Victoria: The Old And The New ARS Convention 1989

Leslie and Frank Drew

Duncan, British Columbia, Canada

About the time that the first great species rhododendrons of southeast Asia began reaching the western world in dramatic numbers, Victoria on Canada's west coast was starting life as a far outpost of British commerce. The newly-discovered plants exciting botanists in the British Isles were furthest from the thoughts of the rough-and-ready men of the fur trade. Most of them would not have known the word Rhododendron , let alone have met one in broad daylight; they had more important matters at hand in a vast untamed country that was not yet unified. The genus and the place went their own ways, diversifying, hybridizing, expanding. Now, 140 years later, the two will come together formally at the American Rhododendron Society's 1989 convention in Victoria, British Columbia, April, 26-30.

|

Today, Victoria is a cosmopolitan place with a population in and around of close on 300,000. Ranch style homes sit congenially next to turreted stone and timber mansions. Thoroughly modern public buildings of steel and glass stand quite comfortably next to ornamented granite and brick edifices that are almost a hundred years old.

Victoria's Conference Centre is so new that it will virtually open its doors for the ARS convention. This $23 million glass-walled structure is located right by the Empress Hotel, symbol of the Canadian heyday of luxury rail and ocean liner travel. Nothing much is done in haste in Victoria, so when the time came for a convention centre, it had to fit appropriately.

Queen Victoria's city is, after all, a very proper place, sedate and conservative. It looks rather like an English provincial town except that the scenery is splendidly different. In full view, across the blue waters of Juan de Fuca Strait, rise the Olympic Mountains and snow-domed Mount Baker, both in Washington state. Naturally this was a choice setting for a jewel in the imperial crown of the British Empire.

Almost from the start, Victoria has been a favored, if not pampered, city. It is perhaps the only major city in western Canada to have gone from log-cabin hardware to computer software without so much as a whiff of heavy industry in the intervening years. (At last count 110 technology-based companies operate in and around Victoria.)

Victoria's History

History as casting director gave Victoria a special role. The little Hudson's Bay Company trading post of Fort Victoria developed into a base for government, first of the Colony of Vancouver Island, a land mass not much smaller than Connecticut and Massachusetts combined, and in 1871 capital of the newly-created province of British Columbia.

Vancouver on the mainland, a more populous city today, did not exist then. Politicians from the mainland have always been bothered by the fact that the seat of provincial rule should be offshore, but for Victoria it was an act of grace. As everybody knows, governments however tight-fisted tend to spend public funds more freely on their capitals than on ordinary cities. Victoria could settle down to making herself beautiful, and this she did.

Victoria prospered, apart from a blip or two, in the thirty-year period from the 1880s into the First World War. Development of steam transportation was the main factor. Completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, uniting the country from Atlantic to Pacific, brought people as settlers in unprecedented numbers. Tied with ocean liners, the railway was part of an Empire-circling commercial network stretching to the Orient, Australia, India, and Africa. World travelers came and many of them stayed. The globe-girdling expansionism was by design.

Something else happened, by chance, to stimulate Victoria's trade north and south: the Klondike gold rush. Until this time, goods had come to Victoria from San Francisco, either transshipped by rail or via the original, dangerous Cape Horn route. Now, around the turn of the century, the world suddenly opened. Merchants dealing at home and abroad began to live up to the new age of affluence, building big homes, giving big parties, and, of course, planting gardens. The servants, instead of being native Indians - who had never understood what the white man was up to anyway - were mostly imported Chinese, cast off after they had finished building the first railways and roads.

|

Victoria's Architecture

Architecturally, Victoria often borrowed the best from its British and American backgrounds. A young English architect, Francis Rattenbury, won a competition to design the present Legislative Buildings. Rattenbury ended his days ruinously as the victim in a sordid murder and sensational trial in England, but some of his finest monuments stand all around Victoria's Inner Harbour - classic, elegant public and commercial buildings of which he was either the sole designer or co-designer including the Empress Hotel and the original Crystal Garden. Samuel Maclure designed houses ranging from mansions to verandahed bungalows.

Along the scenic shores of Oak Bay, the famous Olmsted firm of landscape architects of Brookline, Massachusetts, laid out a 465-acre residential suburb called The Uplands. Based on a garden city concept then popular in England and the United States, it was so well conceived and has been so resolutely maintained as to have approached, in the words of one university professor, a state of immortality. Riffington was built as the showplace of The Uplands and its garden will be open for the ARS convention tours.

Early Public Gardens

During the first solid foundation-laying in homes and gardens, most of the landscapers and gardeners were Scots and Englishmen trained on home turf. In the public domain, attention was probably paid first to the grounds of Government House, the official residence of the sovereign's representative in British Columbia. (The present Government House is fairly new; its predecessor burned to the ground one night in 1957. The garden is usually open to visitors in daytime hours.)

|

|

'Malahat', a creation of the late Hjalmer Larson of Oregon,

who crossed the British hybrid 'Gill's Trimuph' with the hardy species R. strigillosum and named the offspring for the Malahat region, north of Victoria, which he frequently visited. He gave a cutting to the Weesjes, whose plant is illustrated here and was the first in British Columbia. They in turn gave a plant to Dave Dougan, who grows it on the Malahat. Photo by Fred Hook |

Civic pride was expressed in the creation of Beacon Hill Park where, roughly, Chief Factor and later Governor James Douglas had walked knee deep through fields of clover and tall grasses while searching for a site for Fort Victoria in 1842. The designer was John Blair, a Scotsman enticed out of retirement on Vancouver Island who had earlier laid out parks in Chicago. Among the tree plantings in 1889 were rhododendrons hybridized by the two Waterer firms of Surrey, England which Blair ordered from the nursery firm of Thomas Meeham and Sons of Germantown, Pennsylvania, including 'Mrs. John Clutton', a white; the still popular 'Fastuosum Flore Pleno', and 'Mrs. John Waterer'. The planting is still in situ at Fountain Lake. Supervising the planting that year at Beacon Hill Park was a much younger compatriot, George Fraser, who was to carry on with rhododendrons on his own and become Canada's first hybridizer of the genus.

Early Private Gardens

Meanwhile, private gardening developed according to the size of holding and the owner's leisure time and pocketbook, whether at rustic cottages with hollyhocks and lavender outside the front door or at the new stately homes. These people gardened for the sheer love of gardening, for personal satisfaction, like artists painting a landscape, often riotously.

Today we wonder how they did it without the horticultural information we have, without easy access to newly-improved hybrids, without refined fertilizers, without plastic. Financial gain from gardening was furthest from their thoughts.

|

|

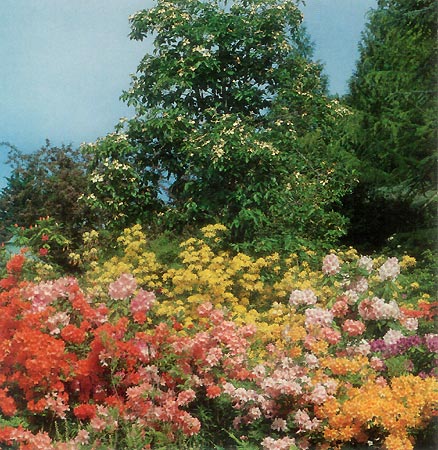

Rhododendrons & Azaleas

Photo courtesy of The Butchart Gardens |

When Jenny and Robert Pirn Butchart began building differently-styled formal gardens on their property outside Victoria, and day trippers came strolling by and asking questions, they would be distracted though welcoming. Butchart, pottering around in work clothes, could be and sometimes was mistaken for one of his hired gardeners.

Actually, they were fulfilling Jenny Butchart's passion for gardening and their own ideas of gracious living which included entertaining distinguished plantsmen from around the world, among them plant hunters like Frank Kingdon Ward. When they started out, to be sure, neither foresaw that the outcome would be the famously beautiful Butchart Gardens which last year drew nearly three-quarters of a million visitors.

The Butcharts were not rhododendron-azalea gardeners per se; their botanical interests were too far-ranging in terms of their day or, more precisely, rhododendron culture, being in comparative infancy when they started out, would have hedged their scope.

The men and women who emerge as the pioneers in rhododendron culture on Vancouver Island worked in out-of-the-way places quietly and slowly - very slowly it seems to us nowadays when we expect instant success in every human endeavor. They tended to start off in another branch of botany such as alpines and in the case of husband-and-wife teams, the wife was often the equal or better at plant husbandry. In the absence of statistical data, they first had to learn about the climate and soil of the largest island on North America's west coast.

|

|

'Transit Gold', photo by Stuart Holland, is Mr. Holland's cross between a cream form 'Royal Flush' that he

bought from the Griegs in 1958 pollinated by R. xanthocodon (L & S 17521) bought from the Greigs in 1960. The cross was made in the spring of 1963 and the seed sown indoors later that year. "Germination was good," he says, "and I grew on about twenty plants from which I selected one for naming and one other as a very good plant. I designated the plant Transit Gold' in May 1984 somewhat reluctantly because I have never been entirely certain that it is not similar to other cinnabarinum hybrids." The name, harking to his Transit Avenue home, is not registered. Photo by Stuart Holland |

Climatic and Geological Conditions

They learned what their fur-trade predecessors realized from their years of exploration: that not all of Canada was "a land of ice and snow"; that on the Pacific coast the summers were usually sunny and warm and the winters rainy, misty, and mild. (Captain James Cook, the first European to sail by on his third and final voyage of discovery in 1778, had complained in his journal about persistent fog along the outer coast.) While the latitude was the same as the southern tip of England, the main difference in climate was only later attributed to the warm Kuroshio current.

The earth itself was not uniform in composition. Scientists found that when the last Ice Age finished scouring the island 10,000 to 20,000 years ago, soil types of great variation had been left behind, among them heavy, poorly-drained glacial clays of the kind that most rhododendrons like least of all. The transported glacial clays, silts and glacier fluvial sediments have not had time to be weathered (oxidized and hydrated) and broken down into their mineral constituents. Rhododendron specialists had to find out for themselves that all planting sites were not born equal, which may explain why even today some relocate more than once in their search for the ideal habitat.

Rhododendron Pioneers

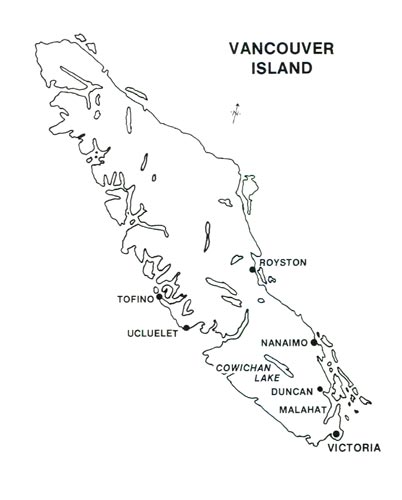

The first men and women to concentrate on the genus significantly did so not around Victoria but in wilderness to the north on Vancouver Island - George Fraser at Ucluelet on the west coast, George and Jeanne Buchanan Simpson in the interior at Cowichan Lake, and Ted and Mary Greig at Royston on the east coast. To put them into historical as well as geographical perspective, we need to form a triangle with Victoria and there add the name of Richard Layritz. By introducing species and hybrids and making them commercially available, these people led British Columbia and Canada into the world of rhododendrons.

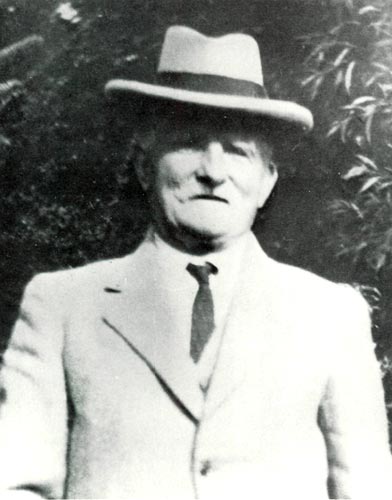

George Fraser

Fraser (1854-1944), trained as a gardener in Scotland, operated a nursery in Winnipeg of all unlikely places before moving west. In 1892 he took up a 236-acre preemption at Ucluelet, then and for a long time accessible only by sea, moved there in 1894 and in supreme isolation set about studying and growing

Ericaceae

, a true Scotsman at home among his heaths and heathers.

|

|

George Fraser, 1927

Photo supplied by Bill Dale |

In the family's rhododendron section, he wanted to produce plants from seed that would be true in color. He got seed and pollen by mail from England and the eastern United States, and he raised seedlings from those Beacon Hill Park hybrids.

Before long, he was shipping plants. Butchart Gardens has a planting of Fraser rhododendrons. By 1915, his catalog offered 'Boule de Neige', 'Mrs. John Clutton', 'Michael Waterer', 'Mrs. Milner', 'John Waterer', 'Mrs. Holford', 'Crown Prince', 'Doncaster', 'Stella' and 'Mrs. Waterer'.

Quite early, under primitive methods of his own devising, he also produced crosses from tree-rhododendron species. How quickly he gained an understanding of the likes and dislikes of the immigrant potential parents of promise and coaxed them into flowering amazes growers like Stuart Holland who, at his Oak Bay garden, saw his

R. discolor

bloom for the first time last year and has yet to have his

R. barbatum

(L. & S. 17526) blossom, both after thirty-one years of waiting.

The Buchanan Simpsons

The Buchanan Simpsons, like Fraser, seem to have been strongly drawn to lonely places. When they first arrived in 1914, Cowichan Lake could be reached from Duncan, twenty miles away, only on foot or by horse.

Among their few neighbors were an extraordinary couple, Richard Stoker and his wife, Susan, who had settled in the Cowichan district in 1900. Stoker had been a medical doctor with the British Army in India before his retirement and his wife was an artist-naturalist. While posted at hill stations in India, the Stokers had made expeditions into the mountains and become ardent botanists.

|

|

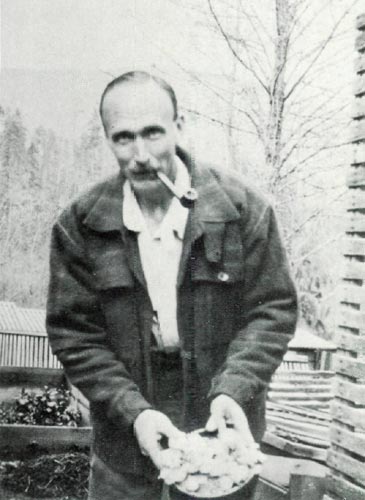

George Buchanan Simpson, 1932

Photo courtesy of Susan Mouat |

Though both in their fifties when they began clearing heavily-timbered land and building their log house at Cowichan Lake, they climbed mountains to collect native plants for their garden and then sent seed and plants far and wide. In return, they probably obtained rhododendron seed from the plant hunters' expeditions and from friends and professional collectors in India.

As the Stokers aged, they found worthy successors to their gardening enterprise in their younger plant-loving friends, the Buchanan Simpsons. During the 1920s and early 1930s, while helping the Stokers develop their garden and nursery business, the Buchanan Simpsons turned their attention more and more to species rhododendrons. They raised species from seed obtained directly or indirectly from the plant hunters. Their knack for selecting only those forms they deemed of value to hybridizers for decorative gardening was soon recognized in rhododendron circles.

In 1935, their pursuit took an unexpected turn. The diminutive Jeanne Suzanne Simpson, Sorbonne-educated and highly competent at plantsmanship, came from an old and aristocratic French family and that year, on the death of her mother, they sold their Marble Bay Alpine Plant Nursery business and its stock for $1,500, and went off to France with the intention of remaining there.

But by 1938, seeing the rise of Nazi Germany and the threat of war in Europe, they changed their minds, bought the adjacent Stoker property which an intermediate owner was willing to sell, and returned. With more space than they had before, they were able to develop the entire rhododendron plantings for their own enjoyment.

Dorothy Shaw of Duncan who, with her husband, knew the Buchanan Simpsons in this later period, describes them as purists whose stock, all raised in frames, could be relied upon for undoubted quality. Their seed exchange coterie and the Shaws' included the well-known Mrs. Rae Berry of Portland and the alpine plant specialist Ed Lohbrunner of Victoria.

The Greigs

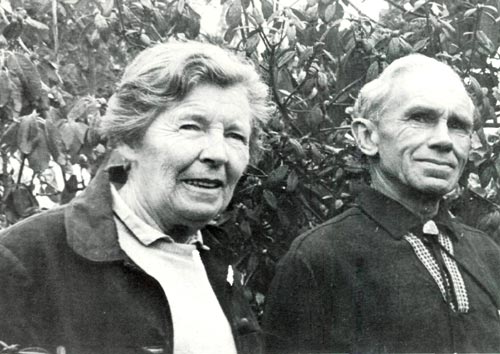

Ted and Mary Greig arrived as children in Duncan in 1910, during the great wave of British immigration. Ted Greig served overseas in the First World War and when he returned, they married and settled in Royston in 1919. Both were outdoors people, drawn to the hills.

|

|

Mary and Ted Greig, in the mid-1960's

Photo courtesy of Susan Mouat |

The Greigs became fascinated by alpines and this led to their purchase of the Buchanan Simpsons' nursery stock in 1935. The alpines did not fare well in their new and damper coastal environment, but the few rhododendrons they had taken reluctantly with the alpines did, so the Greigs focused their attention on them.

By this time they had four young children, and though hampered by a lack of literature, a chronic shortage of money, and little contact with other growers, they accumulated stock, from Britain, and by growing seed obtained from the plant hunters Joseph Rock, the partners Ludlow and Sherriff, and Kingdon Ward. Their exceptional talent for growing the wild collected seed and propagating only the best forms earned them the ARS Gold Medal in 1965.

Richard Layritz

Throughout the working span of all these individuals, giving continuity as rhododendron culture took hold on Vancouver Island and introducing species and hybrids, was nurseryman Richard Layritz (1867-1954). Born in Dresden, Germany and trained in horticulture at Stuttgart, he arrived in Victoria to start his first nursery in 1889, just when the building boom was under way. Many of the

Sequoia gigantia

ennobling the Victoria landscape today date to seed planted by him at this time.

In 1898 when he needed money to expand, the young man looked north and joined the rush to the Klondike. Unlike most of the gold seekers, he returned with the desired poke. Soon he had the first large nursery in British Columbia.

Described as the most colorful and competent nurseryman ever to operate on Vancouver Island, Layritz is said to have refused to sell plants to anyone he thought would not look after them. At one time, all the fruit trees of the Okanagan and other orchard valleys of the province's interior came from his nursery, as many as 40,000 in a single order. He grew roses by the thousands, shipping to Portland, called the City of Roses, and to fanciers as distant as Hong Kong. He supplied plants for The Uplands, Butchart Gardens and Victoria's tree-lined boulevards.

The firm's records show the stocking of more than 300 kinds of rhododendrons, "some from the high Himalayas", and, interestingly, in 1923, a new partner, Harry Scale, travelling for Layritz Nurseries Ltd., bought many new unspecified hybrid rhododendrons from the Rothschild nursery estate at Exbury, Hampshire, England. Since then, the Exbury Estate has become by far the largest and finest collection of rhododendrons in the world.

The Pioneer's Legacy

The work of Fraser, the Simpsons, and the Greigs will be recognized in papers and visual presentations at the ARS convention. 'Fraseri' was the first hybrid rhododendron (azalea) developed in Canada to receive international recognition. A lone plant of

R. canadense

strayed into a batch of cranberry plants shipped to Fraser from Nova Scotia. He crossed this east coast azalea, which was then called

rhodora

, with

R. japonicum

, a native of Japan, and the selected offspring was named in 1920 by William Watson, curator of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, who described the color as "a bright rosy-mauve." The great plant hunter Ernest Henry Wilson of the Arnold Arboretum in Boston considered 'Fraseri' a promising and hardy hybrid with "a pleasing shade of light rose-lilac." However, George Fraser's hybrid inspired by the roving parent went into obscurity in the progress of the much showier Knap Hill and Exbury azaleas.

The phlox-pink 'Buchanan Simpson', on the other hand, is widely propagated today. Originated by the Buchanan Simpsons and named for them and registered by the Greigs in 1963, this hybrid is listed in Greer Gardens 1988 catalog with the notation: "Among the group of newer hybrids not yet well known, this thick, bushy rhododendron shows real promise."

Mary Greig, in correspondence with Stuart Holland, has stated that 'Buchanan Simpson' came with the nursery purchase in 1935 and that she believed it was an

R. erubescens

hybrid not necessarily made by the Buchanan Simpsons but from wild collected seed pollinated in nature. The other partner is unknown.

While their Royston nursery was noted for species propagation, the Greigs made numerous crosses of which only a few were named - 'Butterball', 'Edith Berkeley', 'Cyril Berkeley', 'Mary Greig', 'Ted Greig', 'Veronica Milner' and 'George Watling'. Their nursery also distributed 'Royston Red', a

R. repens

x

R. thomsonii

F2 cross whose original plant came from Sunningdale Nursery in England. 'Royston Red' was named by Alleyne Cook of Vancouver, who also gave names such as 'Royston Festival', 'Royston Spring', and 'Royston Opaline' to some

R. auriculatum

hybrids made by Mary Greig which have bloomed in Vancouver's Stanley Park planting.

The Greigs made the most lasting contribution on the basis of volume and quality of production, with their donations of close to 1,000 plants in 1952 and 1954 which laid the foundation for the collection of rhododendrons at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and their sale in 1965 of the balance of their rhododendron stock to the Vancouver Parks Board. Shortly before the Greigs' donations to UBC, the campus grounds had been designated as a botanic garden and there were very few rhododendrons. Only later were separate areas established to include an Asian garden with a collection of rhododendron species.

Of the five pioneers, Mary Greig is the only one alive today. Now in her 92nd year, she still lives in the house she entered on her honeymoon seventy years ago, and still enjoys her garden. She knows the problems that all her colleagues had in forming their collections. All the time, they worked against the information gap, unreliable transportation, and quirks of weather.

The massive collections formed by the pioneers had varying fates. Fraser was a life-long bachelor, and, when he died, wilderness reclaimed his garden. Some of his rhododendrons were transplanted by district gardeners, and survive today, along with their progeny.

The Buchanan Simpson property was given to the University of Victoria in 1966 by Jeanne Suzanne Simpson, after her husband's death. The university removed more than 250 plants, including 160 species rhododendrons many of which did not survive the handling and sitting. (In the last year, the University has been moving 200 rhododendrons, the survivors among them, some up to eighteen feet high, to a better-drained location.)

When the rest of the Greig nursery stock was sold to the Vancouver Parks Board in 1965, the timing of removal proved less than fortunate. Civic workers went on strike and many small plants died for lack of watering. Larger plants made it through the summer and are now in Vancouver's Queen Elizabeth Park and Stanley Park.

In their day, all three propagation sources were supplying other nurseries. Fraser, for example, shipped plants to Layritz by coastal steamer. And all of them helped immeasurably in the building of other private rhododendron gardens on Vancouver Island, notably those of Edith and Cyril Berkeley at Departure Bay, Nanaimo, and C.T. Hilton at Alberni. Most of the Berkeley plants were obtained from the Greigs, a few from Fraser and the Buchanan Simpsons. Fraser is thought to have been the source for the Hilton rhododendrons, a large bed of which is now in Queen Elizabeth Park in Vancouver.

Private gardens in Victoria also benefited. Albert de Mezey obtained stock from the Greigs, Layritz, and the Reuthe nursery in Kent, England for his garden at Kildonan, a Maclure mansion which he restored after its wartime use as military quarters. "My own best hybrids used the Greig form of

R. campylocarpum

, yellow with a red eye."

Stuart Holland, recalling two outstanding rhododendron gardens of forty years ago at Victoria, says: "One belonged to Joe Worth; he had a fantastic rhododendron garden. He actually had a steam sterilizer for treating his soil. His was the only garden I've known where the blue poppy

Meconopsis betonicifolio

f.

baileyi

self-seeded all over the place. The other garden belonged to Dick and Beryl Edgell. Most of their plants came from the Greigs, and I suspect Worth's did, too."

The Holland garden is long and narrow and rampant in rhododendrons, and, as he spoke, it was hard to keep an ear on what he was saying because my eyes were being drawn steadily upward, higher and higher, up to the open crown of his

R. arboreum

where blossoms hung like lucent rubies, glowing against a blue sky. The

arboreum

grew from seed sown in 1960.

Today's Gardens

The Milner Garden

The Greig nursery was the source of most of the rhododendrons at Long Distance, the Qualicum home of Mrs. H.R. Milner, for whom 'Veronica Milner' was named. The garden was developed between 1952 and 1956, and now, in maturity, is outstanding for its native and exotic trees.

The landscaping is in the tradition of the English country house; indeed, Mrs. Milner's interest in gardening goes back to her childhood in England, to her memories of the home of her grandmother, Lady Wimborne of Canford Magna, Dorset, with its seven-mile-long drive. Among the Milner rhododendrons are big-leaf species including

R. rex

, some hybrids seldom seen today and her own favorites, 'Mrs. Walter Burns', 'Beauty of Littleworth' and 'Venus'. "We collected our rhododendrons from around the province - from Mary Greig, from Eddie, and from Hyland Barnes in Vancouver," she says.

The Abkhazi Garden

Like the Milner garden, most of the major private rhododendron gardens on Vancouver Island today have been made since the Second World War, either as entirely new gardens or remakes on sites of intrinsic merit. Seaside or lakeshore property with an attractive house and ample water for gardening would have been chosen by many people, but one couple set their hearts on an urban acre of rock and oak trees.

For Prince Nicholas Abkhazi and his wife, the former Peggy Pemberton-Carter, this site had all the intrinsic merit they wanted. Putting first things first, they landscaped before building their house. Consequently, as these gardener-artists fulfilled their dream, no part of the composite picture looks like an after-thought. Everything is so integrated as to appear more as a philosophical state than a brilliantly-designed garden. (See

ARS Journal

Vol. 42:4, Fall 1988.)

|

|

Abkhazi Garden

Photo by Bill Dale |

Herman Vaartnou's Garden

The English garden writer Vita Sackville-West once remarked that few of our gardening ambitions turn out as planned and when they do, we are surprised. Not so Herman Vaartnou, expert grower of big-leaf species rhododendrons. He, too, was a careful planner of his less-than-an-acre Uplands property which he bought in 1976 and planted the following year with stored plants collected since 1964.

Vaartnou has a doctorate in botany from Corvallis, Oregon, and was formerly in charge of landscaping at UBC. He is a selector, not a hybridizer: "As a selector, I get ten years ahead; hybridizing takes too long at my age." His garden now has 250 species including difficult-to-grow members of the Grande, Falconeri, and Maddenii series, as well as 150 hybrids. If he were again to start designing his garden, he says he would do exactly what he has done.

Woodcote

The rhododendron garden at Woodcote, the home of Peter and Pat Stone at Quamichan Lake near Duncan, is an example of a garden rebuilt over the last thirty years. The specimen trees were there and eight rhododendrons at the most. The Stones dispensed with a tennis court, and redesigned the grounds to create lawns, rockeries, and beds for rhododendrons. Year by year, they have added rhododendrons - old and new hybrids and species.

Looking around at rhododendron gardens on Vancouver Island, most old hands at the game agree that they have never been better than today. The wealth of material and the bounties of increased expertise have made the difference, especially for gardeners who know their ground and who have spent years observing and learning the peculiarities of their microclimates.

Dave Dougan's Garden

Dave Dougan, president of the Victoria Rhododendron Society, typifies this new generation. A logging operator and descendant of Cowichan Valley pioneers, he grew up in the woods. He has been studying and growing rhododendrons long enough to remember spotting the first Exbury-form

R. yakushimanum

to appear on Vancouver Island in the 1950s, a few years after Lionel de Rothschild's two plants from Japan had won instant acclaim in England. The Victoria nursery was asking $20 for the little Yak and Dave Dougan has regretted ever since that he did not buy it. Albert de Mezey picked it up instead, used it for hybridizing, and still has it in his garden.

Dougan built a succession of rhododendron gardens on southern Vancouver Island before settling on a steep slope on the Malahat, fifteen miles north of Victoria. As one of the subdivision's developers, he took his pick of view sites 500 feet above sea level for his wood-and-glass house, made a pond, fed by a 400-foot-deep well, and began rockscaping more than landscaping, planting in pockets, while taking full advantage of big arbutus trees which characterize the Malahat. As a woods operator, he knows where to get sedge peat for his rhododendrons. After six years, the results astonish visitors.

|

|

David Dougan Garden

Photo by Fred Hook |

Ken Gibson's Garden

At Tofino on the Island's west coast, not far from George Fraser's haunts, Ken Gibson has transformed a cone-shaped miniature mountain into a rhododendron garden of exceptional beauty which he described and illustrated in this Journal's Winter 1987 issue. A contractor and former logger who knows his region forwards and backwards, Gibson goes to no end of work in caring for his plants. He gets mulch by raking up twigs, fir needles, and bark from the shores of Kennedy Lake, and then trucks the debris miles home. He was first encouraged to grow rhododendrons by Betty Farmer who, with her sister Jo, were the district's leading rhododendron gardeners during and after Fraser's time.

The Weesjes' Garden

Amid huge Douglas firs on property close to Victoria, Evelyn and Nick Weesjes have spent seven years designing and laying out the largest rhododendron collection on Vancouver Island, certainly of species. The forested setting resembles that of the Species Garden at UBC's Botanical Garden where Nick was head gardener and Evelyn the staff propagator. Each had a hand in caring for the gift rhododendrons from the Greigs. When UBC cooperated with the Rhododendron Species Foundation in propagating plant material obtained from major gardens in the British Isles, they were both involved. Evelyn was awarded the ARS Gold Medal in 1971 for her work for the Foundation in species propagation.

In their hand-preparation of the present seven-acre garden, the Weesjes retained many native plants - firs, balsams, broad-leafed maples, alders, cascara, arbutus, yew, huckleberry, Oregon grape, sword ferns. Besides planting several thousand rhododendrons, stock raised privately during their careers, plus hundreds of other trees and shrubs, they installed a watering system that ensures each plant its own sprinkler nozzle or dripper. To any onlooker, the Weesjes' professionalism shows in the condition of their plants.

|

|

Weesjes Garden

Photo by Evelyn Weesje |

Whether done by hand or the aid of heavy machinery, these gardens exemplify the new spirit of do-it-yourself-without-a-small-army and do it fast, while you are still able. The Weesjes' garden was opened to a public tour for the first time last year. Having to live in a time warp, especially where certain species are concerned, rhododendron people can best appreciate the scale and speed of these accomplishments. Beyond this, however, is the stimulative effect on public interest.

Public Awareness of Rhododendrons

Indeed, interest in rhododendrons has grown so much in the last few years that most observers are at a loss for a simple explanation. They feel that it is due partly to modern color printing and a burst of gardening books, each more specific than the previous one, as well as new Canadian magazines like

Harrowsmith

and television programs, notably The Canadian Gardener, produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, both of which instantly found a surprisingly large following in the U.S.

Enthusiasm has also risen with the development of smaller hybrids of intriguing colors that blossom profusely early in life, calibrated to the faster pace of life and the rise of an affluent middle class with the disposable income to buy them. A friend who lives in Ontario writes: "What is happening? Even my mother's chartered accountant (in Vancouver) is growing rhododendrons."

Actually many of the new aficionados are eastern Canadians retiring to the west coast to escape harsh winters and indulge in year-round gardening. Although with the development of hardier hybrids, rhododendron-growing is reaching into the province's interior in a way that would not have been thought possible thirty years ago.

In the upsurge, British Columbians who prize rhododendrons above all their garden plants are no longer regarded as eccentric. Their reference sources are less likely to be publications of the Royal Horticultural Society than this Journal or catalogs of leading hybridizers and growers who belong to the ARS.

Recognition of Pacific Northwest Hybrids

In the reversal of the flow of information and brood stock, the brilliant latter day hybridizers of the Pacific Northwest have become household names among progressive growers in England. If British Columbia is regarded as part of the Pacific Northwest, we can include among these hybridizers Vancouver's Jack Lofthouse, creator of 'Sierra del Oro' and 'Sierra Sunrise'.

Late last spring, when we visited the open silver birch canopied garden of the prominent rhododendron specialist and wholesale nurseryman in Devon, after we had admired his "Indumentum Walk", a pathway lined with rhododendrons whose under-leaves showed colors ranging from dark purple through the browns to silver, he turned to us and asked: "Did you know Halfdan Lem?''We replied that we had not been "into" rhododendrons when Lem was active, but wished we had met him since we hold him in much the same light that other Canadians do a hockey star. We then looked at fledgling plants in Dick Reynolds' nursery rows and saw on the labels 'Lem's 121', 'Isabel Pierce' and other hybrids of Lem's imaginative devising among those of West Coast hybridizers.

ARS Chapter Growth

The enthusiasm for rhododendrons is reflected in the growth of ARS chapters. In the last year, new chapters have sprung up on Vancouver Island and the mainland. The membership roll of the Victoria chapter doubled from 1985 to 1987. Many of the present 130 members tend to view this as a direct spinoff from Bill Dale's leadership. Dale, a retired pulp mill executive, is a first-rate organizer. Through his efforts, members have come to expect that every monthly meeting features an outstanding speaker and that every garden tour moves along without a hitch. When he is not recruiting members or introducing novice members to pros, or writing or researching rhododendron lore, or tending his own rhododendrons, he is likely to be off on one of the Gulf Islands speaking to a garden club - about rhododendrons. Essentially, he is a communicator.

In this respect, the other attraction for members is an exceptional newsletter prepared and edited by Alec McCarter, a retired academic. McCarter's knowledge of botany and his flair for selecting unusual material from hither and yon result in issues deserving of much wider readership.

The Future?

What of the future of rhododendron gardening on Vancouver Island? It looks fine right now for urban gardeners for whom the new and coming small and floriferous hybrids seem tailor-made.

For the country gardener laying out large plantings of young, small-leaf rhododendrons there are problems, the most serious and immediate being how to protect plants from nibbling deer without going to the expense of high fencing. In the past, one shot the deer. The Buchanan Simpsons had venison for dinner for the simple reason that other meats were not available to them. Today most British Columbians cherish the province's wildlife and consider deer-killing definitely uncivilized.

A greater concern, one that scientists have raised only recently, is the prospect of a drying trend in the northern hemisphere which could make the severe winter frosts of 1955 and 1985 almost "normal". As we write this, a television newscast tells us that four abnormally dry summers are taking a toll of young Western cedar and Grand fir trees on Vancouver Island. Stressed, these youngsters are dying in alarming numbers either from lack of ground moisture or disease vulnerability. The scientists point to three possible causes: the "greenhouse" effect, air pollution (acid rain in particular) and depletion of the Earth's ozone layer.

In our microclimate, on property we have hacked out of the wilderness, we have watched young trees of both native species die during or after each of these last few summers. In personal terms, much as we love our exotic rhododendrons, we also hate to lose our natives to forces beyond our control. The predictions of a drying trend could have serious implications for rhododendron culture. While listening, we can only try to maintain a spirit of optimism, remembering that the intrepid plant hunters who started us off on the rhododendron trail often went through hell and back too.

Acknowledgments:

Bill Dale, biographical information on George Fraser.

Dr. Stuart Holland, assistance with the history of nurseries and gardening on Vancouver Island.

Susan Mouat, biographical information on her parents, the Greigs.

Dorothy Shaw, biographical information on the Buchanan Simpsons.

Bibliography:

C.N. Forward, editor,

Vancouver Island - Land of Contrasts

, University of Victoria, 1979.

Ted and Mary Greig, "Rhododendrons on Vancouver Island",

Proceedings of the International Rhododendron Conference

, Portland, Oregon, 1961.

Lillian Hodgson, "George Fraser",

ARS Quart. Bulletin

(Vol. 30:4)

Roy Taylor, "Rhododendron Species - A Developing Collection At UBC"

Davidsonia

(Vol. 4:2).

When the American Rhododendron Society's annual convention is held in Victoria this spring, it will be only the second time in Canada. The first was held in Vancouver in 1979. The host is the Victoria Rhododendron Society, a chapter of the ARS. The group was formed in 1979.

Leslie and Frank Drew, members of the Victoria Chapter, are actively involved in planning and publicizing the 1989 ARS Convention.