Transplanting Native Azaleas and Their Propagation by Root Cuttings

Fred C. Galle, Pine Mountain, GA

For more than twenty-five years, in developing Callaway Gardens, we have collected many thousand native azaleas, both from our own properties and from land which was being cleared for development, in the general area and even some outside the state. We have had the opportunity, also, to check on many of the native azaleas, which have been collected by plant hunters, and find that results from transplanting have been very poor. It has been our observation and experience that many of the collected azaleas have been brought in with very sparse root systems, often resulting in dead plants within the first year. Thus, the comment that we are constantly hearing is that they are very hard to transplant.

|

|

Multiple stemmed

Rhododendron speciosum

8-10' plant, dug with 6' ball |

|

|

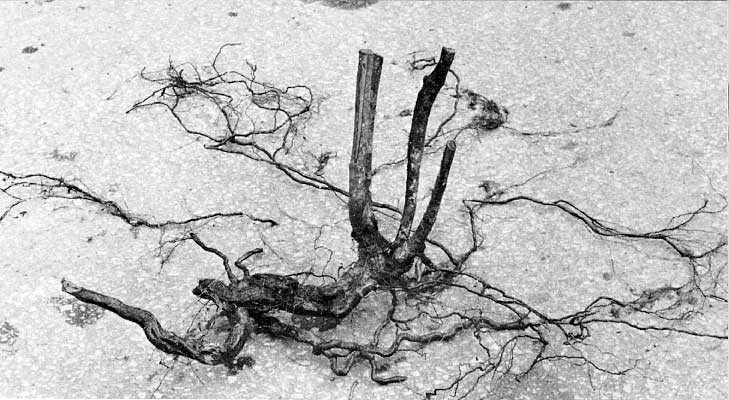

Rhododendron speciosum

plant showing root system from the 6' ball.

It is estimated that only 40% of the root system was obtained from this large ball. |

To answer some of the problems, we can share some of our experiences with the collection and replanting of these beautiful species. Several years ago, when we were transplanting some plants owned by a timber company, I brought in a large, multiple-trunked Oconee azalea, Rhododendron speciosum , about 8-10' high, with several stems of one to one and one-half inches in diameter. We dug a root ball of 6', shown in the photograph. The ball seemed a mass of roots, but upon washing it, noted that we had only one-third of the azalea root system from the original site. The root mass often thought to be azaleas was from surrounding plants. This is not always the case. In some soils, you may get more roots, but, basically, it has been our experience that we were getting very little of the azalea root system. If we had dug the conventional two-foot ball, we could have had less than one-third of the root system. It was also our experience that we needed to compensate for this poor root system, by doing some drastic pruning of the top of the plant. Our experience, for more than twenty years, has been to cut the original plant back within six inches of the ground. The plants are heeled-in in ground pine bark, kept well watered and held for one season. They are fertilized several times during the season with 10-6-4 or higher analysis, using a nitrogen of the urea formaldehyde form. The main point is to keep plants watered during this first season. At the end of this season, these plants have developed a completely new root system. New adventitious shoots have also developed to produce a new branching compact plant. We frequently have flower buds developing the first or second season. We have been successful in moving plants in this way almost every month of the year. Perhaps some gardeners feel it unnecessary to cut back when transplanting in winter or very early spring; we still advise it for collected plants. I have recently learned that some azalea collectors, in an effort to avoid cutting back their plants, keep the collected plants under a mist system. We have not tried this same method. However, many years ago, we retained a group of collected azaleas in a lath house in specially prepared soil and the results were far from favorable. Occasionally, we find, one-year cut back plants under power lines or on railroad rights of way. These plants move with better success, but they still have to regenerate a new root system.

|

|

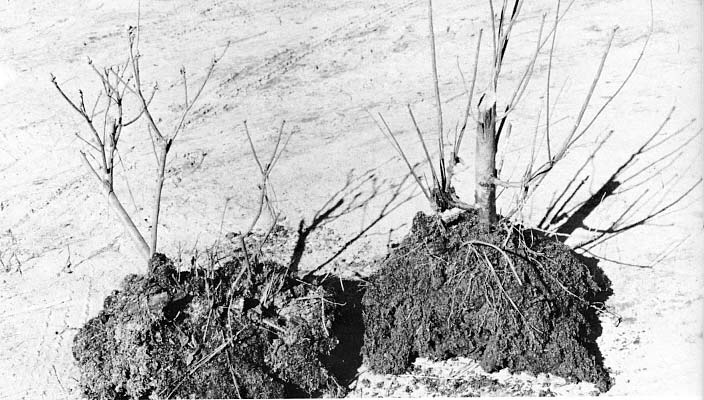

Two plants of

Rhododendron canescens

, showing fibrous root systems

developed in one growing season. The plants were cut back and heeled-in using a bark compost mix. |

The photograph shows a cutback plant of

Rhododendron canescens

, with the type of root system which is formed using this method. Also, along this same line of thought, we were concerned about areas where we had the opportunity to collect large numbers of plants, concern that we might be denuding the areas of native azaleas, but this did not prove to be the case. In fact, when going back to the same area three to five years later, we found more young plants than ever before, provided the land had not been cleared for cultivation or stripped of its top soil. We found many root pieces left in the ground developed new adventitious shoots and grew into new plants. Following this observation, we tried root cuttings many years ago and found that all native azaleas could be propagated by this method. It is true that the stoloniferous species and plants tending to be stoloniferous are easy to propagate by this technique. This method consists of using root pieces of 3-4' in length, about the size of a pencil, ¼" to ½" in diameter, which can be taken even as you are digging the azalea. Make sure, of course, that the roots do not dry out while returning from your collecting trip. We transport them in plastic bags with a little sphagnum moss or damp leaf mold. Upon arrival the root pieces are laid horizontally onto damp sphagnum moss and covered lightly with the same. We have had the opportunity to take root cuttings in the early spring and into mid summer with success. This method does offer possibilities of reproducing some of the very strikingly beautiful forms when there is an opportunity to dig the plant and when it cannot be increased by rooting stem cuttings. Many native azaleas are difficult to propagate from stem cuttings, particularly the non-stoloniferous ones. Thus, this method of propagation by root cutting offers another way of increasing these beautiful plants.

The root cutting procedure has merit. We have used the same methods in propagating other native plants, viz.,

Aesculus parviflora

, the bottlebrush buckeye;

Elliottia racemosa

; and several species of the sumac,

Rhus

sp. This method might be tried with success on other plants as well.