A Brief Visit To Yakushima

Clifford Desch, Ph.D.

Conway, Massachusetts

Geography and Geology

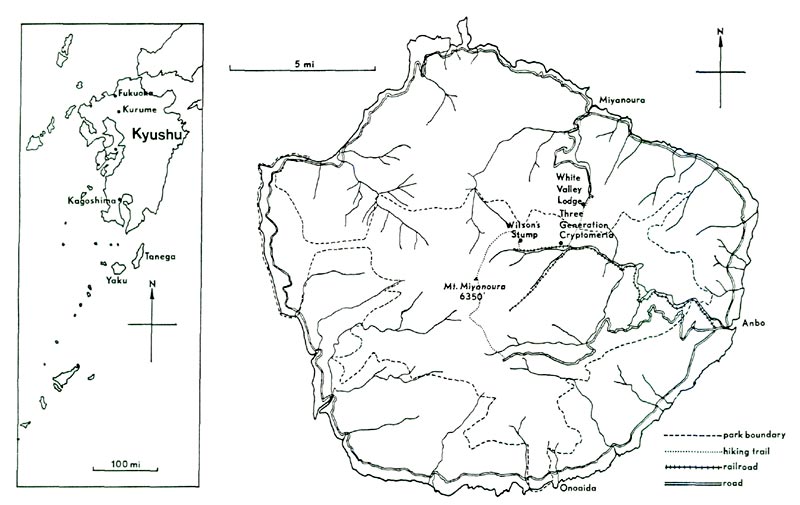

There are probably thousands of islands in the oceans of the globe with a seventeen mile diameter, but none is so renowned to rhododendron growers as Yaku. This island is a member of the Ryukyu Island chain which extends in a sweeping, 700 mile arc from southern Kyushu to Taiwan. Although only the third largest of the group, Yaku (208 square miles) has the highest elevation (6,350 feet). In comparison, Okinawa, the largest island of the chain (454 square miles), has an elevation of only 1650 feet. Yaku is a very rugged island composed primarily of acidic granitic rock which was pushed above sea level in the earliest Miocene Epoch (26,000,000 years ago). At this time it was joined with the main Japanese-Asian land mass. It first became insular in the early Pleistocene (7,000,000 years ago), was rejoined with the Japanese-Asian land mass during the ice ages when glaciers lowered the global ocean levels, and achieved its present insular condition about 10,000 years ago. (Note: "-shima" in Japanese means island. Thus, to say Yakushima Island is redundant).

Ryukyu Vegetation

The geologic history and climate strongly influence the vegetation of the Ryukyus. Yaku, with its great elevation, has pronounced altitudinal zones. The floral and faunal distribution of warmer southern and cooler northern life forms as found on Yaku can only be explained by formation of land bridges and subsequent inundations. Since Yaku Island's insulation after the last Ice Age a number of endemic plant forms have evolved such as

Rhododendron yakushimanum

and

Asarum yakushimense

. It is an interesting thought that while one is driving along the coast road, which encircles the island, and observing evergreen fig trees and palms, that a few miles inland and 5,000 feet above there are plants hardy enough to thrive in the colder areas of New England. Overall, the climate of Yaku Island can be described as mild and wet.

The vegetation of the Ryjkyus is considered as transitional between Taiwan and Japan. Actually floral and faunal distributions on these islands are due to southern migrations when they were contiguous with Japan and northern migrations when they were joined with the Taiwan/ China land mass. The Japanese monkey,

Macaca fuscata

, is found on all islands from Yaku to Hokkaido. Another northern element,

Rhododendron metternichii

has a similar distribution but is absent from Hokkaido.

Rhododendron yakushimanum

is closely related to

R. metternichii

and may have evolved from it. The lower altitudinal forms (to 2,600 feet) of

R. yakushimanum

(= var.

intermedium

) have large leaves with a thin indumentum and appear very similar to

R. metternichii

. According to Chamberlain (1982), these two rhododendrons may be conspecific. In the English version of J. Ohwi's tome,

The Flora of Japan

, it is referred to as

R. metternichii

var.

yakushimanum

.

My first acquaintance with Yaku Island came when I read Dr. Fred Serbin's brief article on

Rhododendron yakushimanum

in the Brooklyn Botanic Garden's

Handbook on Rhododendrons and Their Relatives

. I was impressed with the beauty of this rhododendron and the fact that parts of the island get 400 inches of rain per year. Little did I realize then that eleven years later I would be getting soaked to the skin on this rainy island in the South China Sea.

Dr. Kaku's Invitation

My opportunity to visit Yaku Island came through my friend, Dr. Shosuke Kaku, professor of botany at Kyushu University in Fukuoka. Dr. Kaku does research on the physiology of cold hardiness of tissues and organs of rhododendrons. He invited me to visit him on my return home from my sabbatical leave in New Zealand in 1984 where I had been engaged in research on parasitic mites of mammals.

My wife, Cathy, and I flew to Tokyo and from there took the Shin-kansen, or bullet train, to Fukuoka. This is the best way to travel in Japan and the trains have very few empty seats even though there is a departure on this southern run every hour. From Hiroshima to the end of Honshu many of the sparsely wooded hillsides were mottled with purple masses of blooming

Rhododendron reticulatum

. The train is clean, comfortable, quiet, fast (120 m.p.h.) and on time! The precision of time and space with which these trains are run is such that the position of the doors of the cars is pre-marked on the station platform. This makes it convenient for the person meeting you at the train because by knowing your reserved seat assignment he can meet you at the car door when you get off. Shosuke was waiting when we arrived and took us by taxi to our hotel. This was a government employee hotel and, although very comfortable, was not oriented to non-Japanese speaking tourists: no signs or menus in English. (Most hotels in the U.S. don't translate their menus into Japanese either). The inability to read even simple signs in Congi makes one completely illiterate and thus, getting around on one's own can be very difficult. There is no such thing as a Japanese-to-English dictionary because Congi cannot be alphabetized. We were lucky to have Shosuke as our guide and he organized almost all of our travels.

After getting us settled in the hotel in the late afternoon, Shosuke took his leave planning to return in the morning for a trip to Kurume Agricultural Research Station. We had dinner in a sushi restaurant and bought some beer to drink while watching a baseball game on TV. This was the only Japanese program I could understand as all their baseball terms are English: first base, home run, strike out, etc.

Visit to Kurume

In the morning we taxied to the train station where Shosuke's technician, Mari Inoue, joined us for the trip to Kurume via the local line. At the agricultural station we met Dr. Yamaguchi who is developing new generations in the breeding program of the already-complex Japanese azaleas. After talking for a while we all loaded into a government station wagon and drove into the countryside to Doi Gardens. This is a nursery operated by Mr. Doi who owns a large retail camera chain and lives in Fukuoka. He was not at the nursery but we had green tea with the manager and his wife. Many of the plants are imported from outside Japan and grown in containers in greenhouses. Mr. Doi's favorite rhododendron is

R. kiusianum

of which he has many clones.

On the return trip to Kurume we passed through a small town noted for a national living treasure in the courtyard of a temple. This treasure is a 600 year old

Wisteria chinensis

. It has an enormous, multistemmed trunk with branches fanning out on trellises to cover the one acre courtyard - and it was in full bloom. What a sight! Low up on the surrounding hills blooming wisterias could be seen climbing over and through the trees. Back at Kurume we took an abbreviated tour of the greenhouses and azalea test plots as it was becoming dark. Then went by train back to Fukuoka to await the next day when we would depart for Kagoshima.

Kagoshima - Southern Kyushu

Kagoshima is a seven hour train ride south from Fukuoka. The route passes much of its distance along the scenic west coast of Kyushu. Orange groves and wild

Cycas revoluta

are indicative of the mild climate of southern Kyushu. The port city of Kagoshima lies on the northwest shore of a great inlet, Kagoshima Bay, from the South China Sea. Directly across the bay from this city of one million inhabitants is Mt. Sakurajima, one of the five most active volcanoes in Japan. It last erupted in 1946 but its summit is always shrouded in a plume of airborne ash. Mt. Sakurajima is included in the Kirishima-Yaku National Park which is made up of five non-contiguous parts including Yaku Island.

On the afternoon of our arrival in Kagoshima we visited the Iso Garden built in 1660 by the Shimazu shogun. It relies heavily for effect on the bay and Mt. Sakurajima as a backdrop. The Japanese refer to this technique as "borrowed scenery." There are many large, almost abstract looking stone lanterns made from the native volcanic rock. The very large cycads in the garden must be very old.

The next day we taxied to Kagoshima University to visit Drs. Kenichi Arisumi and Eisuke Matsuo in the Laboratory of Ornamental Horticulture and Floriculture. Kagoshima (31 degrees N) has a winter-summer temperature equivalent to Jacksonville, Florida. Drs. Arisumi and Matsuo are engaged in breeding for heat resistant rhododendrons (see Dr. Arisumi's article on this subject in

ARS Journal

Vol. 39: 4, Fall 1985). Drought is not a problem as the area receives 80-120 inches of rain per year. In Dr. Arisumi's office we sipped the ubiquitous green tea and waited for a bus load of American rhododendron growers to arrive so we could tour the facilities together. To our surprise the bus contained a group from the American Rhododendron Society led by George Ring and included a friend, Kathy Freeland. This coincidence immediately called to mind the cliche, "It's a small world." (Ten days later we met again while touring the Toshogu Shrine at Nikko, 75 miles north of Tokyo).

From the University we took a bus into downtown Kagoshima to obtain money at a bank. Banks will charge cash to an American credit card but very few businesses outside of cities will accept them. A good word to the non-group traveler in Japan: bring plenty of cash because one cannot always count on being able to use a credit card. Then on to a book store to buy a map of Yaku Island - alas, nothing in English. A short taxi ride brought us to the ferry dock where we purchased second class tickets to Yaku Island and waited an hour before boarding the 200 foot ship. Most of the 200 or so passengers were locals with a few young Japanese backpackers scattered in. We were the only foreigners. Small trucks and vans were shoe-horned onto the aft deck loaded with supplies for local businesses and cottage industries. Heavier freight, such as ceramic roof tiles, were lowered into the ship's hold. The beginning of the four hour ferry trip treats one to magnificent views of Mt. Sakurajima followed by 40 miles of verdant, rough volcanic terrain along the shores of Kagoshima Bay before entering the Van Diemen Strait (Osumi Strait) of the South China Sea. The ship headed due south towards Yaku Island passing small volcanic islands to the west and a long, flat-topped island, Tanega, to the east where Europeans first set foot on Japanese soil: three shipwrecked Portuguese sailors in 1543. The sea and the islands were shrouded in low clouds with sporadic patches of rain and sunshine. About 6:00 p.m. a mountainous island appeared outlined in the clouds over the starboard bow. It was Yaku Island.

|

Yaku Island Arrival

The ruggedness of this densely vegetated island became apparent as we approached closer and the clouds parted somewhat as we cleared the breakwater of the main port, Miyanoura, on the northeast coast. This town, very small by Japanese standards, houses about half of the island's 16,000 residents. The economy of Yaku Island is based on fishing, agriculture and forestry. We checked into our ryokan (traditional Japanese hotel) and had a ten-dish meal which could aptly be described as dining on an abbreviated version of a marine biology course: squid strips, whole snails, sliced rings of sea cucumber, brown seaweed, red seaweed, raw fish and various other unidentifiables. Across the street fishermen were unloading their daily catch; all seafood is very fresh, less than one day old.

Yaku Island is nearly circular with a paved, two-lane road closely paralleling the shore all the way around (see map). The island's three towns, Miyanoura, Anbo (east) and Onoaida (south) lie on this road. The coast line is very rugged on all but the southwest shore which has beautiful sandy beaches. Agriculture is based along the road on the eastern half of the island on flat marine terraces pushed up from the sea floor during the island's post-glacial uplifting.

|

|

View from ferry entering harbor at Miyanoura.

Cut of road leading to White Valley can be seen half way up mountain at left in background. Photo by Clifford Desch |

Shosuke had arranged for us to meet Mr. Mioura, the young (and only) ranger for the Yaku Island portion of the National Park, at his office in Anbo. The park headquarters office is in a small brick house where Mr. Mioura lives with his wife. He had been transferred here a few years ago from Nikko National Park. During his time on Yaku he has explored all parts of the island and developed a good knowledge of its diverse and varied flora. A total of 1,280 plant taxa have been reported on Yaku Island with about 50 species being endemic, including Rhododendron yakushimanum . The national park is confined to the center of the island except for a large block along the west coast line and a small area on the south coast near Onoaida (see map).

Exploring by Four Wheel Drive

This and the following day were holidays in Japan (Emperor's birthday) and Mr. Mioura graciously offered to be our guide during his time off. We loaded our gear into the four-wheel drive park station wagon and drove inland. Soon the pavement ended and the road began to climb. In short order it became rough, steep in places and winding. Upwards from 2600 feet there was steady rain; nothing unusual for this high rainfall region. The vegetation on the precipitous slopes is luxuriant but not tropical in appearance. Across the narrow valleys the lush green was broken by rock outcrops and scattered blooming

Symplochos

sp. and

Prunus jamasakura

var.

chikusiensis

. Along the side of the road, where there is little over story shade, eight foot tall

Rhododendron tashiroi

was in full bloom. The pale pink flowers show little color variation from plant to plant. The road ended at 4,600 feet altitude where it intersects a trail to Mt. Miyanoura, the highest peak and the habitat of

R. yakushimanum

. We left the car with enthusiasm, which was quickly dampened by the cold rain, and set forth into the dripping forest with large

Cryptomeria japonica

as the major canopy tree.

Stewartia monodelpha

formed a conspicuous part of the taller understory with its beautiful, cinnamon-colored bark. Tangles of

Rhododendron yakushimanum

var.

intermedium

,

R. keiskei

and

Pieris japonica

formed the low understory. None were in bloom at this location. The

R. yakushimanum

var.

intermedium

has large leaves with gray-silver indumentum varying from plastered to felty. After walking along the trail for about a mile in the pouring rain we decided to return to the car and tour around the island along the coast road; maybe we would have better weather the next day. At this time I had only ASA64 film and the light level due to the thick clouds and forest was so low that I could not take pictures. In Anbo I was able to purchase faster film.

|

|

Rhododendron tashiroi

along road bank.

Photo by Clifford Desch |

Flora and Fauna

About half way down to sea level we encountered a band of twenty Japanese macaques (

Macaca fuscata

) sitting nonchalantly beside a guard rail at the edge of the road. All of us except Mr. Mioura were very surprised to see them. It is said that these monkeys outnumber the human inhabitants on Yaku Island. We stopped the car to get out and take some pictures. They did not run off and let us approach quite close, but not too close. A large male jumped on the hood of the car and sat there looking at us. Shosuke moved in close to take a photo and the monkey lunged at him. This aggressive display also gave us an impressive closeup of his gaping mouth with its array of large teeth! At this point we thought it wise to reenter the car. The large male jumped from the car and the troop watched us drive away.

Upon returning to the coast road we drove a short distance northeast of Anbo to a station of

Asarum kumageanum

. This was on the south side of a small wooded ravine at about 350 feet altitude. The flowers are superficially like those of the wild ginger in New England,

A. canadense

, but the foliage is beautifully mottled and every plant has a unique pattern. Barry Yinger in his fine monograph on the asarums of Japan expresses his opinion that this is the "most attractive evergreen herbaceous foliage plant hardy in a temperate climate." I concur. It grows only on Yaku and a few small, nearby islands.

We now proceeded around the island in a clockwise direction stopping in Onoaida to view a very large

Ficus microcarpa

with many aerial roots. Growing at the base of this tree and twining through the aerial roots was

Piper kadzura

with prominent veins in the deep green leaves. The road along the southern coast runs at between 150 to 225 feet above sea level. At the bend where it starts north along the west shore it drops down to nearly sea level and passes on the inland side of beautiful, deserted sandy beaches. At this point it was sunny and warm. The road crosses an inlet and rises to its former elevation with fine overlooks of the sea.

Styrax japonica

and

Caesalpinia japonica

grow along the road and were in full bloom although the latter was too tall to get a close look at the flowers.

|

|

Asarum yakushimense

in bloom; flower color

on different plants range from predominantly maroon to dull yellow. Photo by Clifford Desch |

Just before the road crossed the above mentioned inlet we took a small road inland to an area which was being logged off at 3,300 feet altitude. The road was unpaved but well constructed. We drove to the very end which cut through a stand of 25 foot high, blooming Pieris japonica . In this area they formed a canopy plant and looked odd where the road had cut through because they had tall, spindly trunks with branches and leaves only at the crown. It was here that Mr. Mioura showed us a large colony of Asarum yakushimense . They grow near the logging road and probably will be destroyed by the lumbering operation. This area is not within the national park. Asarum yakushimense has deep green leaves without mottling. The flowers, however, are large and variable in their ground color: basically maroon with varying amounts of yellow markings. To quote Barry Yinger again, "...a pot of this species in flower stops every plant enthusiast in his tracks." Again, I concur. This was a forested area on an east facing slope. Nearby were plants of Berberis thunbergii , a small white orchid and, perched on the trunk of a tree, a bird-nest fern, Asplenium nidus . The thought that all this would be destroyed by logging was depressing. We returned to the coast road and continued our clockwise route. We crossed a rocky stream bed where Rhododendron indicum was growing in the sandy deposits among large, round boulders. It was evident that these plants were periodically flooded by large volumes of water but were secure because they were so tightly wedged among the rocks. Nine were in bloom. We could find no small seedlings. Upon reaching the north shore it began to rain again and continued for the remainder of our trip back to Anbo. Mr. Mioura dropped us off at a ryokan about one mile south of that town. This establishment had Japanese-style rooms (tatami mats on the floor, futons for sleeping instead of beds, a low table, no chairs, etc.), communal dining room and guests use the town bath just up the street. The water in the bath was wonderful; its source was a natural hot spring. Japanese baths are like shallow swimming pools where one sits with hot water up to one's neck. The clerk at the ryokan remarked to Shosuke that Cathy and I were the first non-Japanese guests since she began working there three months before.

White Valley by Foot

The next day was the Emperor's 83rd birthday, 29 April 1984. We had our Japanese-style breakfast and took a taxi to Mr. Mioura's house. His wife made us green tea and we drove to Miyanoura to drop our things off at a different ryokan. From there we drove inland to the south to just over 2,000 feet in altitude. This road followed the north slope of the steep sided White Valley with spectacular views of Miyanoura and the sea off in the distance. We proceeded up the trail which crisscrossed the White Valley stream, a fast moving torrent. It was raining again but we were determined to keep going. The trail was good but slippery in spots where it crossed large rock outcrops or boulders. Some places were ankle-deep mud or standing water. We were to spend ten hours like this but were so wet in the first few that the extra time didn't matter.

Large, twelve foot tall plants of blooming

Rhododendron keiskei

overhung the stream. The trail was littered with brilliant red, waxy flowers of

Camellia japonica

which had fallen from overhead. No color variations were seen. The rain became very heavy at times. We came upon the White Valley lodge, a simple, but dry building in the national park maintained by a keeper and his wife. They invited us in for tea and fried sweet potato sticks. The trail had its ups and downs; somehow there seemed to be more up than down! We passed blooming plants of

Arisaema japonica

,

A. nana

,

Rhododendron tashiroi

and

R. keiskei

. Even though these two rhododendrons occur side-by-side and bloom simultaneously there is no indication of any hybridization.

Rhododendron keiskei

was named by Miquel in 1866 in honor of the Japanese botanist Ito Keisuke (1803-1900). Note the spelling of the two names is different. The "u" in Keisuke's name is silent in Japanese pronunciation and so the spelling for the rhododendron name is phonetic.

After a few hours, the trail came out onto a small gage railroad track. This is used to haul logs down to Anbo. The walking was now quite level but still not easy because the ties were not spaced at a convenient stride distance and in many places everything else was underwater. We had lunch in a crude woodcutters' accommodation which was filled with a Japanese hiking group trying to keep dry. Outside the front door was a very large repository of empty saki bottles. Mr. Mioura borrowed an umbrella for me from one of this group; they did not plan to go out in the rain that day.

|

|

North Valley as seen from the tracks of the logging railroad.

Approximately 2,800' altitude. Photo by Clifford Desch |

The railroad tracks follow the North Valley about 200 feet above the rushing stream. The views along and across the valley were very beautiful as everything was misty in the pouring rain. Large

Abies tirma

,

Cryptomeria japonica

and

Tsuga sieboldii

stood out along the ridges. This area of the national park was extensively logged following World War II. There are still signs of continued cutting of

C. japonica

.

Rhododendron tashiroi

and

R. keiskei

bloom in profusion in areas where the trees have been thinned along the rail line. The stumps of some of the

C. japonica

which had been felled many years ago are enormous; ones fifteen feet in diameter are not uncommon. On the banks beside the tracks bloomed

Arisaema thunbergii

and

A. japonica

, and numerous seedlings of all the above mentioned woody plants.

Trochodendron aralioides

was common in the understory just beyond the cleared area along the tracks.

One

Cryptomeria japonica

stump complex was of particular interest. It represented three generations. A five foot diameter tree (about 400 years old) was growing from the cut top of a fifteen foot diameter stump. The larger tree had grown up around a fallen six foot diameter tree which had long since rotted away.

|

|

Dr. Shosuke Kaku standing besides

"Wilson's Stump" at 3,470'. Photo by Clifford Desch |

Wilson's Stump

Time was not sufficient on this day to reach the

Rhododendron yakushimanum

area on Mt. Miyanoura so we set our goal to visit a landmark called Wilson's stump. Just before the end of the rail line we took a trail heading up the mountain in a northerly direction. This led us into an area which appeared to have never been cut over. After about a half mile of scampering up wet rock faces and skirting muddy depressions we came to a

Cryptomeria japonica

stump twenty feet in diameter which is said to have been cut down in 1586! The national park brochure says that Ernest H. Wilson visited this site and the stump is named in his honor. I can find no mention of this in Wilson's book on the Orient, however. The stump is completely moss covered and one can walk into the spacious rotted out center in which has been placed a small Buddhist shrine. We took photos of each other by the stump in this dripping wet, moss covered, beautiful forest and then began our trek back to the car. We stopped at the White Valley forest lodge for another cup of tea and arrived at the parking lot at 6:30 in the evening. There was a group of school children under a shelter there and they invited us for more tea. They enjoyed the company of a foreigner very much as it allowed them to practice their English. Japanese learn to read and write English quite well in school but have very little opportunity to practice speaking it. The trip down to Miyanoura in the car allowed us time to rest and reflect on the good feelings from having spent the past ten hours in the rain. I think the rain sharpened our focus on the plants and their beautiful surroundings. The memories I have of this marvelous island in the cloud banks of the South China Sea will long remain vivid in my mind. At the ryokan in Miyanoura we said our goodbyes to Mr. Mioura who had so kindly spent his two vacation days leading us through the rain. I think his love of nature is such that he really didn't look on this as a hardship.

Until Next Time

The next morning was anticlimactic as we had to pack, eat breakfast and taxi to the pier for the 9 o'clock ferry to Kagoshima. As the ferry entered the open water from the mouth of the harbor, the clouds were high enough to reveal the rugged green mountains we had tramped through the day before. Although I sincerely regret not having had the opportunity to see

Rhododendron yakushimanum

in its home near the summit of Mt. Miyanoura, I am left with the positive thought that this provides the excuse to revisit the island in the future to fulfill this desire. Some day!

References

Chamberlain, D.F. 1982. A revision of Rhododendron. II. Subgenus Hymenanthes. Notes RBG Edinb. 39: 209-486.

Ohwi, J. 1984. Flora of Japan. (In English). Eds. F.C. Meyer and E.H. Walker. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. pp. 1067.

Serbin, A.F. 1971. An exceptional dwarf rhododendron. In:

Handbook on Rhododendrons and Their Relatives

. Eds. G.E. Jones and F. McCourty, Jr. Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Brooklyn, New York, pp. 81-82.

Yinger, B.R. 1983. A horticultural monograph of the genus

Asarum sensulato

, in Japan. Master of Science in Ornamental Horticulture, University of Delaware, pp. 290.

Dr. Desch is a member of the biology faculty at the University of Connecticut, West Hartford, Connecticut and past president of the Connecticut Chapter, ARS.