F. W. Schumacher

Elinor Clarke, Ashville. Massachusetts

|

|

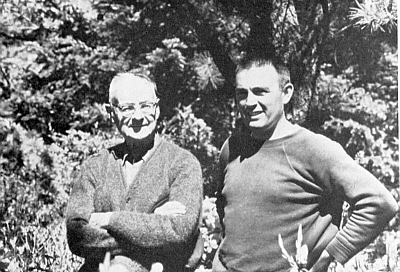

FIG. 65. Pictured are Fred Schumacher (L), and David

Allen, new owner of the Schumacher Seed Company. |

This is being written to celebrate the retirement of F. W. Schumacher of Sandwich, Mass., from the seed business he has run for nearly half a century. A year ago he sold this business, the extraordinary old house on the Hill built by a dancing-school teacher, as well as the Hill and almost all of the plant materials to David W. Allen of Hingham. Since the agreement included staying on for a year to help Allen learn the business, Schumacher's retirement has just taken effect. He and Louise have gone abroad on almost their first real vacation together. One can imagine them, free for the first time from unexpected shortages of supplies, the fantastic demands of customers, etc!

Friedrick W. Schumacher was born July 16, 1896 in Wolfenbuettel in northern Germany. His father was in the coal and lumber business. This father, like many fathers, gave his son a small plot for a garden of his very own - possibly the single most significant event of his life.

Years went by, with education in the local schools, until the age of only 18 the boy was catapulted into the German army, where he served from '14 to '18, seeing service both in France and on the Russian front. Schumacher commented, "When they thought I was minding the war business, I was really keeping my eyes open, everywhere I was sent, to see what they were growing and learn how they were growing it! I learned a lot. Oh boy, if they had only known!"

As soon as the war was over, Schumacher, who now knew that he wanted nothing more than to work with plants all of his life, enrolled in the Horticultural College of Berlin-Dahlem, where there was also a large botanical garden. At the College he specialized in dendrology. When he had completed his formal education, he worked in seedling nurseries in the District of Holstein and also in the tree and shrub department of the largest German nursery at that time, Louis Spaeth, near Berlin.

Postwar Germany did not have much to offer a young man with ambition. The only way to get into the United States was via an uncle in Oregon - a rather roundabout trip to the Arnold Arboretum! Schumacher said, "I knew there was a German at the Arboretum by the name of Prof. Alfred Rehder, so I wrote to him asking if there might be a place for me there. Rehder had just lost the Dutchman who was his foreman, so he tried me out and then offered me the position. That meant that I had to work just as hard as those Italians under me, and boy, oh boy, did they know how to work!"

Like many young men, he decided if he was going to have to work that hard, he might as well go into business for himself. So in the spring of '26, after about a year at the Arboretum, he opened a landscaping business in Jamaca Plain. In connection with this he started catering to the seed needs of nurserymen and foresters. "This sideline eventually became my principal occupation."

The seed "sideline" was in the basement of the business office. Aquarium supplies (the fund-raiser) were on the ground floor. "I was the first man who used the name 'The New England Aquarium,' and I did business under that name for thirty years." (The present New England Aquarium is a museum - no connection.)

"Every Sunday morning I would go to the Arnold Arboretum, where I was always learning something new."

Prof. Sargent and "Chinese" Wilson befriended the young immigrant. Prof. Rehder was his guiding start. His treatise on dendrology is still kept in the place of honor as a well-used Bible, thoroughly dog-eared from a lifetime of use.

"But I wanted growing grounds more favorable than around Boston. I had heard of a Mr. Dexter who was growing things very successfully on Cape Cod. So in 1940 I bought my Sandwich property from a Mrs. Martin."

It took Schumacher all of six years to move all of his plants from Norwood to Sandwich. His vegetable garden in Sandwich got him around the gas rationing, but nothing solved the dilemma of no weekend help. Picture him shuttling back and forth, "two

taxes

to a load!" By 1954 he had moved his entire business, including his office, to Sandwich.

The preoccupation with getting everything moved probably accounts for Schumacher never having met Dexter.

"Soon after Dexter's death in 1943, Mrs. Dexter sold the Quail Hollow part of the estate, where there was level land for nursery quarters, and where Dexter's latest crosses were lined out.

"Later the main property changed ownership four times before Mr. Lilly took over. Under the third owner, in partnership with a nurseryman on Long Island, the place was practically stripped of everything that could be moved. Whole truckloads went out to various destinations. There were local sales also, and I obtained a few plants. I do not remember the year: it must have been in the early fifties, probably 1952.

"It was under the fourth owner that Jack Cowles came in.

"Tony Consolini (who had been Dexter's head gardener for years) remained in service at the estate for some time, even in the employ of Dr. Brown, the first owner after Dexter. During Dexter's life, Tony had become quite confident. There was for a while even a contest going on between the two as to who would be most successful with crosses in which a tender parent was involved. It is unfortunate that neither Dexter nor Consolini kept records of their crosses.

"Mr. Peter Cook, new owner of Quail Hollow, sold Dexter plants, and I obtained a number from him, including

fortunei

x

haematodes

hybrids, from which I raised some outstanding early-blooming hybrids. These were from some of Dexter's latest crosses."

A good idea of the success of Schumacher's hybridizing may be gained from a reading of his seed catalogue. A much better idea may be had from a stroll on his "hill" when things are in bloom. Last May I was privileged to spend a full morning photographing some of the most vibrant reds I had ever seen, clear delicate pinks, luminous frilled whites. The entire Hill is "out of this world." No wonder the garden editor of one of the Boston papers wrote me, "Schumacher's Hills equals or surpasses any of the gardens in Europe!"

Schumacher says, "I merely took advantage of the opportunities offered by subjects that were blooming at the same time. A would-be hybridizer should start

early

in life, and have ample means to employ labor. It needs a man of means and leisure to do gardening at its best."

As to his actual techniques, Fred says he always tried to use the hardiest parent as seed parent, with the pollen from a less hardy variety. A small tray with glass custard cups, tweezers and plastic ties was kept at the ready during the blooming season. He would pinch off a stamen (or several) before fully ripe and put them in a glass cup. When the pollen was ready to fall off, he would hold up a stamen with the tweezers and touch it to the selected pistils until used up. Then he would use another stamen. He preferred this method to the artist's brush as the brush gets too sticky and wastes pollen.

Otherwise he followed the procedures described by Dave Leach in his book

(Rhododendrons of the World)

p. 404, with the exception that he never depended on labels. Instead he marked each cross with one or more plastic ties and recorded the full procedure on paper (like a stud book). "Wires wear out in windy weather and get lost, or are too much of a temptation for visitors to rip off." There are wooden markers in the ground by the results of the crosses.

As to raising seeds, Schumacher refers his customers to the "Woody Plant Seed Manual," prepared by the Forest Services: Miscellaneous Publication No. 654, obtainable from the Supt. of Documents, U. S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington 20025, D. C.

Schumacher reminds us that from harvesting to planting, seeds should be stored in an airtight container. It is absorbing moisture during a humid spell and giving it off during a dry one that dries out a seed and reduces its viability. There is no advantage to freezing. It is the temperatures just above freezing (32° to 45°) that contribute to the after-ripening process.

From 30 to 120 days are needed for after-ripening. When purchasing seed, it is safer to assume that the after ripening requirements have not been met, as the seeds have probably been kept too dry for this to occur. In nature, after-ripening requirements are usually met partly in the fall and partly in the spring. A cold pit will prolong the periods of low temperature ranges just above freezing, and is most conducive to the after-ripening process.

A trip through the Cooler of the F. W. Schumacher Co. is most impressive, with seeds upon seeds in glass containers as large as kegs. One looks in awe at this man through whose hands have probably passed more seeds than any single other human being, because of the nature and extent of his one-man seed business.

He says he has sold seeds to China, S. Africa, Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Russia, Mexico, Korea, Japan as well as many other countries. He has introduced seeds of many new and rare plants. Among them were the first seeds of the Exbury hybrids to be introduced in the United States.

All this while he was raising more and more batches of seeds, keeping only the hardiest of each generation.

For instance, his Loderi strain, from seed from Mr. Barber at Rothschild's, is the result of successive selection for hardiness.

Schumacher commented, "From the millions of plants grown by nurserymen from our rhododendron and azalea seeds, many choice varieties should have been encountered." Louise added, "We often had comments from customers that the seeds they were ordering represented crosses they would like to have made themselves."

Possibly his own favorite cross is one he calls "Our Best," ('Caractacus' x

fortunei

) x ('Britannia' x

fortunei

).

F. W. Schumacher, for all you have done to enrich our world, on your retirement we salute you!