Hunting for

New Guinea's Elusive Rhododendrons

Paul Kores, Wau Ecology Institute, Papua New Guinea

Last night I could see stars from horizon to horizon twinkling in the thin mountain air. I slept and during the night the cold came d own and touched the top of this mountain which has no name. It's dawn now and I sit holding a steaming cup of coffee while my breath drifts away in small white clouds. There is frost on the yellow-green flowers of Rhododendron pachycarpon which surround me. Soon it will be gone, for a hundred miles to the east the sun is rising over the saw-toothed peaks of the Saruwaged mountains. In Wantoat, a small village 8,000 feet below, it's still dark, but for me, at least, another long night in New Guinea is over.

|

|

R. pachycarpum

, Finisterr Mountains in Papua New Guinea

Photographed by Paul Kores |

|

|

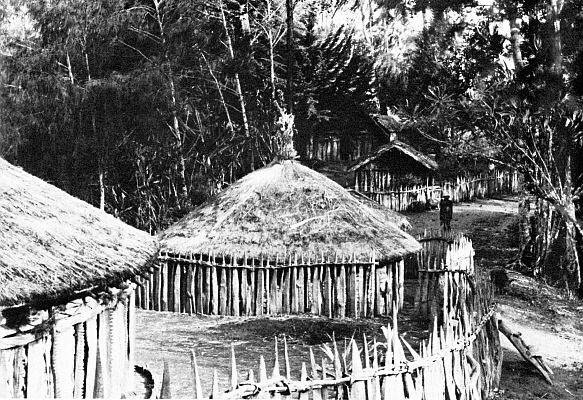

Typical highlands village in Papua New Guinea.

Photo by Paul Kores |

The island of New Guinea is shaped like an enormous bird 1,490 miles long, 450 miles wide and more than 3 miles high. Its 312,000 square miles of land have a reputation for containing some of the world's fastest rivers, steepest mountains and wildest jungles. Perhaps it is only fair that out of such remote and impenetrable places should come some of the world's loveliest rhododendrons.

There are approximately 160 species of rhododendrons known from New Guinea and this figure will probably increase as the remoter areas of the island are better collected. This represents about 20 per cent of the entire world's rhododendron flora confined to an equatorial island at the end of the Malaysian archipelago. All but two of these 160 species are endemic to New Guinea, occurring only upon this remote island. As a result, even today the rhododendrons of New Guinea remain the poorest known, least collected group of rhododendrons in all the world. They are one of New Guinea's most carefully guarded treasures for many grow where few plant hunters dare to tread.

Recognizing the fact that the rhododendrons of New Guinea represent a large group of ornamental plants with a tremendous horticultural potential about which relatively little is known, Dr. J. L. Gressitt, director of Wau Ecology Institute, acted on the advice of Dr. Pieter van Royen of Bishop Museum and applied for a grant to conduct horticultural research on the genus. This grant proposal was funded by the Stanley Smith Horticultural Trust in 1973 and I was brought to Papua New Guinea to begin work on the project in early 1974. That was almost four years ago and since my arrival in Papua New Guinea I've logged over 18,000 miles, by car, plane, ship and on foot. I've worn out six pairs of hiking boots and been rained on upon a dozen different peaks throughout the country.

The goals of this project are fairly simple; to collect poorly known species of rhododendron, identify the material I collect, prepare voucher specimens to be deposited in herbariums throughout the world, gather material for propagation and distribute this live plant material to institutions which have an interest in growing Vireya rhododendrons. So far I have managed to collect a little more than half of the 97 species of rhododendron reported to occur in Papua New Guinea. This includes two additional species not previously known from this half of the island, 14 new naturally occurring hybrids and at least one previously un-described species. Much of this material has been propagated and over 1,000 rooted and un-rooted cuttings have been distributed to institutions throughout the world. One immediate result of all this is that rhododendron enthusiasts may now have the opportunity to see one or more of seven species of Rhododendron not previously in cultivation without having to put on hiking boots and make along arduous trek up the jungle covered side of a 13,000 foot mountain somewhere in New Guinea.

Accomplishing all this within a three year period has been no easy task; plant hunting in PNG is not without its hazards. Papua New Guinea boasts of almost no paved roads, but thousands of miles of dirt tracks, accessible by four-wheel drive vehicles, twist and wind their way in and out of river gorges, over ridges and around the bases of the taller peaks. These roads are seldom wider than the distance between the left and right wheels of one's vehicle and may climb to as high as 9,000 feet. The view immediately below is usually spectacular, if one cares to watch. Looking over the edge of these roads it is not uncommon to see rocks dislodged by your passage bounce no more than twice before coming to rest a thousand feet below at the bottom of the river gorge you are driving through.

Drive these roads during the dry season and a haze of dust chokes you, return during the wet season and a sea of red mud smothers you. Progress is often no more than five miles an hour, but the route is always interesting. Open your car door, step into the knee deep ooze, wade to the road side and you can often find six species of rhododendron growing within arm's reach. Large, fragrant, white flowered

R. konori

, yellow flowered

R. zoelleri

and

R. macgregoriae

, pink flowered

R. dielsianum

and red flowered

R. inconspicuum

and

R. rarum

all growing as part of a multicolored tangle. Traveling along this country's byways and an occasional highway, though not in the American sense of the word, you can see about 30 different species of rhododendron. If this is not enough you had better be prepared to walk.

|

|

| R. atropurpureum , Mt. Wilhelm, 11,400 feet | R. stevensianum |

|

| R. christi Mt Bangeta, 10-11,00 feet |

|

| R. rubellum , Mt. Victoria |

|

| R. phaeochitum , Bulldog Road |

All photographed by Paul Kores in Papua New Guinea

Collecting high altitude rhododendrons in Papua New Guinea usually turns out to be a fairly involved process. Many species are only found within very limited geographic areas, or in some cases, may even be restricted to a single mountain top.

R. carrii

, a long, white, fragrant, Solenovireya and

R. spondylophyllum

, a small, bright, pink, Phaeovireya, are only known from Mt. Victoria.

R. comptum

var.

comptum

can only be collected on Mt. Albert-Edward,

R. solitarium

on Mt. Kaindi,

R. tuba

on Mt. Dayman and

R. hellwigii

on Mt. Bangeta. All of these species bloom at different times of the year and many of them are almost impossible to identify when not in flower. Once they finish flowering, the plants blend back into the sea of green which covers the mountain sides becoming all but invisible to would-be collectors. This is in addition to bad weather which can leave you stranded for days at a time. Aircraft, your only link with the outside world, arrive days early, or more often, never appear at all. Mysterious rivers not marked on your map bar your way. Hordes of biting flies, chiggers and leeches follow you everywhere, or worst of all, after three grueling days of hiking you find yourself standing on top of the wrong mountain. Fortunately this usually doesn't all happen on the same trip.

One particular trip comes to mind when I think of all the catastrophes awaiting would-be plant collectors in PNG. I had been asked by the Australian Rhododendron Society to try and collect some material of

R. hellwigii

, a very large, red flowered species, only known from the Mt. Saruwaged - Mt. Bangeta area. I made the necessary arrangements for our departure and chartered a small, single-engine aircraft to fly our party to an airstrip nestled at the base of Mt. Bangeta. The place was called Derim and the small grass runway looked so short from the air I think a good golfer could have hit a ball the length of it with a putter. Fortunately the runway was rather steeply pitched and all landings were done uphill. We made several circuits of the area dodging clouds, trees and the roofs of some of the ridge top villages, finally touching down before a crowd of almost 200 local residents. After a rather rigorous 25 minutes of handshaking interspersed with top level negotiations, I managed to employ 14 men to transport our supplies and extracted myself from our reception committee.

We left Derim at dawn the next morning with over 400 pounds of provisions of what was to prove to be the beginning of a very strenuous three-day walk. The first day we covered a distance of no more than six miles according to the map I was carrying, stopping for the night in a small village called Kontrone. Curiously enough, neither Kontrone nor the convoluted trail that leads to it were marked on my map. I suspect some surveyor stood on the brink of the Timbe river gorge 2 miles from Derim and eyed the trail as it wound down into the mist. He listened to the tortured sound of water being squeezed through a narrow rock channel a thousand feet below, looked over the mist, saw a thin brown line staggering up the far side of the gorge and in his mind Kontrone and the trail leading to it ceased to exist. It took six hours to cross that river and climb the ridges that lay between us and Kontrone and it wasn't until last light when we finally reached our destination.

Kontrone was a small village by New Guinea standards with only about a dozen houses perched on the only flat piece of ground between Derim and the top of Mt. Bangeta. Its people were friendly and quickly offered us the house in the village reserved for government officials and honored guests, both rare commodities in a village far away from the government headquarters for the region and difficult to get to. Our quarters for the night were tiny and constructed with the same flare for architecture as the rest of the village. The house was constructed of bark walls topped off by a foot-thick thatch roof, a floor of woven grass mats and a single raised sleeping platform made of split palm slats. There were no windows and the only ventilation was provided by the down draft of refrigerated air which flowed off the slopes of Mt. Bangeta and seeped in between the rough wooden planks that barred the small doorway after dark. In the center of the floor, space was left for a fire and the shallow depression in the ground was filled to overflowing with ashes. Above the fire pit the roof and rafters were stained so black from the smoke of countless fires the wood glistened like polished ebony. The low thick roof, stout walls, small doorway and huge pile of ashes in the hearth all testified that the nights in Kontrone are often long and cold.

|

|

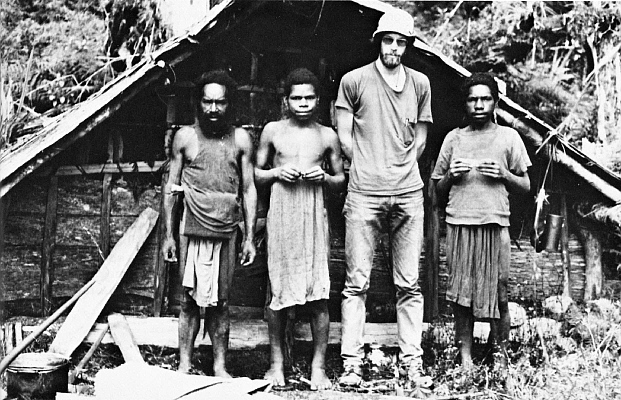

One of the night camps on Mt. Giluwe with local guides standing on either side of Paul Kores.

Photo by Paul Kores |

We had several guests after dinner, village elders, councilmen and people who were just plain curious as to why a white man would want to come and look at their mountain. I told them of my work and some people shook their heads and walked away, sure that I was crazy. The rest stayed and as we drank tea we made arrangements for people to carry my supplies up the mountain. I was told all the men in the village were far away working on a new airstrip and that I would have to use mostly women to transport my cargo. They told me the road was no good, the way long and difficult and it was the wrong time of the year to visit the mountain. August was the time when the big rains came and the tops of the mountains were often covered with ice. This all sounded a bit ludicrous to me and I told the villagers so. Mountain tops covered with ice meant glaciers to me and although there are a few glaciers in West Irian the mountains in PNG are lower and there is no ice on them. It wasn't until later I realized my mistake.

I finally made arrangements for twelve women and two men to transport my supplies up the mountain. It was to be a long day tomorrow and we all agreed to get as early a start as possible and next morning. I bid goodnight to the elders and councilmen, chased out the "hangers-on" and went to bed. I remember snatches of that night; people huddled around a flickering fire telling stories as their shadows danced upon the gray bark walls, songs sung in a local "tok ples" I could not follow, clouds of smoke that rolled around the room like fog, dogs barking and the intermittent snores of some lucky fellow completely oblivious to his surroundings. Finally the cocks started crowing, though dawn was still an hour away, but for us the night ended abruptly. The door to our house flew open and without a word a host of people poured into the dimly lit interior. Pots, pans, blankets, camping gear, food supplies and personal affects were snatched up by women in grass skirts. People shoved and pushed one another around, arguments erupted and fights broke out. I was literally dumped out of my sleeping bag and left to watch the whole process in a state of utter confusion as the entire contents of our house was removed in less than ten minutes. My first thought was that we had been attacked and our equipment stolen. It wasn't until things settled down and the troop of visitors lined up outside the door with their loads neatly packed, that I realized our carriers had arrived and wished to make good their promise of an early departure.

Unfortunately, our carriers had been so thorough at packing my belongings that virtually everything I owned was stuffed safely in someone's string bag awaiting me outside; including my eyeglasses and more importantly, my trousers. This was an extremely awkward situation as I had no intention whatsoever of storming out in front of an entire village, clad only in my underwear, and demanding my trousers. I did have a local assistant with me at the time, who was fully dressed owing to the fact that he had been in this type of situation before and had wisely chosen to sleep in his clothes. I explained my difficulty to him and sent him out to do my bidding. I shall never forget my reaction, nor the period of dead silence that followed, when he went outside and asked in aloud clear voice that carried throughout the entire village; "Trausis bilong masta i stap long wanem pies?" (Which means; where are the boss' pants?) Fifteen minutes later, amid smothered giggling fourteen carriers, two assistants and one very red-faced master started up Mt. Bangeta.

The track leading out of Kontrone plunged into thick forest above the village and wound steeply uphill. The going was very difficult and for the next six hours we climbed at a rate of a thousand feet per hour. Rhododendrons began to become more common as we gained altitude, at first appearing as epiphytes rooted in the moss filled crotches of the larger trees. Fallen corollas littered the trail everywhere and before too long these flowers found their way into the hair of many of the women who were carrying for our party.

Rhododendron christi

with its two-tone, red and yellow flowers,

R. herzogii

a fragrant, white species with long, tubular flowers and the blood-red blossoms of

R. hellwigii

were all common along our route. I collected ten different species of Rhododendron on that day's walk, which would have been a more than sufficient reward for my efforts, but, Mt. Bangeta had even more to offer. The alpine grasslands which started at 12,000 feet contributed an additional four species of Rhododendron to my collection.

We slept in a small cave cut into the side of a limestone cliff at 12,800 feet that night. The place was used frequently by hunting parties who came up to the grasslands in search of game and was even partially furnished when we arrived. The furnishings, an old torn blanket and a small bag of food, were left by the cave's last occupant. I inquired about this and was told by our guide; "Kol i kisim dispela man na en i dai pinis." The poor fellow who had owned the blanket, had run into some bad weather on the occasion of his last visit and died of exposure. His belongings were left as a reminder to future travelers and it was not until the dead man's possessions were removed and a small pile of food left to placate his ghost, that our party would move in. That night the wind howled and the rain poured down, but we were snug and dry and I never gave the terrible weather outside a thought. The next morning one of our guides went outside; returned, walked over to me as I wrote my field notes and as I looked up, dumped a huge pile of snow in my lap. I looked at the white mass in my lap with disbelief and as I stared the guide calmly stated, "Ais i pundaun." It was then and there that I remembered that the villagers had told me before we set out. When they warned me about ice, or "Ais" as they call it, they weren't talking about glaciers; "Ais" in pidgin English is the word for snow. It was two days before we could move out of that cave and start down off the mountain.

It has been three years since I climbed Mt. Bangeta and I have been told by the people at Edinburgh that the

R. hellwigii

I sent them is doing well. I have climbed another half a dozen mountains since then and sometimes when it's been raining for the past five days and everything I own is soaked, or the roof starts leaking on me at 3 am, or I sit down to my fourteenth consecutive meal of tinned bully-beef and rice, I wonder if there aren't easier ways of earning a living. But, then those other people have never seen the alpine grasslands in the sunshine, or collected a rhododendron no one else has seen in the last 50 years, or found a new species entirely unknown to science. So I guess things tend to even out and I'll continue to hunt for New Guinea's elusive rhododendrons for awhile longer.