The Victorian Rhododendron Story

Clive L. Justice

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada

Sir William Jackson Hooker, one of England's greatest nineteenth century botanists who rescued Kew Gardens from oblivion after the death of Sir Joseph Banks

1

, was reputed to have said: "Perhaps with the exception of the rose, the queen of flowers, no plants have excited more interest throughout Europe than the several species of the genus

Rhododendron

." He is said to have made this quiet statement when he introduced the magnificent elephant folio of full coloured lithographed drawings of the 26 species of rhododendrons his son, Joseph Dalton, had found and collected in the tiny kingdom of Sikkim, between Nepal and Bhutan in the eastern Himalayan mountains. The father had edited this "spectacular" in botanical art. The lithographs were by Walter Fitch from J. D.'s on-the-spot sketches. They were unusual in that they were not only great works of botanical art but they were also, as time would tell, an understatement of the magnificence of the real plant they pictured.

2

This was unusual in a way that it gave, at least for those rhododendron species that Hooker

fils

had brought back, a very special status and a "leg up," so to speak, into the realm of the aristocrats of plants.

Rhododendrons of the Sikkim Himalayas

was a "coffee table book" picturing majestic exotics with pure blood-red and glistening white flowers with 6-inch-long trumpets and 4-inch-diameter faces, each in a cluster of eight. That was not all, as many had leaves 12 to 18 inches long and half as wide.

3

These depictions, made in an era prior to photography, placed them squarely into a class of exotic plants above and beyond the earlier drab and delicate foliage and flowers of the rhododendron and azalea representatives that had come into British gardens, woodlands, and landscapes from North America and Asia Minor over the hundred years prior to 1850 and Hooker's 26 Himalayans.

In the run up to the age of Victoria (she came to the throne in 1837), the last half of the eighteenth century and first two decades of the nineteenth in the British Isles is usually characterized as the "the age of enlightenment." For landowners, gardeners, and foresters this period was the "age of improvement." There were improvements to agriculture enriching soils by liming and manuring, and books on the subject

4

, improved vegetable, flower, and field crops, and renewed interest in planting of forest with the management of woodlands that included an under storey of exotics. Among these exotics were the newly arriving woodland plants from North America, including rhododendrons and azaleas. This interest in woodland activity was partly a result of the reprinting of the seventeenth century classic on forestry, John Evelyn's

Sylva

, which advocated tree planting for cropping and for the ornamentation of grounds.

Perhaps one of the greatest of all the eighteenth century improvements to land and plants came in ornamental horticulture and landscape gardening. In the latter, improvers like William Kent and "Capability" Brown and, last but not least of the great, Humphry Repton, were influenced by the essayist Joseph Addison and the poet Alexander Pope, "who prepared the new art of gardening [on] the firm basis of philosophical principles."

5

Pope in his

Epistle to Lord Burlington

set forth the principles of the arts as: the study of Nature, the genius of the place, and the use of good common sense. The Rev. Dr. Alison, author of the

Essay on the Nature and Principles of Taste

,

6

observed that our [English] taste for natural beauty was awakened by the power of simple nature. It was felt and acknowledged in the natural expression of scenery. We must therefore cultivate this taste by the study of the means by which it might be maintained and improved.

As these efforts to create landscape gardens developed through the last half of the eighteenth century with the work of the improvers gardeners began to incorporate in their layouts and plantings the new exotic trees like

Liriodendron

and evergreen

Magnolia

, along with shrubs from the mountains and deciduous forests of America. Peter Collinson, a London merchant and garden enthusiast, persuaded a fellow Quaker and farmer, John Bartram of Philadelphia, Penn., then of the thirteen British colonies, to collect and send him seeds and plants for himself and various patrons including Lord Petre, the dukes of Richmond, Norfolk and Bedford, Philip Miller

7

and others.

In the 1760s, among the shrubs and trees Collinson and his patrons grew on from Bartram collections in the Allegheny and Appalachian mountains were two rhododendrons,

Rhododendron maximum

and

R. periclymenoides

(formerly

R. nudiflorum

), the broad leaf evergreen rosebay and the deciduous pinxterbloom azalea. Both these large shrubs, along with other American shrubs that are rhodo leaf look-alikes (

Kalmia

, or sheep-laurel,

Pieris

, or Andromeda, and the American laurel-leaved holly), were naturalized into the woodland areas of a number of the late eighteenth century landscape gardens. Grown in areas of peaty, hence acid soils, these plantings came to be known as American gardens.

8

In the last decades of the eighteenth and the first two decades of the nineteenth century many landscape gardens took up on the woodland garden with American plants adding the new North American plant discoveries that were introduced by John Fraser, Andre Michaux and son Francois, collecting in Eastern United States with Thomas Nuttall and David Douglas collecting in Western North America. The mauve flowered catawba rhododendron from the mid and southern Appalachians of Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia with several azaleas from the same mountains along with the Western azalea

9

and David Douglas' pines, firs, and spruce trees from the Far West joined

Rhododendron ponticum

from Asia Minor via southern Spain. It had already become well established in the woodland landscapes of Southern England

10

with its mauve flowers and lush dark green foliage.

Two rhododendrons that did not quite fit into the woodland natural landscape garden made an appearance from the Caucasus mountains.

Rhododendron caucasicum

was a low alpine, full-sun plant with cream, yellow to pink flowers coming to Kew Gardens in 1803. The other rhododendron was from India, the tree rhododendron

R. arboreum

, far too tender for all but the most sheltered English gardens. When it first bloomed in 1825, 30 years after it had been first introduced, it created a minor sensation. Despite its tenderness and 30-year age before blooming, it had one great feature all the other rhododendrons then in cultivation lacked, the colour of its flowers. They were a deep dark red. Here at last was the potential when crossed with the very hardy and comely shrub rhododendrons from America, in particular the catawba,

R. catawbiense

, to create red and near red flowered evergreen shrub rhododendrons that would be hardy and so salable throughout the British Isles.

Between 1820, when the first hybrid rhododendron was developed in the Mile End Road plant nursery area on the outskirts of London, and 1860 there were more than 500 different hybrid varieties named and introduced.

11

These plants when they bloomed had many tight balls or heads of flowers atop an all-around collar of shiny green leaves.

12

The possibility existed to produce a rich variety of colours, enough to satisfy the most colour conscious new Victorian landowner. Fredrick Street wrote: "[I]t was profitable [now] to go to all the trouble of raising so many new varieties, propagating them, and putting them on the market. A new class was growing up out of the industrial revolution. Manufacturers, bankers, financiers were making money and moving out of London to country villas and small estates...[T]here was one way in which it was possible for the

nouveau riche

manufacturer to rub shoulders with the landed proprietor - [it was] through gardening...gardening became the status symbol of the industrial revolution."

13

These gardeners, the new "improvers," became collectors of each new rhododendron hybrid and other new plant novelties that became available. They were advised by the writings of J. C. Loudon, particularly in his book

The Suburban Garden and Villa Companion

, to display plants separately in a scattered fashion along pathways that wound through a stretch of grass in front of the vine covered house.

14

As each shrub or tree was to be examined closely they must be perfectly grown and be rare, exotic looking, and suitable for the new taste in pleasure gardens as well compete for attention with the colourful exotic orchids, camellias, and other tropical plants being grown in conservatories and greenhouse heated by the modern fuel, coal. The new hybrid rhododendrons fitted the bill perfectly. Henry Phillips, a contemporary of Loudon, addresses the rhododendron specifically: "The most beautiful shrubs should occupy the most conspicuous and prominent places...Clumps of the flame coloured azalea should shine near those of the purple rhododendron, for as they flower at the same season the contrast is as a rich purple robe with gold. It requires the nicest judgment to intermix even those plants which contrast or harmonize best."

15

While the nurserymen were developing new and more colourful hybrids for the suburban garden, the rising class of professional gardeners working for the old landed aristocracy and the new industrialists on the larger estates began mastering the rhododendron's cultural requirements, such as segregating them from herbaceous plants and massing them in woodlands that had acidic soils. Robert Fish, head gardener for Putteridgebury and a horticultural journalist, promoted the arrangement of rhododendrons at Dysart House as a model for planning garden layouts of rhododendrons. He wrote that rhododendrons were to be "thrown together in groups and bold sweeping borders in grounds traversed with gracefully curved walks and these again bordered with irregular margins of turf." Head gardeners like Joseph Paxton

16

at Chatsworth and Philip Frost at Dropmore, as Brent Elliott relates in his chapter "Rhododendrons in British Gardens: A Short History" in

The Rhododendron Story

, moved the brightly coloured hybrids into woodland settings and began using the self seeding purple

Rhododendron ponticum

to decorate woodland and to replace the "laurel" as a covert for game.

In the 1860s and '70s, these and other professional gardeners now took on hybridizing rhododendrons for their estate owners, by raising new hybrids from seed, growing on, and flowering Joseph Hooker's flamboyant and exotic Himalayan species that had been picture in

Rhododendrons of the Sikkim Himalayas

. Robert Fortune of the East India Company went to China and smuggled out the tea plant that got the Ceylon, Assam, West Bengal tea estates up and growing, collecting and introducing ornamental plants for the Royal Horticultural Society, such as new varieties of

Chrysanthemum

, the magenta

Primula japonica

, and

Rhododendron fortunei

, among many others. Fortune's rhododendron became one of the parents with Hooker's Himalayan

R. griffithianum

for a number of hybrid shrubs with large flowers in looser trusses. One named 'Loder's White' after its originator, Lord Loder of Leonardslee, was a connoisseur's or collector's plant, while the other, named 'Pink Pearl', vied both in name and colour with the earlier magenta 'Cynthia' for position as the centrepiece of the Victorian suburban front lawn.

17

|

|

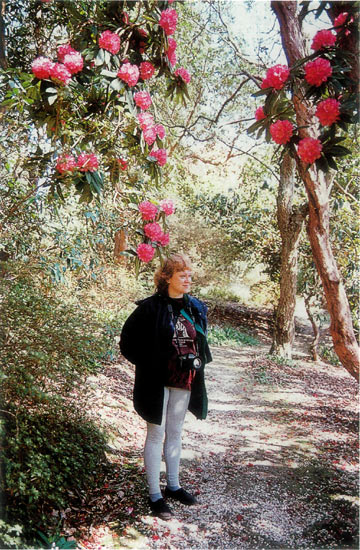

Susan Baker of Vancouver, British

Columbia, with R. 'Luscombei' at Leonardslee, Sussex, England. Photo by Clive L. Justice |

In the 1870s, rhododendron hybrid specimens continued to grace the grass swards. Massed hybrids were still among the shrubs to be planted in numbers in formal shapes - diamonds, triangles, and half circles with other shrubs in grass boulevards along drives, carriage ways, and parades. Favourite places for groupings on large estates were along the edges of lakes and on islands both in water and the centre of driveways in front of great houses. In the latter they kept company with the weeping Himalayan

Cedrus deodara

or the stiffer but blue foliaged atlas cedar,

C. atlantica glauca

. Fine examples of waterside rhododendron plantings occurred at Lord Digby's Dorset garden, Minterne, and the landscape gardens of Claremont and Stourhead, while a photograph of the 80-foot-diameter

R. ponticum

at St. Leonard's forest, Horsham, taken around 1910 recorded the spread of a single plant by layering.

18

In the milder counties the subtropical garden was popular. It included rhododendrons such as the red, pink, and white

Rhododendron arboreum

with Hooker's big leaved

grande

and

falconeri

species combined with gunneras, pampas grass, cordylines and even subtropical palms. Beatrice Parsons' fine and colourful water colours that illustrated J. C. Millais' majestic 1917 tome (really a Victorian book)

Rhododendrons and the Various Hybrids

depicts "A Woodland Path at Leonardslee in May" - yellow, orange, and pink azaleas with red, cerise and white ('Loder's White'?) rhododendrons under a pink soulange magnolia with a fan palm and several Douglas fir a little farther along the path.

|

|

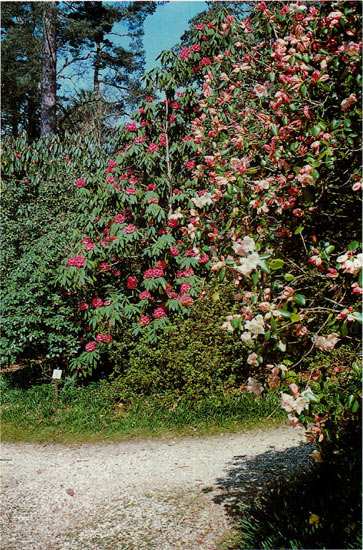

Rhododendrons at Leonardslee

in Sussex, England. Photo by Clive L. Justice |

The Cornwall gardens of Trebah, Glendurgan, and Penjerrick are among many examples of gardens of exotic plants set in small narrow valleys or coombes with streams and ponds that fall down to the ocean. Many are now preserved and maintained under the National Trust Gardens Scheme. The National Trust for Scotland gardens of the Victorian period like Arduaine, Kilmelford on Loch Melfort, and Brodick Castle on the Isle of Arran have hillside forest areas with plantings of hundreds of rhododendrons. Arduaine is unique in that the rhododendrons are on a hillside under a woodland of the deciduous Japanese larch. Those rhododendrons in Brodick Castle grounds are in a forest of Pacific Northwest coastal Douglas fir.

At the close of Victoria's century William Robinson's book

English Flower Garden

, first published in 1883, hardly mentions the rhododendron. It was not until the fifth and sixth editions that he got around to stating: "The glory of spring in our pleasure gardens is the rhododendrons," while advising gardeners in the fifth edition to "...show the habit and form of the plant. This does not mean that they may not be grouped or massed just as before, but openings of all sizes should be left among them for light and shade, and for handsome herbaceous plants that die down in winter, thus allowing the full light for half the year of evergreens."

19

The last words, however, on the use of rhododendrons in the Victorian garden go to Gertrude Jekyll in her book

Wood and Garden

published in 1899, for it was in her garden at Munstead Wood in Surrey that she described the culture and arrangement of rhododendrons: "Now in the third week of May, rhododendrons are in full bloom on the edge of the copse... During the previous blooming season [to planting] the best nurseries were visited and careful observations made of colouring, habit and time of blooming. The space they were to fill demanded about seventy bushes, allowing an average of eight feet plant to plant - not seventy different kinds, but perhaps ten of one kind, and two or three fives, and some threes and a few single plants, always bearing in mind the ultimate intention of pictorial aspect as a whole...to make pleasant ways from lawn to copse; to group only in beautiful colour harmonies; to choose varieties beautiful in themselves; to plant thoroughly and well and to avoid overcrowding...Before planting the ground, of the poorest quality possible was deeply trenched [double dug], and the rhododendrons were planted in wide holes filled with peat, and finished with a comfortable "mulch," or surface covering of farmyard manure. From this a supply of grateful nutriment was gradually washed in to the roots."

Miss Jekyll concludes:

"It may be useful to describe a little more in detail the plan I followed in grouping rhododendrons, for I feel sure that any one with a feeling for harmonious colouring, having once seen or tried some such plan will never again approve of haphazard mixtures...The colourings seem to group themselves into six classes of easy harmonies, which I venture to describe thus:

1. Crimsons inclining to scarlet or blood-colour grouped with claret-colour and true pink

2. Light scarlet rose colours inclining to salmon

3. Rose colours inclining to amaranth

4. Amaranths or magenta-crimsons

5. Crimson or amaranth-purples

6. Cool clear purples of the typical

ponticum

class both dark and light grouped with the lilac white...But the purples that are most effective are merely

ponticum

seedlings chosen when in bloom in the nursery for their depth and richness of cool purple colour."

20

Miss Jekyll thought highly of

Rhododendron ponticum

. Its genes helped to produce some of the most beautiful garden plants ever created, and it is sad and ironic that purple ponticum's successful and enthusiastic adaptation to the English countryside and woodlands caused it to be regarded a common pest. It met all the requirements of Mr. Darwin's thesis in

The Origin of Species by the Means of Natural Selection

- success in variation, environmental adaptation, and survival. What more could you ask of a plant for the garden.

End Notes

1

Joseph Banks died in 1820; William Hooker was appointed Director of Kew Gardens 21 years later in 1841.

2

After

Rhododendrons of the Sikkim Himalayas

was published in 1849 as Alice Coates relates in

The Book of Flowers

(1973) "...came chromo-lithography - cheap, lurid and vulgar - and the [botanical] art...was temporarily under a cloud."

3

Rhododendron thomsonii

with its deep blood-red bells, six or more with a skirt of thick green leaves, became a pattern on a full service of Wedgwood china. It would have fit right in with the times. Today it would probably be considered overly garish fit more for a T-shirt. Thomas Thompson after whom the Hookers named the rhododendron was superintendent of the Calcutta Botanical Gardens. He was a personal friend of the younger Hooker.

4

One such book published in 1759 gave detailed soil recipes or, as called in the book, composts for almost every crop of vegetable or type of flower, along with sowing times and a calendar of the necessary work each month of the year in the kitchen, fruit, pleasure gardens and wood, etc., with a dissertation on forest trees.

The British Gardener's Calendar

by James Justice, F.R.S., went into several printings including an Irish edition in the last half of the eighteenth century. Five varieties of American rhododendrons (

Chamerododendron

) are noted in the American Tree Seeds list at the end of the book, all to be sown in spring in boxes or pots. It is unlikely that all were rhododendrons. Most probably

Kalmia

and

Andromeda

or

Pieris

were included.

5

A quote from William Mason,

The English Garden, A Poem in Four Volumes

as it appears in J. C. Loudon,

An Encyclopedia of Gardening

(1850 edition, Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans, London) page 246. John Claudius Loudon published his

Encyclopedia

in 1834. The 1850 edition was corrected and improved after his death in 1843 by his widow Jane Loudon. The encyclopedia was only one in a long list books and periodicals he wrote. See Dumbarton Oaks Colloquium on the History of Landscape Architecture VI, Elisabeth B. MacDougall editor,

John Claudius Loudon and the Early Nineteenth Century in Great Britain

, 1980, Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, District of Columbia, 134 pages.

6

Hunt, John Dixon, and Willis, Peter, Editors.

The Genius of the Place, The English Landscape Garden 1620-1820

(1975, Paul Elek, London), Part4, "Picturesque Taste and the Garden," pages 318 cf.

7

Philip Miller published

The Gardener's Dictionary

that ran to eight editions. The eighth edition came out in 1768. The sixth edition started using the Linnean system of binomial nomenclature for plants and with the eighth there was a consistent adoption of the genus, species, and varietal names set out by Linneaus. See: Blanche Henrey,

British Botanical Literature before 1800

(1975, Oxford University Press, London), Vol. II, pages 213-219.

8

The American garden of Loudon was an arboretum-like layout of individual trees and plant specimens from America displayed in a grass sward. See: J. C. Loudon,

An Encyclopedia of Gardening; & etc.

(1850, Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, London) Book 4, page 101l cf.

9

The Western azalea,

Rhododendron occidentale

, while grown in the wet woodland garden is more famous as a parent for the bright verging on the garish: orange, yellow, and red flowered hybrid azaleas that were grouped under the names of the nurseries - Waterer, Knaphill, and Sunningdale hybrids - that bred and introduced them to mid and late Victorian gardens. They became the outdoor equivalent of the more popular and even more brightly coloured hybrids and species rhododendrons from the southeast Asian tropics grown in heated greenhouses and called collectively "Javanicums." These latter, competed with the exotic epiphytic orchids for attention of Victorian collectors and gardeners.

10

It is claimed that the Crusaders brought

Rhododendron ponticum

from the part of Asia Minor lying between the Black and Caspian seas or the Ancient Roman Empire province of Pontica to Spain. Since its introduction into the British Isles and Ireland about 1763 from southern Spain it has taken just 200 years to adapt and spread into the woodland areas of southeast England, into Wales and the western Midlands and the moorlands of Ireland. In the latter it has replaced the gorse, broom and heather to become in wood and moorland much as the dandelion has done for meadow and suburban lawn.

11

The first hybrid rhododendron named was a cross between an evergreen rhododendron and a deciduous azalea,

R. ponticum

and the American

R. periclymenoides

(formerly

nudiflorum

) and named 'Odoratum' with strongly scented mauve flowers. The first of the

R. arboreum

crosses bore latinized hybrid names like the magenta red 'Altaclarense' (Latin for Highclere, Lord Caernavon's estate at Newbury where it originated) and 'Nobleanum'. Then they began to name hybrids for the nurserymen who developed them: 'John Waterer', 'Gomer Waterer', and 'Cunningham's White'; closely followed by hybrids with names of ladies in the aristocracy: 'Lady Eleanor Cathcart' and 'Princess Ena', along with important industrialists like 'Sir Robert Peel'. The latter hybrid was named for a wealthy cotton manufacturer and printer of calico, the father of the British prime minister of the same name. Rhododendron 'Sir Robert Peel', a wine red, was planted and is still extant as a street tree in Rotarura, New Zealand.

12

The head of 5-7 flowers on a hybrid rhododendron make up an egg-shaped

truss

. With hybrid rhododendrons especially during the early and mid Victorian period the objective was not only to produce bright colours but also a plant where each flower was full faced and closely and tightly arranged together to form a perfect egg shaped or rounded cone. The perfect trusses of flowers were formally presented on an irregular rather informal plant. The hybrids with loose (floppy) flower trusses became popular in the late Victorian/Edwardian period.

13

Street, Fredrick,

Rhododendrons

(1965, Cassell & Company Ltd., London), Chapter two, "Hybrid Vigour," page 9.

14

The garden at Down House, Charles Darwin's home in Kent, was in the Loudon's Gardenesque Style, vine covered house and all. Duncan Porter's article in the winter and spring 1998 ARS Journal relates that Darwin's writing and hybridizing on the genus was extensive. Whether or not he grew rhododendrons as ornamentals is not at all clear. However, in the mid 1850s Kew Gardens sent Mr. Darwin 12 different plants of Joseph Hooker's Sikkim rhododendrons plus an evergreen shrub, a barberry from South America to which Hooker Sr. had given the species epithet

darwinii

It is a comely ornamental garden plant with clusters of bright orange flowers, even if a bit prickly. See: Cynthia Postan,

The Rhododendron Story

(1996, RHS, Wisley), page 58.

15

In mid nineteenth century "harmony" and "contrast" in music and art meant much the same thing. Red, yellow, and blue were in harmony when used together, but red and orange were not. See: Brent Elliott (1993), "A Spectrum of Colour Theories," Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society (JRHS), 118: 573-75; Cynthia Postan, Ed.,

The Rhododendron Story

(1996, The Royal Horticultural Society, London), chapter 14, Brent Elliott, "Rhododendrons in British Gardens: A Short History", pages 156-86.

16

Joseph Paxton designed the great glasshouse, the Crystal Palace, for Prince Albert's Great Exhibition of 1851. He also found time to compile a

Botanical Dictionary

(1840) which listed over 60 hybrid and species rhododendrons. He was also a politician becoming Liberal MP for Coventry in 1864.

17

These names and the hybrids that bore them would become treasured garden plants well after the age of Victoria. However, there would be revulsion and rejection by a few. 'Pink Pearl' along with 'Nobleanum Venustum' and cerise 'Cynthia' would in the order stated qualify for feminist mid twentieth century writer Germaine Greer's "Revolting Garden" column in her book

Private Eye

, for her expressed revulsion of "bloated heads of rubbery blooms of knickers pink, dildo-cream and gingivitis-red." Ann Scott James in her book on Sissinghurst, Vita Sackville West's and Harold Nicholson's garden in Kent, relates that in the early 1920s neighbour Captain Collingwood "Cherry" Ingram tried to interest Vita in liking rhododendrons and including them in the development at Sissinghurst. As Harold hated rhododendrons, Vita never succumbed to the genus except for a few in the azalea group. See: Ann Scott-James,

Sissinghurst, the Making of a Garden

(1974, Michael Joseph Ltd., London) pages 26, 48, 69.

18

Millais, J.G.,

Rhododendrons and the Various Hybrids

(1917, Longmans Green and Co., London) facing page 12.

19

Elliott, Brent, "Rhododendrons in British Gardens, A Short History" in

The Rhododendron Story

(1996, The Royal Horticultural Society, London), page 171.

20

Jekyll, Gertrude,

Wood and Garden

(1899, Longmans Green and Co., London), pages 64-67. Antique Collectors' Club Ltd., Suffolk, England, facsimile edition of

Wood and Garden

published in 1981, still in print.

Clive Justice, a member of the Vancouver Chapter, is a landscape architect and student of the history of rhododendrons in the landscape.