Studies of Factors Inhibiting the Rooting of Rhododendron Cuttings

By Bernard Thomas Bridgers

Scientific paper No. A384, Contribution No. 2398, of the Maryland Agricultural Experiment Station

Part Two

Combination Wound and Chemical Treatments

ABSTRACT

Factors of inhibition to rooting of rhododendron cuttings were investigated by chemical, environmental, anatomical, and physiological studies.

Tannin analysis were made using various species and varieties, and the rooting response of cuttings subjected to controlled and uncontrolled conditions of temperature, humidity, light, and atmosphere of medium was observed. Cuttings, with and without flower buds and of different ages of growth, were subjected to various wound and chemical treatments. Attempts were made to prevent discoloration at basal ends of cuttings, and cross sections of different ages of stems were observed. Respiration of stem tissue and water absorption of cuttings were studied.

|

|

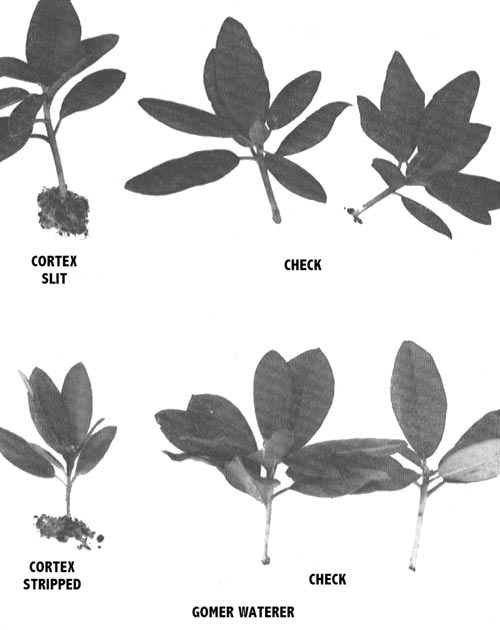

Fig. 1. Typical rooting of cuttings of

Rhododendron catawbiense

'Roseum Elegans'

when subjected to the tripped wound treatment and Hormodin 3 (top row) and unwounded and Hormodin 3 (bottom row). Bridgers photo |

To eliminate the possible inhibitory effect to rooting caused by stem structure, the tissues to the outside of the cambium were interrupted by various methods. Observations from the first experiment indicated that mechanically wounded cuttings without further treatment with root promoting substances rooted slowly as certain catawbiense hybrids treated in such manner showed only slight signs of rooting at end of 12 weeks. Results obtained at the end of 11 weeks after retreatment are shown in Table V.

|

Table V. The Effect of Initial Wound Treatment and Corresponding Wound Retreatment with Hormodin 3 upon the Rooting Response of Various catawbiense hybrids. (Cuttings taken August 10, 1950; retreated November 5, 1950: final data recorded January 20, 1951) |

||||

| Variety Name | Treatment |

Number

of Cuttings |

Average

Rooting Score |

Per Cent

Rooting |

| Gomer Waterer | Unwounded plus Hormodin 3 | 48 | 1.2 | 25.0 |

| Stripped plus Hormodin 3 | 48 | 1.9 | 33.3 | |

| Slit plus Hormodin 3 | 48 | 2.2 | 50.0 | |

| Duchess of Edinburgh | Unwounded plus Hormodin 3 | 48 | 0.9 | 8.3 |

| Stripped plus Hormodin 3 | 48 | 1.3 | 45.8 | |

| Slit plus Hormodin 3 | 48 | 1.7 | 41.7 | |

| Roseum Elegans | Unwounded plus Hormodin 3 | 48 | 1.6 | 33.3 |

| Stripped plus Hormodin 3 | 48 | 2.1 | 54.2 | |

| Slit plus Hormodin 3 | 48 | 2.9 | 66.7 | |

A marked increase in rooting in both heaviness and percent rooting (shown in Figs. 1 and 2) was noticed when the cuttings were wounded and treated with Hormodin 3 powder. This was in accordance with the work of Kruyt (20) who also observed that the treatment with growth promoting substances gave a marked increase in per cent rooting.

|

|

Fig. 2 Rooting response of cuttings of

catawbiense

hybrids showing

the increase in heaviness of rooting when susbjected to various wound treatments in combination with Hormodin 3. Bridgers photo |

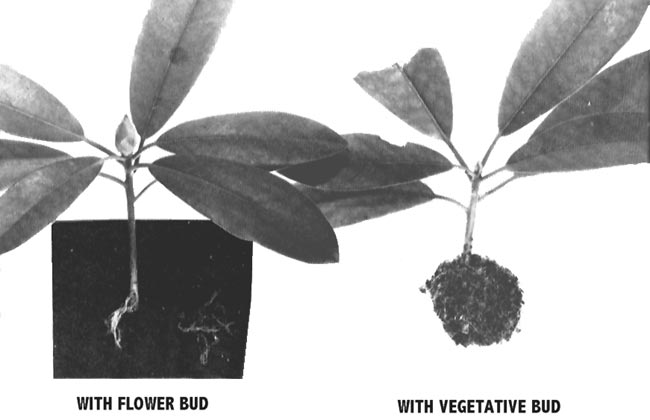

The wound treatment; produced a heavier and a better distributed root system than the unwounded, and extreme basal callusing and subsequent weak rooting was eliminated. Hubert, Rappaport, and Beke (15) have reported in agreement. Data resulting from a study of the influence of age of wood and presence of flower buds on the rooting response of cuttings of R. maximum roseum which were treated with various wound and chemical treatments are shown in Table VI. It was apparent that cuttings taken at the junction of 1 and 2 year wood, with or without flower buds, rooted heavier and a greater per cent rooted than cuttings made of 2 year wood. The rooting response of cuttings taken without flower buds, cut at the junction of 1 and 2 year growth, subjected to the stripped wound treatment, and with or without the wax dip, was greater than similar cuttings treated in the same manner but with flower buds. Working with various rhododendron species, Kemp (17) also reported in agreement that shoots with vegetative buds were superior in rooting to those with flower buds. The apparent detrimental effect of flower buds on root development may be seen in Fig. 3.

|

|

Fig. 3. Comparison of rooting response of

Rhododendron maximum roseum

cuttings as

influenced by the presence of flower or vegetative buds. Bridgers photo |

| TABLE VI. Rooting Response of Rhododendron maximum roseum Cuttings as Influenced by Age of Wood, Presence of Flower Buds, and Various Wound and Chemical Treatments (Cuttings taken November 12, 1950: final data recorded February 6, 1951). | ||||

| Treatment | Type of Wood |

Number

of Cuttings |

Average

Rooting Score |

Percent

Rooting |

| With Flower Buds | ||||

| Untreated | Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 12 | 1.3 | 25.0 | |

| 2 year wood | 12 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| Stripped | Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 12 | 1.6 | 16.7 | |

| 2 year wood | 12 | 1.0 | 8.3 | |

| Stripped, then Waxed | Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 12 | 1.0 | 8.3 | |

| 2 year wood | 12 | 0.5 | 8.3 | |

| Without Flower Buds | ||||

| Untreated | Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 15 | 1.3 | 13.3 | |

| 2 year wood | 15 | 1.0 | 6.6 | |

| Stripped | Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 15 | 2.4 | 33.3 | |

| 2 year wood | 15 | 0.2 | 6.6 | |

| Stripped, then Waxed | Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 15 | 2.1 | 26.4 | |

| 2 year wood | 15 | 1.0 | 0 | |

| Stripped, Hormodin 3 | Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 15 | 2.5 | 40.0 | |

| 2 year wood | 15 | 1.4 | 13.3 | |

| Stripped, Hormodin 3 then Waxed | Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 15 | 3.0 | 46.7 | |

| 2 year wood | 15 | 1.0 | 6.6 | |

| Stripped, Hormodin 3 plus Fermate (3:1) | Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 15 | 3.4 | 60.0 | |

| 2 year wood | 15 | 1.8 | 0 | |

|

Stripped, Hormodin 3 plus Fermate (3:1), then Waxed |

Cut at Junction | |||

| 1 and 2 year wood | 15 | 3.8 | 60.0 | |

| 2 year wood | 15 | 1.5 | 0 | |

When cuttings without flower buds, taken at the junction of 1 and 2 year wood, were subjected to Hormodin 3 in combination with the stripped wound treatment, with or without the wax treatment, there was an increase in both heaviness and per cent rooting. Furthermore, there was a similar increase in response obtained when cuttings made in the same manner but treated with a combination of Hormodin 3 and Fermate, prepared in a 3 to 1 ratio, with or without wax. There was a decided increase in average rooting score when Fermate and wax were used as compared to Hormodin 3 treatment alone.

A study was made to compare various wound and chemical treatments on the rooting response in per cent root ing and average rooting score of cuttings of R. 'Watereri'. From the data presented in Table VII and the analysis in Table VIII, the stripped and sliced wound methods were significantly better than the slit. There was no significant difference between the chemical treatments, but each of these treatments was highly significant to the untreated.

| TABLE VII. The Effect on Per Cent Rooting of Rhododendron 'Watereri' Wils. Cuttings Subjected to Various Wound and Chemical Treatments (Cuttings taken February 18, 1951; final data recorded June 1, 1951). | ||||||

|

Method

of Wounding |

Hormodin 3 plus

Fermate (3:1) |

Hormodin 3 plus

Fermate (3:1), then Waxed |

Untreated |

Indolebutyric

Acid (100 mg/1, 24 hr) |

Indolebutyric Acid

(100 mg/1, 24 hr) then Waxed |

Method

of Wounding Average |

| TREATMENT | ||||||

| Slit | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| Stripped | 3.3 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.4 |

| Sliced | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.4 |

| Treatment Average | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 2.1 | |

| LEAST SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCE REQUIREMENT | ||||||

| Method of Wounding: 5%-0.7 | ||||||

| Treatment 5%-0.9 | ||||||

| l%-1.2 | ||||||

| TABLE VIII. Analysis of Variance of Percent Rooting of Rhododendron 'Watereri' Wils. Cuttings Subjected to Various Wound and Chemical Treatments (Cuttings taken February 18, 1951; final data recorded June 1951) | |||

| Source of Variation | D/F | Variance | F |

| Method of Wounding | 2 | 3.49 | 3.71 * |

| Treatment | 4 | 5.13 | 5.46 ** |

| Replicate | 2 | 0.83 | 0.88 |

| Method of Wounding x Treatment | 8 | 1.77 | 1.88 |

| Error | 28 | 0.94 | |

| Total | 44 | ||

|

* Significant at 5% |

|||

|

** Significant at 1% |

|||

When heaviness of rooting was considered, (Tables IX and X.) the stripped and sliced wound methods were noted to be highly significant to the slit. Furthermore, a study of the various chemical treatments showed that Hormodin 3 and Fermate, at a ratio of 3 to 1, with the wax was highly significant to all other treatments. Treatment by solution immersion for 24 hours using indolebutyric acid at a concentration of 100 milligrams per liter was highly significant to the same treatment with wax. Results from all chemical treatments were highly significant to those of the untreated cuttings.

| TABLE IX. The Effect on Average Rooting Score of Rhododendron 'Watereri' Wils. Cuttings Subjected to Various Wound and Chemical Treatments (Cuttings taken February 18, 1951; final data recorded June 1, 1951). | ||||||

|

Method of

Wounding |

Hormodin 3 plus

Fermate (3:1) |

Hormodin 3 plus

Fermate 3:1), then Waxed |

Untreated |

Indolebutyric

Acid (100 mg/1, 24hr) |

Indolebutyric

Acid (100 mg/1, 24 hr) then Waxed |

Method

of Wounding Average |

| Slit | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| Stripped | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| Sliced | 2.8 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Treatment Aveg. | 2.2 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 1.6 | |

| LEAST SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCE REQUIREMENT | ||||||

| Method of Wounding: 5%- 0.3 | ||||||

| 1%- 0.4 | ||||||

| Treatment: 5 % - 0.2 | ||||||

|

1% -0.3 |

||||||

| Method of Wounding x Treatment: 5%- 1.0 | ||||||

| 1% - 1.3 | ||||||

| TABLE X. Analysis of Variance of Average Rooting Score of Rhododendron 'Watereri' Wils. Cuttings Subjected to Various Wound and Chemical Treatments (Cuttings taken February 18, 1951; final data recorded June 1, 1951). | |||

| Source of Variation | D/F | Variance | F |

| Method of Wounding | 2 | 2.72 | 15.1 ** |

| Treatment | 4 | 4.45 | 24.7 ** |

| Replicate | 2 | 0.19 | 1.1 |

| Method of Wounding x Treatment | 8 | 0.74 | 4.1 ** |

| Error | 28 | 0.18 | |

| Total | 44 | ||

| ** Significant at 1% | |||

In the interaction of methods of wounding and chemical treatments, there was noted that with the stripped and sliced methods, Hormodin 3 plus Fermate, with or without wax, was highly significant to the same chemical treatment when used with the slit method.

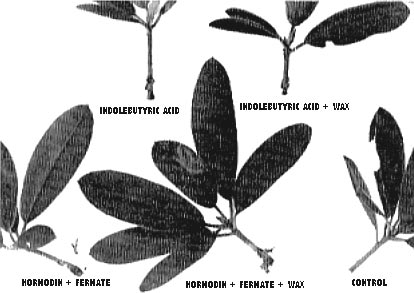

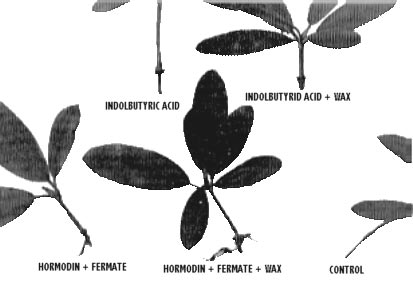

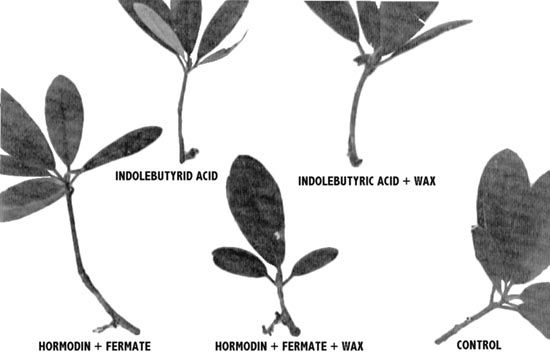

A comparison of early root development of the various wound and chemical treatments may be seen in Figs. 4, 5 and 6. In the majority of cuttings observed, the chemical treatment using Hormodin 3 and Fermate (3:1) with wax was found to produce roots earlier than the other treatments. This was believed to be the explanation as to the reason this treatment was found significantly better, when heaviness of rooting was considered, than the other treatments.

|

|

Fig. 4. Rooting response at the end of 8 weeks of Rhododendron

'Watereri' Wils. cuttings subjected to the sliced wound treat- and treated with Hormodin 3 and Fermate (3:1) or indolebutyric acid, solution immersion treatment 24 hours, 100 milligrams per liter, with or without wax. Bridgers photo |

|

|

Fig. 5. Rooting response at the end of 8 weeks of Rhododendron

'Watereri' Wils. cuttings subjected to the stripped wound treatment and treated with Hormodin 3 and Fermate (3:1) or indolebutyric acid, solution immersion treatment 24 hours, 100 milligrams per liter, with or without wax. Bridgers photo |

|

|

Fig. 6. Rooting response at the end of 8 weeks of Rhododendron

'Watereri' Wils. cuttings subject to the slit wound treatment and treated with Hormodin 3 and Fermate (3:1) or indole- butyric acid, solution treatment 24 hours, 100 milligrams per liter, with or without wax. Bridgers photo |

A further comparison of the sliced and stripped wound treatments with the various chemical treatments was studied using cuttings of R. catawbiense 'Roseum Elegans'. Data, based on per cent rooting, (Tables XI and XII) showed the sliced method was significant to the stripped.

| TABLE XI. The Effect on Per Cent Rooting of Rhododendron catawbiense 'Roseum Elegans' Cuttings Subjected to Various Wound and Chemical Treatments (Cuttings taken March 21, 1951; final data recorded June 15, 1951). | ||||||

|

Method

of Wounding |

Hormodin 3

plus Fermate (3:1) |

Hormodin 3

plus Fermate (3:1), then Waxed |

Acid |

Indolebutyric

Acid (100 mg/1, 24 hr) |

Indolebutyric

Acid (100 mg/1, 24 hr) then Waxed |

Method

of Wounding Average |

|

Sliced |

5.7 | 6.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 3.2 |

| Stripped | 4.0 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0 | 1.9 |

| Treatment Average | 4.9 | 5.3 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | |

| LEAST SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCE REQUIREMENT | ||||||

| Method of Wounding: 5%-1.1 | ||||||

| Treatment: 5%-1.8 | ||||||

| 1 % - 2.4 | ||||||

| TABLE XII. Analysis of Variance of Per Cent Rooting of Rhododendron catawbiense 'Roseum Elegans' Cuttings Subjected to Various Wound and Chemical Treatments (Cuttings taken March 1, 1951; final data recorded June 15, 1951). | |||

| Source of Variation | D/F | Variance | F |

| Method of Wounding | 1 | 12.03 | 5.90 * |

| Treatment | 4 | 32.05 | 15.71 ** |

| Replicate | 2 | 0.44 | 2.16 |

| Method of Wounding x Treatment | 3 | 0.81 | 0.40 |

| Error | 19 | 2.04 | |

| Total | 29 | ||

| * Significant at 5% | |||

| ** Significant at 1% | |||

There was no significant difference between the Hormodin 3 and Fermate when used with or without the wax: however, these treatmnts were highly significant to treatments using indolebutyric acid, either alone or with wax.

Considering the rooting response in terms of heaviness of rooting, (Figs. 5 and 6) the sliced wound method was highly significant to the stripped. In using wax with Hormodin 3 and Fermate, there was a significant difference over the unwaxed, and both of these treatments were highly significant to the indolebutyric acid treatments. There was no significant difference between the untreated cuttings and those treated with indolebutyric acid.

From the results it was concluded that the stripped and sliced wound methods were superior to the slit, and the sliced method was superior to the stripped. Chemically treating with Hormodin 3 and Fermate (3:1) and using the wax dip appeared to be the best treatment.

Apparently there was a toxic effect to cuttings when treated by solution immersion for 24 hours with indolebutyric acid at 100 milligrams per liter. Cuttings of

R. catawbiense

'Roseum Elegans' showed approximately 90 per cent fatality when treated in this manner. An example, of this toxicity may be seen in Fig. 7. Similar observations (15) were reported concerning wounded cuttings of

Prunus sinensis

.

|

|

Fig. 7. The apparent toxic effect as shown by a cutting of

Rhododendron catawbiense

'Roseum Elegans' when treated with indolebutyric acid, solution immersion treatment 24 hours, 100 milligrams per liter. Injured cutting to left, untreated cutting to the right. Bridgers photo |

| TABLE XIV. Analysis of Variance of Average Rooting Score of Rhododendron catawbiense 'Roseum Elegans' Cuttings Subjected to Various Wound and Chemical Treatments (Cuttings taken March 21, 1951; final data recorded June 15, 1951). | |||

| Source of Variation | D/F | Variance | F |

| Method of Wounding | 1 | 1.72 | 9.53 ** |

| Treatment | 4 | 7.99 | 44.27 ** |

| Replicate | 2 | 0.35 | 1.94 |

| Method of Wounding x Treatment | 3 | 0.14 | 0.78 |

| Error | 19 | 0.18 | |

| Total | 29 | ||

| ** Significant at 1% | |||

| TABLE XIII. The Effect on Average Rooting Score of Rhododendron catawbiense 'Roseum Elegans' Cuttings Subjected to Various Wound and Chemical Treatments (Cuttings taken March 21, 1951; final data recorded June 15, 1951) | ||||||

|

Method

of Wounding |

Hormodin 3

plus Fermate (3:1) |

Hormodin 3

plus Fermate (3:1) then Waxed |

Untreated |

Indobutyric

Acid (100 mg/1, 24 hr) |

Indobutyric

Acid (100 mg/1, 24 hr) then Waxed |

Method

of Wounding Average |

| Sliced | 2.2 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.6 |

| Stripped | 2.7 | 2.9 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0 | 1.2 |

| Treatment Average | 2.5 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | |

| LEAST SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCE REQUIREMENT | ||||||

| Method of Wounding 5%-0.3 | ||||||

| 1%- 0.4 | ||||||

| Treatment: 5%-0.5 | ||||||

| 1%-0.7 | ||||||

PHYSIOLOGICAL STUDIES

Wounding of the stem by different methods has appeared throughout the investigation to be beneficial in both heaviness and per cent rooting, and the wax treatments have been advantageous in like manner. Certain physiological studies were made in order to obtain a possible explanation for the behavior of these treatments.

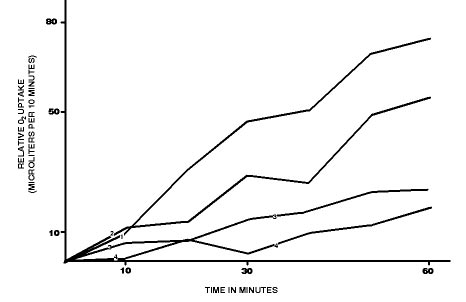

|

|

Respiration of wounded and unwounded stem tissue of

R. maximum

L

as measured by relative oxygen uptake in micro liters per 10 minutes. (Determination made July 3, 1951) Bridgers graph |

|

|

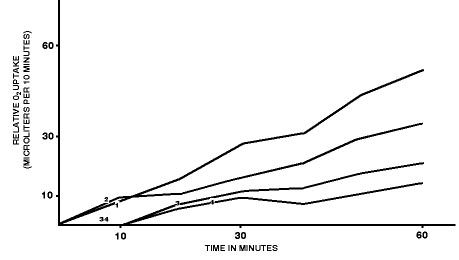

|

|

Respiration of wounded and unwounded waxed stem tissue of

R. maximum L as measured by relative oxygen uptake in micro liters per 10 minutes. (Determination made July 3, 1951) 1. stripped, 2. sliced, 3. slit, 4. unwounded Bridgers graph |

A respiration study of excised portions of the stems, as shown in Figure 8, revealed that wounding greatly increased respiration. The stripped method gave the greatest increase. and the sliced method showed a decided increase over the slit.

When the stem portions were completely waxed (Fig. 9) there was a definite decrease in respiration, which is in agreement with Platenius (22) who used "Brytene" on various vegetables. The data, however, showed the same general trend of respiration in that unwounded tissue used less oxygen, followed by wound methods of slit, sliced, and stripped in increasing order.

The increase in respiration caused by wounding was believed to be explained by the work of Wiesner, as reported by Bonner and English (4), which showed that wounding plant tissue caused a resumption of meristematic activity of cells apparently mature. They concluded that when plant tissue was injured substances were formed or liberated which were capable of causing adjacent uninjured cells to resume greater activity.

Day (8) showed that wounding cuttings of Bartlett pear increased water absorption and postulated that this might be a reason for an increase in rooting response. An increase, as shown in Table XV, was also observed with wounded cuttings of

R. maximum

. When cuttings, with or without wax, were wounded by the slit method there was an increase in moisture uptake over the unwounded; and both the sliced and stripped treatments, with or without wax, showed a decided gain over the slit. The wax treatments showed no appreciable effect.

Interrupting the epidermal layer, previously described, and exposing tissues of the cambium region to direct contact with water was believed to be an explanation for these observations. Since the wax was water soluble its effect on water uptake would appear to be negligible.

It was believed by the author that increased respiration which resulted from wounding the cutting brought about greater activity in the meristematic tissue, and increased water absorption due to wounding was beneficial in maintaining turgidity in the cutting. Therefore, the beneficial effects in rooting response obtained by wounding the cuttings might be explained by increased respiration and water absorption.

An explanation for the increase in heaviness of rooting often noted by the wax treatment was not offered.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

To determine the causal factors inhibiting the rooting of rhododendron cuttings various chemical, environmental, anatomical, and physiological studies were performed.

Component stem parts of various species and varieties were quantitatively analyzed for tannins, and a possible correlation between ease of rooting and tannin content was investigated. Attempts were made to prevent the discoloration at basal ends of cuttings by means of treatments using citric acid and wax.

Cuttings were rooted under changing and controlled conditions of temperature, humidity, and light. In another investigation the atmosphere of the rooting medium was varied by using normal, high, and low oxygen concentrations.

Cross sections of stems were observed and a comparison between the structure of 1 year and other ages of growth was made.

Based on the foregoing study, experiments were performed in which cuttings of various hybrids, with and without flower buds and of different ages of growth, were subjected to various wound treatments and these treatments in combination with various chemical treatments.

Physiological studies consisted of measurement of respiration of excised d portions of stems and water absorption of wounded and waxed cuttings.

From the results of these investigations the following conclusions may be made.

- The greatest concentration of tannins was found in the 1 year old stem, followed, in descending order, by bark of 1 year stem, leaf, 2 year stem, petiole, 2 year bark, flower and vegetative buds, and wood. Furthermore, there was no correlation observed between tannin content of the cuttings and ease of rooting.

- There were no consistent differences in rooting response when cuttings were subjected to controlled or uncontrolled conditions of temperature, humidity, and light. Increasing oxygen concentration of the atmosphere in the rooting medium resulted in heavier root systems and higher per cent rooting than when normal and low oxygen concentrations were used; low oxygen concentration definitely increased rooting response.

- Differences in structure of 1 year and older stems were not observed except the width of tissues from the epidermis to the cambium decreased with age. The heavily cutinized epidermal layer was believed to be a possible inhibitory factor in rooting.

- Rooting response was greater when cutting 3 were taken at the junction of 1 and 2 year wood as compared to 2 year wood. Flower buds on cuttings seemed to inhibit rooting.

- Discoloration at the basal ends of cuttings was higher in wounded cuttings than in unwounded. Treatment with citric acid and wax was inconsistent in prevention.

- The stripped and sliced methods of wounding produced a greater rooting response than the slit method.

- Root promoting substances greatly increased the rooting response of cuttings. A combination of Hormodin 3 and Fermate, ratio 3 to 1, gave an increase in both heaviness and per cent rooting as compared to Hormodin 3 alone; there was an additional increase in heaviness of rooting when wax was used in combination with Hormodin 3 and Fermate.

- Treatment of cuttings with Hormodin 3 and Fermate, ratio 3 to 1, produced a greater rooting response in both heaviness and per cent rooting than when indolebutyric acid, solution immersion treatment for 24 hours with 100 milligrams per liter, was used.

- Respiration of stem tissue was increased by wound treatments.

- Cuttings subjected to wound treatments absorbed more water than unwounded cuttings.

- The greatest rooting response in terms of both heaviness and per cent rooting was obtained when cuttings of 1 year wood without flower buds were subjected to the sliced wound treatment, treated with Hormodin 3 and Fermate (3:1), then waxed, and rooted in a medium of half sand and half peat with a normal atmosphere and under uncontrolled conditions of light, temperature, and humidity.

From the data the following conclusions may be drawn:

- No correlation was found between tannin content and ease of rooting.

- Enriched oxygen content of rooting medium improved rooting response; however, no consistent differences were observed when cuttings were subjected to controlled and uncontrolled light, temperature, and humidity.

- Stem anatomy showed a heavily cutinized epidermal layer.

- Flower buds and 2 year wood appeared detrimental to rooting.

- Discoloration at the basal ends of cuttings was higher in wounded cuttings than in unwounded.

- Stripped and sliced wound methods produced a greater rooting response than the slit method.

- Root promoting substances increased rooting response. Hormodin 3 and Fermate (3:1) appeared to give better results than Hormodin 3 alone; when these treatments were used with wax, an increase in heaviness of rooting resulted.

- Respiration of stem tissue was increased by wound treatments.

- Wounded cuttings absorbed more water than unwounded cuttings.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Anonymous. Rhododendrons from cuttings , American Rhododendron Soc. Quart. Bul., 9: 4-7, 1951

- Association of Official Agricultural Chemists, Official and Tentative Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists , Washington, D.C. 1945.

- Boch, Robert. Wound healing in higher plants , Bot. Rev., 7: 110-147, 1941

- Bonner, James and James English Jr. A Chemical and physiological study of trauniatin, a plant wound hormone , Plant Physiol., 13:331-348, 1938

- Chadwick, L. C. and William E. Gunesch, Propagation of R. 'Cunningham's White' , Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci., 34: 607-611, 1937

- Clarke, Ira D. and J. S. Rogers, Tannin content and other characteristics of native sumac in relation to its value as a commercial source of tannin , U. S. Dept. Agr. Tech. Bul. 986

- Cox, E. M. and Francis Stoker, Stimulation of root formation in cuttings by artificial hormones , New Flora and Silva, 10: 65-69, 1937

- Day, Leonard H. Is the increased rooting of wounded cuttings sometimes due to water absorption , Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci., 9: 350-352, 1932

- Doak, B. W., The effect of various nitrogenous compounds on rooting of rhododendron cuttings with naphthalenacetic acid , New Zealand Jour. Sci. Techn., 21: 336A-343A, 1940>

- Doran, William L. The propagation of some trees and shrubs by cuttings , Mass. Agr. Exp. Sta. Bul., 382, 1941

- Eckstein, Meyer Michael, Factors inhibiting the rooting of rhododendron cuttings , M.Sci. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, Md., 1950

- Eley, C., Concerning stocks on which to graft rhododendrons , Rhododendron Soc. Notes, 2: 110-111, 1922>

- Goulden, C. H. Methods of Statistical Analysis , John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1939

- Hanger, Francis. The cultivation of the rhododendrons , Jour. Royal Hort. Soc., 70: 355-362, 1945

- Hubert, B. J. Rappaport, and A. Beke, Onderzoekingen over de beworteling van stekken , Mededeel. Landbouwhoogeschool., Cent. 7: 3103, 1939. (With English Summary)

- Johanscn, D. A. Plant Microtechnique , McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1940

- Kemp, E. E. Some aspects of plant propagation by cuttings , Jour. Royal Hort. Soc., 73: 291-305, 1948

- Kirkpatrick, Henry. Effect of indolebutyric acid on the rooting response of evergreens , Amer. Nurseryman, 71(8) : 9-12, 1940

- Knight, F. P. Propagation of rhododendrons by cuttings , Gard. Chron., 85 (2198): 99-100, 1929.

- Kruyt, W., Het stekken van Rhododendron keuze van het juiste medium en het gebruik van groer stofferi , Med. Direct. Trinbow., 7: 255-271, 1946 (With English Summary)

- Nearing G. G. and Charles H. Connor, Rhododendrons from cuttings , N. J. Agr. Exp. Sta. Bul. 666, 1939t>

- Platenius, Hans, Wax emulsions for vegetables , Cornell Univ. Agr. Exp. Sta. Bul., 723, 1939

- Pridham, A., M. S. Factors in rooting and growth, of young plants , Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci., 40: 579-584, 1942

- Schols, J. Vliv indol-3-octove kyseliny na zakrenovani letnich risku nekterych okrasnych drevin , Ceskoslov. Akad. Zemedel. Shorn., 12: 648-659, 1937 (With English Summary)

- Scott, Wilfred W., Standard Methods of Chemical Analysis. Vol. 11 , D. Van Nostrand Co., New York, 5th Edition, 1939

- Skinner, Henry T. Rooting response of azaleas and other ericaceous plants to auxin treatments , Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci., 35: 830-838, 7 937

- ____________ Further observations on the propagation of rhododendrons and azaleas by stem and leaf-bud cuttings , Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci., 37: 1013-1018, 1939

- __________, Propagation of rhododendrons and azaleas , Plants and Gard., 5: 13-17, 1919

- Small, James. Propagation by cuttings ht acidic media , Gard. Chron., 73 (1897): 2-14-2-15, 1923>

- Stoutemyer, V. T., Humidification and the rooting of greenwood cuttings of difficult plants ,Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci., 40: 301-304, 1942

- ________and A. W. Close, Rooting cuttings and germintinating seeds under cold cathode lighting , Proc. American Sec. Hort. Sci., 48: 309-325, 1946

- Thimann, Kenneth V. and Jane Behnke-Rogers, The Use of Auxins in the Rooting of Woody Cuttings Harvard Forest, Petersham, Mass., 1950

- Umbriet, W. W., R. H. Burris, and I. F. Stauffer, Manometric Techniques and Related Methods for the Study of Tissue Metabolism , Burgess Pub. Co., Minneapolis, 1915

- Wells, James F. Propagation of hybrid rhododendrons , Amer. Nurseryman, 91(2): 16-18, 1949

- Zimmerman P. W. Oxygen requirements for root growth of cuttings in water , Amer. Jour. Bot., 17: 812-861, 1930

- _________and A. E. Hitchcock, Comparative activity of root-inducting substances and methods for treating cuttings , Contri. Boyce Thompson Inst., 10: 161-480, 1939