The Mysterious Red Maximum from Mt. Mitchell

August E. Kehr

Hendersonville, North Carolina

Summary

In the process of building the Blue Ridge Parkway through the mountains of western North Carolina, a small population of wine-red flowered

Rhododendron maximum

was discovered by a road scout. This article gives the history, description, and nature of that unique plant; it also clarifies some of the confusion about the plant, offers five hypotheses to explain the unusual behavior of this rare color mutant, and points out the need for further research.

Introduction

Myths and legends frequently surround the literature of unusual plants. These stories are often a mixture of truths, half-truths, and outright myths. In the genus

Rhododendron

the crimson-red colored

R. maximum

from Mt. Mitchell in western North Carolina has been the subject of at least four articles in publications of the American Rhododendron Society, but none of these tell the complete story, nor do they give the full history of this plant, nor explain the behavior of the red color in any depth.

I have spent at least four years gathering information on this unique plant, writing letters, talking to people, and generally reviewing everything I could learn about the plant and its vagaries. This information is summarized in this article. Despite all these efforts, the full story is yet to be written. The following notes are offered for the purpose of giving an account of all I have learned, pointing out what is still not known, and demonstrating the need for research to complete those yet unknown gaps in our knowledge.

History

In the early days of the 1930s, during the Great Depression, construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway was in full swing as a make-work program. One of the scouts recruited for laying out the route for the Parkway through the wilderness was a Mr. Crayton. Mr. Crayton at one time worked under the direction of George Beadle, the gardener of the Biltmore Estate near Asheville. He was well versed in botany and knew the Latin names of most plants. He kept a diary of places where he found certain plants of interest.

One day in June 1930, according to his diary, he followed an old telephone line through the thickets until he reached a bear trail. The trail led him to a population of 15 to 20 isolated

R. maximum

plants with an unusual flower color. Realizing the importance of his discovery, he collected cuttings. He sent these cuttings to Dr. Tom Wheeldon of Richmond, Va., for propagation purposes. Mr. Crayton also went back to the specific location the following fall to collect seeds of the red-colored plants. Some of this seed was also sent to Tom Wheeldon.

Tom Wheeldon was an avid gardener and president of the Mid-Atlantic Chapter of the American Rhododendron Society for many years. He should especially be remembered in the Society because he was responsible for the first annual meeting of the Society in the East at Winterthur in Delaware in 1962.

Dr. Wheeldon sold or widely exchanged plants of his vegetatively propagated material of the rare red rhododendron to his friends and customers. He was unprepared for the complaints which he received later because all his propagations turned out to be only the common white maximum. Thus he was probably the first to be bewildered and embarrassed by the mysterious, but intriguing red maximum from Mt. Mitchell.

Just how greatly this experience embarrassed and bewildered Tom Wheeldon was related to me by one of his acquaintances as follows: Tom Wheeldon's role in this strange saga was never clear to me. He was close to being psychotic about it, blaming numerous hobbyists for trickery, deception, theft, and collusive conspiracy. It was a monomania with him. For a while he had the idea that Warren Baldsiefen had stolen plants of his red maximum.

The 1957 Expedition

In 1957 a group visited the red maximums on Mt. Mitchell in connection with the installation of the newest chapter of the ARS, the Southeastern Chapter. Joe R. Brooks, first president of the Southeastern Chapter, W. N. Fortescue, a medical doctor and famous rhododendron collector, and Ernest Yelton invited a group of enthusiasts to visit the Asheville area during the blooming season and to attend a meeting of the new chapter, the eleventh chapter of the Society. Members of the party included Joe Gable, Milo Coplen, Lanny Pride, Warren Baldsiefen, Clarence Barbre, Mr. and Mrs. Edmond Amateis, David Leach, Edgar Anderson, and S. D. Coleman. An excellent photograph of most of these persons is found on page 2 of the Jan. 15, 1958 (Vol. 12, No. 1) issue of the

Quarterly Bulletin

of the ARS.

David Leach's account in this issue reads as follows:

Our tour concluded with a trip to a remote mountain to see the red-flowered

R. maximum

about which Eastern fanciers have been hearing for several years. This species has been known heretofore only in white and in shades of pink, and I was especially eager to examine the rarity which we had been promised would be seen later in the week.

As we made our way slowly toward the site, Dr. Ernest Yelton, one of our guides, exhibited his fantastic ability to pass through the all but impenetrable underbrush at a fast gallop, an exhibition of split-second writhing that would blanch the cheek of either an All-American fullback or a fan dancer. But the rhododendron we sought turned out to be strange indeed, so permeated with red pigment that the sap looked like blood. The cambrium of the plant is red, the buds are red, the petioles and leaf veins are red, and the pedicels and flowers are red. Looking at the newly-formed leaves against the light shows a bold red blotch in the center of each. This is a unique rhododendron, possessor of a concentration of pigment hitherto unknown in the genus.

David Leach believes that some of the party collected layers, but no complete record can be located at this writing.

The Second Expedition - 1960

In June 1960 another group made an outing to visit the location found by Mr. Crayton. In the party were W. N. Fortescue, Joe R. Brooks, Joe Gable, the well-known pioneer Eastern rhododendron hybridizer; Henry Yates from West Virginia and a co-worker of Joe Gable; Henry Skinner, director of the National Arboretum and famous for his plant explorations in the Appalachian Mountains; Clement Bowers, author of one of the early American books on rhododendrons; and Nick Fortescue, the son of W. N. Fortescue and the only survivor of the group living at the present writing.

1

Some of this early history came from a talk given by Nick Fortescue at the 35th Anniversary of the Southeastern Chapter on 17 March 1991.

This group found 15 to 20

R. maximum

plants with exciting crimson red flowers, one of the trees being a huge one estimated to be 100 years old. Several of the group collected cuttings and rooted layers, and Nick Fortescue recalls that one plant was dug because he laboriously carried it down the overgrown bear trail: "It weighed 100 pounds and the day was hot."

Records in the National Arboretum showed that Henry Skinner collected material as follows:

Accession No. 15523 - Plant #1, from the largest plant-cuttings.

Accession No. 15524 - Layer of Plant #2, and later propagated as 15524C.

Accession No. 15525 - Plant #3 - cuttings from the best red of the group.

Only material of Accession 15524

2

of Plant #2 survived.

The above information was supplied to me by Sylvester G. March, Chief Horticulturist at the National Arboretum. He made the further remarks: I was Plant Propagator at the time they were received and will not forget Dr. Skinner's excitement and enthusiasm concerning the plants and the collecting experience, when he delivered the material to the greenhouse. In preparing the cuttings, I was fascinated by the deep red pigmentation in the stems of the cuttings. The records show that the material was received on 27 June 1960.

The large plant which was dug and carried out by Nick Fortescue in June 1960 is now known to have gone to Joe Gable of Stewartstown, Pa., where it still lives today. This plant must have flowered several times after 1960, but the flowers were not red; all of them were the common white. They continued to flower white until 1965. These facts are verified by Capt. Dick Steele, now in Nova Scotia. Dick wrote to me on 14 Oct. 1992 as follows: As I remember, probably in 1965, Joe Gable called me to tell me the red maximum finally had a red bloom. I drove up the next day from Virginia Beach (Va.) to Stewartstown (Pa.).

Capt. Steel remembered that he was not highly impressed with the red color, but was anxious to see the plants in the wild. On the spot he and Joe Gable planned to visit the area the next year (see third expedition).

|

|

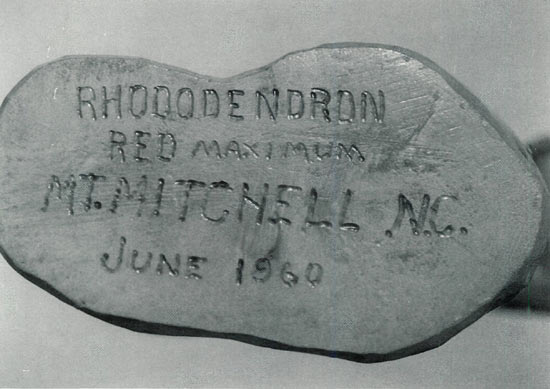

Figure 1. End portion of a gavel made from wood of a

red maximum from Mt. Mitchell, N.C. collected in 1960. |

|

|

|

|

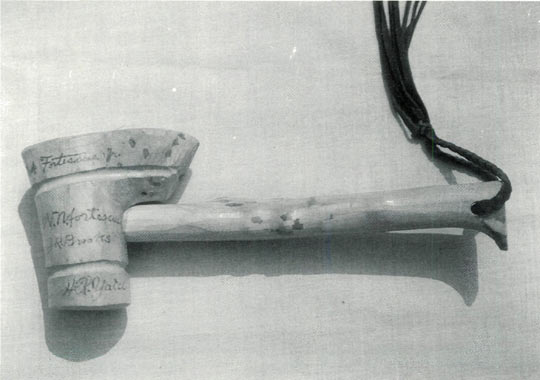

Figure 2. One side of a gavel with autographs

of four members of the 1960 Expedition. |

Figure 3. The other side of a gavel with autographs

of three members of the 1960 Expedition. |

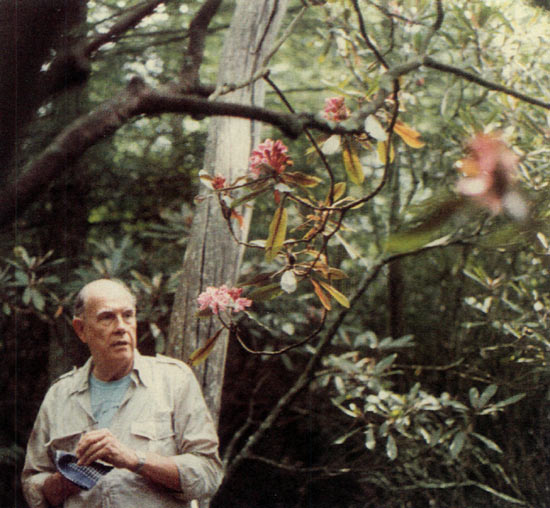

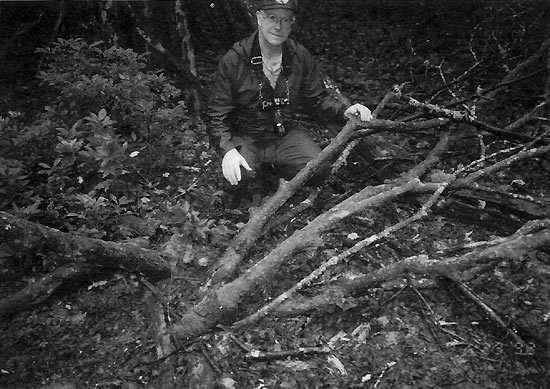

It is possible that some of the other collections made on the 1960 trip survived, but I have no record of them. There are historical mementos existing of the 1960 trip. Henry Yates took wood of the original tree and made it up into gavels for seven members of the expedition (see Figs. 1, 2 and 3). On each gavel he burnished into the wood the autographs of each member and the date of the expedition. As I write I hold one of these gavels which is owned by Mrs. Henry Skinner. No one seems to know at the present writing what happened to the other six gavels. These gavels have historic value because the original 100-year-old tree existed in July 1992 only as a huge skeleton of multiple trunks and branches sprawled out over the forest floor in a circle about 40 feet in circumference. Some of the individual trunks are 5 to 6 inches in diameter (see Figs. 4 and 5).

|

|

Figure 4. John Barber, Asheville physician, and one

branch of the original tree of red maximum about 1983. Photo by Harold Crutcher |

|

|

Figure 5. Ed Collins with a portion of what is believed to be the

original tree of red maximum. The tree was dead in 1992 and the skeletal remains covered a circle about 35-40 feet in diameter. |

An amusing anecdote of this trip is told by Mrs. Henry Skinner. The men had to crawl under dense underbrush (through a bear trail according to Nick Fortescue) to get to the red maximum. Clement Bowers had on a white nylon shirt which was totally black when he got back to Asheville. Even in 1992 the underbrush was still thick, but no longer did the bear trail exist, although bears still roamed in the area.

The Third Expedition -1966

For most of the information on the third expedition to Mt. Mitchell in 1966 I am indebted to Caroline Gable and Dick Steele. Dick Steele wrote me a letter on 14 July 1967 from SACLANT Headquarters in Norfolk, Va., in which he reported on his visit to Mt. Mitchell the previous year as follows: In regards to the red maximum, I should have paid more attention to the circumstances surrounding this plant but here are some of the things I noted.

It appeared that the red infusion of the leaves and part of the stem was in the previous year's growth, and to some extent in the year's growth prior to that; the current year's growth appeared to be developing along the same lines. In all growth prior to this, there seemed to be little indication of the redness, the leaves were quite normal looking, the only specific indication of redness was in the heartwood of the 3- or 4-year-old section of the branch.

In the areas that showed pronounced redness, the bark was thicker and rougher, sort of somewhat swollen and rugose in texture, and it seemed to have a much more pithy growth than the normal maximum. The leaves have quite a different shape in most cases than the normal maximum, being shorter and more broadly blunt.

I did not rule out entirely that this might be some type of a virus; however, I know nothing about the effects of viruses or other such invaders.

There were a couple of other interesting observations while I wandered through the very thick thicket in which these plants grow. There were five plants which showed specific red indications and these were spread over quite an area. There was not any evidence that they would be layers of a single plant which had crept out over the years.

The surrounding pink or white maximums also had the shorter, blunter, broader leaves to some extent, and there were other character similarities between them. I noticed at least one catawbiense

3

specimen growing in this thicket area of the maximum, and there may be more. This particular catawbiense had a tendency towards redness that the maximum shows; however, I felt that the coloring of this plant may have been caused by the shade in which it was growing.

I have not ruled out of my mind entirely that this particular group of plants may be some type of natural hybrid with catawbiense in which maximum has been re-injected for a number of generations back into the blood. However, except for the different blunter and broader shapes to the leaves and the color, there are no other indications of catawbiense; the truss is typical maximum.

Dick Steele brought back a red flowered truss for his daughter to paint. He then grafted it on 'County of York'* root-stock. He still has that plant as of this writing. It has always flowered red only. Seedlings of this plant also have been red. It must be concluded that there were some plants in the population on Mt. Mitchell even in 1966 that were true-breeding (homozygous) for red color. (See later the reference to 'Mount Mitchell' RSF 77/646.)

A letter from Caroline Gable date 2 August 1992 also gives information on the red maximum: So you are tackling the Great Red Max Mystery. I am delighted, hence this prompt response.

A number of years ago someone encouraged me to write on this subject for the ARS Journal. I brashly assumed I could interview a couple of people, add my scant first-hand knowledge, and ask the readers if they could contribute. It wasn't that easy.

I did call Dr. Fortescue Sr. and talked to him at some length. Two things he told me stick in my mind. One was that, contrary to my impressions, some members of the '60 (your date; I have nothing to go by) trip went home with rooted layers. My father received the only plant taken at that time, Dr. Fortescue said. This certainly sounds like the big plant that Nick Jr. remembers having to tote out.

As you remembered, the first blooms here were whitish. There was some conjecture about soil differences. In a few years mid '60s maybe, at least while Dad could still see color the red blossoms appeared on one section of the plant. That has continued.

Henry Yates grew seedlings and gave away small potted plants at an ARS convention before he died about 1970/71. I assume the seed was from here. I have a head-high plant I grew from a red-truss cutting. It first bloomed white a couple of years ago, and is now showing some red veining in the leaves (see Fig. 6).

|

|

Figure 6. Red colored portion from a plant

of red maximum 'Mt.Mitchell' RSF75/137. |

I think I can account for the Species Foundation record "from the Gable farm." When the Foundation was starting up, I gathered a few cuttings here and sent them out. I remember including some Red Max and labeled it "Mt. Mitchell."

There is an intermediate shade between the red and white flowers, a pleasant pink (see Fig. 7). It is possible, even usual, to have all three shades on the old plant at the same time. The plant is about 15 feet high now and almost as wide at the top. It is single trunked and upright, no layering. The leaves are smaller than normal for maximums.

|

|

Figure 7. Pink flowered seedling from seed of

red maximum 'Mt. Mitchell' RSF 75/137 Photo by George Ring |

Along the same line as the above, I once thought I would be very smart in propagating the red maximum, so I took a solid red scion from the Gable plant about 1968 and grafted it on maximum rootstock. I foolishly reasoned that the red scion would continue to flower red. To my utter surprise the red scion finally grew into a plant that flowered white. At the point that I was ready to discard it, it unexpectedly developed a red-flowering branch. My first introduction to the red maximum was therefore a lesson in humility.

The Red Maximum in the Rhododendron Species Foundation

The Rhododendron Species Foundation has in its inventory two forms of red maximum, both distinct clones, but with very confusing names as follows: 75/137 from Caroline Gable called 'Mt. Mitchell'. 77/646 from David Leach called 'Mount Mitchell'.

The material from Caroline Gable (75/137) was taken from the tree carried out in 1960 by Nick Fortescue. Thus this accession at the RSF is a direct line propagule from the original plant collected on Mr. Mitchell. As described by Caroline Gable, this plant can eventually have three types of flowers on the same plant white, pink, and red simultaneously, and occasionally picotee and blotched.

On the other hand, RSF 77/646 has a quite different origin. According to Dave Leach, in his letter to me dated 16 Sept. 1991, RSF 77/646 was derived from seeds from the Gable plant. Dave Leach recalls that Warren Baldsiefen grew out a large population of seedlings from the Gable plant (syn. RSF 75/137) and selected a single clone that was red-flowered and which is now identified as 'Mount Mitchell' RSF 77/646. Persons obtaining plants from the RSF should be aware of the vast difference between these two accessions with quite similar names.

A color photograph of red maximum taken by David Leach is shown on the cover of the ARS

Quarterly Bulletin

, Vol. 19, No. 2, April 15, 1965. The color rendition is not good, because the actual color of the truss is much more carmine red than is illustrated.

Breeding Behavior of the Two Clones

The relative scarcity of plants of the two clones precludes a large amount of information on their breeding behavior. Furthermore, one must identify accurately the history of his plants to trace them to vegetative propagules of either 'Mt. Mitchell' RSF 75/137 or 'Mount Mitchell' RSF 77/646.

| Table I | |

| Color of Flowers | Probable or Actual Breeding Behavior |

| White | Behaves as white recessive |

| Pink | Behaves as pink recessive but will segregate when selfed |

| Red-clone 'Mount Mitchell' | Behaves as dominant red |

| Red-clone 'Mt. Mitchell' | Segregates for red, white, pink, picotee, bicolor |

| Picotee and Bicolor | Has not been widely tested but see 'Ruddy Red' |

BREEDING BEHAVIOR OF 'MT. MITCHELL'(RSF 75/137)

The original tree as collected on Mt. Mitchell in North Carolina, and its direct vegetative derivatives, produces a wide array of flower colors, such as white, red, pink, picotees, and bicolors. Thus the breeding behavior is dependent upon which color of florets is used. The breeding behavior of these types of floret color has not been fully tested to my knowledge, but Table I shows a best-guess guide.

George Ring has grown out and flowered seedlings from the red sectors of 'Mt. Mitchell'. From these seedlings he found only two that were red in the bud and opened picotee over every truss on the plant. All the rest (15 to 20 plants) were pink.

Red maximums are (and have been) used in several breeding programs. These are described as follows:

Mr. Clark Adams of Butler, Pa., grew four generations of 'Mt. Mitchell (RSF 75/137) and selected a clone which he named 'Ruddy Red'*. 'Ruddy Red' has a red blotch with white edges. From Mr. Adam's description given to me over the telephone it perhaps resembles somewhat the flower in Fig. 9. He has crossed 'Ruddy Red' with 'Midsummer' and says the hybrids are exceedingly beautiful.

On the other hand, Weldon Delp registered an F4 plant of Gable's red flowered maximum ('Mt. Mitchell' RSF 75/ 137) as 'Delp's Red Max' in the ARS Journal, Winter 1993, Vol. 47, No. 1. He describes the color as purplish red (60C-D) shading to pale purplish pink 62D, deep red outside the petals (60A), hence it is probably much like 'Mount Mitchell' (RSF 77/646) in appearance.

George Ring kindly supplied information on the use of red maximums in the 1993 ARS Seed Exchange list as shown in Table II.

| Table II | |

| #238 | maximum ('Ruddy Red') selfed - Tom Ring |

| #241 | maximum ('Mt. Mitchell') selfed - Robert Gamlin |

| #1031 | maximum ('Ruddy Red') #1 [( maximum Childers x 'Anna Delp' #5)] - Tom Ring |

| #1032 | maximum ('Ruddy Red') #1 x 'Mandalay' - Tom Ring |

| #1034 | maximum ('Mt. Mitchell' Form "rose truss" x ( yakushimanum x rex) - Russ Gilkey |

| #1035 | maximum ('Mt. Mitchell' Form pink and white truss) x (Sappho x Calsap) #1 - Russ Gilkey |

Many years ago, Warren Baldsiefen grew seed from 'Mt. Mitchell' RSF 75/137 and selected a segregate that was pure breeding for red, and later became 'Mount Mitchell' RSF 77/646.

I am growing a large population of seedlings of the one red-flowered clone found in 1992 growing on Mt. Mitchell. Even in the seedling stage I can detect seedlings that have pigmentation in their stems and leaves. It is probable that this individual clone yet growing on Mr. Mitchell acts like the red color of Dave Leach's 'Mount Mitchell'.

The above-mentioned red flowered clone was flowering in July 1992 when a group of five members of the Southeastern Chapter visited the area.

4

The visit was made on 23 July 1992, at which date the flowering season was almost over. Thus we found only one plant with a truss of red flowers, and most of that truss had already flowered and dropped (see Fig. 8). A close examination of the leaves and stems of this sole late bloomer indicated it was red in all parts similar to the red-flowered branches that spring periodically from plants of 'Mt. Mitchell'. The conclusion seemed to be that this was a red seedling from one of the original plants. Judging from the above described seedlings, I would say it was true breeding for red. In genetic terms it is homozygous for dominant red genes, as in RSF 77/646.

|

|

Figure 8. Truss of the white flowered form of R. maximum

and a portion of a truss of the wine red form, July 23, 1992. |

BREEDING BEHAVIOR OF 'MOUNT MITCHELL' (RSF 77/646)

The only experience of the breeding behavior of 'Mount Mitchell' is that of David Leach, probably because he has the only flowering plant of this clone outside of the RSF. Dave Leach in his letter of 16 Sept. 1991 is quoted as follows: There is quite a difference between these two (clones). One ('Mount Mitchell') has red sap and the tissues are impregnated with the red pigment; this is conspicuous in the spring and diminished as the season advances. This form has flowers which are redder, and more extensively so. This is the clone I sent to the Rhododendron Species Foundation, as I recall. The flowers are consistently red, and yield red progenies when crossed with white.

We can safely conclude therefore that 'Mount Mitchell' is true breeding for red, or in genetic terms, is homozygous for dominant red genes. It should predominate for red progeny when used in hybridization, and as such should be a highly valuable parent for hardy red hybrids. It should be mentioned that

R. maximum

transmits large healthy roots to its offspring.

The Cause of Color Instability

The cause of the unstable red color is central to this article. Lacking concrete evidence from research studies, all that I can do is to discuss five possible hypotheses, and offer my personal opinion on the probability of each hypothesis being the correct one.

HYPOTHESIS #1 - IT IS A HYBRID

The red maximum occurs in a very localized area in North Carolina, and has not been found anywhere else. The predominant rhododendron species in that location is a white flowered

R. maximum

. The only other non-scaly species native to that part of North Carolina is

R. catawbiense

.

Hybrids between

R. maximum

and

R. catawbiense

have been made by hybridizers, and the resultant plants are uniformly light lavender without a hint of red coloration. In the wild

R. maximum

does not readily hybridize with

R. catawbiense

for two reasons. First

R. maximum

is notorious for its proclivity to self pollinate in the unopened buds. In fact, in hybridizing this species using it as a seed or female parent, one must remove the anthers at a very young stage of the bud because the pollen is mature and functional many days before the flower buds open. It is probably safe to say that most of the seed produced on this species comes from self-pollinated flowers.

Secondly, in North Carolina the species

R. maximum

and

R. catawbiense

are isolated geographically and in time of flowering.

Rhododendron maximum

grows at low elevations while

R. catawbiense

grows at much higher elevations. It is seldom they are found growing in close proximity to each other. Likewise the season of flowering seldom overlaps;

R. catawbiense

usually flowers 2 to 3 weeks or more before

R. maximum

.

In actuality the author knows of no documented cases of natural hybrids between the two species in North Carolina. Some might argue that hybrids of

R. maximum

with some of the native deciduous azaleas, especially the red

R. bakeri

, could give red hybrids, but such hybrids are not known to occur naturally or otherwise to my knowledge.

David Leach told me that many years ago he received a plant from La Bar's Rhododendron Nursery which appeared to be an advanced generation natural hybrid of

R. maximum

and

R. catawbiense

. He called it 'Maxcat'.* A similar hybrid was developed by Joe Gable under the name 'Maxecat'*.

In summary, the facts available indicate, with "99 44/100%" certainty, that the wine red color is

not

of hybrid origin.

HYPOTHESIS #2 - EFFECT OF UNKNOWN PLANT PATHOGENS

In his letter of 14 July 1967, Dick Steele indicated he could not rule out the causative agent of the red color as some type of virus. This hypothesis is also favored by others, including Dr. Ernest H. Yelton who was the leader of the 1957 expedition to Mt. Mitchell.

One virus is known to invade certain cultivars of rhododendrons, especially those which are progenies of

R. campylocarpum

and

R. griffithianum

. Reports have come from the Pacific Northwest and Germany (2). The symptoms of the virus are circular rings on the older leaves, usually with a reddish color in the center of the rings. The flower color, however, is not altered as compared to healthy plants.

Although this hypothesis cannot be ruled out considering our limited knowledge at present of the nature of the red color, it is the author's best guess that the cause is not from plant pathogens.

HYPOTHESIS #3 - PHYSIOLOGICAL ORIGINS

It is known that physiological or environmental conditions affect red color in other plants. For example, Marousky found in 1968 that the lower the temperature during the growth of

Poinsettia

the greater the concentration of the red pigments pelagonidin and cyanidin glycosides in the bracts (8). Thus the lower temperature resulted in poinsettias with deeper red coloration. It is pertinent, however, to point out that even when grown at high or at low temperatures, red poinsettias are still red, and only the intensity of the red color is affected - not the red color itself.

Other environmentally caused changes in color run the gamut of fertilizer concentration, soil acidity, intensity of sunlight, soil moisture and others. However, in all such conditions the color itself was basic and a function of the genetic make-up of the plant. Perhaps the greatest effect of color is that of soil acidity on hydrangeas where pink can be changed to blue by changing the acidity. A change from white to red has never been demonstrated in rhododendrons as a result of environmental factors.

The author had many friendly discussions with Henry Skinner about whether the red color in the red maximums could be environmentally caused. In fact, Dr. Skinner sent a plant of 'Mt. Mitchell' (U.S. National Arboretum Accession 15524C) to Polly Hill in 1972 to test the environmental effect of a cool climate on the ultimate color. It was proven that the environment on Martha's Vineyard did not alter the color expression. The plant on that cool island behaved exactly as it has done in all locations where it has been grown from Martha's Vineyard to Maryland, to Virginia, to North Carolina. Polly Hill did photograph some pretty red blotched flowers that appeared on her propagule of 'Mt. Mitchell' (Fig. 9).

In my opinion a physiological basis for the red color is unproved and unlikely.

|

|

Figure 9. Normal white form of the original clone

of 'Mt. Mitchell' and a partially red truss. Photo by Polly Hill |

HYPOTHESIS #4 - MOVABLE GENES

In the early 1950s Dr. Barbara McClintock, working on corn (maize) plants, began to call attention to the novel behavior of corn plants, which she later proved was caused by movable genes. She started this work at Cornell University, and I can recall seeing her at work in the field where she made her corn crosses, as well as in the botany laboratory where she was my laboratory instructor. It is to our discredit that we as students sometimes facetiously said she was working on "jumping genes." She later won the Nobel Prize for this work.

These movable genes did not have fixed locations on the corn chromosomes. Instead they moved about unpredictably among the various locations on the chromosomes. As they fixed themselves at a given location, they inhibited the expression of the corn genes with which they came into close proximity. Thus they moved about somewhat at will, altering the genetic expression of the nearby genes, seemingly causing gene mutations. Furthermore, when the movable gene moved to another location, the nearby gene returned to its former and original genetic action. Hence the movable genes caused instability and supposedly high rates of gene mutations.

The instability of the red color in the clone 'Mt. Mitchell' is suggestive of these movable genes. Many members of the American Rhododendron Society, especially those who grow certain cultivars of evergreen azaleas, have been mystified by the instability of colors in a few azalea cultivars. Some cultivars of the Glenn Dale azaleas in particular have striping, spotting, and speckling of colors. Likewise, many of the Japanese cultivars have this same apparent instability in the colors of flowers.

The mutations caused by movable genes are unstable and are characterized by segments, striped and flecking in a wide profusion of patterns. Propagators of evergreen azaleas are especially familiar with these "sports," as they are called, and must continually select propagating wood with great care in order to preserve the so-called true type for the particular cultivar.

There is no research evidence to rule out movable genes as an explanation for the haphazard appearing and disappearing of the mutants in 'Mt. Mitchell'. However, the extreme forms of flecking, spotting, striping and sectoring do not show up in 'Mt. Mitchell' or its seedling progeny as they do in corn. The present evidence almost certainly rules out movable genes as a cause of the instability of flower colors in 'Mt. Mitchell', and I am quite comfortable in saying such movable genes are not present in the red maximums.

HYPOTHESIS #5 - SOME KIND OF CHIMERA

In the

Dictionary of Genetics

by R. L. Knight there are 17 kinds of chimeras defined, most of which apply to flowering plants (5). A plant chimera is a plant composed of two or more genetically distinct types of tissues. Some of the more common types known in horticulture are graft hybrids, sectorial chimera, mericlinial chimera and periclinal chimera. In animals an extreme kind of chimera is found in fruit flies in which one side of the fly is female and the other half is male. One of the most interesting chimeras that I once grew, but lost in a very cold winter, was a graft chimera in a camellia. This particular chimera resulted from a fusion of tissues of a named cultivar of

Camellia japonica

grafted on rootstock of

C. sasanqua

. An adventitious bud developed from a mixture of tissues at the graft union. From this adventitious bud came plants that sprouted three kinds of growth in an unpredictable manner. The result was a plant sporting the original cultivar, the sasanqua, and a new unusual mixture of the two with a distinctive flower of its own. Thus the plant had three distinct types of leaves, flowers and twigs that appeared and disappeared willy-nilly in an unpredictable manner on the same plant. If any reader still has this plant I would like to find it again. It was an interesting conversation piece and a plant that had to be seen to be believed.

Some of my co-workers in the U.S. Department of Agriculture studied in great detail periclinal chimeras in many plants (9). They concluded that the growing point of a plant with a periclinal chimera developed three distinct layers of cells called Layer 1, Layer 2, and Layer 3. As the plant grew, Layer 1 and Layer 2 tended to remain as the outside layers of cells and covering Layer 3.

The larger part of the initial growing point was Layer 3, which predominated the bulk of the early growing point. However, as growth continued, Layer 2 sometimes replaced Layer 3 in the outer growing regions, leaving Layer 3 totally or partially behind. The result was that in subsequent growth the growing tips would be Layer 2, but could also be a combinations of cells from Layer 2 and Layer 3. When Layer 2 and Layer 3 had different genetic characters (genes), one could observe these differences in the growing plant as variegations.

In the red maximum ('Mt. Mitchell' RSF 75/137), these outer layers (L-1 and L-2) could be:

The original "white" tissue, in which case the flowers and leaves would be like the original white maximums, or

From the mutant red tissue, in which case the flowers and leaves would show the red pigmentation, or

A mixture of the original white tissue and the red mutant tissue in which the flowers would be a bright pink, picoteed, blotched, or red.

I recently cut a series of cross-sections from my plant of 'Mt. Mitchell' and found there were segments of the stem in which some were red, some were white, and some had segments of each color. These colors changed as one progressed along the stem cutting cross-sections, although the predominant color was white in the material I was cross-sectioning. The important point was that the stem I was sectioning was a kind of mosaic of tissues in which the colors changed unpredictably as I progressed along the stem.

All the above observations might support the hypothesis that the red maximums are chimeras, and most probably a periclinal chimera. It will require a serious research investigation to make such a determination with some assurance.

A copy of the manuscript of this paper was submitted to Robert N. Stewart whose work is cited above. His comments were: "Your observations are in no way consistent with chimeras. The color of petals is almost exclusively in the epidermis and usually are different in chemistry and expression from that in the stem and leaves. I don't think there is evidence to really explain the observations."

SUMMARY OF THE HYPOTHESES

At this writing there appears to be no one hypothesis that may satisfactorily explain the unusual behavior of the color patterns in the mysterious red maximum from Mt. Mitchell. This mystery can only be resolved by some future research, perhaps sponsored by the ARS Research Foundation. In the words of George Bernard Shaw, this article "stirs up the fog, but doesn't lift it."

However, if the author were to be forced to select the most likely hypothesis, it would be the chimera hypothesis, with the reasoning that somehow I did not make the facts clear to the reviewers in the U.S.D.A.

Basic questions still remain, namely where and how did the red mutant arise, and could it be reproduced experimentally? Mutations are rare in

R. maximum

, seldom found in the extremely wide distribution along the eastern seaboard of North America following the Appalachian Mountain Range from Canada to Georgia in the U.S. The Appalachians are some of the oldest mountains in the world and can anyone doubt that the species

R. maximum

may also be equally old? Despite this, variants are few, but distinctive. I have a mutant that few experts identify at first glance to be a form of

R. maximum

. Even a bright yellow flowered mutant may have occurred (1, 4).

Rhododendron maximum

with its fine horticultural attributes and genetic characteristics is a much underrated plant.

Addenda

I have just received a report of another location where one mature plant of red-flowered

R. maximum

is growing, though this plant is in a declining condition. It was reported by Mr. Wayne Packard, State of North Carolina Plant Inspector, who lives at Bryson City, N.C. This plant is located in Clay County, N.C. near the Cherokee County line, N.C. at Brasstown, N.C. It is growing in heavy clay soil, and was described as having the same crimson red flowers as the plants growing on Mt. Mitchell, N.C. Mr. Packard examined my plant of Mt. Mitchell 75/137 and believes the appearance of this new plant is similar, except that new leaves may have a more frosted appearance on the upper surface.

November 1993

Two new facts have just surfaced, thanks to Plant Name Registrar Jay Murray. First, the name 'Mt. Mitchell' is attributed to Joe Gable in the 1958 International Register of rhododendron names two years before he received the 1960 plant now known as 'Mt. Michell' 75-137. Second, on page 34 of

Hybrids and Hybridizers

, edited by Livingston and West, is a reference to a layer of a

maximum

hybrid or variety collected in the wild in North Carolina in 1930. Hence, two different clones existed in the Gable garden. It is evident that Joe Gable received from someone a layer from the 1930 collection made by Mr. Crayton on Mt. Mitchell, N.C; the fate of this plant is presently unknown. However, Caroline Gable believes that 'Mt. Mitchell' 75/137 in the RSF botanic garden is from the 1960 collection.

December 1993 References

1. Brooks, M. The Appalachians. Houghton Mifflin Co., 1965:1-331 (see especially 242-244).

2. Coyier, D. L. Disease control of rhododendron. In: Luteyn, J. L.; O'Brien, M. E., eds. New York Bot. Garden. Contributions toward a classification of rhododendrons. Lawrence, KS: Allen Press; 1980:289-304.

3. Hill, P. The deep red

Rhododendron maximum

at Barnard's Inn Farm. Jour. ARS 43(1):6-7; 1989.

4. Kehr, A. E. Come and see us in the Bonnie Blue Ridge Mountains in 1994. Jour. ARS 47 (4): 203-205; 1993.

5. Knight, R. L. Dictionary of genetics. Chronica Botanica Company, 1948: 1-167.

6. Leach, D. L. A new look at the azaleas and rhododendrons of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Quart. Bull. ARS 12 (1):2-7; 1958.

7. Leach, D. L. The rosebay rhododendron: historical oddities, unusual forms, its value as a parent. Quart. Bull. ARS 19(2):66-74; 1965.

8. Marousky, F. J. Effects of temperature on the anthocyanin content and color of poinsettia bracts. Proc. ASHS 92:678; 1965.

9. Stewart, R. N.; Dermen, H. Flexibility of ontogeny as shown by the contribution of shoot apical layers to leaves of periclinal chimeras. Amer. Jour, of Botany 63 (9): 935-947; 1975.

1

It is possible Mrs. Yates was along, but this cannot be confirmed.

2

National Arboretum Accession 15524 is probably synonymous with 'Mt. Mitchell' RSF 75/137, at least in breeding behavior.

3

Catawbiense plants are still growing in the area in 1993.

4

Ed Collins, Nick Fortescue, Ray Head, Dr. Dan Veazey and August Kehr. In 1993 a group visited the area on 8 July, and found that all plants were finished flowering.

Editor's Notes:

* Unregistered but not in conflict with a registered name.

** 'County of York' is a synonym for 'Catalode'.

Dr. Kehr, a member of the Southeastern Chapter, is a frequent contributor to the Journal and a recipient of the ARS Gold Medal Award.