Our Wild Eastern Treasures Native Azaleas

Martha Prince, Locust Valley, NY

Reprinted from American Horticulturist

All Photos by Author

The most joyous imaginable first introduction of a city gardener to a wild azalea would take place on a June day in the lovely mountains of western North Carolina. The azalea would be the Flame (

Rhododendron calendulaceum

), reigning monarch of our native eastern species. "Calendula" means marigold, and the name fits well. Colors vary from palest yellows through sun-bright oranges to firecracker red. For such an introduction, Nature provides, as background, a celebration of color. The Catawba Rhododendron (

R. catawbiense

) is in full display - pale pinks, soft lavenders, magenta. The Mountain Laurel (

Kalmia latifolia

) parades its intricate buds and flowers in pure white, in the usual calico, and in red-bud forms worthy of selective propagation. On grey rock ledges, clumps of blazing Fire Pink (

Silene virginica

) look down on yellow heads of Evening Primrose (

Oenothera biennis

), creamy plumes of Goatsbeard (

Aruncus dioicus)

and the peculiar pink of Beardtongue (

Penstemon canescens

). As an artist, Nature here splashes colors with an abandon and a gaiety quiet alien to the small garden. Her background, however, is the soft and endless blue of the jumbled mountains. As painter, Nature heralded Miro and Matisse.

Our city gardener, meeting a native azalea for the first time in such a setting, could but come away bedazzled. I know. I, myself, grew up in azalea-country, but I have a city-bred Yankee husband. He was already a member of the American Rhododendron Society, and a knowledgeable gardener, when I first showed him the Flame azalea at-home-in-them mountains. His reaction was a simple, unbelieving "Wow." Nature provides no equivalent spectacle anywhere else in our eastern American wild land.

What are our native azaleas? All azaleas are of the genus

Rhododendron

;

Hortus III

lists them as a subgenus, Pentanthera. In standard reference books on azaleas you will find subgenus Anthodendron instead, or (simplest for the non-botanist) just series Azalea. All are members of the Heath family (Ericaceae), and as such are cousins of multitudes of plants from blueberries to Trailing Arbutus. The subgenus, or series, is next divided into sections (

Hortus III

), or subseries; we have representatives of two. Both are deciduous. They are quite distinct, and a gardener need not be a botanist to see the difference. The smaller of the two groups is section Rhodora (

Hortus III

), listed in most books as section or subseries

Canadense

. These flowers have the five petals of all azaleas, but the upper three are grouped together; there is little or no corolla tube, and the stamens number seven or ten. The larger group is called Section

Pentanthera

(the same as its subgenus) in

Hortus III

, but you will find it more often as subseries Luteum. Here are five quite separate petals or lobes (the upper one often wider, blotched, and sometimes ruffled), the corolla tube is long and definite, and the stamens number five.

At this point comes the further division into species; at this point, also the taxonomists begin arguing! America has seventeen species, or fifteen, or sixteen. "Someday these will be further divided," or, "Someday these will be further grouped." What is really important to grasp is that our azaleas form a shifting, hybridizing population, the shift going far back in time, yet continuing today. The bees have been promiscuous too often for any neat and permanent taxonomy. Sometimes a species has been listed as valid, then dismissed (for example, David Leach proved quite conclusively that a lovely pink called furbushii was a recent hybrid). No matter what I write, I am sure to be questioned!

All but one of our species are eastern; I will write only of these for they are the ones I know. Together, these azaleas give us woodland treasures from Maine to northern Florida, varying in color, in fragrance, in growth habit, in blooming time. No one botanist, no one flower lover, could adequately explore them all in a lifetime.

I present the azaleas in a simplified arrangement, of necessity. Most writers group them by color, or by blooming time, or by geography. Each of these approaches can be confusing. Under a "Pink" you may note, "One of the best forms for the garden is white." Blooming time depends on locality. A geographical listing stating that

R. prunifolium

is a native of a very small area in midwest Georgia and mid east Alabama" might lead one to believe a New York gardener should ignore it. (Plants of

R. prunifolium

survived the brutal northern winter of 1976-77 with flower buds bravely intact.) I will merely list them alphabetically, under the two subseries, or section, groupings. Also, I do not adhere rigidly to

Hortus III

. I discussed this with Dr. Henry Skinner, the very knowledgeable former Director of our National Arboretum. He agreed that some nomenclature as used could be confusing. Name changes will take a long, long time to filter into the vocabularies of most gardeners...by them, it may be time for a new

Hortus

, and a new language. I know that I, at least, cannot suddenly call an old friend by a different name!

I begin with the smaller, and less familiar-looking, section

Rhodora

(or subseries

Canadense

). The nearest relatives of these azaleas are Japanese.

|

| R. canadense |

R. canadense is the Rhodora of New England poets. Emerson's words, "Beauty is its own excuse for being" were written about this small and much loved little flower. Some may call it scraggly, and even of poor color (the range is from a pale pinkist lavender to deeper shades of almost magenta; there is also a lovely white). If you find it nestled in the crevices of grey granite, along Maine's coast, or filling a bog between the dark spruce trees, you can only call it perfect. It is low (as low as one foot in height in windswept spots, or three in bogs, twiggy, and the distinctive grey-green of the leaves comes after the flowers. The three upper petals are only separate at the very tips, and are speckled in a darker color. In Maine, the bloom time is the first week of June. The natural habitat extends down to New Jersey. In a Long Island garden, where it is not native, I have found an approximate date of one month earlier.

|

|

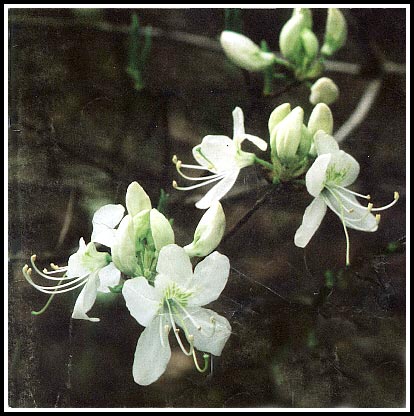

R. vaseyi

Photo by Martha Prince |

|

|

R. vaseyi

, 'White Find'

Photo by Martha Prince |

R. vaseyi

is known in its North Carolina home as the Pinkshell Azalea. Years ago it was not considered an azalea at all, but had a genus name of its own,

Biltia

(long invalid). As with its northern cousin, the upper three petals are grouped, but not tightly so, and both species have no corolla tube. Whereas the Rhodora has ten stamens, Pinkshell has seven. Color? A good soft pink with a hint of green in the throat and a sprinkling of paprika-red dots at the base of the upper petals. An excellent cultivar is 'White Find' - the dots being green on snowy petals. One peculiarity of

R. vaseyi

is that it does not hybridize. It blooms at about the same time at home in its mountains or in a New York garden - May 1.

Next, we turn to section

Pentanthera

(or, subseries

Luteum

), which is the larger grouping and much more familiar to us as "looking like azaleas". The species

R. luteum

itself comes from near the Black Sea, another species comes from China, and another from Japan. The vagaries of botanical geography are fascinating! What a history of the physical world could be told by the distribution of plant life...the spreading and receding of the glaciers, perhaps the drift of continents.

|

| R. alabamense |

R. alabamense is a rare little azalea, pure white with a yellow blotch in the typical form. Alabama Azalea is its only common name. In its very localized home (part of Alabama and west central Georgia) it perfumes the air with a really delightful lemon scent. It is a stoloniferous plant, and spreads over the low hills. As with most whites, some forms are pink tinged, probably from living too near R. canescens , so bees could exchange pollen. In Alabama, it blooms about May 10. My bloom dates for Long Island are nearer the 20th. Plants here bloomed well after a rough winter.

|

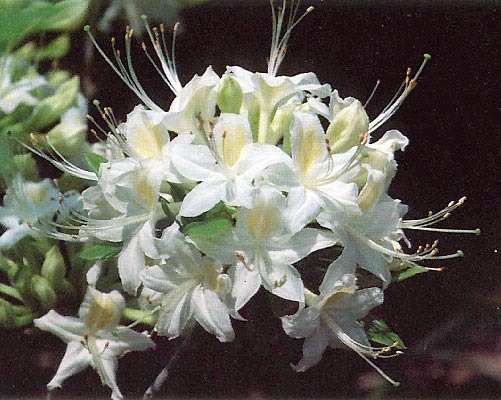

| R. arborescens |

R. arborescens

is the Sweet Azalea, and sweet it is. Books insist on calling the fragrance "heliotrope", but I, for one, have never smelled heliotrope. The flowers are very star-like in form, and the white is accented by a red style. Often all the filaments are pink, and sometimes the corolla tube and the bud tips. In hybridizing it "throws pink", as they say. I have been sent a photograph of a good clear pink flower, but I have not actually seen it. My favorite plants are a group of pink-tube ones, with very large flowers, growing in the Nantahala Mountains of North Carolina. In height,

R. arborescens

is medium to tall. Locale? Georgia all the way to Pennsylvania, at least. I have photographed North Carolina mountain blossoms on June 20, and Long Island garden ones during the first three weeks of July.

R. atlanticum

, called the Coastal Azalea, is another white-which-is-sometimes-quite-pink. It is coastal, going all the way up from South Carolina to New Jersey.

R. atlanticum

is aggressively stoloniferous, and one plant can grow to cover a huge area. As a very low azalea, it could be used to advantage in facing down woodland areas in gardens, but it has not been much planted. In South Carolina, it blooms about the end of April; Long Island dates are not much later, - early to mid May.

|

| R. austrinum |

R. austrinum

is known as the Florida Azalea, although it grows all the way to Mississippi, near the Gulf Coast. This is a lovely yellow-blooming shrub, and one of the early signs of a bright spring in the South. The flowers are not large, but are very showy, indeed. Often pure yellow, it also has forms with red corolla tubes, which are even more gay. At "home," its blooming companions, in late March, are the pink and white forms of

R. canescens

. The garden photographs I have taken on Long Island have been in mid-May; unhappily, the plants I know here died in the bad winter of 1976-77.

R. bakeri

is also called the Cumberland Azalea. It is usually red, and is one of the most recently classified. The name was first given to plants found near Wolfpen Gap in the Georgia mountains; the area is only about thirty bird-flight miles from my home in Georgia, in a place I frequented as a child. I must have assumed, as did everyone else, that the bright azaleas were Flame. The colors are at the redder end of the Flame spectrum, but they vary. Also, they hybridize much more freely; there are many fine pinks which the bees bequeathed us.

R. bakeri

is, in general, a lower plant, stoloniferous, and later-blooming. The really positive identification is by microscope;

R. bakeri

has the normal number of chromosomes, and the Flame Azalea has a double set. Blooming time? At Wolfpen Gap, and on into the 3000 foot areas in North Carolina, approximately June 15; at one of the most glorious areas, Gregory Bald in the Great Smokies, July 1. The azalea grows into Tennessee and Kentucky. In Long Island gardens, it blooms at about the same time, sometimes saving its burst of firecrackers for July Fourth.

|

| R. calendulaceum |

R. calendulaceum has to be the queen of them all. Are you familiar with the color fans of the Royal Horticultural Society? If you are, open the red-yellow fan to show the full range of colors from number 11 to number 44. The array is truly astonishing! I recently had to testify before the United States Forest Service in Washington, against clear-cut lumbering of a large area of the Nantahala Mountains; one of my "exhibits" was the opened fan. I have color catalogued as many as thirty-five distinctly different R. calendulaceum in two days, in those mountains. I began this article with a "poem" to my favorite flower; I will add no more adjectives. The Flame Azalea is a tall plant (up to fifteen feet.) Botanically,, the most interesting feature is that it is the only one of our eastern azaleas in the Luteum subseries which is tetraploid. That means there are twice the usual number of chromosomes; as chromosomes come in pairs (and the azalea number is 13), 2N = 52. This accounts for the variety; the genetic "pool" is enormous. Until recently it had been thought that R. calendulaceum had two separate "phases". One group was low-elevation, early-blooming, and larger. A recent study in depth by Dr. Frank Willingham seems to have proved this theory incorrect. His study found all botanical characteristics randomly distributed, whether the azalea grew high in the mountains, or lower. At 5000 feet to 6000 feet in North Carolina, the bloom is best at about June 20, and on Long Island it is the same. The Cherokee Indians had a wonderful name for the Flame Azalea, "Sky Paint Flower." William Bartram called it "the most gay and brilliant flowering shrub yet known.

|

| R. canescens |

R. canescens

(the Piedmont Azalea) is probably the most abundant of all our azaleas. Masses of its pink blossoms grow all over the lower South, from Georgia, upper Florida, west to eastern Texas. A typical flower is a deep pink in its tube color, and pale pink in the petals or lobes.

R. canescens

is an early bloomer; you will find it by about March 20 in its southernmost home. On Long Island, a garden plant may be at its best around May 5 to 10.

R. nudiflorum

(the Pinxterbloom, or "pink honeysuckle" to the farmers), has had a name-change decreed by

Hortus III

. It has been decided that Michaux's

periclymenoides

takes precedence. The problem is that this does not appear even as a synonym elsewhere. Bartram used

A. nuda

. By any name, however, it is a lovely plant. In appearance it is quite similar to

R. canescens

, but a more northern counterpart. It can be found in white (as can

R. canescens

), and Dr. Skinner once reported a purple one with a yellow blotch. Plants grow as far north as New England. On Long Island it is native, although it is hard to find nowadays. I have bloom-dates on it here from May 5 (on some photographs) to May 20 (Planting Fields Arboretum).

R. oblongifolium

(the Texas Azalea), is an inconspicuous white, so similar to

R. viscosum

that some taxonomists would argue its inclusion. It grows in its name-state, in Arkansas, even in Oklahoma, and blooms in June.

|

| R. prunifolium |

R. prunifolium , called the Plumleaf Azalea, is a rare treasure from a tiny area on the Central Georgia-Alabama border. The plant is very handsome, with the leaves fully opened when the blossoms are. The red flowers resemble those of R. bakeri in many ways, but it is a very late bloomer. Around Fort Gaines, Georgia, different plants may spread the flowering season all the way from the end of June until the first of October. I have photographed some garden plants here on Long Island on July Fourth - bright fireworks for the celebration. Planting Fields has listed their bloom-dates for me at August 1 to 15.

|

| R. roseum |

R. roseum

, the lovely Roseshell Azalea growing from Virginia northward, has been demoted by

Hortus III

to a variety of

R. periclymenoides

. I am afraid I will go right on calling it

R. roseum

! It is pink, too, but has a shorter corolla tube (and wider). It has not only been demoted, but an earlier name now takes precedence; correctly, it is now R. periclymenoides var. prinophyllum. In range, it blooms from Virginia west to Ohio and Illinois, and all the way north to southern Quebec. The new classification presents

Hortus III

with one botanical difficulty; I will explain what glandular means when I finish this listing; as of now the description of the former

R. nudiflorum

has to say "Tubes variably glandular".

R. nudiflorum

, as we previously knew it, was not glandular;

R. roseum

was (and

R. periclymenoides

var.

prinophyllum

is). Do I sound unduly upset? I am! I almost feel I am defending a very beautiful friend against an army of taxonomists. Whatever its name, the flowers are at their lovely best here on Long Island (it is not native) about the first of June.

R. serrulatum

is also called Hammocksweet, and is another southerner. It is a white, with a very long corolla tube and small flowers. In range, it grows from the palmetto country of mid-Florida, up through the Sea Island area of coastal Georgia, and westward to southern Mississippi. The virtue, to gardeners, is the lateness of the flowering; an average blooming date in its native area would be mid-July. I have a friend who grows a late form en masse with a late form of

R. prunifolium

, for his last azalea display. Here on Long Island, my photos are dated August 15. Unhappily, the plant proved unable to cope with the winter of 1976-77.

|

| R. speciosum |

R. speciosum

, the Oconee Azalea, is another victim of name-change.

Hortus III

gives precedence to Michaux's

flammeum

. Michaux discovered the plant on the Savannah River (1787), and his name for it is at least given as a synonym in most available reference books; this "new" name will thus probably be easy for us to use. The colors of

R. speciosum

are similar to

R. calendulaceum

. The range, however, is very restricted - part of central Georgia and down along the river. In its native area, the flowers should open by May 1. On Long Island, the blooms appear nearer the 20th; I have photographed it here, but it is not reliably hardy.

R. viscosum

(Swamp Azalea) is a white, fragrant azalea which seems to grow anywhere. It can be found from Maine to Georgia (and from mountain top to bog). Although the flowers are not conspicuous, a warm summer sun on a massed planting of them brings a pleasant spiciness to the air. The petals are so sticky (glandular) that they are unpleasant to touch. Boggy areas near the shore on Long Island are full of them...but so are mountain tops in North Carolina. On Long Island, the bloom-date is late July.

As you notice, I have used little in the way of botanical terminology; there is just one "clue" used in botanical "keys" which I recommend all gardeners learn, for the sheer pleasure of it. Keys will say that the corolla tube is "glandular" or "eglandular". Glands are little round pinheads on the ends of setae, or hairs. The glands give the stickiness to the

R. viscosum

, which I just discussed. How to see them? A x 8 flat-surfaced little hand magnifier is my accompanist in the field; a good one should not cost more than ten dollars, and will give you much pleasure, and a new look at the world of flowers. The glands on

R. serrulatum

are glistening diamonds on the tips of icicles; on

R. calendulaceum

you may find that the glands are rubies. Of what practical use is this: If you are in North Carolina in early May, and find a pink azalea, first decide if it fits into the

Luteum

or

Canadense

subseries. If

Luteum

, there are only two choices if there are glands, the flower is

R. roseum

(with apologies to

Hortus III

.) If there are no glands, you have

R. nudiflorum

(

R. periclymenoides

). These are hairs, yes, but they rather resemble a pink fur coat when I project a close-up slide on the screen!

If you want to grow these charmers, whether you plan a wild garden or want a few specimens, you will be happily rewarded. I have seen

R. calendulaceum

and

R. nudiflorum

doing well in a Maine garden beside the native Rhodora. New York is just about borderline for including all, but it can be done, with protection for some. However, if hardiness is wanted, leave out

R. austrinum

,

R. speciosum

, and

R. canescens

; established plants of these species did not survive in 1976-77. There would also be little point in trying

R. serrulatum

or

R. oblongifolium

when the native

R. viscosum

, which is similar, does so well. If your garden lies much to the south of New York, forget Rhodora, but begin adding the others. A Virginia garden should have virtually unlimited choice (except for Rhodora). If you live in southern Georgia, you have lovely local species, which would make a beautiful garden even without any others. In Florida, the farther south you are the more you must omit...in southern Florida I would not even try

R. austrinum

, but would settle for

R. serrulatum

alone.

If you are presently growing any of the deciduous hybrids (Exbury, Knaphill, et cetera) you are already growing descendants of our native wildlings. American azaleas can shine as brilliantly as their titled offspring! All are acid-loving plants, doing best in the same conditions you would choose for any azaleas. Dappled shade, a pH of 5 to 6, humus-rich soil, moisture but good drainage, satisfy most requirements. Some seem more "fussy" than others (

R. prunifolium

for instance, but

R. viscosum

will tolerate practically anything.

I admit to loving our native azaleas with what amounts to a passion. My husband and I go south every June to photograph and study the Flame Azaleas; we head north (to Maine) at the beginning of the same month for the sole purpose of photographing Rhodora. Last summer, Maine was in a sodden week of rain and fog. We are stubborn photographers, however. My husband held my red slicker over the camera while I took pictures. I got wet - he, camera, and flowers fared beautifully. In North Carolina, I have been atop a slippery steep bank, only to be hailed by a ranger, "What the hell are you doing up there, lady?"

We enjoy it all - the scenery, the adventures, the learning. I am sure equal joy awaits flower adventurers on other quests, but we still chase William Bartram"s "'fiery azalea". We will never find the ones he first saw, by the way. "Progress" encroaches on everything; the plants bearing the flaming blossoms about which he was so ecstatic vanished deep beneath the water of the Clark Hill Reservoir, near Elberton, Georgia. We must find our own!

I hope I have shared some of my pleasure with you. If so - "Bon Voyage". An azalea quest is a never ending one.