Growing Rhododendrons in Warm Climates

Willis Harden

Commerce, Georgia

"The culture of Rhododendrons is moving southward as more is learned about their special requirements and interested gardeners are experimenting with varieties and culture."

Rhododendron Information

, ARS, 1967.

Although rhododendrons have specific and universal requirements it has taken many years for us to realize that the methods used to grow them well in Georgia are very different from the methods used in Oregon. In this article I will try to point out those differences and hope that these opinions, formed by my experience in the upper piedmont, will be useful to those further north as well as in the coastal plain, areas that have the same problems, varying only in degree.

Heat Tolerance - As commonly used, this term might be defined as the ability of rhododendrons to thrive in hot areas when grown by methods appropriate to cooler areas. According to this definition relatively few rhododendrons are heat tolerant. However, correctly the definition might read - The ability of a rhododendron to resist disease (fungus) when grown in a warm, humid environment, if appropriate growing methods are used. Using this definition the percentage of heat tolerant rhododendrons rises to nearly 100 per cent.

Cold

- This is the limiting factor in growing rhododendrons. The 1980s have been useful in that, in this area, every extreme of weather has been encountered and the effects noted. Incredibly, since 1980, we have had the lowest temperature, the lowest December temperature (not the same), the latest hard spring freeze, the hottest summer, the severest drought and the second severest drought ever recorded. Scientists claim from studying growth rings on ancient submerged cypress logs that 1988 was the driest in 1,300 years. Yet, throughout this eight year period of extremes, the only significant losses we incurred were due to the cold (20 degrees F. on April 20, 1983 and minus 8 degrees F. in January, 1985).

The heat of 1980 was unprecedented. The temperature was 100 degrees and over for weeks with daily lows of 85 degrees and over. I ran my irrigation pump around the clock for at least three weeks without a break and tried to time the twice daily routine of moving sprinklers as closely as possible to dawn and dark. During this period I realized that the heat, while unbearable to me, was having no adverse effect on the rhododendrons. We had spectacular growth that year and a record bud set.

I have concluded, based in part on these experiences, that up to a point the further south one goes the larger number of rhododendrons it is possible to grow. Beyond that point, at approximately the fall line in the southern states, factors such as lack of winter chilling and high night temperatures begin to limit what can be grown satisfactorily.

Altitude

- Various diseases of rhododendrons result from fungus which only grow in the combined presence of heat, moisture, and darkness. High altitudes brings nighttime cooling; thus disease prevention becomes more of a necessity at low altitudes. Daytime temperature, provided enough water and shade are given to prevent dehydration, is not important.

An interesting discovery for me was a beautiful, large

Rhododendron

'Crest' growing in the Paul Maslin garden in Denver, Colorado. 'Crest' has been unsuccessful for most who have tried it in the South, with root rot or tenderness usually being blamed. Yet Denver is considerably colder in winter and about as hot in mid-summer as Atlanta. This is a good example of the effect of low humidity and night cooling.

Site - The first step to successful rhododendron growing is to pick a location where dehydration will not occur in summer or winter and this means a site out of the wind and with dappled shade, preferably from evergreens. The usual advice to avoid a frost pocket does not apply in the South and a low lying site should be sought. Unlike the Northwest where the damaging freezes of 1955 and 1972 came early, and unlike Britain where damaging frost can come almost anytime, our risk is from Arctic air that comes in midwinter following little or no previous cold and catches plants in a soft condition. Planting in a frost prone site not only will help with the problem of inducing dormancy, but it will likely be out of the wind when real cold arrives.

Protection - If rhododendrons can be shielded from wind, almost no amount of cold will damage them. We keep a supply of old bean hampers around to place over young plants, and when they get too large for that we mound leaves and pine needles around the trunk as high as possible and cram handfuls of leaves into the branch structure or anywhere they can be made to stick. Using that treatment we prepared for a cold wave this past winter and although the temperature reached 10 degrees F., the coldest in three years, there was no obvious damage to such rhododendrons as R. edgeworthii , R. ellipticum , R. griersonianum and R. spinuliferum .

Growing Season - The effect of our long growing season is very beneficial to some rhododendrons and detrimental to others. In the case of many alpine types the result is multiple growth flushes and early blossom bud set which is often blasted. However, there are a number of rhododendrons that need a long growing season and these include the reds containing the blood of late blooming species such as R. griersonianum and R. facetum and hybrids such as 'Damozel', 'Grenadier', 'Jutland', 'Kilimanjaro' and 'Romany Chal'. This famous group of hybrids are regarded as somewhat tender in England, but provide some of the most hardy and reliable types in the South, obviously doing better with a long growing season.

Planting

- In warm climates rhododendrons must be grown in elevated spots, either raised beds for group plantings or a built up mound for each plant. The medium must be primarily organic with large particles, containing a good bit of air, moisture retentive, and the same time rapidly draining. Absolutely no clay should enter the mix and fine particle materials such as peat or old bark should be used sparingly if at all.

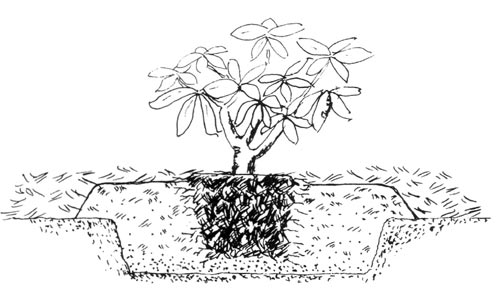

For planting a single rhododendron in the typical woodland site in our garden, which is a light brown soil with fair organic content in the top 8 or 10 inches, and hard clay about 15 inches down, we first rototill to a depth of 18 inches and a diameter of 3 feet to remove tree roots. We dump in a large wheel barrow of medium pine bark and mix it in with a pitchfork. Then we add another load of bark and mix it into the top layer, with the aim of making a smooth transition from almost all mineral soil in the bottom to pure organic at the top. The resulting mound is flattened across the top and the rhododendron planted with the crown an inch or so above the surface. The area is then mulched heavily with coarse bark but the mulch layer is tapered so that it forms a very thin layer over the roots and none rests against the trunk.

|

|

Planting diagram for rhododendrons in the south. Raised

bed has mixture of soil and bark below rootball, mixture around rootball is mostly bark, mulch on top is coarse bark. |

Mulch

- The use of pine straw, the most common mulch in the South, has one serious drawback. After repeated applications the bottom layers develop a dense sodden thatch excluding air. Control of this problem by either replacing the mulch occasionally or turning it (bringing the bottom layer to the top) is not entirely satisfactory as needed humus is thus not replenished in the soil. Both of these solutions are also time consuming. I should note that sellers of needles from long leaf pines which are collected on the coastal plain maintain that their mulch is superior to others and it may well be.

Coarse pine bark is the perfect material to mulch with in my opinion. It will not pack or crust and eventually breaks down into a soft crumbly substance. Proof of pine bark suitability as both a mulch and medium is the fact that I have thirty year old beds that were originally knee deep in pure bark and rhododendrons added to these beds as they exist today have thrived without the need for any additional material. All species of pine don't yield equally suitable bark. In this area short leaf and loblolly pines have good bark while white and Virginia pines have bark that is too thin and is removed in slivers or plates.

Composted hardwood leaves, especially oak and hickory, make good mulch in this area, but in a large planting bark is easier to come by. Probably other coarse organic materials are locally available and worth trying.

Spraying

- A few years ago Dr. Eugene Moody, a well known plant pathologist and rhododendron expert with the University of Georgia, advised me to begin a regular spray program. The results were so positive that a desire to report them is the main reason I decided to write this article. There is no question that the use of fungicides, particularly Benlate (benomyl), allows virtually all of the rhododendrons that are grown in the Pacific Northwest to be grown in the upper South and allows a good selection to be grown on the coastal plain as far as central Florida. I know that there is a desire by some gardeners not to use chemical aids, but for rhododendrons above ground, there is no alternative. Without spraying dieback is rampant and Benlate is totally effective in controlling it. On the other hand, root disease can be effectively controlled by proper planting although spraying with Subdue is a good insurance policy.

We use a frequent spray schedule in the nursery because of the watering required in container culture, but have found that spraying monthly works well in the garden. We use Benlate plus Manzate and a spreader sticker to control a wide variety of diseases. Every third spray we use Daconil which is more effective against leaf diseases. It is important not to spray in hot sunshine or when the foliage will not dry quickly or burn will result. There is no need to spray when night temperatures fall below 50 degrees F.

Following the disastrous series of freezes in the early 1980s a large number of rhododendrons went into decline. Dieback organisms were finding easy establishment in damaged and bark split wood. Dr. Moody recommended painting the wood with a double (2 tbs. per gal.) solution of Benlate. Declining and near death specimens have completely recovered with this treatment. A neighbor, Jeff Beasley, has had the same experience with Benlate. I remember telling Jeff he should cut some old rhododendrons down and he said his mother would never agree. About the same time Dr. Moody started them with Benlate spraying and after three years the rhododendrons have been rejuvenated and look better than ever.

Bare Rooting - In areas with cool soil temperatures, rhododendrons can be grown successfully in a planting medium with fine particles such as peat, sawdust and some clay. Rhododendron roots should be examined when received from any source and if they are in this type of medium they should be bare rooted and the medium replaced. This compacted medium is also typical where plants have been in the same container too long. Bare rooting is more safely done in the fall.

Age - Rhododendrons increase their resistance to root rot as they get older. Small plants should be kept in containers or raised beds of pure organic matter until they are at least three years old.

Yellows - They are usually avoided by Southern growers because of the susceptibility of some cultivars to dieback. However, with spraying the problem can be eliminated. Modern yellows are usually complex, containing blood from such "heat resistant" species as R. aberconwayi , R. discolor or R. griersonianum , in addition to difficult species like R. wardii or R. dichroanthum . If the grower doesn't want to be bothered with much upkeep there is a good choice of easy yellows available.

Varieties - Gardeners attempting rhododendrons in the lowland South should try species found in the following series, and their hybrids: Arboreum, Auriculatum, Barbatum, Fortunei, Griersonianum, Irroratum, Ponticum, Triflorum, Taliense. This list is just a suggested starting point.

Watering

- More often than not, watering is done incorrectly and seldom is enough water used. Some people have a misplaced idea that keeping rhododendrons on the dry side will prevent root rot, when actually root damage leads to Phytophthera infection and can be caused by dry conditions as well as excessively wet ones.

As rhododendrons, especially in the South, are woodland plants, the effect of watering on nearby trees must be taken into account. Shallow watering tends to encourage tree roots to grow near the surface and spot watering leads the tree roots into rhododendron beds where they are not wanted.

The aim of watering should be to duplicate natural rainfall, which means overhead watering of the entire area where rhododendrons are planted. This is facilitated by devoting certain areas of the garden to rhododendrons. In our garden we try to plant azaleas in areas where they can be watered only in extreme drought, and rhododendrons in other nearby areas where they can be watered regularly. Native azaleas are planted in areas where water is not available.

In addition to about 55 inches of normal rainfall, we add between 20 and 40 inches of irrigation water per year. We run sprinklers, usually the rainbird type, for twelve hours in each location and allow a week or longer between cycles. This type of watering is only possible with correctly planted rhododendrons.

Fertilizing - Southern gardeners should keep soil very acid as a root rot preventive. For my conditions I have found 3 parts Osmocote, 1 part ammonium sulfate, part Esmigram (minor elements supplement) and ⅛ part Epsom salts to be a satisfactory fertilization program. For some varieties, for example 'Paprika Spiced' and R. occidentale , additional small amounts of Epsom salts are needed after the regular spring application of fertilizer.

Maintenance - One important routine is to check plants in early spring to make sure that leaves that have fallen the previous year have not collected against the trunks and over the crowns of the plants. In areas of the South subject to root rot, which is everywhere except possibly the highest mountains, any buildup that has a tendency to cut off air should be hand raked off the plant. Insects are less of a problem in the South than in other areas. The only insect we spray for outside the nursery areas is lace wing, and then only when it is noticed. Borers appear to be more of a problem in the mountains. West coast grown plants should be watched very carefully for evidence of black vine weevil, and if found they should be thoroughly treated, either with Turcam as a drench or a summer schedule of Lorsban on the foliage. This is one pest that does not need an introduction here.

Conclusion - Successful rhododendron culture in the South is dependent on a combination of excellent drainage and plenty of water, with spraying for disease prevention. By following these suggestions, rhododendrons can be grown in gardens in areas of the South where they are unknown at the present time.

Willis Harden, Azalea Chapter member, is the proprietor of Homeplace Garden nursery.