In Memoriam: The Remarkable Mr. Nearing

David C. Leach

North Madison, Ohio

Guy Nearing, the last of the legendary American pioneers in the study of rhododendrons, died at the age of 96 on March 19, 1986. He had been a patient in a nursing home for many years.

When he closed his New Jersey nursery and retired from active involvement with the plants he knew so well, he could look back on a life that had been full by any standard. His reminiscences could bring the renowned horticulturist the glow of accomplishment. In angry defiance of repeated disasters so appalling that they call to mind a classic tragedy, Nearing achieved the kind of life he always admired; he had the distinction of being an outstanding figure in a half dozen fields so varied that his talent was awesome to contemplate. To most observers, he was the most remarkable person to appear on the horticultural scene in generations.

A slight, graying man, lean and fit, his last stand against adversity was a one-man nursery in Ramsey, New Jersey, growing and breeding rhododendrons. Visitors received an immediate impression of alert intelligence and coiled-spring energy. His conversation was as brisk as his walk. The novice received practical advice. The expert conversed on an advanced technical level with an authority who was an early recipient of the Gold Medal of The American Rhododendron Society.

|

|

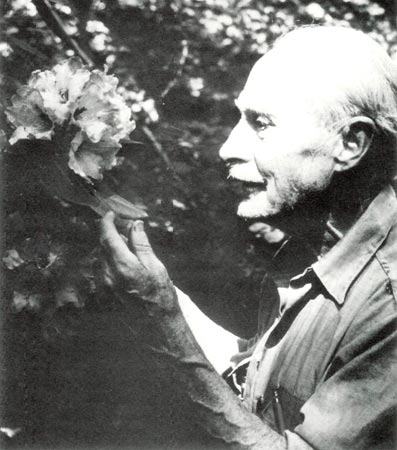

Guy Nearing with his hybrid 'Rochelle',

Ramsey, New Jersey, about 1974. Photo by Ed Walbrecht |

After a long day of labor in his nursery, Nearing, well into his seventies, was apt to start out on a night of arduous folk dancing. His picture, often in costume, appeared in newspapers from time to time and The Nearing Circle Waltz, often recorded, has been used by dance groups from coast to coast. The folk dancing was an outgrowth of an early athletic talent, a happy combination of agility and a sense of the dramatic which held over from Nearing's days as a Shakespearean actor.

Nearing was born January 22, 1890, at Morris Run in Tioga County, Pennsylvania, into a well-to-do family marked by colorful characters and strong intellectual interests. As a boy he became an amateur naturalist, roaming the countryside, examining and collecting plants in the woods and fields, showing the same enthusiasm and curiosity for the natural world which is so evident in him today.

In 1911 he entered the University of Pennsylvania and soon drew attention by the brilliance of his work. His election to Phi Beta Kappa was almost routine for a student of such conspicuous talent. Not so routine was his athletic ability. By his senior year the famous track coach, Mike Murphy, had him headed for the Olympics as a champion miler, and then came the first jarring blow of a malignant fate that was to lash out at him again and again, for decades. He was struck blind. With his mother reading his assignments to him, he finished his senior year and graduated with distinction.

Twice he tried to re-enter the academic world as his vision slowly improved but graduate school study was too much for his weakened eyes and he resolutely abandoned any hope of achieving the assistant professor's chair at the University of Pennsylvania that was to be offered to him if he got his doctorate.

Turning his literary flair to practical use, Nearing began work with a series of national publications, among them

Mentor Magazine

and

Harper's Bazaar

. After an interim hitch in the Army which ended when the sight of one eye was completely and permanently lost, he was launched on an auspicious career in a publicity agency in 1918 when he was stricken with tuberculosis. Rejecting the Army's offer of hospital care he found a home site, pitched a tent and with his own hands built a house into which he moved his bride. His tuberculosis was conquered while he worked as an artisan in the construction of the building.

With renewed health Nearing went into advertising and his ability soon lured the accounts of large national corporations into his agency. His contemporaries on Madison Avenue still remember his work for Campbell's Soup and he is widely regarded as the originator of valuable advertising techniques which were unique at that time. And so success, big and profitable, was again at his doorstep when, for the third time, the hand of fate descended. If he was to live, the doctors told him, he must change his work to outdoor activity.

So it was that in 1928 Guy Nearing turned once again to the plants he had loved in his youth. He opened a nursery at Arden, Delaware. Within a year Nearing had become a recognized expert on hollies. The nursery acquired a reputation as a source for new, rare and fine plants and the owner a widening prestige as a reputable advisor on horticultural matters. In 1929 the Guyencourt Nurseries absorbed Nearing's enterprise and together they began to propagate own-root rhododendrons on an immense scale. And once again the man was struck down. The nursery industry all but disintegrated in the general debacle of the great depression. The Guyencourt firm was dissolved. The program that had begun so promisingly ended in bleak defeat, just another victim of the nation-wide economic disaster.

But from this period came an invention, the Nearing Propagating Frame, that has since become a standard device for the rooting of cuttings in the nursery industry. An outdoor frame of special design with a sloping hood superstructure, in Nearing's hands it became the first commercially successful method of rooting rhododendron cuttings, freeing the nursery industry of dependence on imported grafted plants. Nearing was the first to propose the wounding of cuttings and he pioneered other propagation techniques that have enriched the professional growers of America to an extent that can scarcely be estimated.

After the collapse at Guyencourt, Nearing once again started a small nursery, this time at Ridgewood, New Jersey. His creative talent turned to the production of new and more beautiful rhododendrons, and he began hybridizing on a large scale. Hundreds of crosses were made, tens of thousands of plants were grown. Species newly discovered in Asia were tested by the score as he sought to isolate forms that would be hardy in the New Jersey climate. Again his nursery became a focus of interest for gardeners throughout the East, and Nearing added to his other accomplishments an international reputation as a rhododendron authority.

In the meantime he had been studying fungi as a hobby and had written some popular articles about them. His characteristic drive produced such a comprehensive knowledge of the subject that he wrote

The Lichen Book

, illustrated it with 700 of his own line drawings, printed and published it himself. The project took almost ten years and today the work is considered a classic. It is out of print now but there can be no second edition because the malignant fate which had hounded him since the blindness of his college days intervened yet again. A flash flood destroyed his nursery in 1945 and with it the engravings and drawings for

The Lichen Book

. The splendid rhododendron hybrids that he had created in ten years of concentrated effort were almost all lost. The Nearing hybrids that are now so highly regarded by specialists were salvaged and sold after the general disaster and eventually introduced commercially, solely through recognition of their value in the gardens of their owners.

For the next four years Nearing was a resident naturalist at Greenbrook Sanctuary on the Hudson River's Palisades. His nursery at Ramsey was opened in 1950. For the third time he has assembled a remarkable array of rare rhododendron species and exotic hybrids of his own creation. Specialists all over the world knew his work, visited his nursery and kept in touch with him by mail. Experienced gardeners sought his plants, grown with great care in the traditional way without the speed-up of modern conveyor-belt production methods.

I first knew Nearing through correspondence many years ago when I wrote to him about a problem which had arisen in connection with my own work as a rhododendron breeder. Back came a long reply so clear, so accurate and so comprehensive that I realized at once it could only have been written by a man of extraordinary generosity and competence. And so he proved to be, over and over again, when we later met and became friends.

The stories about him are legion. A traveling companion with whom he was touring England tells with affectionate humor of their first morning as roommates, when he was awakened in the foggy dawn to an icy gale blowing through the wide-open windows and Nearing enthusiastically hopping around the bedroom on his haunches, flinging out his legs rhythmically in a first-rate performance of the traditional Russian Cossack dance. The subsequent repertoire must have been entertaining because they stayed together as roommates for the remainder of the trip through England.

When Nearing first called at the nursery of the well-known rhododendron hybridist, Joseph Gable, he walked up to Gable and without a word of greeting or identification launched a barrage of questions about rhododendrons that stunned the unsuspecting host. Such a vigorous discussion developed that it was not until much later that Gable had any idea that his caller was Guy Nearing. It was a typical Nearing gambit, the intense concentration on the purpose of his visit having completely eliminated from his mind any frivolous distractions. The two men became fast friends, sharing seeds and helping each other in every possible way in their hybridizing programs.

Gardeners everywhere sadly ponder what might have been whenever they think of the few Nearing hybrids that escaped the 1945 flood. The survivors that did finally come on the market are universally admired: 'Ramapo' and 'Purple Gem', the first "blue"-flowered dwarfs to capture in hardy form the charms of the alpine species from the mountain passes of Asia; the delightful pink-and-white 'Windbeam' and 'Wyanokie', two more valuable additions to the small list of dwarf rhododendrons available to meet modern landscaping needs in cold climates; and the Guyencourt series: 'Brandywine', 'Chesapeake', 'Delaware', 'Hockessin', 'Lenape', and 'Montchanin', small-leaved hybrids not over two feet tall ranging in flower color from white through pale yellow to rose. 'Rochelle' is probably the best known of his large leaved hybrids. Rhododendron hobbyists fervently hope that Nearing's productions toward the end of his hybridizing efforts, few yet distributed, will equal those of the 1935-45 period.

Through the years I have continued to learn of new and surprising facets of this remarkable man: that he was a chess master; that he published five volumes of verse; that he learned Braille against the possibility that he might eventually lose his remaining sight; that he was an accomplished artisan as a blacksmith in ornamental iron. Lecturer and author of innumerable botanical articles, artist and scientist, theorist and practical nurseryman, his life was a vivid demonstration that the Renaissance ideal of the complete man had not vanished in the Age of Specialization.

A star-crossed figure to the end, the fates dealt him a final blow at the finish of his active career in horticulture when his home was utterly destroyed by fire. Even so, he triumphed yet again over this last cruel calamity, in a sense. He had given to me and to others the codes for his plants and crosses, and had established a regime with a group of New Jersey hobbyists to preserve and distribute the best of his hybrids and species forms. He was the embodiment of proof that courage and determination can produce, despite all obstacles, a lifetime of lustrous accomplishments.