A Day at Dawyck

Martha Prince

Locust Valley, New York

Twenty-eight miles south of Edinburgh, in a green and placid valley where the river Tweed wanders between blue hills, lies Dawyck Botanic Garden. This beautiful and historic garden, especially noted for its conifer collection, is now an outstation of the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. It was given to the nation in 1979 by Col. Alastair N. Balfour, who still lives in Dawyck House. Col. Balfour, by the way, is a member of the Scottish Rhododendron Society, a chapter of the ARS.

The story of the garden is the story of three Scottish families, all with an intense interest in arboriculture, who developed the garden over the centuries. The first was the Veitch family, the earliest recorded owners of Dawyck. European silver firs (

Abies alba

) still standing in Heron Wood are known to have been planted by them in 1680. The succeeding owners, the Naesmyths, bought the land in 1691, and for two hundred years they planted trees from all over the world. Sir James Naesmyth was a pupil of the great Swedish botanist Linnaeus, and it was Linnaeus himself who presumably planted a European larch (

Larix decidua

) in the garden in 1725. This venerable tree is there today. A later Naesmyth, Sir John, subscribed to plant expeditions to the Far East and to our American Northwest. Among the great surviving conifers are Douglas firs (

Pseudotsuga menziesii

) dating back to 1834, and grown from seed collected by David Douglas. One of these, in Scrape Glen, now towers at more than one hundred and fifty feet. Naesmyth's interest in trees extended beyond conifers. One day when walking among a planting of young beech seedlings he noticed an unusual upright form and had it placed near the house. This is the famous

Fagus sylvatica

'Dawyck', the fastigiate Dawyck Beech, now seventy-five feet tall and the noble ancestor of trees in other gardens.

The present architectural form of the garden - the terraces, paths, steps, bridges and ornamental stonework - also dates to Naesmyth days. A team of Italian landscape gardeners laid out these most attractive features during the 1820s. Stately stone Dawyck House was built in 1830, replacing an older home. Although the house is private and not part of the botanic garden, carefully designed and framed views of it are an integral aspect of the garden in several places.

|

|

Dawyck House

Photo by Martha Prince |

In 1897, Mrs. Alexander Balfour bought the estate from the sixth Naesmyth baronet. Her son Frederick R.S. Balfour (twenty-four at the time of the purchase) continued the great tradition of Dawyck. He spent several years in California and explored our Pacific Northwest - with plants much in mind. Among the trees he sent home to Scotland was the splendid and rare Brewer's spruce ( Picea brewerana ), from the Siskiyou Mountains of Oregon. Also, Balfour added rhododendrons to conifers and other trees as plants wanted for the garden. (The Naesmyths had grown only Rhododendron ponticum , R. catawbiense , R. maximum and a few hybrids.) He himself sent home from America our beautiful pink R. vaseyi ; the only notation I found about it was "from east of the Rockies." East indeed it is - nearly 1,500 miles east - but what a strange way to identify the mountains of North Carolina! I would suspect he did not find them in the wild himself. Balfour once visited Dr. Charles Sprague Sargent at the Arnold Arboretum and as a result received a collection of the Wilson rhododendrons from the 1906-1909 expedition to China (sponsored by the Arboretum). He later obtained Forrest seed as well.

|

|

Narcissus

and conifers

Photo by Martha Prince |

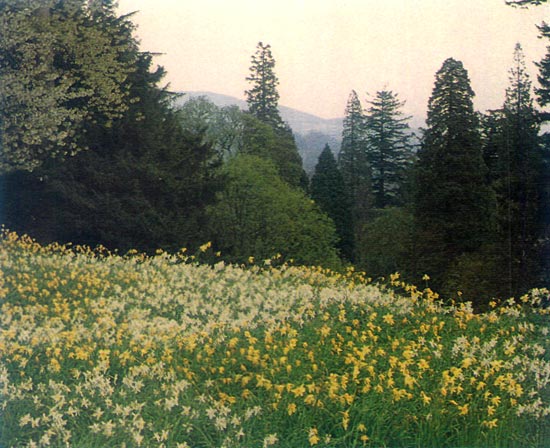

In addition to the trees and rhododendrons that Balfour planted at Dawyck, there are the daffodils. Drifts and sheets and battalions of

Narcissus

, in varying yellows and white, are everywhere. Seen against a background of conifers, they create a quite magical effect. In each of twenty successive years he is supposed to have planed one ton of bulbs! Indeed, Balfour made but one possible mistake in his imports; he was interested in fauna as well as flora. In the early part of the century he had a small herd of Sika deer sent from Japan. Some escaped from the ten-foot stockade he erected and began dining in the garden. These deer showed gourmet taste; they especially delighted in lunching on

R. cinnabarinum

.

F.R.S. Balfour died in 1945. His son, Col. Alastair Balfour, succeeded him to both the pleasures and responsibilities of caring for a great garden. During the next thirty-four years Col. Balfour contributed especially to the continued growth of the rhododendron collection. His gift of Dawyck to the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, insures the garden's future. After I have taken you with me on a spring time walk through this extraordinary place, I will mention some of RBGE's plans for both maintenance and growth.

There were several reasons my husband, Jordan, and I wanted to see Dawyck. Prominent among them was the climate; this part of Tweeddale is one of the coldest areas in Scotland, and the rainfall is not high. This compares in important aspects to our climate on Long Island. While we have visited the lush gardens in the warm and rainy west of Scotland, we could only be futilely envious of the Grandias, Maddenias and other tender plants there. At Dawyck, the all-time low temperature is -4° F, and the usual year may see zero. This is much like our winters. True, the summer highs are not as bad as ours, being only in the low 80s - a temperature of 75° F is considered "warm." There can be very late spring frosts, which nip the flowers on early species, and winter winds sometimes do serious harm. Rainfall averages 38 inches, just a bit less than on Long Island. I think that any species which does consistently well at Dawyck should at least be tried in our area. The biggest problem would probably be heat tolerance, not cold.

Before our visit, I had some very helpful correspondence with G. Broadley, Assistant Curator, Arboretum Department/Dawyck, at RBGE. Although he could not be there himself he thoughtfully arranged for us to be shown about by the resident garden supervisor, D.L. Binns.

Our visit was on May 8, a disappointingly gray and hazy day. We were staying at a delightful country inn just north of the small riverside town of Peebles and started out for the garden after a hearty Scottish breakfast. The road to Dawyck (B 712) is a lovely, narrow one, lined with clipped beech hedges, fields of new-plowed earth and green meadows dotted with grazing sheep. Here and there are stone walls, clusters of pine trees and mounds of bright yellow gorse bushes. At the turn to Dawyck was a meadow of black sheep; we had never seen black sheep before.

We found David Binns, a tall and bearded man with a friendly smile, expecting us in Dawyck's small office building, and off we went for a quick guided tour. Although Dawyck House and the lawns surrounding it are on level land, the gardens slope gently uphill toward the south and east. The rise is cut only by the passage of a pretty stream, Scrape Burn, ambling toward the Tweed. As we headed up the path, David warned us that there had been three days of severe frost (22 ° F) just two weeks before, and many early flowers were hit. That soon became obvious. The first damaged blossoms we noticed were on

R. strigillosum

, limp and brown instead of crimson. Further on,

R. lacteum

had its pale yellow flowers destroyed. David called early-blooming rhododendrons "dangerous."

Another problem here is that the mature rhododendrons, while known to have originated with Wilson, Forrest and others, are without collection numbers. Existing records are poor. For instance, we stopped at a large and handsome

R. sutchuenense

. David said there was no clue at all as to where it came from or when it was planted. In contrast, there are many new beds of species (well budded, sturdy plants) which have been sent down from Edinburgh, and all are from known wild sources. These new beds are the only ones which are watered; the old plants must fend for themselves. David has a staff of only four for all eighty acres.

Among the older rhododendrons we paused to admire were a fine, dense

R. longesquamatum

(not yet in bloom), which "does fine here," and

R. bureavii

. This flowers poorly, he said, but the great leaves and indumentum more than make up for this deficiency.

R. insigne

looked wonderful. With so much to see, we were walking and talking too fast for me to do very much with my camera!

Near Scrape Burn, David pointed out bold patches of bright yellow skunk cabbage,

Lysichitum americanum

, from our Northwest. He told us these were also from F.R.S. Balfour's collecting early in this century. He dug and sent the original plants home to Scotland himself.

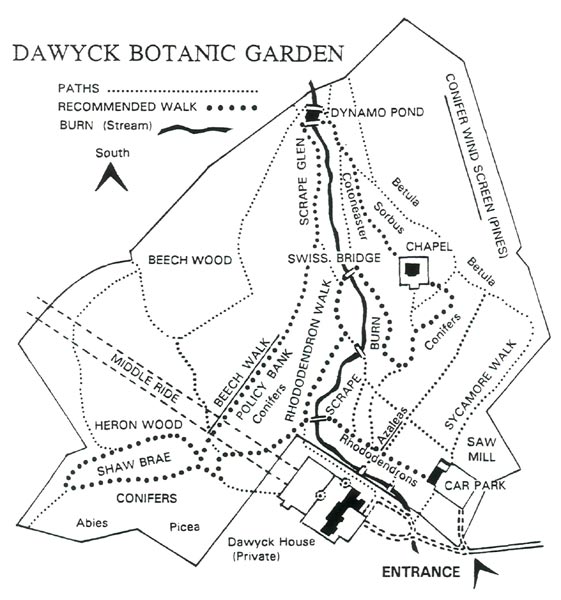

Our guided tour looped via Rhododendron Walk and Beech Walk, then down past the original Dawyck beech, its still-bare branches reaching skyward. By then we were headed back toward the office and decided it was time for lunch. David offered us hot tea, and we brought in our standard picnic fare of oatcakes and cheese. We ate in his office, while pouring over the computer list of plants and the computer location map. David marked one map up for us, in red ink; this is the Recommended Walk you will find on my map. Then, map, notebook and camera in hand, we started out on a more leisurely exploration of the garden on our own.

|

Our first stop was an admiring one by new beds of

R. decorum

,

R. thomsonii

, and

R. oreodoxa

var.

fargesii

, just up the path. We were too early for the bloom, but the buds were fat and promising. At an inviting crosswalk, mounds of deciduous azalea hybrids were banked on the uphill side. Again, we were too early, by at least two weeks, but could imagine the bright display. I noted Exbury 'Hotspur', 'Berryrose' and 'Cecile', among many others. This azalea path leads to some stone steps flanked by elaborate stone urns, encrusted with moss. Standing there, one can look left down to Dawyck House and, right, up a slope of daffodils. We resisted the temptation to go up and returned to David's suggested walk.

We were soon lured off the path again, though, by a bench set on springy moss under some beech trees, with another view down to the faraway house. As yet, I had only photographed a pretty pink

R. orbiculare

hybrid and a very nice deep pink

R. argyrophyllum

ssp.

nankingense

. I was not really disappointed; the garden is spectacular even when not many of the rhododendrons are open. With all the trees and the daffodils, one could only be delighted. We lingered on the bench, enjoying especially the majesty of the great conifers.

David came by with his clinometer, measuring these giants. He had just found the nearest

Sequoiadendron giganteum

(known, for some reason, as Wellingtonia in Britain) to be 120' tall. The conifers at Dawyck do, indeed, deserve constant measuring. At present there are nine trees here which are listed by the Forestry Commission as 'Champion Trees', the tallest in Britain. These are four species of

Abies

, four of

Picea

, and one

Pinus

.

Among other new rhododendron beds we noticed a grouping of Neriiflora; these were all Forrest plants,

R. dichroanthum

ssp.

scyphocalyx

#27063,

R. temenium

var.

temenium

#21734,

R. sanguineum

var.

haemaleum

#19958 and

R. citriniflorum

var.

horaeum

#25901. We could only imagine the orange, crimson and yellow to come.

|

|

R. sanguineum

ssp.

sanguineum

var.

didymoides

Photo from the collection of the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh |

We crossed a small stone bridge over merrily gurgling Scrape Burn. A 'Unique' covered one end of the mossy stone wall, and my favorite little bird, a friendly chaffinch, arrived to sit on the wall and sing to us. One of the mammoth Douglas firs looms beyond, and there are handsome plants of

R. balfourianum

and

R. roxieanum

nearby. We turned right, to follow Rhododendron Walk. This is a lovely, level path which follows Scrape Burn upstream. It is a very quiet place, deep in the trees and with the only sound a soft bubbling of running water.

My next photographs here were of a Taliensia grouping beneath a Japanese stewartia (

Stewartia pseudocamellia

). Its exfoliating red/brown/gray bark is most attractive. The rhododendrons were

R. wightii

,

R. wiltonii

, and

R. traillianum

; I had never seen these before. Although not "showy", they are nice plants with good foliage. The smallish campanulate flowers of

R. wightii

are pale yellow with crimson in the throat, and

R. traillianum

is white, with two touches of rose on the upper lobe. The next plant blooming for my camera was

R. vernicosum

; across the path from it were the first of the garden's many

R. wardii

. There are not many perennials at Dawyck, but along the path are some of the sky-bright blue poppies,

Meconopsis x sheldonii

.

Benches in special places are always irresistible to us. We found one under another shaggy-barked

Sequoiadendron

, surrounded by a bed of unfamiliar ferns. The leathery little species turned out to be

Blechnum pennamarina

. We could have sat there happily for an hour, at least, if our too limited time weren't hurrying by! Instead, we walked on up the burn. A lovely

R. oreodoxa

var.

fargesii

arched above our heads. This is a species familiar to us, but as a shrub, not a veritable tree.

|

|

R. roxieanum

var.

oreonastes

Photo from the collection of the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh |

A handsome mound of

R. williamsianum

marked a cross path, and David's red line directed us to the right, back over the burn. First, though, we studied a bed of varying

R. roxieanum

. The var.

oreonastes

, has very, very narrow linear leaves (some only a quarter of an inch wide and four inches long) with dense, deep orange indumentum. This is another Taliensia and has campanulate white flowers with a spattering of crimson dots. I was rather intrigued to note, upon checking our trusty RHS Handbook, that the Cullen and Chamberlain / Edinburgh Revision doesn't recognize oreonastes as a variety - but this was certainly RBGE's own labeling! Another variety, with wide leaves, is

cucullatum

. I photographed both.

The bridge we next crossed is an interesting one, called the Swiss Bridge. The arch above the burn is high, and stone steps lead up to the center, then down the other side. Our destination was the small chapel at the top of the hill. Sadly, most of the flowers on the upward path had been frosted -

R. calophytum

and

R. thomsonii

among others.

The turn to the chapel is flanked by two more elaborate stone urns, and carpets of bluebells are everywhere (I believe these are now listed as

Scilla nonscripta

, but they are still

Endymion

to me). The sloping lawn here holds a really magnificent array of trees; a glorious weeping

Picea brewerana

was the first to demand attention. Today its wide branches have become a bit squeezed against a bright green, columnar form of the Lawson cypress (

Chamaecyparis lawsoniana

var.

erecta viridis

). Another American nearby is dark and graceful

Chamaecyparis nootkatensis

. Among the conifers are a few maples and some handsome large lindens (

Tilia

), which are inexplicably called limes in Britain. The carpeting underneath adds white

Narcissus

to the bluebells for a lovely tapestry.

The wee gray stone chapel is surrounded by Naesmyth and Balfour gravestones, softened by the years and touched by patterns of silvery lichen. From the glen below comes the faintest murmur of the burn.

We moved onward through a glade of birches; here were Shakespeare's irresistible yellow cowslips (

Primula veris

), and I stooped to photograph a pretty clump. The path led down the hillside to small, still Dynamo Pond. We stood for a while on the bridge and admired a pale pink

R. argyrophyllum

above the water. Beyond the pond, our path took us down Scrape Glen, where there were a few rhododendrons in bloom. I found

R. phaeochrysum

, with smallish white flowers but glossy leaves and good form. To follow David's red ink markings, we veered to the right and up the slope to Beech Walk.

Beech Walk is a long grassy terrace, really, with wee white daisies sprinkled on the green. On the uphill side there are old beeches in stately parade, and downhill the Policy Bank is rich with conifers. I noted a Nikko fir from Japan (

Abies homolepsis

) and a Macedonian pine (

Pinus peuce

), among many, many others. Near the end of Beech Walk a vista, framed by the dark trees, is opened down to the house far below, seen across the lawn and thedaffodils. There are blue hills beyond. (See Middle Ride on the map.)

Our afternoon was rapidly running out; the gardens close at five o'clock. We couldn't add the loop walk through Shaw Brae and Heron Wood, where the ancient silver firs are. Reluctantly, we turned downhill. A last stone stair, marked with round finials faceted like huge gemstones, was moss-encrusted, and there were tiny violets growing in the crevices. We reached the office just in time to thank David, and say goodbye.

I would like to add just a bit about RBGE's plans for the future of Dawyck. G. Broadley sent me his "Report to the Trustees" (1988); in it he assesses the "housekeeping" chores still to be done and defines the various genera slated for study and collection. Of course conifers take the most prominent place, as they comprise the most extensive of the existing plantings. For instance, the Chinese spruces and silver firs are considered "the best surviving collection anywhere", to quote Dr. Page of the Edinburgh Conifer Project. Of very special interest to rhododendron people will be a proposal by Dr. Chamberlain; because of Dawyck's early connection with Wilson seed, he suggests that a comprehensive collection be planted of the rhododendrons collected by E. H. Wilson in China (1889-1911) - fifty-nine species. He believes most would survive here. Among Mr. Broadley's very practical suggestions are the possible building of a visitor's center and a tea room; this would certainly help attract more people. As Dawyck is so close to Edinburgh, it should become an important study and teaching center. On the day of our tour, we seemed to be the only visitors in the garden! Dawyck is much too interesting a garden to be so little known.

We were sorry our happy day of exploration had to end. Driving away, we again passed the black sheep in their green meadow and the gray stone village of Peebles, then reached our inn in time for a pre-dinner glass of sherry before a cherry log fire. I hope very much that we can return to Dawyck someday.

Martha Prince, a member of the New York Chapter, is a writer/artist/photographer and a frequent contributor to the ARS Journal.