The Arnold Arboretum

Donald Wyman

Horticulturist, Arnold Arboretum

|

|

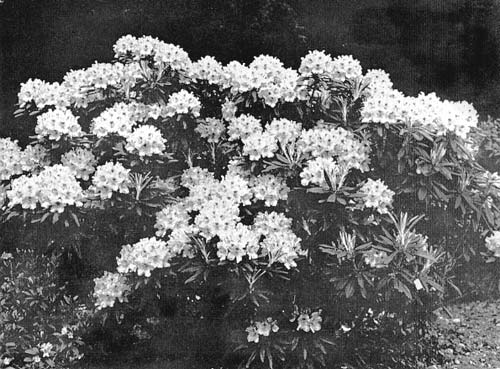

Fig. 15.

R. smirnowii

in the Arnold Arboretum

Arnold Arboretum photo |

The Arnold Arboretum was established in 1872 as a "museum founded and carried on to increase the knowledge of trees." During the intervening years it has been a leader in the dissemination of knowledge concerning ornamental woody plants not only for this country, but for all the northern temperate regions of the world, as well. James Arnold, for whom the Arboretum is named, left a small proportion of his fortune acquired as a New Bedford shipping merchant "to George B. Emerson, John James Dixwell and Francis E. Parker, Esqs., of Boston, in trust: to be by them applied for the promotion of Agricultural or Horticultural improvement, or other Philosophical, or Philanthropic purposes at their discretion." The trustees of his will decided to establish a "tree growing garden." At the time, little was known about the specific requirements of such a unique place, but with this money as a backlog (the income from the endowment at first amounted to about $3000 a year), Harvard University started this now world-famous institution.

Today it is controlled by the President and Fellows of Harvard University, acting as trustees under the will of James Arnold. It is financed entirely from endowment income and from annual gifts for immediate use. The City of Boston owns the land and has leased it to Harvard University for use by the Arnold Arboretum for 999 years at a rental fee of one dollar a year. The city of Boston polices the grounds, maintains the roads and walks and the fence surrounding it, but the Arnold Arboretum, under the trusteeship of Harvard University, maintains the grounds, buildings, herbarium and library. The present staff includes 25 individuals exclusive of grounds crew and office help.

Nearly 6,000 species, varieties and clones of woody plants are growing within its borders at present. Its library today, containing over 51,000 books and 18,000 pamphlets, is probably the best special collection of books on woody plants outside the British Museum, and its world-famous herbarium contains over 726,000 specimens at the present time.

Because of the reputation it has earned in the past, it is now one of the leading botanical and horticultural centers of scientific study and experimentation dealing with woody plants. The publications of its staff members have been accepted as basic by botanists and horticulturists throughout the world.

Early History

In March, 1872, Harvard University set aside 125 acres of the Bussey Farm for the new Arboretum. From time to time other tracts of land were added until the total area today is 265 acres in Jamaica Plain, with an additional 100 acres in Weston, thirteen miles away. As only a small part of the potential number of specimens which might be expected to withstand the climate were at that time to be found in any collection, it was necessary to go outside of North America to the far corners of the earth to procure the thousands of exotic plants which make the Arboretum an important scientific station. The search, which still continues, has included every country in Europe, the Caucasus, Eastern Siberia, China, Korea, Japan, Formosa, Australia, Indo-Malaysia and Africa from the equator south.

In November, 1873, Professor Sargent, then thirty-two years of age and Director of the Harvard Botanic Garden, was appointed Director of the Arnold Arboretum. Under the terms of the Arnold will, which set apart two-thirds of the income from the bequest to accumulate until the fund reached $150,000, he had only $3,000 a year with which to convert a farm, partly covered with native trees, into a scientific tree station. The property had excellent possibilities, with several hills and meadows, a brook, small ponds, a rocky cliff and a grove of splendid native hemlock, but there was a great need of cultivation. The work of forming a nursery was begun at once, greenhouses being available for the propagation of the few plants which could at that time be found in the vicinity.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., the noted landscape architect, proposed an idea for making substantial improvements despite the small budget and his proposal was finally accepted. Mr. Olmsted was planning a park system for Boston at the time, and he suggested the possibility of making the Arboretum's land part of the system, the city to build its roads and provide police protection.

Thus the City of Boston took title to the lands of the Arboretum in December, 1882, leasing the whole tract to the President and Fellows of Harvard for a thousand years, at a rental of one dollar a year, "and so on from time to time forever." The Arboretum received all the advantages of perpetual, tax-free ownership of the land and in return, the University agreed to open the Arboretum to the public from sunrise to sunset during every day in the year, while reserving entire control of the grounds with the exception of the drives and walks.

The Contribution of Plant Hunters

In 1877 came the first opportunity to obtain American plants not then in cultivation. when Sargent was commissioned by the Federal government to prepare a report on the forests and forest wealth of the nation. He traveled into every wooded region from the Atlantic to the Pacific and chose able assistants from various parts of the country. A number of these assistants continued to supply seeds and specimens and secured for the Arboretum information about the trees and shrubs in their native habitat. Close contact with all the important European and American botanic gardens and nurseries enabled Sargent to exchange plants and obtain many additions to the garden. The first direct consignment of seeds from Eastern Asia, sent from the Agricultural College at Sapporo, in northern Japan, reached the Arboretum in December, 1878. Since then, it has assembled a notable collection of Oriental trees and shrubs, many of the most ornamental coming as the result of the travels of Ernest Henry Wilson, an Arboretum staff member from 1906 until his death in 1930. Today, correspondents from all over the world are still sending in plant material, some of which is new to America.

Simultaneously with the formation of the living collections, Sargent built up a rich botanical library and a large herbarium. Besides being a storehouse of scientific knowledge, the Arboretum was becoming a research laboratory for experiments with decided commercial value. In the scientific knowledge of landscape architecture, as well as of timber production in the United States, the Arboretum plays an important part, for here the habits of more kinds of trees can be studied than anywhere else in the country.

The Herbarium

The extremely valuable herbarium of the Arnold Arboretum is justly famous in its own right. It contains over 726,000 specimens at the present time, and has always been the reference source on which most of the many scientific publications of the Arboretum have been based. It is without question the most outstanding herbarium of ornamental woody plants in the United States and is among the few best in the world. All the invaluable collections of Wilson, Sargent, Rehder and many another are well represented here. It is from this collection of herbarium specimens that it has been possible to accurately identify plants from all over the northern temperate regions of the world. "A Monograph of Azaleas" by Ernest Henry Wilson and Alfred Rehder, published by the Arnold Arboretum in 1921 and still used as a valued reference, is only one of the many reference publications which have resulted from studies in this world-famous collection of living plants and such an extremely valuable and complete herbarium. One augments the other and, together with the library, they make it possible for staff and students to do here some of the basic research dealing with ornamental woody plants.

Introductions of the Arnold Arboretum

During its 89 years of existence, the Arnold Arboretum has introduced well over 3000 woody plants new to this country, some of them never before grown in gardens anywhere in the world. A majority of these introductions, of course, came as the result of trips to Japan and China taken by E. H. Wilson and the first Director, Charles Sprague Sargent, both of whom took several trips at the turn of the century to the Orient and sent home seeds and plants of outstanding ornamental merit.

It is hard to believe that a plant as common as the Japanese Barberry was once one of the "new" and "rare" plants grown in the nurseries of the Arnold Arboretum, yet such is the case. Since it was introduced, this plant has proved its usefulness, so much so that it is one of the most common shrubs in our gardens today.

Some of the plants, like the hardy strain of the Cedar of Lebanon (

Cedrus libani

), are the result of particular missions. In this case, the Cedar of Lebanon grown in the warmer parts of the United States never proved hardy under New England conditions, so Professor Sargent commissioned a special trip of collectors in Asia Minor to collect seeds from trees growing naturally at their northernmost source. This was clone in the Anti-Taurus and Taurus mountain ranges and trees grown from these seeds have proved perfect1y hardy under Arnold Arboretum conditions.

The introduction of the Dawn Redwood (

Metasequoia glyptostroboides

) by the Arnold Arboretum in 1948 makes a fascinating story. This plant, supposed to have been extinct for millions of years, was suddenly found, compared with fossil material and, what is most important, distributed to all corners of the earth by the Arnold Arboretum.

In other cases, the collection of seeds of new plants has been merely a happy coincidence, as was the case of

Kolkwitzia amabilis

. E. H. Wilson saw a plant in fruit which was unknown to him. He collected some of the seeds and when the plants were grown in the Arnold Arboretum from this original collection, he was agreeably surprised to see the floriferous and highly ornamental plant later named the Beautybush.

Still other plants are the result of accident. The beautiful 'Arnold' and 'Dorothea' Crab Apples were merely chance seedlings found growing in the Arboretum and at flowering time their value was noted.

Rhododendron obtusum arnoldianum

is another beautiful example of a chance seedling growing actually as a weed among other supposedly more valued plants, but when it bloomed, its true worth was quickly noted and, since being introduced, it has proved a popular azalea in many nurseries.

More recently, many new plants have occurred as the result of scientific plant breeding done at the Arnold Arboretum.

Prunus

'Hally Jolivette,'

Forsythia

'Beatrix Farrand,' F. 'Karl Sax,' F. 'Arnold Dwarf,'

Malus

'Henrietta Crosby,' M. 'Henry F. DuPont,' and M. 'Blanche Ames' are only a few. These have all been introduced to the trade in this country and abroad, so that home owners and plantsmen in general can eventually obtain them for ornamental planting.

Readers of the Quarterly Bulletin of the American Rhododendron Society will be interested in knowing that the Arboretum has been responsible for introducing into this country many of the rhododendron species and botanical varieties now being grown. Only a few of the more than 75 such introductions are the following:

| R. albrechtii | R. keiskei | R. semibarbatum |

| R. decorum | R. mucronulatum | R. serrulatum |

| R. discolor | R. obtusum japonicum | R. smirnowii (Fig. 15) |

| R. fargesii | R. kaempferi | R. sutchuenense |

| R. indicum | R. orbiculare | R. williamsianum |

| R. japonicum | R. schlippenbachii | R. yedoense poukhanense |

Today there are over 300 species, varieties and clones of the genus

Rhododendron

growing in the collections and nurseries of the Arboretum, and this does not include many unnamed seedlings and over 70 clones of

Rhododendron fortunei

alone.

Ernest Henry Wilson was responsible for first bringing a collection of 50 Kurume Azaleas to the Arnold Arboretum in 1919, although a few had been introduced two years previously. It was known that these would not all prove hardy out of doors, so John S. Ames of North Easton, Massachusetts, took the collection for growing in his greenhouses, where they thrived for many years. Since that time Kurumes have become very popular and have been widely distributed throughout the South.

During these same years, some interest was being shown in the evergreen Rhododendrons and their comparative hardiness. Of course, Rhododendrons were grown in the Arnold Arboretum as early as 1890 and the collection as it is known today was growing well by 1911, at the latest. In 1916 Wilson published what he considered to be the "dozen iron-clads" for planting in New England gardens. They were:

| 'Album Elegans' | 'Charles Dickens' | 'Mrs. Charles S. Sargent' |

| 'Album Grandiflorum' | 'Everestianum' | 'Purpureum Elegans' |

| 'Astrosanguineum' | 'Henrietta Sargent' | 'Roseum Elegans' |

| catawbiense album | 'Lady Armstrong' |

|

|

Fig. 16.

R. roseum

growing in the Arnold Arboretum

Arnold Arboretum photo |

Of course to be included with these were

Rhododendron carolinianum

,

catawbiense

,

maximum

and

smirnowii.

Since that time, many more varieties and species have been added to the collections, but when the hardiness of these new ones is studied, it is a matter of comparing them with the hardiness of the "old reliables" which were recommended by Wilson in 1916 and tested for many years prior to that time by the Arnold Arboretum and by Mr. H. H. Hunnewell of Wellesley, Massachusetts.

The introduction of many of these rhododendrons and azaleas, the publication of the "Monograph of Azaleas" by Wilson and Rehder, as well as many other articles on the subject by these two staff members and others, the more modern studies currently being made on hardiness and flower color comparisons-these are a few of the Arboretum's contributions to our knowledge of this most valuable genus.

Publications

Publications of the Arboretum are of interest to the amateur gardener, and the scientifically trained botanist, as well. "Arnoldia" is a popular periodical, appearing about twelve times a year and containing many interesting notes and studies of the thousands of ornamental woody plants growing in the Arboretum.

The more technical periodicals would include the "Journal of the Arnold Arboretum," published quarterly, with botanical studies of many plant genera, and "Sargentia," issued at irregular intervals, which is also a series of contributions to our knowledge of the woody plants of the world. These publications are of particular interest to the trained botanist.

Hundreds of articles and many books have been written by Arboretum staff members on the subject of trees and shrubs. Just a listing of these would cover many pages of small type - too many to mention here. An actual count shows that each year for the past 25 years Arboretum staff members have contributed an average of 79 articles totaling 1000 pages to the various horticultural and botanical publications of the world.

Case Estates

The Case Estates of the Arnold Arboretum constitute approximately 100 acres of farm land and wooded areas, given in several gifts and bequests to the Arnold Arboretum from 1944 to 1946 by the Misses Marian R. and Louisa V. Case of Weston, together with nearly a million dollars for the general purposes of the Arnold Arboretum. The Case sisters were both very interested in horticulture, and these generous bequests have made it possible to modify somewhat the general policies of the Arboretum during the past few years. Now, most of the nurseries of the Arboretum are located on this land at Weston. Also, many plants of only minor importance horticulturally, have been removed from Jamaica Plain to the Case Estates for growing permanently. This makes it possible to relieve the crowded plantings in the Arboretum proper and to give considerably more room to the better plants remaining. The plants removed to the Case Estates are grown in long, mechanically-cultivated nursery rows and can be seen and studied at all times by any who wish to do so.

Experimental Horticulture

The facilities of the Arboretum also offer unique opportunities in experimental horticulture, for most state or federal experiment stations place far more emphasis on studies of "economic" plants (i.e., fruits and vegetables) rather than on strictly "ornamental" plants. On the Case Estates there is sufficient space to grow hundreds of azalea seedlings to test their hardiness and from which to select the better flower colors. Whenever new materials become available, whether mulches, fertilizers or weed killers, it is here that they are tried first, before jeopardizing the valued plants in permanent plantings at the Arboretum. Pruning experiments conducted here have already pointed the way to more intelligent maintenance of rhododendrons wherever they are grown, and tests are under way to provide more knowledge concerning the flowering habits of wisterias, the production of fruits by dioecious plants and the attempted regulation of flower, fruit and foliage colors of certain ornamental woody plants.

Photographs, color records, notes on important ornamental characteristics are continually being obtained and published from time to time, materially augmenting our knowledge of woody ornamentals as they are being grown in America today. All such in formation is readily available (and frequently very much in demand) to the millions of property owners throughout the country.

Plant Propagation

An extremely important phase of the work at the Arnold Arboretum has been the propagation of these woody plants. Some unknown species must be tried by several methods in order to learn the best way to propagate them. Much information has been disseminated by the Arboretum on this subject in the past, especially with regard to those trees and shrubs which are new or difficult to reproduce.

A new greenhouse-head house building is being erected now, for occupancy in 1962, which includes the latest and best greenhouse equipment. Also included is a uniquely constructed (and insulated) pit house for plant storage over winter, in which it is hoped to keep an even temperature of just a few degrees above freezing for six months of the year. The information that has been accumulated here over the years in plant propagation, plus the latest modern equipment built into these propagation units, should go a long way toward opening the door to new and better ways of increasing plants.

The Arnold Arboretum, then, famous among garden lovers for its yearlong beauty, is no less well known among horticulturists for its many plant introductions, among nurserymen for its advances in plant propagation and among botanists for its publications, its outstanding library and herbarium and its superb living collections. Its staff today carries on the traditions and endeavors to maintain the high standards set for them by the founders of this world-famous institution.