Planting the Seed

Donald W. Hyatt

McLean, Virginia

In the fall semester of 1991, I organized a Plant Preservation Club with some students at the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, a magnet school in northern Virginia where I teach computer science. Although interested in preserving all sorts of rare and native plants, we primarily focused our efforts on rhododendrons. With seeds of native azaleas and rhododendrons collected wild in West Virginia which were sent to me by several ARS members and a few hybrid crosses of my own, I began a project to raise rhododendron seedlings.

Initially, I contacted interested ninth graders since they could experience the full gardening cycle: sowing seed, raising plants, and watching them bloom by the end of their four years in high school. I also wanted to stress organic principles and environmental concerns through all phases of our project. With a group of about ten students, I met once or twice each month during that first school year. We planted our seeds in cut-off plastic milk jugs and enclosed containers in clear plastic bags. We then placed these miniature greenhouses in the back of the computer lab under sets of artificial lights which remained on 24 hours a day. Throughout the school year, we watched the rhododendrons grow and transplanted crowded seedlings into other jugs as time and space permitted. One advantage of growing seedlings in these enclosed environments is that they require no care for months at a time, making the project a perfect approach in a busy classroom situation.

When warm weather arrived, we moved most of the plants outside along a northeast wall of an interior courtyard but kept the smaller seedlings back in our computer lab, still enclosed in plastic bags. When rain was not sufficient during summer months, I stopped by to water the container plants and made sure the fluorescent lights were still burning. As winter approached, we mulched the outdoor area with leaves gathered around the campus.

During the next two years, we watered, fertilized, transplanted, and awaited our first flower buds. We also planted more seeds. There were predictable droughts, heat waves, heavy snows, fungus diseases, and insect pests, but we did not spray or try to maintain artificially perfect conditions. Wanting to rely on natural selection to help reduce the numbers, we still had more seedlings than we could manage.

By the end of four years, many of the rhododendron species from West Virginia had started to bloom. There were nice pink forms of

Rhododendron minus

from Doc Tolstead's Top 'O the Hill near Elkins, West Virginia, and fragrant white blossoms of

R. arborescens

grown from seed collected in Tucker County. There were beautiful yellow to orange forms of

R. calendulaceum

from Seneca State Park near the town of Frost, West Virginia. The seedlings of

R. prinophyllum

(syn.

R. roseum

) from Dolly Sods had dwindled in number, but remaining ones seemed vigorous.

Rhododendron periclymenoides

(syn.

R. nudiflorum

) plants grown from seed we collected locally in northern Virginia seemed very happy with our environmental conditions.

Among the hybrid crosses, seedlings of rhododendron ('Scintillation' x 'Disca') were exceptionally robust, and the first one to bloom set three huge buds opening to excellent frilled trusses of luminous soft pink. The cross ('Golden Star' x 'Dexter's Orange') was growing well, and even though plants looked as if they might be yellow, none had set buds yet. Among 50 blooming seedlings of an evergreen azalea cross ('Dream' x 'Nancy of Robinhill'), we noticed remarkable variation. Flowers ranged from white and pale lavender to all shades of pink including blush, rose pink, cerise, and deeper hues which almost approached red. There were single and double forms. Anxious to share the results of our project with the rest of the school, we selected the best seven plants from that cross and set up a display in the main office so that students and faculty could vote on their favorite azaleas. We also encouraged them to suggest possible names should one of the plants prove worthy of naming. A double rose pink with red blotch seemed to be the school favorite, although it reminded me of several other azaleas already on the market. I preferred the large, ruffled, semi-double blush pink with a pale green throat.

By the spring of 1995, it was time to give some of the plants permanent homes. We had been looking for landscape sites around the campus and with approval of the school administration started with a wide planting bed around the perimeter of the parking lot. Although an expanse of asphalt would add to summer heat stress, tall trees on neighboring property would provide some afternoon shade. Anyway, heat tolerance is a very desirable characteristic for plants growing in our region.

|

|

|

|

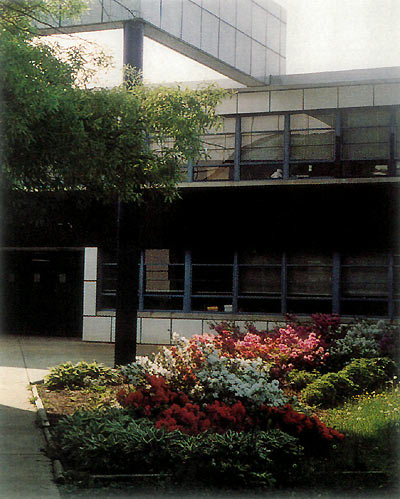

Thomas Jefferson High School for

Science and Technology, main entrance with azaleas and hostas. Photo by Donald W. Hyatt |

Planting around the perimeter of the school parking.

Photo by Donald W. Hyatt |

I enjoyed listening to the students who started this project as they neared their graduation. They reflected on feelings of accomplishment, remembering how tiny the seedlings were when they first germinated, and how big the plants had become. These students are in college now, but there are others who are continuing to plant seeds at Jefferson. Years from now, these alumni will return with pride to view their contribution toward the beautification of our school and community.

Even though my students were planting seeds which might produce some new hardy rhododendrons for our region, I was more gratified to be nurturing the seeds of a future generation of rhododendron enthusiasts. If we expect great gardens, rare plants, and native stands of rhododendrons and azaleas to survive much beyond our own brief existence, it is important to cultivate an appreciation of the genus in the next generation. I encourage others to involve children in their communities with similar projects. We need to plant the seeds of those who will carry on the fine traditions of our American Rhododendron Society.

Don Hyatt is president of the Potomac Valley Chapter.