow blanket.

The Larch woodland came right up to the edge of the hotel grounds, and our botanizing started immediately. We were never more than one kilometer from the hotel, but the seed haul included such interesting plants as

Vaccinium ciliatum

, large and deciduous

Gentiana triflora

, still opening beautiful blue flowers although some seed was ripe;

Lysimachia clethroides

, a white-flowered member of the Primrose Family; and

Sorbus commixta

, which must be one of the most red foliaged of the Mountain Ashes. The only Rhododendron collected here was

japonicum

, which grew to a height of 2 m. The maroon leaves would soon drop, but the capsules were still very green - some obviously juicy and immature. We picked those which seemed to have any possibilities as our No. 14, and have been amazed at a germination rate of more than 90%, followed by rapid growth.

R. japonicum

grows from Kyushu to Hokkaido, almost spanning the length of Japan. Flowers are from golden yellow to vermilion, and those A.R.S. members who attended the Tacoma Annual Convention will remember the interesting photographs shown by Dr. Creech. He has found the flowers more reddish in the northern part of the range, and we therefore expect orange to reddish flowers from our seed. The contrast between this plant and the dwarf, evergreen

R. kiusianum

is striking and illustrates the extreme diversity of the Azalea group.

After lunch and an extensive labeling session with Professor Kitazawa, we started off on our afternoon tour to the high-altitude bamboo and conifer country, but were able to stop for a few minutes under the ropeway, at 1700 m. Here, the two kinds of Shakunage grew as rounded, attractive shrubs. Except for smaller stature, they appeared the same as those at 1450 m., which supplied the previous day's seed collections. There was no marked change in leaf size or color at the higher elevation, and seed was just as scarce. Up here, however, we did get a small amount of

R. brachycarpum

seed, as No. 15, and the corresponding leaf has a blade length of 11.7 cm. and width of 5.2 cm.

Returning in the late afternoon, we stopped at 1450 m. to get a soil sample. This is completely unlike the decayed granite of Yakushima; instead, it appears to be a gritty but not gravely volcanic material brought clown by gravity, wind and water. Layers a few centimeters thick, on top of solid rock, seem ample for the Shakunage. Our tests give an approximate pH of 5.20-5.25, slightly more acid than the Yakushima soil.

Departure

Here we said goodbye, for 1965, to the Rhododendron habitats of Japan. Our remaining day and a half in Tokyo was spent mostly on seed extraction, packing and mailing - and the hotel staff must have thought we were collecting their envelopes as souvenirs. Also, we left them a very highly polished desk, as a result of clean - ups which followed the handling of each number.

All mailings were in Seattle the day after we arrived. Dr. Brown, of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Plant Quarantine Division, brought out the cardboard box which he had placed in his large refrigerator for us, and gently pointed out that we had not quite succeeded in filling it. But we'll try again, in the future.

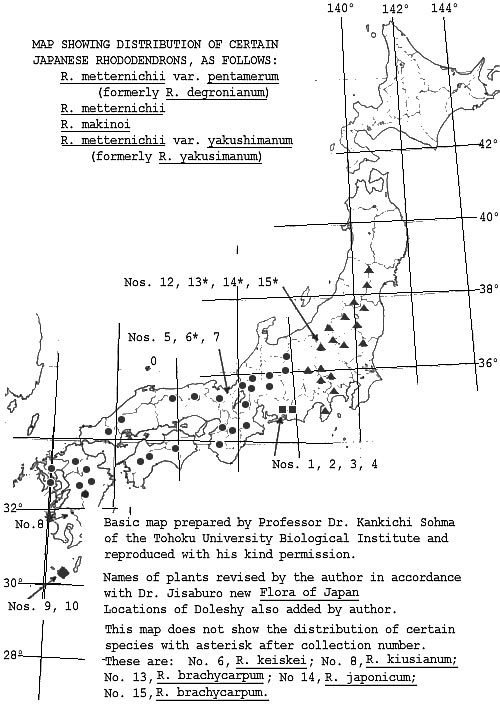

Busy Aftermath

The seven months since then have included much correspondence with people I have come to regard not only as major authorities but also as friends: Dr. Serbin in Hartford, Conn., Dr. Rokujo in Osaka, Mr. Wada in Yokohama, Dr. Sohma of the Tohoku University Biological Institute, Dr. Sleumer of the Rijksherbarium, Leiden, and, particularly, Mr. Nitzelius of the Goteborg Botanic Garden. A major topic of this correspondence has been proper naming and classification. We had labeled our collections with the names popularly used for these Rhododendrons in the U.S. However, we became increasingly aware of the opinion that some of these names were based on minor differences and should be discarded as superfluous.

A general house-cleaning and simplification was undertaken by Mr. Nitzelius in 1961, when he prepared his paper entitled "Notes on Some Japanese Species of the Genus Rhododendron,"*

* Acta Horti Gotoburgensis, Vol. XXIVA (1961), pages 135-174.

referred to in Part II. He concludes that

R. metternichii

,

R. degronianum

,

R. makinoi

and

R. yakushimanum

should be brought together and treated as one species, to be called

R. metternichii

. Within this consolidated species, he considers the former

R. makinoi

and

R. yakushimanum

as varieties. Regarding

R. fauriei

(or

fauriae)

and

R. brachycarpum

, he considers both as members of the same species, properly to be called

R. brachycarpum

. He does not recognize varieties or forms of this latter species but suggests that certain variants be treated as cultivars.

We read this study with interest and much agreement. However, we also wanted to obtain a current and authoritative Japanese opinion, and this became available in Dr. Jisaburo Ohwi's new English-language

Flora of Japan

, published in 1965 by the Smithsonian Institution.

This is the only English language flora of Japan and is the first in any European language since 1879. Both Dr. Sohma and Mr. Nitzelius drew our attention to this work, and we have also learned that it was welcomed with much respect by interested individuals in the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Ohwi does not make such a sweeping consolidation as Nitzelius. He treats

R. metternichii

,

R. degronianum

and

R. yakushimanum

as members of one species, properly to be called

R. metternichii

, but he maintains

R. makinoi

as a separate species. Also in addition to the typical

R. metternichii

, he recognizes varieties which correspond with the former

R. degronianum

and the former

R. yakushimanum

, plus a var.

hondoense

, with thinner, paler indumentum. He follows Nitzelius in considering

R. fauriei

and

R. brachycarpum

as one species, with

R. brachycarpum

the correct name, but he recognizes the plants with indumentum as a separate variety and also recognizes a form with petaloid stamens.

For full discussion of these revisions, interested readers should consult the Nitzelius paper and the Rhododendron section of the new Ohwi

Flora

. However, for people who are remote from large libraries, this advice may be rather difficult and expensive to follow. Therefore, it is to be hoped that an expanded A.R.S. publications program will make it possible to distribute such literature in the form of reasonably-priced reprints.

I can only comment on these revisions as an amateur. However, it may be appropriate to say something about the differences between the Nitzelius names and the Ohwi names. These differences may be resolved into two questions: Should

R. makinoi

be treated as a separate species? And, within the Japanese species, what basis do we have for distinguishing separate varieties?

The Status of

R. makinoi

The

R. makinoi

question has never had an easy answer, and many names have been proposed for this puzzling plant. Nitzelius considers it a variety of

R. metternichii

, arguing that there is a gradual transition from ordinary

R. metternichii

to the extremely narrow-leafed plant which has been called

R. makinoi

. Narrow-leafed transition types, he believes, may be found in the natural populations of

R. metternichii

located in many parts of central and southern Japan, completely outside the accepted range of

R. makinoi

. One notable example, which he illustrates by photograph, is a plant grown at Goteborg from seed collected in 1952 at Mt. Hiko, northern Kyushu. Also, he cites two similar herbarium specimens from Shikoku and another specimen from the Yamato area of Honshu.

His evidence certainly suggests that the narrow-leafed plant should be considered a variety, at most, rather than a species. However, in order to make this proposition completely acceptable, it seems necessary to show that the narrow-leafed variant of

R. metternichii

occurs consistently as a more or less predictable component of the various natural populations, rather than as an occasional freak.

I am not so sure that this has been demonstrated as yet. Therefore, without any strong convictions one way or the other, I propose to follow Ohwi in regarding

R. makinoi

as a separate species, at least for the present.

Varieties of R. metternichii

Concerning the separation of

R. metternichii

into varieties, both writers accept this status for the Yaku plant.

However, Ohwi distinguishes two additional varieties which Nitzelius does not recognize. These are var.

hondoense

, with the thinner, paler indumentum, and var.

pentamerum

, which is essentially the former

R. degronianum.

I cannot express an opinion as to var.

hondoense

, because our observations were extremely limited. However, we spent more time among plants of the Azuma Shakunage (i.e., the former

R. degronianum)

, and could see that the impressions of U.S. growers were not entirely accurate. Popular literature has emphasized that this and the Yaku plant have 5-lobed flowers, while

R. metternichii

has 7-lobed flowers. Indeed, some writers have suggested that this is the sole basis for distinction.

Nitzelius, on the other hand, examined the type specimen of

R. metternichii

(collected by Siebold in 1829 and now preserved at Leiden), and found that two of the seed capsules were actually 8-chambered instead of 7-chamhered! He mentions other similar variation found within a single species (particularly in the Fortunei group), and he suggests that these numerical counts of flower and fruit parts are not a trustworthy basis for distinguishing the Japanese Rhododendrons.

We saw no flowers, but this opinion is supported by our capsule counts, as shown in the following summary:

|

Collection |

Number of Capsules | ||||

| Listed under popular name | 4-lobed | 5-lobed | 6-lobed | 7-lobed | 8-lobed |

| R. makinoi , No. 4, cult, plants, Horaiji Village | 0 | 5 | 35 | 16 | 0 |

| R. metternichii , No. 5 , in habitat, Iwaya Hill | (The very small sample counted were all 7s.) | ||||

| R. yakushimanum , No. 9, in habitat, lower Kuromi-dake | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| R. yakushimanum , No. 10, in habitat, upper Kuromi-dake | 1 | 63 | 15 | 8 | 0 |

| R. degronianum , No. 12, in habitat, Mt. Shirane | 0 | 38 | 23 | 13 | 1 |

| R. brachycarpum , No. 13, in habitat, Mt. Shirane (No deviation from 5s in a large sample.) | |||||

| The " R. degronianum " count is from the 75 normal, uninjured capsules in 10 complete trusses, undoubtedly from several different plants, and it is interesting that not a single one of these trusses consisted of capsules with a uniform lobe count. (Complete trusses were not obtained from the other plants because of more advanced ripening.) | |||||

Obviously, one should not depend on the number of capsule lobes when trying to identify the Yaku Shakunage (" R. yakushimanum ") or the Azuma Shakunage (" R. degronianum ).*

* Working with a cultivated plant of R. makinoi , I have attempted to determine the relationship between flower lobes and capsule lobes. No definite results can yet be given, because capsules are very green at time of writing. However, it appears that the number of flower lobes is no more uniform than the number of capsule lobes and should not be considered a reliable basis for identification

However, it seems interesting that the counts for these two Rhododendrons follow the same pattern of variation. Geographically, they are located 1000 kilometers apart (with typical

R, metternichii

in the great territory between). Yet there is this similarity in seed capsules, along with the already-mention-ed similarity in general appearance on firming the close kinship noted by Japanese observers and, perhaps, indicating that the two plants are more closely related to each other than to the intervening

R. metternichii.

Leaf details show additional close resemblance. We obtained 10 leaves of the Azuma Shakunage from plants which actually supplied our No. 12 seed collection. As dried specimens, they are much like our "Upper Trail" and "Lower Trail" collections of Yaku leaves-indeed, so similar that it would be nearly impossible to sort out the Azuma and Yaku leaves if they became mixed. In summary, they compare as follows:

| 14 Leaves, "Upper Trail" and "Lower Trail," Yaku Shakunage | 10 Leaves, Azuma Shakunage | |

| Length of blade, in cm. | 5.4-12.7 | 7.0-12.2 |

| Width of blade, in cm. | 1.7-4.1 | 2.2-3.8 |

| Number of narrow leaves, length at least 3X width | 9 | All 10 |

| Shape | Oblanceolate | Oblanceolate, with tendency toward oblong in some cases. |

| Indumentum | Smooth to spongy, some a very light buff. Color range HCC 09-010, often quite brownish. | Smooth to spongy, some a very light buff. Color range HCC 09-011. Colors more grayish than brownish, and generally a little more pink than the Yaku. |

| Upper surface | Bright, deep green. Smooth and rather shiny. | Gray-blue tone, with some vestiges of hairs. |

| Petiole | Very hairy. | Less densely hairy. |

Except for the tomentum on petioles and the colors of the living leaves, it is hard to find any substantial difference. Neither set, however, looks very much like the leaves of

R. metternichii

obtained on Iwaya Hill. (See Part I.)

With such close resemblance of the Yaku and Azuma plants, it seems that they should be treated as equally distinct from typical

R. metternichii

. That is, if the Yaku phase is maintained as a variety of

R. metternichii

, I believe that the Azuma phase should also be regarded as a variety. (True, there is much more geographical isolation in the case of the Yaku phase, but I do not believe that this is usually regarded as the

only

basis for distinguishing it as a variety.)

Ohwi recognizes both phases as varieties, while Nitzelius only recognizes the Yaku phase as a variety, and he merges the Azuma phase into typical

R. metternichii

. Therefore, in this case also, I propose to follow Ohwi. However, it is to be emphasized that the pioneering study by Nitzelius opened up the whole question of modifying the confused set of names which had been popularly used. His paper should be read by every grower who is interested in the Japanese Rhododendrons, regardless of agreement or disagreement with name proposals.

As a further refinement, it would seem reasonable to recognize the close similarity of the Yaku and Azuma varieties, perhaps by bringing them together into a sub-species of

R. metternichii

. However, a definite proposal along these lines would be outside the proper bounds of amateur comment (perhaps already overstepped in these articles), and I adhere to the Ohwi nomenclature, i.e.,

R. metternichii

var.

yakushimanum

* for the former

R. yakushimanum

and

*Accepted spellings of the Romaji translations of Japanese names have not remained uniform. In the 1941 Official Guide to Japan "sima" is used instead of "shima" as the general name for island. Thus yakushimanum correctly reflects the spelling at that time, while Ohwi's yakushimanum is in line with current spelling.

R. metternichii var. pentamerum for the former R. degronianum . Also, at this point, it is perhaps appropriate to repeat my impression that all Ponticum-group Rhododendrons on Yaku Island fall within var. yakushimanum . I saw no basis for dividing this compact population into two or more varieties. And, although there are doubtless some genetic differences between the individual plants, I saw no differences which were great enough to suggest the establishment of separate forms. (However, certain of the plants grown by Mr. Wada and certain of those found by Dr. Serbin may deserve distinction as forms.)

|

| Fig. 45 |

With regard to

R. fauriei - R. brachycarpum

, it is mentioned above that Ohwi follows Nitzelius in considering these plants as one species, properly called

R. brachycarpum

. Nitzelius does not recognize any varieties, but Ohwi distinguishes the tomentose phase as var.

roseum

. The view of each writer is consistent with his general philosophy as to names, and I can only comment that it would often be difficult to determine whether a particular plant fell within var.

roseum

or the typical phase. Therefore, any undue emphasis on this varietal distinction may be wasted effort.

In conclusion, I must say that no happier vacation trip can be imagined. One has the choice of worrying or not worrying about the food and water. We took the latter alternative, ate and drank everything, and never had cause for regret. Also, we were grateful to our friend Mike Young, at Horaiji, for giving us rather stringent instruction in Japanese table manners. After this, we sometimes hesitated for a moment at the proper treatment for an unfamiliar dish, but we never felt that we looked conspicuous.