Tips for Beginners: Fertilizing Rhododendrons the Organic Way

Terry Richmond

Port Alberni, British Columbia, Canada

Reprinted from the November 1992 newsletter of the Mt. Arrowsmith Chapter.

When fertilizing rhododendrons we should look to nature to show us the way. In nature mulching and fertilizing is a continuous process with the current year's mulch being gradually transformed in subsequent years to usable fertilizer. Nature's rhodo food begins with a leaf, needle, twig, petal and fruit fall - in short, any and all matter that falls to earth or flows into their area in ground water.

Rhododendrons, because of their environment and the shallow layer of organic matter in which they grow, have evolved a massive root system consisting of literally thousands of tiny, shallow running feeder roots. These roots are extremely efficient in extracting life sustaining plant nutrients from their immediate area. Root systems will be much smaller in a benign climate because a smaller amount of nutrients is required to maintain plant health. Conversely, rhododendrons in exposed and/or harsh conditions will have a vastly increased root system to extract every ounce of nourishment from their surrounding.

|

|

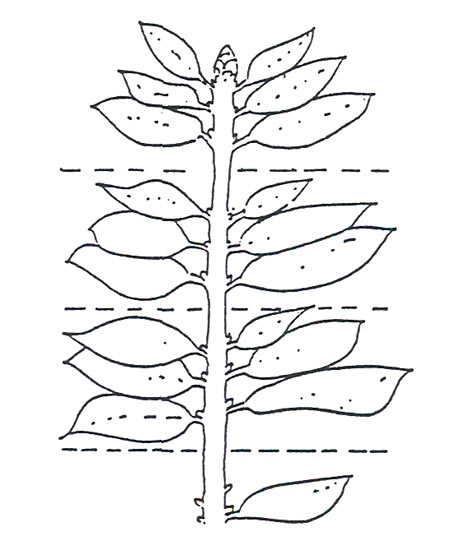

Rhododendrons use old leaves as nutrient storage sites.

As nutrients are used in growth and storage sites are emptied, old leaves fall off. Most will hold leaves into their third flush or third year and on occasion into the fourth. "Read" your rhododendron by identifying the number of flushes of leaves. Three flushes mean the plant is in good condition; two flushes mean the plant is getting hungry; one flush means the plant is very hungry or sick. If leaves are smaller than normal the plants were fertilized late in the season. If the leaves are large, the plant is normal. If the leaves are excessively large and stems are very long too much fertilizer, probably too much nitrogen, was given. (Dave Adams, Oregon State University Extension Service, Corvallis, Oregon.) |

So how do we fertilize rhododendrons in our garden? First, any literature on fertilizing rhododendrons assumes that your plants are growing in the correct medium. Again, as in nature, this medium should be extremely high in organic matter, well drained, well aerated and moderately to slightly acidic. Fir and pine bark, composted oak leaves and evergreen needles, decayed wood, well rotted sawdust, coarse peat moss, reed sedge and topsoil high in organic matter are some of the materials that can be combined in endless combinations to provide excellent growing mediums. Growing medium acidity or pH value is not nearly as critical when growing plants in an organic medium using primarily organic fertilizers. One good quality compost for rhododendrons contains oak leaves, evergreen needles, alfalfa and washed seaweed. Between the various layers an organic nitrogen such as canola meal, fish meal or blood meal can be added.

A word of caution! Rhododendrons, because of their previously mentioned tiny feeder roots, can be easily damaged through over-fertilization, especially when using high analysis chemical fertilizers. Elements to be cautious using include nitrogen, iron, sulfur, boron, sodium and calcium. Contrary to popular belief, rhododendrons do not hate calcium. In actual fact the reverse is true. They will gorge themselves on available calcium until they make themselves sick. With respect to iron, a few years back a respected rhodo grower suggested I supply more iron to help combat the effect of full sunlight in my exposed garden. He was undoubtedly right, but I supplied so much iron sulfate that severe leaf scorching occurred. A little fertilizer goes a long way, especially with small plants.

I fertilize in early spring around the end of March using all the organic fertilizer and soil amendments that I can obtain. When I combine ingredients I try to duplicate natural fertilizer analysis. For instance, in canola meal (6-2-1) and in fish meal (3-2-1) the nitrogen is two to three times that of phosphorous and three to six times that of potassium. Three advantages of organic fertilizers over their chemical counterparts is in their trace element and humic content and in their extended time release of nutrients. Some fertilizers in the following list contain up to 34 trace elements, while seaweed is reported to contain every element presently known.

Blood meal - nitrogen & trace

Bone meal - phosphorus & calcium & trace

Fish meal - complete N-P-K & calcium and trace

Canola meal - complete N-P-K & trace

Cottonseed meal - complete N-P-K & trace

Powdered alfalfa - complete N-P-K & trace

Worm castings - complete N-P-K & trace

Powdered rock phosphate - phosphorus & 32 trace

Green sand - potassium & 34 trace

Kelp meal - potassium & all trace

Dolomite - calcium & magnesium

My base organic fertilizer and filler recipes in volume parts are as follows:

Fertilizer Recipe:

2 parts fish meal

2 parts canola meal

2 parts alfalfa

1 part worm castings

1 part dolomite lime

1/2 part rock phosphate

1/2 part bone meal

1/2 part kelp meal

1/2 part green sand

Filler Recipe:

5 parts sand

5 parts double screened fir bark or

5 parts composted fish waste

The filler, equal in volume to the fertilizer total, is used to prevent clumping of the meal type fertilizers and to minimize the dust problem associated with mixing finely ground or powdered materials.