Archibald Menzies & the Discovery of Rhododendron macrophyllum: Part 2

Clive Justice

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

In Part One of this article,

Journal ARS

, Vol. 45, No. 3, the author told of Archibald Menzies' discovery of

R. macrophyllum

at Discovery Bay, Washington, in 1792 while serving as botanist and ship surgeon for Captain George Vancouver. Menzies' botanizing took him from the southern waters of Puget Sound to waters just north of Vancouver Island.

The Pacific rhododendron received no rave reviews from Menzies, but it was the Hookers of Kew who almost "did in" the Northwest native. Clive Justice of Vancouver, B.C., continues the story of

R. macrophyllum

- a narrative he first delivered at the ARS Western Regional Conference at Whistler Mountain, British Columbia, in October 1990.

The coastal limits of

Rhododendron macrophyllum's

range are the north and east coast of the Olympic Peninsula and Whidbey Island on the other side of Puget Sound. As a consequence Menzies never collected any seed. Menzies left for the north end of Georgia Straits on June 19th (flowering had hardly finished), and he never returned to Puget Sound.

After Menzies' return home to England in 1794, Captain George Vancouver as expedition leader had first call on all journals kept on the voyage. As a result, Menzies' journal was handed over to the Captain with the permission of Sir Joseph Banks, director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

A charge of insubordination (subsequently dropped) was brought by Vancouver against Menzies for his anger at the Captain over the loss of plants in a South Atlantic deluge on the 1794 return voyage. All the living plants Menzies had collected in the Pacific Northwest and Hawaii, which he had placed and carefully tended in the Banks plant frame on Discovery's quarter deck, were lost. You could hardly blame him for being angry and chewing out Vancouver after seeing three years of collecting destroyed because the man detailed to covering and uncovering the plant frame with a canvas had been assigned to other duties by the Captain.

After this Menzies seems to have lost much of his interest in botany. Instead he turned his full attention to his duties as a Naval Surgeon.

Menzies' collections of pressed specimens went into the Banks herbarium, there to stay more or less unlooked at until after momentous non-botanical events that occurred in the first two decades of the 19th century - the Battle of Trafalgar, the War of 1812 and Waterloo. In 1820, the year of Banks' death, Sir William, the senior Hooker, took them on to compile his great work on the flora of North America,

Flora Boreali-Americana

. This series appeared over a 10-year period from 1829 to 1840. It was a dry listing by plant family with descriptions in Latin and was hardly a popular best seller for the gardening public.

Menzies served as surgeon on the West Indies station in Kingston, Jamaica. After he was invalided out of the Navy he married and set up practice as a physician in London. His was a busy practice and he had little time for botanical pursuits. However, both John Scouler and David Douglas consulted Menzies in regard to the Northwest coast before they undertook their voyage together to the Pacific Northwest in 1824 on the Hudson's Bay Company supply ship William and Ann. Scouler was surgeon with Douglas as first collector for the Royal Horticultural Society. Douglas notes in his journal several times writing to Mr. Menzies on a number of subsequent occasions while at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River.

Taxonomic Confusion

Rhododendron macrophyllum

was given the species epithet for "big leaf in spite of the fact that

R. maximum

had already been given the epithet, suggesting the largest leaf by Linnaeus in 1753.

R. maximum

was quite well known by then in Britain, with its leaves about 25 percent larger in length and width than

R. macrophyllum

.

("Macrophyllum" is pronounced with a soft 'y' "macro-fill-um'' not "macro-file-um." The latter means "a big lot of genera", not "big leaf.)

Hooker named David Douglas' collection of

Rhododendron macrophyllum

"Rhododendron californicum" even though he had Menzies' collections in hand for comparison. Douglas did collect seed and is credited with the introduction of

R. macrophyllum

under the invalid "californicum" species name.

Along with this taxonomic tinkering, the senior Hooker also contributed to the disappearance of Pacific rhododendron in yet another way. This came about indirectly through his son Joseph Dalton Hooker.

Overshadowed by Himalayas

The drowning of

R. macrophyllum

is probably best illustrated by the following scenario: In 1848 the Himalayan rhododendrons which son Joseph discovered and from which he collected seed for Kew Gardens were described and pictured by full-page colour lithographs in an elephant folio sized book prepared by his father Sir William, then director of Kew Gardens. This book did much to develop a keen interest among amateurs and increased the anticipation and generated the demand for these plants for the garden and for hybridizing.

This, remember, was a time before photography and before gardeners knew it would be 10 or 15 years before these plants would produce bloom. As a coffee table book of magnificent size with full colour pictures on every page it held centre stage for the two decades before these magnificent Himalayan rhododendrons bloomed.

How could a rhododendron with small muddy pink flowers akin, at least by description, to the common

R. ponticum

hope to hold its own among these exotic giants from the Himalayas - the luscious clear pink and large flower and leaf size of

R. aukiandii

, now

R. griffithianum

, the mauve pink of

R. hodgsonii

, the clear scarlet of

R. thomsonii

and the blood red of

R. fulgens

and the light cream and substance of

R. campylocarpum

.

R. wightii

alone outdid

R. macrophyllum

in truss size, colour, spotting and even leaf size. You can get an idea of what

R. macrophyllum

was up against by comparing it with the Loderi hybrids which came from

R. griffithianum

- 'Loderi Pink Diamond', 'Loderi King George' and 'Loder's White', etc. No wonder it drifted into a botanical and horticultural backwater for more than 100 years.

Second Discovery

The Pacific rhododendron was rediscovered in a British Columbia backwater in the second decade of the 20th century. Even today that place remains a backwater, what with being at the end of the road and having a name both hard to spell and pronounce - Ucluelet (pronounced "you-clew-let).

South of Ucluelet is a group of small islands named the George Fraser Islands. These offshore rocks honour the Scottish nurseryman who settled in Ucluelet and grew rhododendrons, including

R. macrophyllum

. His role in the development of the only commercially available

R. macrophyllum

hybrid, 'Albert Close', with Joe Gable is amply detailed and explained in Bill Dale's article on George Fraser in the Summer 1990

Journal ARS

.

While Fraser had access to the Puget Sound populations of

R. macrophyllum

, it is also quite possible that he collected seed from an isolated occurrence of it on the nearby mountain on the west side of the Alberni Canal across from the towns of Alberni and Port Alberni. I postulate this occurrence of the Pacific rhododendron from the several deer hunters' reports of seeing large evergreen shrubs like the ones in town gardens on the mountain. They have been 'Cynthia', including the one George Fraser planted beside the Anglican church down the road from Dot and Ken Gibson's garden in Tofino, 'Roseum Elegans' and

R. ponticum

in old Port Alberni gardens which they compared with "in the wild" ones they saw on the mountain sides.

Perhaps, not surprisingly,

Arctostaphylos columbiana

, the hairy manzanita, occurs in the Port Alberni area as does Menzies' other Port Discovery discovery, the Pacific madrone,

Arbutus menziesii

.

In-the-Wild: British Columbia

Before I conclude, I will detail the in-the-wild occurrence and range of

Rhododendron macrophyllum

Besides the aforementioned probable Port Alberni occurrence, there are at least three others on Vancouver Island.

The most northerly is the ecological reserve around Rhododendron Lake, southwest of Parksville. Here

R. macrophyllum

has a unique association with the Alaska or yellow cedar,

Chamaecyparis nootkatensis

. This conifer is another of Menzies' discoveries.

Also not far away are those Pacific rhododendrons in the Nanaimo Lakes area. This occurrence is in a valley between Mt. De Cosmos and Mt. Hooker, named after those botanical Hookers of Kew, Sir William and son, Sir Joseph.

A little farther south on Vancouver Island is another occurrence of

R. macrophyllum

around Weeks Lake beside the road from Shawnigan Lake to Port Renfrew. In Menzies' time it was Port San Juan.

The other and larger populations in British Columbia occur in two places on the mainland, both in the upper reaches of the Skagit River. The first is the valley bottom areas around Ross Lake which is the backup water extending into Canada from the dam that produces some of the city of Seattle's electrical power. This area is only accessible from the Canadian side via the Silver Skagit road from Hope.

The other population of

R. macrophyllum

occurs farther up the Skagit River alongside the Hope-Princeton Highway in Manning Provincial Park. This area has an interpretive display at a roadside turnout at mile 19 from the park's west gate.

Quite a number in the valley bottom at the Ross Lake location occur within Skagit River Provincial Park and near a stand of ponderosa pine. This three-needle pine, native of the dry interior, was introduced into the Skagit by early settlers and is not a valid natural association with

R. macrophyllum

as is the Nootka false cypress at the Parksville site.

In-the-Wild: Washington

The Pacific rhododendron was chosen as the state flower for Washington prior to the turn of the century. It was chosen in spite of its somewhat restricted statewide occurrence on the western slopes of the Cascades and the eastern slopes of the Olympics and Puget Sound.

In the last several decades within this restricted climatic range it has increased in numbers and area due in the main to logging and road building. This population explosion is particularly noticeable in the Port Townsend, Discovery Bay, Hood Canal areas where Menzies first saw it. All those names, incidentally, were given by Vancouver for his colleagues and superiors, some say to ensure a wide market for his journal of the voyage.

The Hood Canal Vancouver named after Admiral Viscount Hood. The origin of the Bay where Menzies first saw the Pacific rhododendron we have already seen was named after the Captain's ship. It was not the first or the last ship named Discovery to ply these Pacific Northwest waters, but that is another story.

In-the-Wild: Oregon

Oregon's populations of Pacific rhododendron are the most extensive in numbers and species variation. They occur along the coast in roadside thickets along Highway 101 and in the Cascades south of Mt. Hood. According to Bob Ross and Dallas Boge, Detroit Lake on the Santiam River east of Salem is the locus for an extensive acreage where Pacific rhododendron is the "dominant brush species" of the cut-over lands. It also occurs in southwest Oregon along the Rogue and Illinois rivers, and in valleys in the northern Siskiyou mountain country. The Menzies connection with Oregon is through the state flower,

Mahonia aquifolium

or Oregon grape. Menzies was the first European to discover it. He collected it first, though, around the future Seattle area. Fourteen years after Menzies' discovery of it, Pursh described and published it along with the rest of Lewis and Clark's collection of Northwest natives. They included many others that Menzies was the first to collect.

|

|

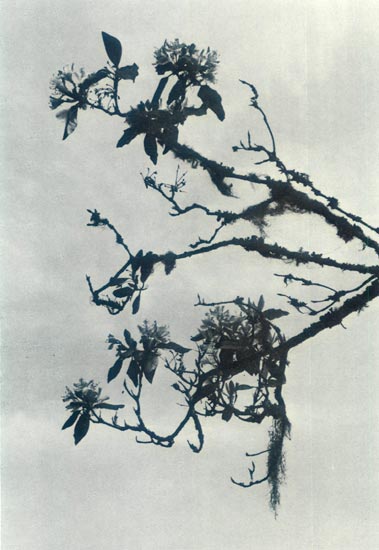

R. macrophyllum

, Vancouver Island, B.C.

Photo by Dallas Boge |

In-the-Wild: California

The Pacific rhododendron extends its range into northern coastal California, joining up with the Coast Redwood,

Sequoia sempervirens

, another of Archibald Menzies' 1787 plant discoveries, and another first. He brought it back to England along with another first, the monkey puzzle tree from Southern Chile,

Auricaria auricana

. With the Coast redwood it was David Don, not Hooker, who buried it into obscurity, classifying it as a swamp cypress and naming it "Taxodium sempervirens". This nomenclatural confusion didn't get straightened out until over half a century later, but that's also another story.

Pacific rhododendron is much more of a woodland, deep shade plant in its California locations than it is anywhere in its more northern habitats. When I first came upon it in a California state park set aside for this rhododendron on Highway 101, it was so shady that I was unable to photograph it with the old Ektacrome 64 film I had in my camera and before I learned you could bump the film times three to ASA 200 to cover such low light woodland situations.

We did find some seedlings on a sunny, silt roadside-cut bank to photograph. Pacific rhododendron may grow, as Cox states, in association with the golden chinquapin,

Castanopsis chrysophylla

, but the occurrence of this member of the chestnut oak family is such a rarity that it is hardly an indicator of the vast majority of

R. macrophyllum

habitat. I personally have never seen them together. The most common tree associated with the Pacific rhododendron is another of Menzies' first discoveries, the Douglas fir,

Pseudotsuga menziesii

.

The Rescuers

The recent developments that are beginning to lift this not-so-big-leaf Pacific Coast rhododendron out of its 200-year obscurity are those activities of members in the Pacific Northwest chapters of the ARS. They have found, photographed, collected seed and seedlings, written articles for the

Journal

and chapter newsletters and have given talks about this Pacific Coast native survivor. People like Frank Mossman, Britt Smith, Dallas Boge, Frank Ross and others see in this species the potential for a wide range of beautiful and persistent drought resistant garden shrubs. I think we owe them a debt of gratitude for looking to those local resources and the beauty that is a part of our landscape heritage we so often ignore for the supposedly more beautiful exotica from afar.

While Menzies may not have thought too much of our Pacific rhododendron, he did think very highly of some of our Puget Sound Georgia Strait seascape-landscapes. On June 6, 1792, he wrote in his journal: "To the Southeast seen through a beautiful inlet, Mt. Rainier augmented by its great elevation and bulky appearance begins the background panorama of rugged and peeked summits covered here and there with patches of snow and running in a due north direction to join Mt. Baker and from thence proceeded in high broken mountains to the northwestward.

"Between us and the above ridge and between the two mountains a fine level country intervened, chiefly covered with pine forests abounding here and there with clear spots of considerable extent. These clear spots, or lawns, are clothed with a rich carpet of verdure and adorned with clumps of trees and a surrounding verge of scattered pines which, with their advantageous situation on the banks of these inland arms of the sea, gave them a beauty and prospect equal to the most admired parks of England.

"A traveler wandering over these unfrequented plains is regaled with a salubrious and vivifying air impregnated with the balsamic fragrance of the surrounding pinery, while his mind is eagerly occupied every moment on new objects and his senses riveted on the enchanting variety of the surrounding scenery where the softer beauties of landscape are harmoniously blended in majestic grandeur with the wild and romantic, to form an interesting and picturesque prospect on every side."

What more could you ask for!

Clive Justice, Director of ARS District 1, landscape architect, park and display garden planner and government advisor, has recently returned from a stint as a volunteer consultant/advisor in Malaysia. Mr. Justice was involved in the redevelopment and restoration of Kuala Lumpur's historic Padang (Independence Square). He is a charter and life member of the Vancouver Rhododendron Society, a chapter of the ARS, and a recipient of the ARS Bronze Medal.