With Camera, White Umbrella, and Tin Pants

In R. occidentale Heartland

Frank Mossman, Vancouver, Wash.

For the past seven years, Britt Smith and I have been doing field studies of

R. occidentale

. Britt is an engineer living in Kent, Washington and I am a physician in Vancouver, Washington. We bring inquiring minds to the subject though neither of us makes claim to any status as professional botanists. Britt lives 160 miles to the north of Vancouver, so that every trip to our favorite hunting area in Humboldt County, California, means over 1,000 miles travel for him. We drive by truck to the fresh water lagoon region south of Orick, thence by trail motorcycle to the back regions of one vast hillside where the real work and fun begins. We search for varieties of this species that may be unusual in some way, perhaps for hybridizing or to be grown domestically for their own beauty. Our headquarters, home away from home, is Crescent City, California, where we have lived over 3½ months during these seven years. We have seen this marvelous azalea species in southwestern Oregon from Reedsport and Roseburg on the north extending into California where it grows from the coast into the high Sierra-Nevada country, and as far south as San Diego.

On a winter night at home in our comfortable city, reading about species, one is tempted to think of each species as a fixed entity, all members alike and unchanging. Field study of

R. occidentale

indicates to the contrary. No two plants of this fascinating species are alike. For example, one prominent but variable feature is the yellow-colored upper petal. This color may vary from pale to deep butter-yellow to orange. The distribution on the upper petal may vary from dots to stripes partially covering a background of white or pink, to a solid yellow entirely covering the petal. The yellow is often seen on the adjacent upper wing petals. Only one clone has been found with a splash of this golden yellow on every petal of every floret during the seven years we have observed the plant near Crescent City, California. Plants grown from cuttings of this clone (SM30) perform similarly in domestic situations. Some hybrids of this clone demonstrate a similar color splash on all petals. The yellow is absent from some clones of

R. occidentale

.

The variations are as numerous as the number of bushes, and involve every portion of the plant. Elevations over 6,000 feet are tolerated in the Sierra -Nevada Mountains of California where the growing season is short and the winters are very cold. Desert-like conditions are no barrier to

R. occidentale

, which is found there along streams or springs as in the O'Brien, Oregon area. Only disconnected island populations are found throughout the areas of its distribution.

The most interesting variations occur along the coast of northern California in Humboldt and Del Norte counties not over a mile or two from the Pacific Ocean. Here the growing season is 328 days and though the annual average rainfall is 37-1/2 inches, the humidity is high because of the persistent fogs during the otherwise precipitation-free summer months. The average January temperature of 47 degrees is only a little below the average July temperature of 56 degrees. The rich granular acid soil is loose, giving little resistance to the water seeking roots of

R. occidentale

. These conditions are apparently nearly ideal for this species. Even there the distribution is in island groups along streams or low flat areas, or fog-bound hillsides where at least a trickle of water is present. In these coastal variation centers is a vast amount of beauty. Two blooming seasons are often seen there, one in January-February and again May through July. Bushes in prime bloom may be seen in August-September. We have been there during every month and always see some flowers.

Envision a hillside (Stagecoach Hill) several miles long, a few hundred feet high, and one or two miles wide, with many thousands of these shrubs, each one different in some way from all the others. The ideal conditions have made possible this vast collection, the large number of plants and the great variations. Every possible genetic combination is encouraged to live and thrive. Here is such a profusion of plants that the roots of one are so closely mixed with the roots of others that layers are often not taken for the sake of accuracy. Dwarf forms nestle down between taller bushes only to be found by careful investigation at an optimum moment. For example, one sixteenth inch high shrub with small, recurved, speckled, plum-colored leaves and white flowers with red picotee was seen in bloom the first time four years ago due to the careful efforts of Britt Smith, but because of annual changes in weather and blooming time, this exotic find would have gone unnoticed on subsequent years. Thus repetitious visits each blooming season are needed to make the study complete. The efforts of man have made our job of examining every plant much easier. In the past the local farmers burned this area periodically to clear the brush for pasture. This practice has been discontinued, and the competing salal, Ceanothus, redwood, sitka spruce and brambles, are rapidly returning. Soon the area will be nearly impenetrable jungle as some portions are now. The plants are presently of a height to facilitate examination. Elsewhere we have seen groves so tall that their flowers were difficult to observe. The peak of bloom is on May 30th, but tight flower buds and spent flowers are seen on adjacent shrubs then. Thus innate genetic factors are at work.

|

|

|||

|

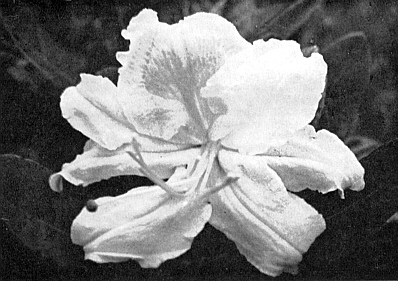

R. occidentale

'Stagecoach Frills'

Frank Mossman Photo |

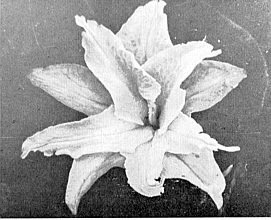

Some bushes bloom very early before the leaves appear. The later flowers come along with the leaves and new growth. The next flower buds are produced very soon after the current bloom. During this year's flower season there was an unusual amount of sunshine, so that some bushes selected for observation four years ago in prime bloom during mid-August were blooming this year on the July 4th trip. Flowers that will perhaps be useful in domestic gardens are sought; unusual colors (e.g. the deep wine-red picotee shown in color last year in ARS Bulletin Vol. 25 No. 4) ; size catches our eye, very large or small flowers. We have two clones with flowers up to four inches in diameter and one clone whereon the flowers are but 3/8 of an inch across. Flowers with thick petals, i.e., heavy substance are prized. Broad petaled and highly-frilled flowers have been catalogued. Six clones were added to our collection this year. The first was a bush with up to 54 flowers in one bud. Most species books describe

R. occidentale

with 6 to 12 flowers per truss. We have never seen as few as six per truss and have observed 25 to 35 flowers per truss, coming from a single flower bud. Other anatomical varieties are under continuing observation. The usual flower has five petals forming a star-like floret (See figure 80). We often see six or more petals on an occasional floret. This feature seems to vary on some bushes from year to year. Several clones have been collected on which all the flowers have extra petals every year without a decrease of the filaments. (Figure 81). This year we found two more petaloid doubles (i.e. the filaments were more or less changed to petals on all florets.) (Figure 82). Six years ago we found our first complete petaloid double, SM28 (Figure 83). The filaments and anthers have been entirely converted to petals, the resulting petals being all quite similar. Many hybrids of this plant have been produced. One

R. occidentale

variety, dubbed "Siamese," has eight to ten ribbon-like petals with a similar increase in filaments and often two pistils. Another clone (SM225) found by an Oregon logger who asked that his name be withheld, has 12 to 15 ribbon-like petals. SM308 has an amazing number of distorted ribbon petals and several extra pistils. SM "freak" (figure 84) has very distorted flowers. The flower buds, leaves, and wood of all these forms are normal-appearing. There is no clumping of stems as in "Witches' Broom," a problem seen on

R. macrophyllum

but not observed by us on

R. occidentale

.

|

||||

|

|

|||

| FIG. 82. Incomplete petaloid double. | FIG. 83. Complete petaloid double. | |||

Each year the observation load is increased. How is this or that plant performing? Competing shrubbery is repeatedly cleared to give the chosen shrubs a chance. Hand pollination makes a seed collection trip in November doubly necessary. We have found that

R. occidentale

will cross with many other rhododendrons or azaleas if

R. occidentale

is the seed parent, but

R. occidentale

as a pollen parent produces few seed. Knaphill azaleas have much

R. occidentals

in their background and the source of this occidentals was probably southern California where the flowers are small and white. We can't help but wonder what the results might have been if Anthony Waterer, Sr. had started with

R. occidentale

var. 'Leonard Frisbie' (SM232), as shown in color. This clone combines many desirable features: large size, broad, imbricated petals that are highly frilled, and very thick, the ultimate of

R. occidentals

beauty.

|

||||

|

Each catalogued field plant is accurately located, labeled, described and photographed. Cuttings and occasional layers are taken. Some of these plants are re-inspected several times yearly and now are studied in domestic situations as well.

The smallest flowered

R. occidentale

we have seen has been called variety 'Miniskirt' (SM157) (figure 85). It grows among other small flowered bushes near O'Brien, Oregon. The corolla is 3/8 of an inch and white. The pistil is red and normal size, contrasting 'nicely. The filaments are very short and the anthers are small, almost vestigial in the throat of the floret; this clone is worth growing for its own beauty. The leaves and the wood caliber are also small. When shown to a colleague, knowledgeable on rhododendron species, his comment was: "Well, of one thing I am certain, it is not

R. occidentals

." Of course, it is, and we must keep aware that plant species, like humans, vary.

Here on our doorstep is a genetically dynamic species offering its beauty for inspection. We feel compelled to examine every one at its zenith of bloom. Some of these bushes have crowns twenty feet in diameter indicating great age even though the canes are relatively young. This persistent hardy shrub seems capable of waiting interminable periods for the surrounding competition to fall or burn down. When conditions are right, it blooms and produces seed. The above-ground plant may die back, but the crown lives on to produce new and vigorous canes.

For some interesting field trips, check the species in your area. Carry a pack with compass, map, whistle, food, camera and notebook to name a few items.

Wear 'tin' pants, i.e., double-thickness heavy duck, to protect the legs from brambles. Leather gloves are desirable. This year a stout tripod was also carried so that pictures of greater accuracy could be obtained. On sunny days, the white umbrella is essential for proper color in pictures by providing well-illuminated shade.

Because

R. occidentale

is a water loving plant, we hunt along streams and swampy areas. Some hillsides appear to be dry, but close inspection reveals a small stream or even springs. Our olfactory sense is always on the alert for the penetrating, sweet fragrance of

R. occidentale

, the one characteristic that seems not to change.

Cuttings are made with great care, preferably in May through July. Half ripe wood is taken with one transverse cut of a razor blade at a leaf node, about 3 or 4 inches from the tip. The stem leaves are pinched off without stripping any of the stem bark so that a few terminal leaves remain. The cuttings which are placed in a plastic bag with water in an insulated case with ice in the field, have hardened like crisp lettuce by that evening when they are soaked in benylate and dexon. Then they are inserted into the cutting mixture within portable plastic tents made of cedar flats. Continuous artificial light and 65 to 70 degrees temperature seem desirable. The cutting mixture is equal parts Canadian peat and Perlite (a sterile, man-made, sand-substitute). The cuttings must not be unnecessarily traumatized, i.e., crushed, twisted, or cut a second time. Plenty of water is essential. Fully hardened and even leafless, very late cuttings will root, but less readily. Only healthy plants with years old roots will produce the flowers as seen in the native state. Fertilizers should be used cautiously.

Hardiness of the coastal

R. occidentale

is not entirely known. Some forms do well in the Midwest where ample water and acid soil with much organic material are supplied. Information on this feature is sought from growers of our seed. Contributions to the ARS Seed Exchange will be made again this year. Future articles will show differences of buds, leaves, fall color and plant habit.