The Rhododendron Grandeur and Glory of the Garden

Frank J. Anderson

Editor of the New York Botanic Garden Newsletter

Reprinted with permission from the Garden Journal, Magazine of the New York Botanical Garden

Rhododendrons are not shy and retiring blossoms born to wither unseen and scarcely noted. They can set whole gardens, woodlands, and mountainsides ablaze with pinks, reds, and yellows, or blanket the landscape in a lush carpet of white. Even when not in bloom, their foliage, often a deep and glossy green, makes them a magnet for attention. With all that in their favor, it is a matter for amazement that the rhododendron didn't find its way into horticultural use until the early part of the Nineteenth Century. Still more remarkable is the fact that it languished virtually unnoticed for the greater part of the fifty million years since it first emerged as a member of earth's families of flora.

As far back as we can determine, rhododendrons have inhabited remote areas: primarily mountainsides with difficult terrain, or the shaded jungle regions of southeast Asia and New Guinea. Obviously, such locales were not conducive to making the plant a rival of the rose in popularity. Although their range is wide, rhododendrons are indigenous to the circumpolar area, Alaska, Western North America; the Appalachians, and the Atlantic coast; plus Mediterranean Europe, the Alps, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, the Himalayas, China, and southeast Asia to Australia. Not many genera equal that kind of world-wide travel.

Despite its seeming ability to be almost omnipresent, the rhododendron seeks out very similar climatic conditions wherever it goes. The common denominator, whether it be Oregon or Malaya, is a generally temperate zone with ample moisture. As can be seen from their native habitats, rhododendrons apparently flourish best in hilly or mountainous country. They also do best in an acid soil, which is a fortunate circumstance, for acid soils are, by and large, more prevalent on the earth's surface than alkaline ones.

The genus Rhododendron is sizable, composed of somewhere between 500 and 1000 species. Probably the figure will settle at around 600 after duplications have been sorted out. This places it among the elite of plants - well befitting this aristocrat of the garden - for it is one of thirty - odd genera to include that many species. Large as the species number may be, it pales into insignificance beside the varieties that exist. There are about 10,000 of them, and new ones are coming along every day.

For a group of shrubs that was of relatively minor horticultural importance in the early 1800's, the rhododendrons have come a long way. In using the diminutive word "shrub" as a general term for this plant, it is perhaps necessary to add a word of caution; some rhododendrons can reach a height of eighty feet - not exactly a shrub like stature.

Early references to rhododendrons, in classical times, and much pre-Linnean literature, do not relate to the plant that is known by that name today. Instead they refer to the highly poisonous oleander, or Nerium. This is, unfortunately, an association not based on genetic lines - for the oleander belongs to the Apocynaceae (dogbane family), while rhododendron is a member of the Ericaceae (heaths) - but rather on the toxicity of some rhododendron species. Rhododendron luteum, the Pontic rhododendron, so called from its place of origin, Pontus (modern Turkey), is probably the most notorious of the floral Medicis. Its beautiful flowers conceal a venomous substance with an appropriately horrible name - acetylandromedol. This would he of little consequence to humans except for the fact that bees, extracting nectar from R. luteum, inevitably taint their honey with its poisonous properties.

R. hirsutum

was the first rhododendron species to make its way from the wild into a garden, an event which, according to William Aiton's Hortus Kewensis, occurred in 1656. From then until about 1800 only a dozen species came into horticultural use, and they were to he found mainly in the botanical gardens of that day. In 1775, when the Edinburgh Botanical Garden was at Leith Walk, only three species were in cultivation:

Rhododendron ferrugineum

from the European Alps, and two North American species,

R. maximum

and

R. viscosum

. Interest in rhododendrons began to grow as British and Scottish gardeners became acquainted with the virtues and the cultural needs of the genus. Exploration for ornamental plants was on the increase, and the farther reaches of Asia now began to yield the floral treasures they had guarded for eons. Between 1800 and 1899 some fifty-seven species came out of India, China, and Japan to grace English and Scottish gardens, and Britain soon assumed the leading position in rhododendron culture that it still maintains today.

Although not a single rhododendron is native to the British Isles, the climate there is eminently suited to the needs of most species. This is particularly true of the west coast of Scotland, where palm trees and subtropical vegetation thrive despite the fact that it is only about seven-and a-half degrees latitude south of Iceland. The mild, moist climate so well-loved by rhododendrons is a direct result of the warmth imparted by the Gulf Stream flowing northward to the Hebrides, Shetlands, and Orkneys.

Perhaps the finest collection of rhododendrons in all of Britain was gathered by the Duchess of Montrose at Brodick Castle on the Isle of Arran. The castle had been the home of the Dukes of Hamilton for some 250 years, during which time its interior acquired a notable series of portraits and trophies, together with splendid collections of china, silver, and wood carving. But magnificent as the interior may be, it is the gardens that provide the real show. There you can see a continuous spectacle of colors from May through August as one species of rhododendron after another breaks into bloom. The garden was the creation of the Duchess of Montrose, who fully appreciated the multitude of colors, forms, and habits of growth showered upon the genus Rhododendron. There they climb hillsides, cluster in glens, and cascade down slopes on every hand. Many of them came from Asia, brought to this bit of Scotland from the Himalayas, Malaysia, China, and the East Indies; but some from America are to be found there as well.

A tour of these gardens makes you overwhelmingly aware of the incredible variety possible from a rhododendron planting, and makes you wonder why such beauty was so long neglected. Part of that neglect was the result of the difficulty in finding species suitable for horticulture, which would survive the long, hazardous journey from their native habitats to the gardens of civilization. Merely getting specimens into cultivation was somewhat of a feat in itself. The legend grew that the rhododendron is a wealthy man's privilege because of the expense incurred in importing and maintaining the plants, especially if they were raised in quantity on a large estate.

It is hardly accidental that most of the early rhododendron breeders were, if not rich, at least men of substance. Dean William Herbert of Spofforth, Yorkshire, a son of the Earl of Caernarvon, was among the first to hybridize rhododendrons for more attractive and hardier varieties. He crossed

Rhododendron maximum

with

R. viscosum

in 1817 to produce R. 'Hybridum', a variety still being supplied by the Methuen Nurseries of Edinburgh as late as 1917. The Dean undoubtedly encouraged other hybridizing on his father's estate for it was there that J. R. Gowen crossed

R. catawbiense

with

R. arboreum

in 1813 to produce a variety that he named 'Altaclarense,' Latin for the estate's name, Highclere.

Even earlier, in 1810, Michael Waterer married the hardiness of

Rhododendron catawbiense

, only a year after its introduction into England, to another large-flowered American species,

R. maximum

. Breeding, cross-breeding, and back-breeding continued from that time on at a dizzying pace until, today, there are rhododendrons available in a color, size, and degree of tolerance to soil and temperature to suit almost every gardener's need.

Many of the early cultivated rhododendrons lacked the hardiness, ease of culture, and showy bloom that we take for granted nowadays. It is only because such nurserymen as Philip Miller, Peter Collinson, and Conrad Loddiges made American, European, and some Asiatic species available that rhododendron culture got under way, and was added to the horticultural repertoire of the gardener and the landscape designer.

With the influx, in the Nineteenth Century, of seeds from the Himalayas, China, and eastern Asia, the options at the breeder's disposal were increased tremendously, and it soon became evident that there were many more and better kinds of rhododendrons blooming in the wild and lonely places of the earth than anyone had thought possible. Plant explorers began consciously to seek them out, and the adventurous tales they told of their discoveries would easily surpass many fictional bits of derring-do.

|

This George Richmond portrait of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker shows the young man shortly after he returned from his explorations, 1847-51, in India, Sikkim, Nepal, and Tibet. A far cry from today's ten day package tours, but think of his adventures and how much he discovered!

|

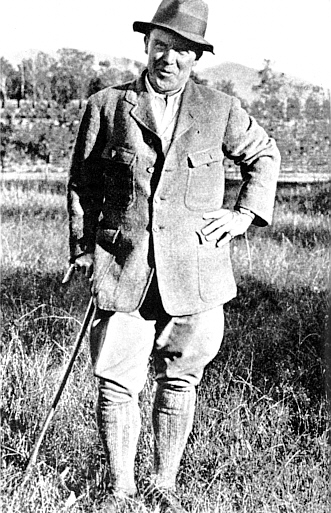

George Forrest, though exploring only in the Twentieth Century, still managed to find more than a hundred new species of rhododendron. Some he discovered, can today be seen in bloom in the great collection at Brodick Castle, Isle of Arran, Scotland.

|

Reginald Farrer, whose writings and explorations are world-famous, died while seeking new plants in Upper Burma, and asked to be buried there. Since 1920, his mountainside grave has overlooked the village of Nyitadi from 11,000 ft, Farrer's favorite altitude.

|

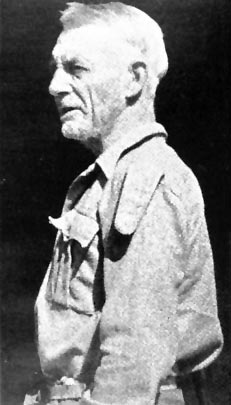

Frank Kingdon-Ward is probably the most famous of this century's plant hunters, and one of the last to move about freely in the now troubled areas of Asia. He spent most of his life in the wilds, and the last of his twenty-two expeditions ended in 1957, just a year before he died in London.

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, in search of rhododendrons in the Himalayas, was imprisoned by the Rajah of Sikkim, but managed, nonetheless, to return to England with forty-five hitherto unknown species. Ernest Henry "Chinese" Wilson, who almost lost his life on a rock-fall on a high mountain trail in western China, found almost fifty new rhododendrons on his first expedition.

George Forrest, another of the great plant collectors who added greatly to the list of horticultural rhododendrons, survived a massacre at a French mission-station on the border of Tibet. Constantly pursued, practically starving, he wandered through the mountains for nine days and nights before he finally reached safety. Still another plant explorer was Frank Kingdon-Ward, who collected about 100 new species of rhododendrons, remaining totally undisturbed at being caught in the midst of one of the greatest earthquakes to strike Asia in this century. Reginald Farrer and Joseph Rock are two more men who combed the Asiatic wilds for new floral beauty, and their adventures would run to encyclopedic length.

So, the next time you see a rhododendron blooming in a blaze of glory in someone's garden, give a moment's thought to the men who risked their lives to make it possible. And then, no matter how attractive they may be, don't eat the blossoms or the leaves! That is, unless you want an adventure of your own. Remember that the Pontic rhododendron,

R. luteum

, grew in the country of one of the world's most knowledgeable poisoners, Mithridates, Eupator of Pontus.