Tips for Beginners: A Case for Deadheading

Mike Trembath

Aldergrove, British Columbia

Canada

In the popular garden magazine, Gardens West (July 1990), readers were told that deadheading rhododendrons was unnecessary for good bloom. Mike Trembath disagreed and responded to the following statement: One dead-head job you do not have to do is removing the spent flowers on the rhododendrons. It is a sticky job and the plants will bloom well the next year even though the plants are not deadheaded. The only time I would do it is on a shrub that was by my front door or any other place where the spent blossoms are an eyesore.

Well, yes...maybe...sometimes...if you're lucky...and have the right varieties. I take exception to such a large generality, and fear it is a mite misleading. Certainly the faded trusses can be unsightly, and certainly some of them rival old fashioned fly paper for stickiness, but you do not deadhead for cosmetic reasons alone.

I have lived with, collected, grown, and looked at rhodies for some thirty years. More important than the resulting improvement in appearance, deadheading prevents seed production and permits the more rapid development of axillary new growth buds.

The largesse with which seed is produced by rhododendrons seems to be a varietal pattern, i.e., some produce small, almost non-apparent seed pods; others flaunt great capsules like mini-bananas. Although rhododendron seeds are small, the number of seeds per capsule, or even segment of capsule, is staggering. When you consider that your average garden hybrid carries a truss on every terminal branch (you hope) of eight to twenty flowers each of which may develop a capsule containing millions of seeds, and when you consider that the production of viable seed is a prime directive for the plant kingdom, you begin to appreciate the demands made on the plant's nutritional system - demands which are more imperative than those for growth and new bud set.

Those varieties prone to set abundant seed show more marked changes: un-deadheaded, the foliage produced is smaller, flower buds are absent or uncharacteristically small, and the branch may even die and be shed. Permitted to continue without deadheading, the entire plant looses vigor and may die. I know there are other factors involved, and seed production is not the sole cause of demise even in my above description, but plants stressed by heavy reproductive duties are ill equipped to withstand other stresses, such as competition or drought.

|

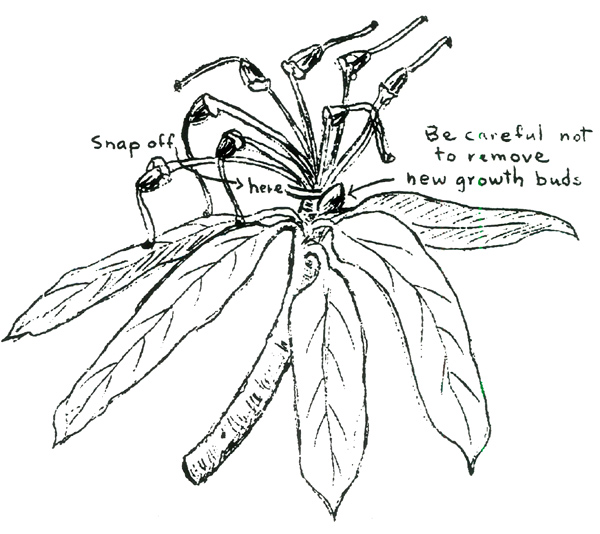

Individual branches of rhododendrons support a terminal whorl of leaves with a central bud. The bud may be a flower bud or a leaf bud. In the latter case, spring growth causes the bud to grow - straight ahead, as it were, the branch is lengthened and forms another terminal whorl of leaves and its central bud. If the central bud is a flower bud, growth of the branch occurs from the tiny axillary buds that lie at the junction of the leaf stalks and the main stem. When the spent flower is snapped off, one, or more, of these small buds will lengthen and grow and create the next branch (or branches) with their leaves and terminal buds. If the spent truss is not removed, development of the axillary buds is often delayed. Delayed new growth may fail to produce flower buds, or may be insufficiently ripe to withstand a hard winter.

The writer of the article is right - you don't have to deadhead your rhodies. However, the job is relaxing in its sheer mindlessness, so if you have the time, and don't mind having the thumb and forefinger of your right hand glued together (I've yet to find a solvent), your plants will be stronger and healthier and will produce more flowers.

Mike Trembath is a member of the Fraser South Chapter.