Distribution and Classification of Certain Japanese Rhododendrons

Frank Doleshy, Seattle, Washington

Where do we find wild rhododendrons? Why are they there instead of elsewhere? How did they get there, and when?

These are questions Mrs. Doleshy and I ask, since we are interested in rhododendron distribution. To get answers and do some related collecting, we have taken our seven trips across the Pacific, five of these to Japan. We have particularly tried to learn about the three Japanese rhododendron groups discussed in this account, namely:

I. The

R. metternichii alliance

.

II. The

R. brachycarpum

alliance.

III. Azaleas of the far south.

To understand the distribution of these rhododendrons, it is necessary to recognize that Japan's rich plant life is largely the result of a climate without major long-term fluctuations, but with a multitude of local variations. Evidently for 38 million years or more (i.e., from the Eocene Epoch) no geological period has been cold enough or hot enough to eradicate temperate-zone plants. No ice sheet has spread far from the mountains, and no tropical flora has invaded the north. Nevertheless, Japan's local climates are highly diverse, since the main islands extend as far north as the Vermont-Quebec boundary and as far south as Florida. These local climates, interacting with Japan's complex, mountainous land surface, produce a wide assortment of places where plants can grow.

In such a land, a rhododendron that has once become established is likely to have survived, but perhaps not in its original form. Instead, it may have responded to the local environments by developing into variants and new species found only in Japan. (See Ohwi 1965, p. 1; Maekawa 1974, p. 58.)

Japan's many rhododendrons commonly grow in rugged terrain. Therefore they can be a real test for any taxonomist who is trying to sort out the individual species - and who looks at a species as a plant group that remains

distinct from all others

over a long period of time. For example, a question may arise where two supposed species are growing within 50 or 100 miles of each other but are completely separated by lowlands with summers too hot for rhododendrons. lf the taxonomist has no firsthand knowledge of the terrain, he or she may think the two supposed species are merely extreme forms of a continuous population that extends clear across the gap, and accordingly should be treated as a single species. Yet if working in the field, this person would probably decide they should not be combined. (See Du Rietz 1930, pp. 357-90; Lawrence 1951, pp. 50-53; Cronquist 1968, pp. 29-30.)

As in any such complex situation, in any country, the various taxonomists have developed an assortment of classification systems for Japanese rhododendrons. Those for the metternichii group alone are outlined in the table just below.

| I. The R. Metternichii Alliance -- Alternative Classification Systems | ||||

| By Non-Japanese Taxonomists | By Japanese Taxonomists | |||

| Nilzelius | Royal Horticultural Society | Chamberlain | Ohwi | Yamazaki |

| 1961 | 1980 | 1982 | 1965 | 1964* |

| R. metternichii Sieb & Zucc. var. angustifolium (Mak.) Bean | R. makinoi | R. yakushimanum Nakai subsp. makinoi | R. makinoi Tagg | R. makinoi Tagg ex Nakai |

| typical | R. metternichii | R. japonicum (Blume) Schneider var. japonicum |

R. metternichii

Sieb. & Zucc

typical var. hondoense Nakai |

R. metternichii

Sieb. et Zucc subsp.

metternichii

var. hondoense Nakai var. kyomaruense Yamazaki |

| var. yakushimanum (Nakai) Ohwi | R. yakushimanum | R. yakushimanum Nakai subsp. yakushimanum | var. yakushimanum (Nakai) Ohwi |

subsp. yakushimanum (Nakai) Sugimoto

var. intermedium Sugimoto |

| R. degronianum | R. japonicum (Blume) Schneider var. pentamerum (Maximovicz) Hutchinson | var. pentamerum Maxim. | subsp. pentamerum (Maxim.) Sugimoto | |

|

* Apparently not available in time for the new data to be included in Ohwi's treatment. |

||||

Mrs. Doleshy and I are not taxonomists; instead we are students of distribution, using the taxonomists' findings as the basis for identifying, naming, and keeping track of the plants we see and the specimens we collect. Therefore when we encounter two or more differing systems, we select the one most compatible with our own observations - as I explain below in the discussion of each rhododendron group.

To develop any such system, the taxonomist must decide which plant groups (or "taxa") are distinct enough for treatment as varieties, as subspecies, or as species. Otherwise confusion may result from bringing together unlike plants or from separating ones that are essentially alike. In making these decisions, Dr. Yamazaki seems particularly realistic, and we have little trouble reconciling our own observations with his system. Therefore this is the one I use throughout the discussion of the metternichii group - despite my previous practice of, often, using widely accepted or well-known names.

Of the other systems, Ohwi's is essentially the same as Yamazaki's, illustrating the near-consensus already attained by Japanese botanists 18 years ago. The Ohwi system is found in his

Flora of Japan

, the standard English-language reference work published in 1965 by the Smithsonian Institution. Hence this system is frequently cited outside Japan, and I have used it a great deal; it would still be my choice if the somewhat more highly developed Yamazaki system were unavailable.

Among the non-Japanese systems, that of the Royal Horticultural Society is derived from the opinions of 50 years ago. Yet it is serviceable and inoffensive, therefore the British will perhaps use it as a stopgap while they make up their minds about Chamberlain's proposals, discussed below.

The Nitzelius system is based on intensive study of herbarium material and cultivated plants, plus some field work and an interesting historical review. Although Nitzelius's discussion includes many fresh insights, I do not believe his drastic consolidation of the species has been widely accepted. Greater opportunities for field work perhaps would have resulted in different conclusions.

Chamberlain, of Edinburgh, has proposed a system which includes unusual combinations; also he has proposed that the name of

R. metternichii

be discarded in favor of

R. japonicum

. The name change is widely opposed, and no further discussion seems necessary here. Yet it appears that some of the questions raised by his proposed classification are not widely known, so I do discuss them here.

In his key to the metternichii group, the first step is an attempt to separate out subsp.

yakushimanum

and

R. makinoi

or combination into one species The separation method consists of deciding whether a plant matches Statement A or B, as follows:

A. Rhachis 2-5 mm (this is the axis of the flowers, exclusive of the supporting stalk, and can be seen as a rough, woody spike after the flowers drop off); leaves 2.5-10 x as long as broad; pedicels densely fulvous-tomentose.

=

R. yakushimanum

, including "subsp.

makinoi"

B. Rhachis 10-20 mm; leaves 3-4 x as long as broad; pedicels sparsely tomentose.

= Other members of group, including "var.

pentamerum

"

Statement A, obviously, is designed to include the narrow leaves of

makinoi

, also to take in any

yakushimanum

with leaves 2.5 to 3 times as long as their own width.

When I tested this Chamberlain key on a sample of 39 dried specimens - collected in the wild and including subsp.

metternichii

varieties, subsp.

yakushimanum

, and subsp.

pentamerum

- I did

not

obtain the intended results. Most of the subsp.

pentamerum

and all the subsp.

yakushimanum

had rhachis more than 5 mm. but less than 10 mm. long, thus fitting neither Statement A nor Statement B. Actually, contrary to the key, I found the

yakushimanum

rachises averaged slightly longer than those of the

pentamerum

. Also several specimens of

pentamerum

had densely hairy pedicels, which would put them in the "wrong" group. Surprised at these results, I re-measured the rhachis, adding in the length of the non-flower-bearing tissue at the base (in my opinion, the peduncle). Yet, with these new measurements, Chamberlain's method still did not distinguish between

yakushimanum

and

pentamerum

.

In other words, when I compared real-life specimens of these two subspecies with Chamberlain's concept of

yakushimanum

, I found that neither one matched very well, but that the

pentamerum

was at least as close as the

yakushimanum

.

While this method of separation may sometimes succeed, it also, obviously, may not. Therefore it does not seem suitable as a basis for a major regrouping, i.e., making one species out of subsp.

yakushimanum

and

R. makinoi

- and I can see no other basis for this regrouping. Actually, I cannot understand why Chamberlain wishes to combine the highly distinctive

R. makinoi

with anything else. I think he would agree with his fellow worker at Edinburgh, Cullen, in saying that "species differ from their closest neighbors in at least two correlated characteristics" (Cullen 1980, p. 32). And in the case of

R. makinoi

, the correlated differences include narrow leaves, semi-bullate leaf surfaces, long-retained bud scales, tolerance of shaded, low-elevation habitats, and late appearance of new growth. Therefore I think any person with firsthand knowledge of the plant would want to keep it a separate species, as I treat it here. (Nitzelius, in his 1961 paper, discussed a plant with similar narrow leaves, found far from the known territory of

R. makinoi

. But in 1973 personal correspondence, he agreed that this plant may have been a cultivated one. Also, despite some searching just east of the known

R. makinoi

territory, we have not found anything similar to it.)

Turning to var.

hondoense

Chamberlain omits this from his key. Yet in his discussion (1982, p. 309), he recognizes the existence of a thinly indumented

R. metternichii

- which others call var.

hondoense

- and he says there are undoubtedly intermediates between this and the typical form. Despite these intermediates, he suggests that the thinly indumented form can be accepted as a variety or subspecies "if the geographical separation of the two forms is confirmed". He can probably find the requisite amount of confirmation in Yamazaki's distribution data (1964, p. 17), and I believe we should continue to recognize var.

hondoense

.

Chamberlain also does not recognize var.

kyomaruense

as a separate entity; instead he mentions it as probably "no more than a local geographical variant of var.

pentamerum

" (1982, p. 310). His evidence, apparently, is the fact that both have 5-lobed flowers, but I believe this evidence is insufficient - for reasons I give below in the "Specifics of Distribution".

Explanatory Key

The individual members of the metternichii group differ in leaf size, shape and surface texture, kind of indumentum, number of flower lobes (usually matched by the number of seed capsule sections), growth habit, and ecological preferences. Perhaps the clearest way to explain these differences is to arrange them in the form of a key (below) based on the Yamazaki classification. By also including geographical separations, this key is simplified so that the user need only consider the more obvious features of the plants. And, like any other key, this one consists of alternative choices, as follows:

1A. Plants with linear-oblanceolate leaves at least 7 times as long as their own width; lower surfaces covered with thick, beige or brown indumentum. Flowers generally 5-lobed. Erect shrubs found in a limited area of Honshu.

R. makinoi

1B. Plants with oblong-elliptic to oblanceolate leaves shorter than 7 times their own width

R. metternichii

, divided as follows:

2A. Plants of Yakushima.

3A. Indumentum thick, velvet-like or spongy, buff or brown; leaves usually of domed shape. Plant heights usually no more than 2 meters.

subsp.

yakushimanum

var.

yakushimanum

3B. Indumentum thin and light-colored; leaves more or less flat. Plant heights to 5 meters and sometimes more. Common below 1450 meters but sporadically present at higher elevations

subsp.

yakushimanum

var.

intermedium

2B. Plants other than those of Yakushima.

4A. Found northeast of Fossa Magna depression (which separates NE from SW Japan). Indumentum velvet-like to spongy, pale brown to pink-buff. Flowers generally 5-lobed. Plant heights seldom more than 2 meters.

subsp.

pentamerum

4B. Found southwest of Fossa Magna and also on Izu Peninsula, which is a south extension of Fossa Magna volcanos. Indumentum of various kinds; flowers 5-lobed or 7-lobed. Plant heights often greater than 2 meters; may exceed 3 meters.

5A. Indumentum thin and ap-pressed, usually with somewhat the sheen of a plain-woven, lustrous cloth such as taffeta, medium tan or lighter in color.

6A. Flowers generally 7-lobed.

subsp.

metternichii

var.

hondoense

6B. Flowers generally 5-lobed.

subsp.

metternichii

var.

kyomaruense

5B. Indumentum thicker, often darker, only rarely spongy. When viewed through hand lens, resembles cotton batting.

subsp.

metternichii

var.

metternichii

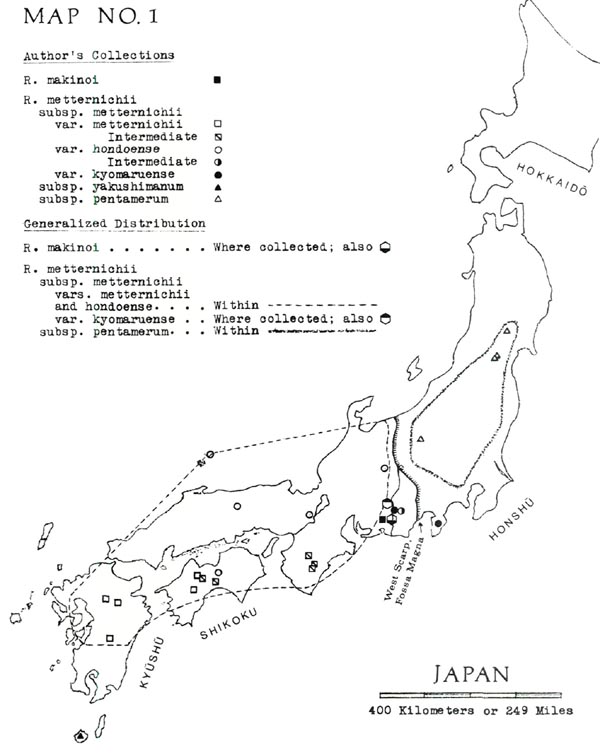

Brief English-language descriptions, omitting the new var. kyomaruense , are given by Ohwi (1965, p. 698). For specifics of distribution, see my Map No. 1, showing both our own collections and the limits of distribution.

|

Factors Influencing Distribution

Once we have a satisfactory classification system for keeping track of the plants, we can try to determine what has caused them to be in the places where now found, but not in other places. The most obvious factors are, first, the major barriers, such as waterways and lowlands, and second, the migrational pathways, such as mountain chains. Another factor with fairly obvious effects is the climate, with its local variations reflecting elevation, latitude, and exposure. Somewhat less obvious are the soil conditions, which for most rhododendrons must be porous, cool, and moist, but free from excessive water. More subtle, speculative factors are:

— Adaptability of particular species to environmental change.

— Effect of cyclic or long-term weather changes (which, as mentioned, have been moderate in Japan).

— Effect of new traits from elsewhere, entering via overlapping distributions or migrational pathways, or via movements of the earth's crust.

— Effect of new traits from mutation or from recombination of existing traits.

— Relative vigor of taxa growing in the same locality.

— Viability of hybrids.

Specifics of Distribution

Since so many factors may be involved, any attempt to explain the distribution of a particular rhododendron may seem like pure surmise. Yet some possible cause-and-effect relationships can be suggested.

More ancient rhododendrons?

Three members of the metternichii group have both 5-lobed flowers and heavy indumentum; these are subsp.

pentamerum

, subsp.

yakushimanum

, and

R. makinoi

. Although

R. makinoi

has unique traits, all three are somewhat similar in appearance. Also all three are found in more or less outlying locations, namely, northern Honshu, far-southern Yaku Island, and a geologically disjunct area of central Honshu. Hence these plants could perhaps be the surviving remnants of populations once widespread in Japan, at least along the Pacific side.

Concerning their possible ancestry, several suggestions are available, although most of these are rather vague because they relate to the entire Pontica Subsection or at least to all its Japanese members, i.e., the metternichii group plus

R. brachycarpum

and

R. aureum

. Tagg (in Stevenson 1947, pp. 20 and 568) suggests links with Subsection Argyrophylla and with southern members of Subsection Taliensia; Hutchinson (1946, p. 45) a link with Subsection Fortunea; and Chamberlain (1982, p. 305) a link with Subsection Argyrophylla.

A Taliensia relationship seems plausible for the

pentamerum-yakushimanum-makinoi

plants because of indumentum similarity. And, consulting Hedegaard's work on rhododendron fruits, seeds, seedlings, and hairs (1980), I find that his drawings and descriptions tend to confirm a link with the Taliensia species, especially

R. bureavii

. On the other hand, Spethmann (1980a and 1980b) presents biochemical and other data indicating that the Taliensia and Pontica Subsections are far apart. Therefore the possible link between these two subsections must be considered flimsy until we have better evidence, such as fossils. Also the distinctive features of

R. makinoi

may indicate separate ancestry.

Aside from some biochemical similarity found by Spethmann, I see little to support Hutchinson's idea of a Pontica-Fortunea link. On the other hand, Tagg's and Chamberlain's Argyrophylla link - also suggested by K. Wada (see ref.) - is fairly well supported by flowers, foliage, and plant habit. Yet this link seems pertinent not to

pentamerum-yakushimanum-makinoi

but rather to the other metternichiis, discussed in the following sections.

|

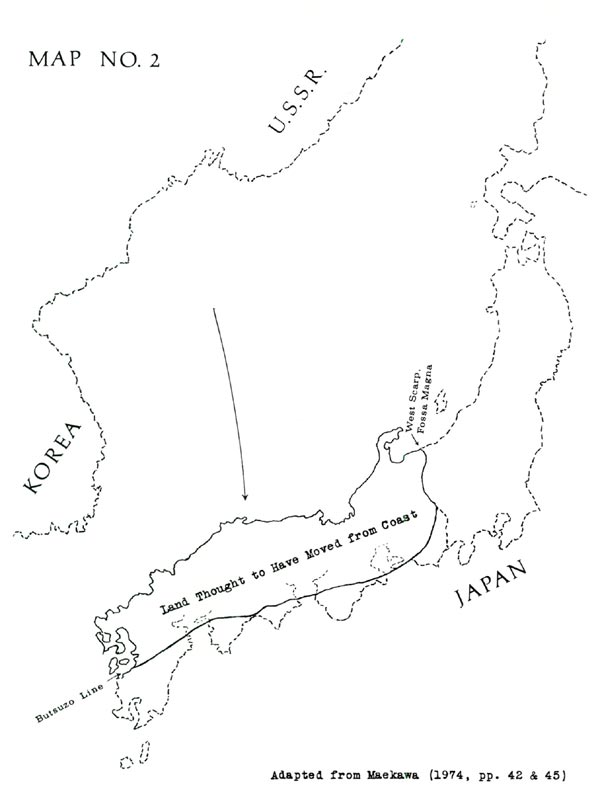

The present wide dispersion of pentamerum-yakushimanum-makinoi is perhaps best explained by a recent hypothesis: that most of southwestern Japan is actually a piece of land which departed from the Asian coast and moved to the position of Japan, as shown in Map No. 2. Making this hypothesis credible, the piece in question would fit neatly into the Korean-Siberian coastline; also its geological formations match those of Korea and Siberia (filling a distinct gap) but do not match those of the adjacent Japanese territory. (See Maekawa 1974, pp. 34-58. Also Maekawa cites Horikoshi 1972.)

|

|

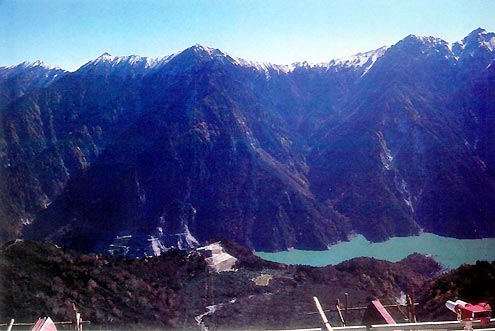

Interior view of mountain wall at east end of land

thought to have moved from mainland coast. photo by Frank Doleshy |

The move evidently occurred no earlier than 65 million years ago, possibly more recently than 26 million years ago. Therefore the pentamerum-yakushimanum-makinoi rhododendrons (or their ancestors) might well have been present in preexisting lands of Japan; and with arrival of the added land, these plants would have become the inhabitants of an outer area. In addition, some disruption of previously-existing flora would have been likely, accounting for the wide gaps in today's distribution.

Relationships between var.

hondoense

, possibly more ancient rhododendrons, and var.

metternichii

.

The ancestor of var.

hondoense

- perhaps a member of Subsection Argyrophylla - could have arrived in Japan either via continental contact or else via the newly hypothesized land movement. If by continental contact, and if the incoming rhododendron encountered others already present in Japan - such as

pentamerum-yakushimanum-makinoi

- hybridization could have occurred. This would probably have left evidence in the form of transitional plants all the way across the new plant's zone of influence, beginning at its point of entry. On the contrary, if the incoming rhododendron arrived by land movement, a more distinct break might be found in today's populations. This would be likely if the arriving species were more vigorous than any others it came to, thus able to survive without change in its own territory and also spread south into new territory beyond the line where the new land docked with the old. In this new territory, it would perhaps hybridize with already-present species.

The latter series of events seems to be approximately what happened, since we find, first, a large area of practically pure var.

hondoense

in southwestern Honshu; second, a mosaic of intermediates across the Kii Peninsula, Shikoku (and perhaps Kyushu); third, var.

metternichii

in the south, particularly in central and southern Kyushu. The more or less homogeneous var.

metternichii

, it appears, may be the product of hybridization between the incoming var.

hondoense

(or ancestor) and a pre-existent southern rhododendron resembling subsp.

yakushimanum

or

pentamerum

. Such a hybrid origin would explain the following intermediate characteristics of var.

metternichii:

— Indumentum dense although relatively thin.

— Indumentum colors varied and often vivid.

— Leaf size and shape bridging the differences between those of the supposed parents.

Actually the preexistent southern rhododendron may not have been entirely swallowed up, since a stand near the summit of Mt. Ishizuchi - the highest peak in the transition zone - is strikingly similar to subsp.

yakushimanum

, but is not very much like the var.

hondoense

around the foot of the mountain or even halfway up the mountain.

While the flowers of vars.

metternichii

and

hondoense

are generally 7-lobed, the flowers of their supposed ancestors in Subsection Argyrophylla are 5-lobed. Yet the 7-merous trait could be of fairly recent origin, as I suggest in the immediately following section on var.

kyomaruense

.

Var.

kyomaruense

as a separate entity

.

Chamberlain, in making his above-mentioned suggestion that var.

kyomaruense

is a local variant of subsp.

pentamerum

, apparently relies on the fact that both have 5-lobed flowers. This does not seem a sufficient reason for combination because:

— Var.

kyomaruense

differs from subsp.

pentamerum

(and resembles var.

hondoense

) in height, growth habit, leaf size and shape, and leaf indumentum.

— In addition, var.

kyomaruense

cannot reasonably be considered a hybrid between subsp.

pentamerum

(5-lobed) and var.

hondoense

(7-lobed), since K. Wada found that 7 lobes are dominant over 5 lobes. (See ref.)

Therefore it seems clear that we should continue to accept var.

kyomaruense

as a separate entity, allied with var.

hondoense

rather than subsp.

pentamerum

.

Differences between var.

kyomaruense

and subsp.

pentamerum

can perhaps be attributed to the fact that these two plants are on opposite sides of the Fossa Magna, which is the boundary of the piece of land thought to have moved out from the Asian coast. Var.

kyomaruense

or its ancestors may have arrived aboard this land, while subsp.

pentamerum

(as discussed above) may be one of the more ancient Japanese rhododendrons.

This leaves one major question: why do var.

kyomaruense

and var.

hondoense

, otherwise so much the same, have respectively 5-lobed and 7-lobed flowers? A possible explanation, which K. Wada and I developed in a conversation several years ago, is that both plants originally had 5-part flowers (and may indeed have been simply the same plant); that the 7-part flowers resulted from mutation or genetic recombination; that this trait turned out to be dominant and swept over nearly all the range of these varieties but did not penetrate the geographically-isolated enclaves of var.

kyomaruense

.

In support of this explanation, I can say that the var.

kyomaruense

stands are indeed isolated; they are found only on the Izu Peninsula and in the Akaishi Mountains, the latter consisting of parallel ranges deeply separated by tributaries of major rivers. Concerning the number of flower parts, a spontaneous, self-perpetuating change is believable, since in 1967 Mrs. Doleshy and I found a Kyushu

R. metternichii

population with 15%-20% 8-part flowers, and the

Journal of Japanese Botany

(1969) reported a similar find in southwestern Honshu. (Actually, Mr. Wada and I were discussing the Kyushu find when it suddenly occurred to us that we might be able to explain var.

kyomaruense

.)

Summary, distribution of

R. metternichii

and allies.

Subsp.

yakushimanum

, subsp.

pentamerum

, and

R. makinoi

appear to be the more ancient members of the metternichii group, and they may have a link with Subsection Taliensia. Yet

R. makinoi

is so distinct that its origin is probably somewhat different from that of the other two.

Vars.

hondoense

and

kyomaruense

, of subsp.

metternichii

, appear to be descended from more newly arrived ancestors, probably members of Subsection Argyrophylla. The typical subsp.

metternichii

var.

metternichii

perhaps originated from a merger of the more ancient and the newer rhododendrons, in a portion of southwestern Japan where they met.

Dry land connections have generally been considered the routes of plant migration from mainland Asia to Japan. Yet, according to a recent hypothesis, some or many of these plants could have reached Japan as passengers on a piece of land which moved out from the Asian coast and became a large part of southwestern Japan. This hypothesis provides attractive explanations for several aspects of rhododendron distribution, namely:

— Geographical dispersion of the

pentamerum-yakushimanum-makinoi

component.

— Disappearance of any similar rhododendron in southern Kii-Shikoku-Kyushu, perhaps as a result of absorption into new var.

metternichii

.

- Discontinuities in rhododendron distribution along the major geological lines found where the new land would have docked with the old. These discontinuities include:

a. Separation of vars.

hondoense

and

kyomaruense

from subsp.

pentamerum

, with the Fossa Magna between.

b. The zone of intermediates between var.

hondoense

and var.

metternichii

.

c. The var.

kyomaruense

enclaves and the

R. makinoi

enclaves. Moreover, the land-move hypothesis would explain the lack of significant discontinuities in the inner portion of the new land, i.e., the main territory of var.

hondoense

.

II. THE

R. BRACHYCARPUM

ALLIANCE

Subordinate Taxa

R. brachycarpum

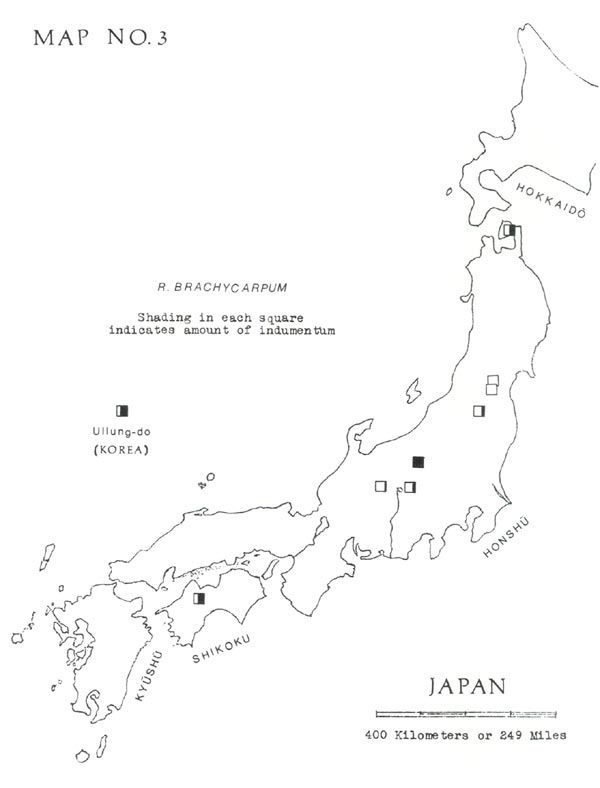

has usually been split into two species, two subspecies, or two varieties, depending on leaf indumentum. This, when present, consists of pale brown hairs in a dense layer, generally less than ½ millimeter thick. Often on a green leaf it is practically invisible to the naked eye but can be detected by gradually turning the leaf edgewise and looking for a brownish shading on the undersurface. On dried leaves it is best detected by scraping with a dull knife, under a lens. As shown in Map No. 3, the distribution of this indumentum does not seem to follow a geographical pattern.

|

I think the plants with indumentum should, at most, be considered a variety. Therefore, when I make the distinction, I use the Ohwi names (1965, p. 698), as follows:

— Without indumentum = typical

R. brachycarpum

D. Don

— With indumentum =

R. brachycarpum

var.

roseum

Koidz.

Chamberlain, apparently more impressed than Ohwi by the significance of the indumentum, considers it a basis for dividing this species into two subspecies, and he proposes a rearrangement of the names used by others (1982, p. 307).

Distribution and Ancestry

In Japan, unlike any one member of the metternichii group,

R. brachycarpum

is found on both sides of the Fossa Magna. Also it grows farther north than the metternichiis, reaching the cold central region of Hokkaido. South, it extends to Mt. Hakusan and to the two tallest mountains of Shikoku: Tsurugi and Ishizuchi (the latter being taller than any mountains farther south in Japan). In Korea, where no

R. metternichii

is found,

R. brachycarpum

extends north nearly to the Siberian boundary but apparently does not cross it; also it grows on Ullungdo, an island 85 miles toward Japan from mainland Korea. Nitzelius (1972) distinguishes the Korean plants (including those of Ullungdo) as subsp.

tigerstedtii

, on the basis of larger leaves and flowers, longer shoots, and extreme cold hardiness.

The southern limit of Japanese distribution, in Shikoku, indicates a lack of heat tolerance. Also, wherever we have seen this species in Japan (i.e., as far north as Sendai), the new growth comes earlier than the flowers. This does not seem to interfere at all with the plant's vigor, but it may indicate a place of origin farther north, where long days come earlier in the spring. A possible source, therefore, is the 12 to 26 million-year-old Miocene vegetation of northeastern Japan. According to Maekawa (1974, pp. 49-55), this vegetation included the Rhododendron genus; also she indicates the probability of a connection with the Siberian coastline, as it then existed. If the plant thus migrated from the north, it may have reached southwestern Japan before there was any such barrier as the Fossa Magna. Alternatively, instead of coming from, or via, northern Japan, it may have been a passenger on the piece of land thought to have moved out from the mainland coast, or it may have arrived via both a northern route and the added land. (Nitzelius, in personal correspondence dated January 24, 1975, said a dual route was suggested by the fact that cultivated

R. brachycarpum

in Sweden falls into two groups flowering a month apart.)

Regardless of which routes it followed, a longer pathway apparently linked it with similar western Chinese species that are centered around

R. lacteum

(Tagg in Stevenson 1947, pp. 370, 567-8, 571, 682; Cowan 1950, pp. 35, 62, 81; Davidian 1955, pp. 123-4; Nitzelius 1961, pp. 150-1; Seithe /v. Hoff 1980, p. 97). However I am not aware that any taxonomist has yet made a formal proposal that would combine

R. brachycarpum

with those species.

Also not to be ruled out is a possible link via land bridge with somewhat similar North American rhododendrons, namely,

R. maximum

,

R. catawbiense

, and

R. macrophyllum

. For interesting additional comments on worldwide distribution of Subsection Pontica, see Cox 1979, p. 14.

Hoping to find out more about the sources of Japanese

R. brachycarpum

, Mrs. Doleshy and I went to Korea in September-October, 1982, but unfortunately learned little. Therefore to do what we intended, we will perhaps go there again.

In Japan, this species is a notable pioneer. Yoshioka (1974) mentions its prompt appearance on volcanic deposits, and we have thus seen it at Zao and Yokodake. As a result of such territorial expansions it is very common, often being found with other rhododendrons. It has evidently hybridized with

R. aureum

producing

R. x nikomontanum

, and with

R. metternichii

subsp.

pentamerum

, producing

R. x hidaense

(Hara 1948, p. 126; Ohwi 1965, p. 698). Yet both hybrids seem of extremely limited occurrence, perhaps indicating they are unable to compete with their parent species.

III. AZALEAS OF THE FAR SOUTH

Writing about the antecedents of the Kurume azaleas for the October, 1974 A.R.S.

Bulletin

, I tried to sort out the native azaleas of southern Kyushu. These are:

Generally recognized species.

—

R. kiusianum

Makino, the small or spreading plant with very hairy leaves and rose purple flowers, found wild on the high peaks of Kyushu but not elsewhere.

—

R. kaempferi

Planch., upright but much branched, with less hairy leaves than

R. kiusianum

and usually brick red flowers, common from Kyushu to the north island of Hokkaido.

Less well-known species.

—

R. sataense

Nakai, almost as upright as

R. kaempferi

, with shiny, sparsely-haired leaves and varied flower colors (pink, salmon, purple, red, etc.), found on the Osumi Peninsula, at the southeast corner of Kyushu. Probably the source of most Kurume azaleas in cultivation.

Mixed or indefinite groups.

—Natural hybrids between

R. kiusianum

and

R. kaempferi

, found on Kyushu volcanoes. Plants of intermediate stature, with approximately the same flower color range as

R. sataense

but usually with more hairy leaves.

—

R. obtusum

(Lindl.) Planch., described by Ohwi (1965, p. 700) as "widely cultivated and probably of hybrid origin involving

R. kaempferi

and several other species." In contrast, E.H. Wilson used

R. obtusum

as the species name for an assemblage of plants including

R. kiusianum

,

R. kaempferi

, and their derivatives (Wilson and Rehder 1921, pp. 29-43). Moreover, some Japanese have apparently used this name for plants now called

R. sataense

(Kumazawa 1 958).

|

|

Yaku-like indumentum on a

high-elevation Shikoku rhododendron. photo by Frank Doleshy |

Here, I am confining my further comments to

R. sataense

- its origin, distribution, and status. For much of my information, I am indebted to Dr. Masaaki Kunishige, formerly at the Kurume Horticultural Research Station, now at a Honshu research station, but still working with azaleas. He considers

R. sataense

an ecological variant of

R. kaempferi

, found at higher elevations. He does not rule out possible hybrid ancestry - i.e.,

R. kaempferi

plus some contribution from

R. kiusianum

- which I think may account for the variety of flower colors. He points out, though, that

R. sataense

has a more or less upright habit of growth, as well as shiny leaves with few hairs, thus resembling

R. kaempferi

but not

R. kiusianum

.

When we went out on the back roads as Dr. Kunishige suggested, we saw that

R. sataense

grows in an unusual area where: first, it has been partially isolated from outside influence by low-lying land to the north and by volcano-caused destruction of vegetation; second, the volcanic activity has opened up areas for colonization by the more vigorous, well-adapted azaleas; and third, one portion of the available habitat is largely free from volcanic deposit, hence has probably served as a plant refuge during eruptions.

These circumstances seem largely responsible for the emergence of today's

R. sataense

. Despite the variations in flower color, it is nearly uniform in flower shape, pattern of flower blotching, plant stature, and leaf characteristics. Occurring at higher elevations than

R. kaempferi

, in its own well-defined area, it appears to remain distinct. Therefore it appears to have the stature of a species, or at least a subspecies in the process of becoming distinct.

CONCLUSION

We have tried with varying success to learn where certain rhododendrons are found and what circumstances and events brought them to these places. To do this, we have had to learn more and more about the land and its boundaries, its surface features, and its climates - both present and past. The broader parts of this knowledge come from geographers and geologists. But equally important is the local knowledge that can only be obtained by field observation and by talking with people who live there.

From taxonomists we obtain another essential kind of knowledge: how to identify, name, and group the plants. Yet we often encounter conflicting taxonomic opinions, therefore must choose the more credible alternatives. We make these choices by determining which opinions can be reconciled with our own observations, and we usually find that the taxonomists who work in their own country are the ones whose views we can adopt.

The value of field work and geographical knowledge is not a new discovery; Du Rietz (1930, p. 388) went so far as to say "a modern botanical museum-official, of course, ought not only to be allowed but even forced to spend at least several months of the year in field-study of the populations he has to deal with in his museum during the rest of the year."

Also recognizing the importance of firsthand knowledge, Hideo Suzuki (speaking for himself and friends in the Japanese Rhododendron Society) recently stated that "our conclusion on the matter is to let Japanese taxonomists classify Japanese Rhododendrons, let Taiwan taxonomists classify Taiwanese Rhododendrons and so on, and let Edinburgh people take care of the final arrangement by consulting with the respective taxonomists." I must agree.

References

Chamberlain, D.F. 1982. Revision of Rhododendron II, Subgenus Hymenanthes.

Notes from Royal Bot. Gard. Edinburgh

39: 209-486.

Cowan, J.M. 1950.

The Rhododendron leaf.

Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

Cox, P.A. 1979.

The larger species of Rhododendron.

London: Batsford.

Cronquist, A. 1968.

The evolution and classification of flowering plants.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Cullen, J. 1980. Rhododendron taxonomy and nomenclature. In

Contrib. toward a classification of Rhododendron,

ed. J.L. Luteyn and M.E. O'Brien, 27-38. New York: N.Y. Bot. Gard.

Davidian, H.H., and J.M. Cowan. 1955. Revision of the lacteum series.

Rhod. and Camellia Yr. Bk.

10: 122-55.

Doleshy, F.L. Accounts of field observations given in

Qtr. Bui. Am. Rhod. Soc.

1966. 20: 3-9, 76-86, 147-58. 1968. 22: 145-59., 1970. 24: 68-79, 147-53, 1971. 25: 31-38, 84-91, 1972. 26: 20-22, 102-4, 193-5, 1974. 28: 206-16.

Du Rietz, G.E. 1930. Fundamental units of biological taxonomy. (English)

Svensk Bot. Tid-skrift

24: 333-428.

Geological Survey of Japan. 1968 and later eds. 1:2,000,000 maps. (Japanese and English): Geological map of Japan; Volcanoes of Japan; Tectonic map of Japan. Pub. at Kawasaki by Geol. Survey of Japan.

Hara, H. 1948. Occurrence and distribution of rhododendrons in Japan.

Rhod. Yr. Bk.

3: 112-27.

Hedegaard, J. 1980.

Morphological studies in the genus Rhododendron.

2 vols. Copenhagen: G.E.C. Gads.

Horikoshi, E. 1972. Orogenic system of the Japanese Islands. (Japanese)

Kagaku

42: 665-73.

Hutchinson, J. 1946. Evolution and classification of rhododendrons.

Rhod. Yr. Bk.

1: 42-47.

Jour. Japan. Bot

1969. Materials for the distribution of vascular plants in Japan: an octomerous form of

Rhododendron metternichii.

(Japanese) 44: 159.

Kumazawa, S. 1958. Kurume Azalea. (English) Photocopy distrib. by Kurume Branch, Horticul. Research Stn., Miimachi, Kurume.

Lawrence, G.H.M. 1951.

Taxonomy of vascular plants.

New York: Macmillan.

Maekawa, F. 1974. Origin and characteristics of Japan's flora. In

The flora and vegetation of Japan

(English), ed. M. Numata, 33-86. Tokyo: Kodansha.

Nitzelius, T.G. 1961. Notes on some Japanese species of the genus Rhododendron. (English)

Acta Horti Gotoburg.

24: 135-74.

-------, 1972. Rhododendron brachycarpum ssp. tigerstedtii.

Qtr. Bui. Am. Rhod. Soc.

26: 165-8.

Ohwi, J. 1 965.

Flora of Japan.

(English) Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

Royal Hort. Soc. 1980.

Rhododendron handbook, Rhododendron species in cultivation.

London: Royal Hort. Soc.

Seithe/v. Hoff, A. 1980. Rhododendron hairs and taxonomy. In

Contrib. toward a classification of Rhododendron

, ed. J.L. Luteyn and M.E. O'Brien, 89-115. New York: N.Y. Bot. Gard.

Spethmann, W. 1980a. Flavonoids and carotenoids of rhododendron flowers. In

Contrib. toward a classification of Rhododendron

, ed. J.L. Luteyn and M.E. O'Brien, 247-75. New York: N.Y. Bot. Gard.

Spethmann, W. 1980b. Infragenerische Gliederung der Gattung Rhododendron. Doctoral diss., University of Hamburg, Germany.

Stevenson, J.B., ed. 1947.

The species of Rhododendron

. 2d ed. London: The Rhod. Soc.

Takai, F., T. Matsumoto, and R. Toriyama, eds. 1963.

Geology of Japan

(English) Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Wada, K.

The cited comments are those given the author verbally during years of friendship.

Wilson, E.H., and A. Rehder. 1921.

A monograph of azaleas

. Cambridge, Mass.: University Press. Reprinted 1977 at Little Compton, R.I., by Theophrastus.

Yamazaki, T. 1964. A new variety of

Rhododendron metternichii

and its alliance. (Japanese, English summary)

Jour. Japan. Bot.

39: 13-18.

Yoshioka, K. 1974. Volcanic vegetation. In

The flora and vegetation of Japan

(English), ed. M. Numata, 237-67. Toyko: Kodansha.