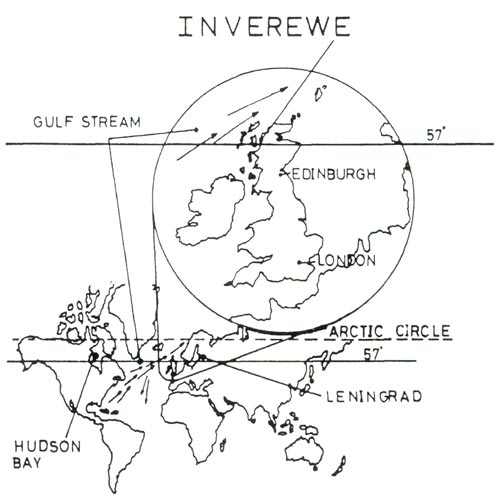

Paradise 9° Below the Arctic Circle

David R. Mitchell

Edinburgh, Scotland

Reprinted with permission Rhododendron Society of Canada Bulletin Fall 1984.

You will all know where Hudson's Bay is, but are you aware that further along the 57° parallel lies a Plantsman's Shang-ri-la - Inverewe? This garden (240 miles from Edinburgh, 644 miles from London), on the rugged west coast of Scotland, surrounded by mountains, lochs and highland glens, is a real joy to visit. Unfortunately it is probably fair to say that many of you reading this article will never have been to Inverewe, but hopefully after reading it you may be tempted to come to Scotland for a holiday and visit both Inverewe and some of our other great west coast gardens.

You may ask, if there are other gardens, why write about Inverewe? Two reasons, the first being that I was employed there for nearly two years as a propagator/gardener, and the second and more important, that it was one of the first west coast gardens to be created, with work beginning in 1865 on planting a windbreak with Scots Pine and Corsican Pine as the predominant types.

The inspiration for this work and in due course the garden came from Osgood Mackenzie, born in 1842, third son of the twelfth Laird of Gairloch. A forward-thinking man, Mackenzie, with help from his mother, bought Inverewe estate and the adjoining one of Kemsar in 1862.

The headland on which the garden now stands was at that time a barren desolate place, windswept and with nothing growing on it except Crowberry and coarse patches of Heather. The soil, if you could call it that, was and is still in many places thick acid peat, almost black in colour, varying in depth from one metre to almost nothing. The base rock underlying the peat is Torridon Red Sandstone, a hard and ancient rock laid down in the Precambrian period.

|

|

Loc Ewe near Inverewe

Photo by Barrie Porteous |

Not really the sort of place to try to create a garden, but Inverewe as a site had several things in its favour. Am Ploc Ard (The High Lump) as the headland was known, is surrounded by Loc Ewe on three sides, creating a micro-climate. A further factor affecting the garden is the Gulf Stream (see map), which arises in the Gulf of Mexico then moves eastwards across the Atlantic bringing warm air and moisture with it. This gives a high rainfall, 1,533 mm (60 inches) per annum, and mild winters; -8.4°C (+18°F.) is the lowest temperature recorded since records began in 1962.

|

The total area of the garden is 27 hectares (65 acres). The windbreak forms the boundary of the garden with its essential deer fence on the outside of it. Large wide hedges of

Rhododendron ponticum

were planted on the inside of the windbreak, much to everyone's regret as it has now become a weed, layering and seeding itself everywhere. Later on other plants were used for the same purpose, mainly

Griselinia littoralis

and

Escallonia macrantha

; these have given better results and are not so invasive.

Various conifers were used to create the woodland canopy:

Abies procera

,

Cupressus macrocarpa

,

Tsuga heterophylla

plus more

Pinus sylvestris

. If you try to imagine these species mixed with British indigenous types such as Oak, Birch and Rowan, you are beginning to picture Inverewe.

The windbreak consists of trees mainly of the same age and size, the result of minimal thinning and replanting in the beginning. Many of these are now tall enough to have their tops blasted by the winter gales; over 180 have been blown down in the past two years. Storm damage has been known in the past, but never on this scale.

When the National Trust took over some replanting was done, and trees lost in the recent disastrous storms are now being replaced, mainly with hardwoods of various types, including

Alnus incana

,

A. rubra

,

Nothofagus obliqua

,

N. procera

, plus Oak and Ash. Various sizes are being planted, three to eight years old, and hopefully this will result in a better windbreak as they will not all reach maturity at once. Another advantage is that, being deciduous, they will have a lighter head in winter, making them less susceptible to storm damage.

Once Osgood Mackenzie had established the windbreak he started to introduce exotics, and by the time of his death in 1922 it would appear that there were some one hundred different rhododendrons in the garden, a mixture of species and hybrids. These, along with a good many other plants, including Abutilons, Arbutus, Bamboos, Cordylines, Dicksonia, Embothriums, Eucryphias, Heves, Leptospermums, Olearias, Podocarpus, shrubby Senecios and of course his beloved Magnolias - most notably

M. campbellii

- provided the basis of a good collection. There were also many herbaceous plants and bulbs, but little or no records of them survive.

After his death, the work of looking after the garden was carried on by Mackenzie's daughter, Mairi T. Sawyer, until she died in 1953. She, like her father, must have been a forward-thinking person, for the year before she died she handed the garden and Inverewe estate as well as an endowment for its upkeep over to the National Trust for Scotland, thus providing a sound and secure future for the garden. Since then the plant collection has continued to grow, with the genus

Rhododendron

reaching in total about 550 different types, about 250 of them species, the rest hybrids.

|

|

Azaleas and Japanese maples

Photo by Barrie Porteous |

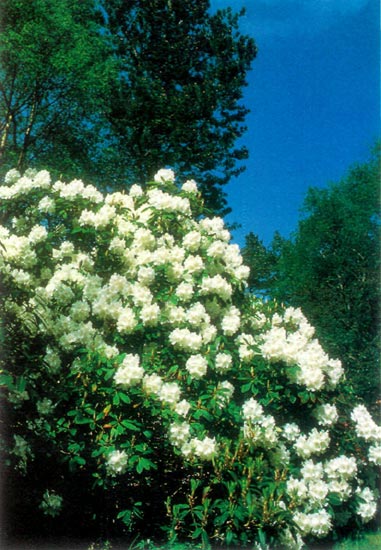

The central core of the rhododendron collection is made up of the following species, groves of which can be found throughout the garden: R. arboreum , R. barbatum , R. campanulatum , R. campylocarpum , R. falconeri , R. hodgsonii , R. luteum , R. niveum , R. sinogrande , R. sutchuenense , R. thomsonii and R. triflorum . The hybrids, of which there are far too many to mention, both old and modern, combine to a marvellous display of exuberant colour; plants of 'Christmas Cheer', 'Britannia' and 'Cynthia' combine with forms of 'Nobleanum' and large plants of 'Sappho' and its deep purple blotch, giving a display which is really too much for the eye to take. Newer hybrids, like 'Polar Bear' with its lovely scent and bright red peduncles, last in the mind for a long time. Smaller rhododendrons like 'Cilpinense', 'Snow Lady', 'Chikor' and species like R. williamsianum , R. yunnanense and R. leucaspis as well as members of the Lapponicum series are to be found all around the garden.

|

|

'Loderi King George'

Photo by Barrie Porteous |

The total plant collection consists of over 2500 different species and varieties covering all forms of plant life: trees, shrubs, bulbs, ferns and alpines as well as herbaceous plants and climbers. You will understand from this that it is impossible to mention everything that grows at Inverewe, so I hope you will forgive me for some self-indulgence as I write about the plants which excite me when I visit there.

One that immediately springs to mind is

Rhododendron oreodoxa

. This is a firm favourite with me as it is one of the earliest species to flower, with the advantage that the flowers will stand a little frost. The flower buds are blood red in colour, opening to reveal carmine, eventually fading to lilac.

Two other favourites of mine,

Rhododendron hodgsonii

and

Rhododendron sinogrande

, are right in the middle of the garden. The former is a magnificent plant 10 metres high and 12 metres across, surely one of the biggest on the British mainland. The plant of

R. sinogrande

is slightly smaller, but none the less impressive in shape and form. The foliage of these two plants is their biggest asset, those huge leaves 20-30 cm long and 10-15 cm wide, leathery in texture with prominent veins and woolly undersides; they glisten like jewels in the dappled sunlight. They both flower reasonable well in Inverewe, but I believe they do better at Brodick Castle in the Isle of Arran, another National Trust garden well worth a visit.

Not far from here in the part of the garden known as the "Peace Plot" (it was planted just after the Great War 1914-18) is a plant of

Rhododendron smithii

, a close relative of

R. barbatum

. However,

R. smithii

has delicate plum-coloured new growth in the spring, an added bonus to be enjoyed when the flowers have passed.

I am always looking for features in a plant that extend its season of usefulness; one other rhododendron which grows particularly well at Inverewe fits this mould admirably.

R. campylocarpum

with its greenish-blue foliage and lemon-yellow flowers is indeed a striking plant with good flower/foliage contrast, and after the flower is over the foliage itself makes a good contrast to the other plants around it.

Now, dare I say it? Enough of rhododendrons! What of other things?

For instance, New Zealanders, like

Olearis

. My favourite

Olearia semidentata

grows well at Inverewe; those aster-like purple and lilac flowers contrast well against its dark green foliage, which is curious in that it has a white woolly underside. There are other

Olearias

that do well in this highland oasis:

Olearia

x

haastii

,

O. macrodonta

,

O. phlogopappa

and

O.

x

scilloniensis

. When these are seen in combination with the Eucalyptus and Scots Pine they are quite breathtaking.

Another group of plants from the Southern Hemisphere that I am particularly fond of are the

Phormiums

; species like

P. tenax

and

P. colensoi

are extremely handsome with their sword-like leaves. Some of the newer hybrids, like 'Maori Sunrise', 'Yellow Wave' and 'Sundowner' are bright and colourful with red and yellow foliage. Planted near the gate, they are like a group of Highland warriors brandishing their claymores.

Another native of New Zealand growing near them arms itself well against intruders.

Aciphylla squarrosa

with its stiff needle-like foliage has a very architectural poise contrasting with the

Celmisias

, of which there are many.

Celmisia asteliaefolia

,

C. longifolia

and

C. monroi

all grow well, producing an abundance of pinkish-white daisy-like flowers. Their leaves are silvery-green, covered in fine hairs to protect them from the wind - an adaptation that is useful at Inverewe on occasions.

Before we leave plants from this part of the world, we must mention some of the many

Hebes

that grow at Inverewe. Such delights as

Hebe speciosa

'Alicia Amherst' with its deep purple racemes in late summer provide colour before the winter sets in, and the whipcord

Hebes

, like

H. ochracea

and

H. cupressoides

with their rope-like foliage, provide a contrast in shape and form to other plantings.

However, the plant that really spells Inverewe to me is

Eucalyptus coccifera

(Tasmanian Snow Cum), of which there are several planted near the main gate. How graceful they are, their silver-clad branches reaching skyward! These were planted by Osgood Mackenzie about 1900, and are now 23-24 metres high. One has a girth of 2.75 metres. Up in the woodland is a plant

E. gunnii

that is in excess of 26 metres and with its orange-coloured bark is most impressive. It has never been officially measured, as far as I know, but nevertheless it makes you feel quite humble when you stand beside it.

There are many patches of smaller plants in the woodland, including Cassiope, Gentians, Lilies, Phyllodoce, Primulas and Vacciniums too many to name. Lots of Meconopsis too, including my favourite M. x 'Sheldonii' with its delicate blue flowers which are almost translucent when the sun shines through them; a real joy later in the year.

|

|

Meconopsis

Photo by Barrie Porteous |

Other curiosities include a Cesneriad,

Asteranthera ovata

from Chile, growing happily outside at this latitude. This strange climber scrambles about the moist mossy rocks in several of the shady places in the garden. Its corolla is 5 to 7.5 cm long, tubular with four lobes. A reddish-pink in colour, it is quite vibrant against its background. However, it is one of those plants that will grow if it likes you and your conditions, if not it won't.

Also outside are Bromeliads, such as

Puya alpestris

with its metallic-blue flowers containing bright orange anthers: they look really alien rising above their prickly rosette of foliage. Another strange garden occupant from the same family is

Fascicularia pitcairnfolia

, again with viciously spiky foliage in the form of a rosette about 1 metre across, the inner leaves of which turn bright scarlet during the flowering period. The flowers themselves are turquoise blue, so tiny they are held deep in the centre of the rosette. The whole appearance is quite exotic. To look at them and then to the heatherclad mountains outside the garden is quite a contrast.

I cannot leave Inverewe without a mention of the Walled Garden, so much of it the work of human labour, most of the soil having been brought in creels carried on the workers' backs many years ago. The Walled Garden contains many tender plants, including

Echium wildpretii

from the Canary Islands. There are also Cordylines, underplanted with herbs for the kitchen. The Shrub and Climbing Roses which are intertwined with Clematis give colour and fragrance in the evening. And the herbaceous border, all 80 metres of it, full of contrast in both plant material and colour, deep blue Aconitums, majestic Delphiniums, bright red Astilbes, luscious Hostas, golden Achilleas and many, many more traditional herbaceous border plants, creating a tapestry of colour. On the terrace behind them grows a wide and varied range of good looking vegetables, all nurtured on seaweed. The walls too are not wasted: each autumn they are laden with apples, plums and pears. These look down on beds of strawberries and rows of raspberries; not the place for someone on a diet!

How does one sum all this up? Contrast! Inverewe is about contrast. Contrast in climate to the one normally found at this latitude; contrast in plant content, contrast in colour and contrast to the landscape it sits in. But strangely enough, despite all these contrasts, it is a very harmonious and peaceful place to live and work in, and of course, to visit. Perhaps it's something to do with the romance and mystique of the Scottish Highlands; I don't know, but I do know you would enjoy a visit. I hope I have tempted you.

— ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS — I would like to thank both the National Trust for Scotland and Mr. P. Clough, the present Head Gardener at Inverewe, for their help with this article and for allowing me such free access to the Garden's records.

David R. Mitchell is Head Gardener at the Suntrap Horticultural Centre in Edinburgh.