Rhododendrons at the University of California Botanical Garden - 1972

Hadley Osborn, El Cerrito, California

In General

The University of California Botanical Garden figured prominently in the early literature of the ARS, starting with Jack Whitehead's article in the first yearbook of 1945. The history of the Rhododendron Dell has not yet really been written but should be. Along the paths, among the plants, lurk a number of unusual ghosts and old dreams.

Without a doubt the most influential man in the history of the Dell was the late Dr. E. G. Vandevere. Both in terms of the plants he donated and the people he influenced. His legacy to the rhododendron world has been one of remarkably enduring quality, but his full story has not been told.

|

|

|

FIG.3.

R. spinuliferum

: an unusual

rhododendron species from Yunnan with flowers like firecrackers. Becomes a thin shrub to 8 feet. Each flower is about 1 inch long. From 6 to 8,000 feet elevation. Photo by P.H. Brydon |

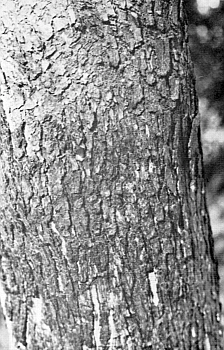

FIG. 2. The trunk of

R. diaprepes

,

UCBG. |

The ARS's earliest Quarterly Bulletins also frequently featured Jock Brydon's pictures and stories about UCBG plants. Just 24 years before this issue in Volume II, No. 1 the featured picture was the UCBG's

R. grande

, and their

R. spinuliferum

was figured later in the year. Though both will be out of flower at the time of the Annual Meeting, visitors on our tour will be pleased to note that they are still going strong. In fact, you will notice that they are going very strong. Referring to published descriptions, Jock noted that

R. spinuliferum

had an ultimate height of 8 feet, but the plant is of course making a liar out of him. In a strange but generally peaceful coexistence of strange plants, the

R. spinuliferum

is somewhat deeply over-shaded by a fine

Pterocarva stenoptera

, and is perhaps stretching upward more than it would otherwise but still manages to retain a graceful effect. The flowers have less brick red in them than is normally seen and in its best years this carries as a sheet of almost pure orange, making it a unique and valued form.

As for the

R. grande

, it and its brothers have made a forest of giants and finally a few years ago a wise worker did some needed thinning. The previous blind sides are thus currently in an awkward age of rejuvenescence, but will soon happily grow to solid splendor. The original landscape plan has worked very well, but if a number of vigorous seedlings are planted there is simply no way to space them adequately in terms of their mature size lest they get lost in the meantime (or even die of loneliness).

With the bulk of the plantings made in 1932, it is clear that in ten years a major spacing and thinning would be needed. But 1942 brought World War II, and with personnel and budget lost the work was not done. It was but one of many budgetary binds and personnel crises that such institutions are always heir to, but dedicated UCBG workers remain a little touchy about the crowded, drawn appearance of some of the plants. In my eyes it becomes a strength: Not due to the overcrowding and subsequent dieback which must constantly be fought, but for the occasional superb trunk which has emerged. On the generally sloping ground eye-level trusses are almost always available and repeated visits confirm that rhododendron trunks are almost the best part of them. From the peeling Manzanita-like mahogany of

R. stenaulum

to the split, broad-textured

R. decorum

(which a writer elsewhere remarked was almost diagnostic), to the fine-grained strength of

R. vernicosum

or

R. diaprepes

(which otherwise almost merge visually with

R. decorum

), to the smooth, mixed beige of an occasional old Thomsonii hybrid, to the almost Elm-like thrust of an

R. arboreum

, the trunks do stand with unique elegance.

As an English visitor to the 1961 International Conference later remarked, mature plants are rare in America. Even semi-mature plants of rhododendron species are particularly rare in California, and the UCBG is our major reservoir. Nonetheless, this morning while checking the Botanical Garden for the bud set that will produce the blooms you'll see, there was added evidence that the Dell is not just a dwindling museum of stubborn survivors. In addition to fresh beds housing newly introduced Malesian rhododendrons, a new raised area held young starts of some recent outstanding California hybrids.

|

|

FIG. 7 Maddenii Subseries, showing the

typical "nest" buds. |

Karl Andries

The original backbone of the rhododendron collection derives from seeds planted by Karl Andries in the mid to late 1920's. Andries did the bulk of his planting from the 1924 to 1926 expeditions, acquiring much of the seed second hand from the USDA which had in turn received it from weary sponsors inundated by the avalanche that resulted in those halcyon days when Forrest, Rock and KingdonWard were all in the field. Andries disappears from view in the early 1930's, having seen very few of his seedlings bloom.

Thanks to one of Andries' successors (Jock Brydon) his data was carefully transcribed and preserved, and examination of this record reveals a seedling raising project of colossal proportions for those pre-plastic bag and/or mist system days when raising rhododendrons from seed was not such casual work. The Andries numbers reach over a thousand in short order, and in many instances quantities were raised. Only the barest fraction of all this effort remains - but what a superb legacy it is! For us now there are flowering size plants of such as

R. protistum

(Forrest 24775),

R. facetum

(Forrest 24739),

R. delavayi

(in variety and with data), the superbly foliaged

R. sinogrande

(with one particularly well budded for your 1972 Convention pleasure), etc., etc.

The Plants

The character, problems, and resources of the Botanical Garden's Rhododendron Dell are best illustrated by talking about a few specific plants:

'Ivery's Scarlet'?...the best of the older hybrids in the Dell derive from plants imported with personal funds by Jock Brydon and a friend. One of these imported from the scrupulous Veitch Nursery came as 'Ivery's Scarlet' and has always been so labeled. It is close to but is not the 'Ivery's Scarlet' of the trade. All the old nurserymen's named introductions were clones and every 'Ivery's Scarlet' should be identical. But as fine as the plant of commerce is for California gardens, the UCBG plant appears even better, with its larger, more richly colored and more deeply spotted flowers and with larger and deeper green leaves. It is just to the north of the pond and frames it. Marvelously and unfailingly prolific, it creates a miraculous picture in mid-March.

|

| FIG. 4. 'R. lukiangense' hybrid |

'R. lukiangense hybrid'?...just after the press date for this issue, a neat, smallish plant on the China hill will be in full bloom, as it always is in late January. Were it to bloom in midseason the slight rose flowers would not be much thought of despite the fact that they cover the plant. But in January it provides valued glowing color. Though long labeled as

R. lukiangense

ssp.

admirabile

, a check a couple of years ago revealed that the plant was disqualified as that species in several important respects. Material was thus sent to Mr. Davidian at Edinburgh who kindly looked it over and confirmed that the plant could not be considered as

R. lukiangense

ssp.

admirabile

but might well be a

lukiangense

hybrid.

The Botanical Garden has graciously and patiently provided me with access to their old records and this plant is first recorded there as received in 1932 "from Washington" as

R. cerochitum

. In almost all details it matches the description of this species nicely but the leaves are not glabrescent, but retain a permanent (if very thin) coating of hairs. Still: A nagging hunch persists that identical herbarium material might well be found in the

R. cerochitum

area.

In the meantime, through an excellent cooperative relationship between the UCBG and the California Chapter's Plant Acquisition Committee, the plant has been propagated and distributed as "Lukiangense hybrid". Even though it is generally undistinguished except for its blooming period, this is clearly a case where a clonal name might wisely be provided to avoid increasing confusion. The original plant is now just 6 feet tall at forty years but propagations are proving much more vigorous and please by budding precociously and regularly.

|

| FIG. 5. R. protistum Forrest 24775 |

R. protistum

Forrest 24775: These monsters of the Grande Series are perhaps the most famous of the Botanical Garden plants. Having been awarded years ago by the California Horticultural Society, extensive local literature exists. They are part of the Andries heritage and there is no doubt about their identity or origin. Forrests' note reads:

"Shrub or tree of 30-40 ft. In immature fruit. In mixed and rhododendron forests on the western flank of the Chim-li N'Maikha - Salwin divide. Lat 26°23'N., Long. 98°48'E., Alt. 11,000 ft. August 1924. Note: The type, I think, showing an extended range southwards, GF."

In addition, Forrest at. that time marked introductions he felt had special merit with an 'X' as being good, and very special ones with an 'XX' as being very good. This received his XX. The fairly southerly- collecting point bodes ill for their hardiness. The coldest they have ever had to endure at UCBG was 18°F., and that was but a one-night stand.

Though far from the best foliage plant in the Grande Series, the flowers and fullest trusses are simply immense. Put thirty better than four inch flowers into a three-tiered creation and you take up a lot of space. Like most very early blooming things the color varies perceptibly from year to year but in the best years is much more appealing than it sounds. They open mauve, age quickly to glowing off-rose and finally fade to reveal the persistent cream underlay that contributed earlier to the unusual tones. The conspicuous and heavily-laden nectaries are royal purple.

The first account of these plants stated that they bloomed in mid-March and this has been always repeated. During the six years of our acquaintance they have always had a truss or two open at the end of January and have been at their peak in mid-February. Perhaps the last six years were all early ones. The flowers have great lasting quality and by 1971 put up with several nights of a degree or two of frost along with a hail storm without being greatly damaged.

The five remaining plants are in a row along an old terrace just above Strawberry Creek. Pinched in the same row is an

R. arboreum

x

calophytum

that no one has seen flower and what surprisingly turns out to have come from Joseph Gable in 1935. Doubtless it was sent out with a few other promising young things that had little hope of survival in Stewartstown, Pa. The bottom

R. protistum

regularly produces the fullest trusses. Repeated attempts have been made to self the bottom plant but like so many of the larger, communal rhododendrons it turns out to be self sterile. A few years ago pollen from one of the upper plants was applied to this bottom one and some seed ripened with the resulting still young seedlings appearing true. The Botanical Garden attempted a repeat of this last year on a more massive scale for the Seed Exchange, but other factors conspired so that no seed was produced. Hopefully a continuing attempt will be made.

A deceased, past employee of UCBG had an unfortunate theory that the best way to self pollinate a rhododendron was to add a heavy top dressing of pollen from another one which would presumably push the plants own previously applied pollen down the style. This appalling notion apparently was also in favor elsewhere at that time.

R. grande

pollen was used, with the result that a large number of protistum x grande hybrids are being grown as

R. protistum

. Some have come of age and the best combine the better foliage texture of

R. grande

with the larger and showier funnel-campanulate flowers of

R. protistum

. Most are blooming out creamy white. None that I've seen are true

R. protistum

.

|

|

Fig. 6. The Dell Today . . . An oak

trunk rises from the confluence of R. sinogrande and R. protistum in front of a dark jungle of R. maddenii and R. delavayi. |

There is no sense in pretending that the future of the original plants is automatically serene. Whitehead in his 1945 article mentions that the soil at UCBG was "of rather tenacious heavy clay." This is the understatement of the century. Instant war could be started between all past and present UCBG employees, since all made Herculean efforts at soil amendment but none believe that their predecessors and/or successors did enough. The soil is one of those greasy adobes that can swallow up heroic quantities of sand and humus and leave not a trace behind. Root balls thus tend to remain restricted to the areas of "made" soil and even huge plants are in effect container grown. An attempt to move one of the R. protistum back to its Golden Gate Park birthplace failed due to the very small size of the rootball in relation to top growth. Certainly the plants are currently vigorous. In fact they have in part outgrown the live oak ( Quercus agrifolia ) that previously shaded them, and an unusual hot spell last fall produced severe burning. Then, their lower branches are subject to vandalism. In the dark light of February the luminescent globes prove irresistible. Three years ago they were particularly fine and I stole six visits up the canyon. Each time several new branches and trusses had been broken off. They remain nonetheless one of the rewards of life in the Bay area.

Finally

The Rhododendron Dell is of course but a small part of the Botanical Garden and we hope to allow you enough free time to explore other areas of interest. In addition, little mention has intentionally been made of plants normally in bloom in late April. You can see them on your visit. Much of the pleasure is in the surprise of personal discovery, and our guides will attempt not to commit informational overkill.

In the meantime I'd like to thank UCBG personnel for putting up with this enthusiast. It was in the Dell that I first learned what rhododendrons were, and it was through the accident and blessing of an enduring friendship that I became interested in the plants. Though the problems are large, the Dell will always personally be a place of particular happiness.