Our Eastern Native Azaleas in the Twenty-first Century

Sandra F. McDonald

Hampton, Virginia

Based on a talk given at the ARS Annual Convention, Burlington, Massachusetts, May 26, 2000.

Introduction

Balancing human wants and needs with environmental concerns is a very complicated process, and I can only touch on the high points in this short article. We need places to live, trees for lumber and paper, farms to produce food, and clean water to drink and clean air to breathe. Many of us would also like to have natural places to preserve our beloved species of native azaleas and rhododendrons as well as all manner of other species. We want these natural places for people to enjoy in the long term.

I have been interested in the native azaleas for about twenty-five years and have become more concerned about their gradual demise and need for protection during field trips in recent years with Middle Atlantic Chapter's Species Study Group members George McLellan, Bill Bedwell, Frank Pelurie, Don Hyatt, Jim Brant, Ken McDonald, and occasional others. Ken and I took our first trip with Joan Winter to see the native azaleas on Gregory Bald on June 23, 1979. Closer to home we had scouted around looking at the populations of some of the lowland native azaleas.

The deteriorating environment has also been one of my concerns, and when asked to prepare a talk about the outlook for native azaleas for the ARS Annual Convention in 2000, I decided to put together information from several sources and my personal experiences. The book Blue Ridge 2020, An Owner's Manual by Steve Nash (1999) provided basic inspiration and much information, broadly supplemented by other sources.

To achieve the goals of preservation of species and a healthy environment we need the working together of government, businesses, farmers, foresters, environmentalists and the public so that the mutual goals can be achieved with the least damage to any one segment of those involved. Businesses need to be able to make money to survive; farmers need to earn a living from their farming; and foresters need to farm trees and look after the well-being of the natural forests.

|

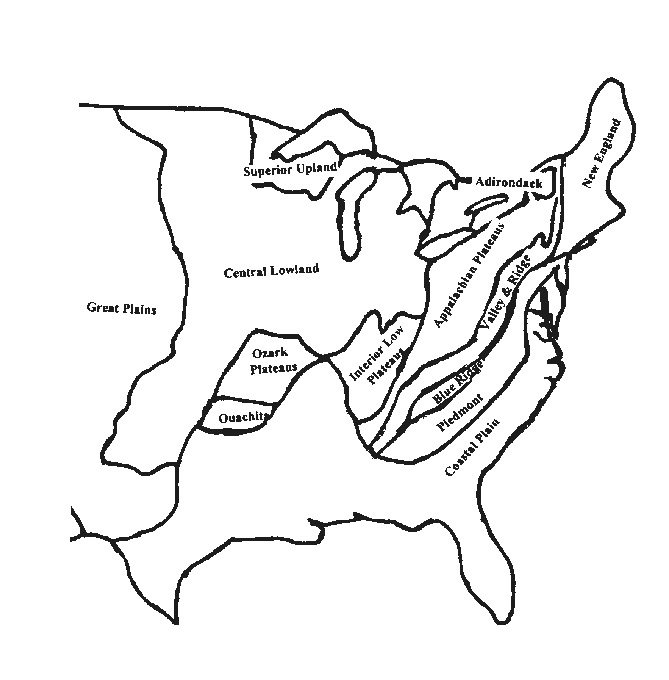

| Physiographic provinces of the Eastern United States. |

Physiographic Provinces, Habitats, and Species

The species of eastern native azaleas begin in northeast coastal Canada with

Rhododendron canadense

and spread down the eastern seaboard and inland into the mountains. The various species extend across the South into eastern Texas where

R. viscosum

and

R. canescens

are found.

Rhododendron prinophyllum

is in eastern Oklahoma and in the Ozarks.

|

|

R. cumberlandense

off the Cherohala Skyway in 1999.

Photo by Sandra F. McDonald |

The eastern United States, especially the Blue Ridge Ecosystem, contains a large concentration of species of native azaleas. Fourteen eastern species are generally accepted, but recently Katherine A. Kron (1999) and Mike Creel identified the new species R. eastmanii . Others consider R. viscosum to be several different species instead of just one.

Most of the mountain species are found in the Blue Ridge Ecosystem. There are seven national forests which provide good habitat for native azaleas within the Blue Ridge Ecosystem. These forests are the Chattahoochee National Forest at the south end, the Sumter National Forest, the Cherokee National Forest, the Nantahala National Forest, the Pisgah National Forest, the Jefferson National Forest and at the north end the George Washington National Forest.

Roadless areas make up only 3 percent of land in the entire Southern Appalachians region with more than a third of it being in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. It is important to maintain some land without roads to protect some species, especially animal species, which have trouble surviving in areas frequented by man. Many species of animals and plants have become extinct because of man's activities.

Stuart Pimm, University of Tennessee theoretical ecologist, said, "In most of the other parts of the world they've lost their forests, or they're losing them. We in the East may have the finest deciduous forests left on the planet. In the future, this may be one of the only parts of the world where you can walk in forests for days at a time" (Nash 1999, p. 5).

Predicting past extinction rates into the future is absurd for no other reason than that the ultimate cause of these extinctions, the human population, is increasing exponentially (Pimm, et al. 1995).

Extinction is an incremental process proceeding slowly at first. But by the time many species are declared "endangered," federal officials say the chances for their long-term survival are nearly foreclosed because more than 90 percent of their habitat has already been destroyed (Nash 1999, p. 5). There is an illusion of changelessness, but there is change.

Kron (1993, 1995) has done taxonomical studies of our native azaleas that provide helpful information. The eastern species are listed below together with some threats that have been observed by our Species Study Group in field trips.

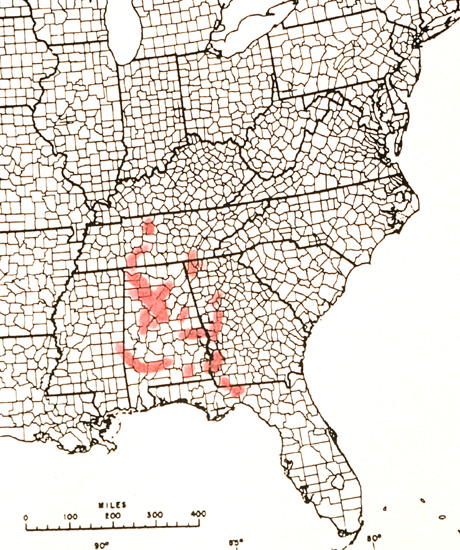

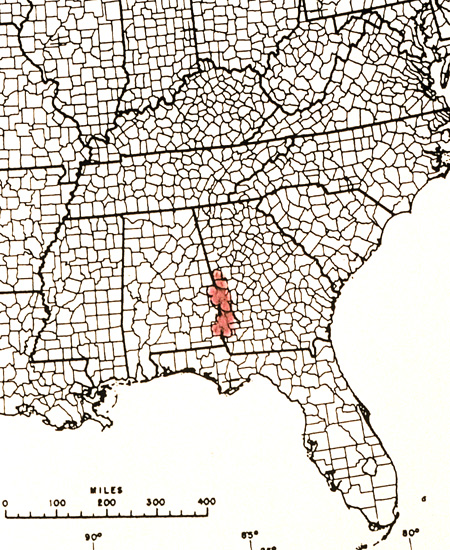

Rhododendron alabamense . This species is found in Alabama and adjacent Tennessee, and Georgia and Florida. Its habitat is upland woods, bluffs and hillsides, along watercourses, and in stream bottoms from about sea level to 500 m (1700 ft). Its main flowering season is April and May, but sometimes it blooms in March or June. Rhododendron alabamense has a limited distribution and is threatened by development and in northern Alabama by strip mining.

|

|

R. alabamense

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

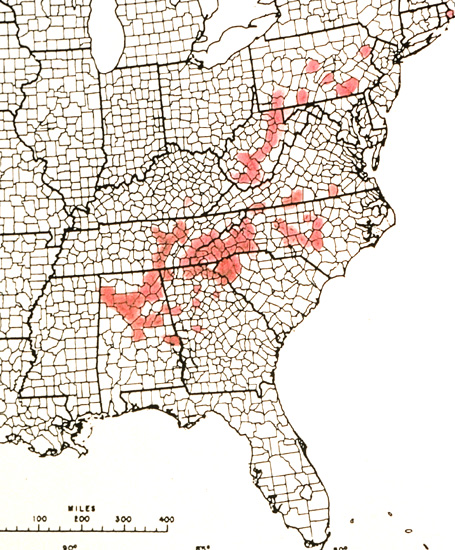

Rhododendron arborescens Rhododendron arborescens is found in West Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia and Alabama. Its habitat is along mountain streams, on shrub balds and in moist woods at elevations of 300 to 1500 m (1000 to 5000 ft). Flowering is from May to August, and occasionally as early as April or as late as September. This species helps hold stream banks with its fibrous root system and is somewhat impacted by development.

|

|

R. arborescens

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

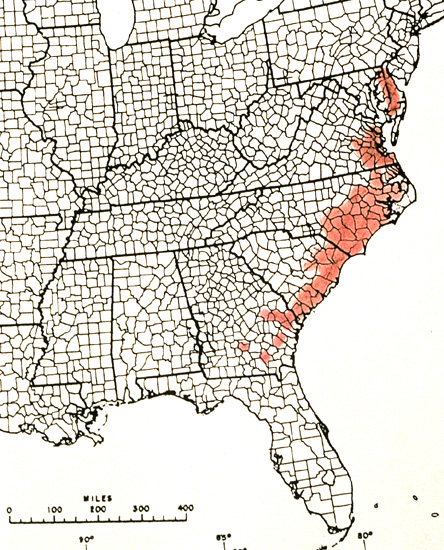

Rhododendron atlanticum . This species extends from Delaware to southeastern Georgia along the Atlantic Coastal Plain. It grows in sandy pinelands, swamps, shrub bogs, and along streams at sea level to 150 m (500 ft). It usually flowers in April and May, although it may flower as early as March. Rhododendron atlanticum grows in an area where population is expanding very rapidly along the East Coast. Besides threats from business and housing developments, some treatments for vegetation control under power lines are diminishing its numbers.

|

|

R. atlanticum

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

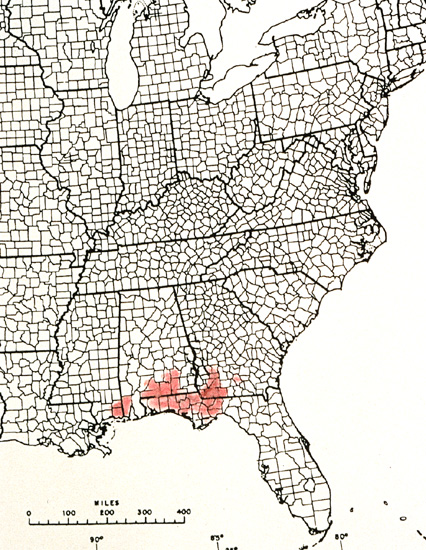

Rhododendron austrinum . This species is found in the panhandle of Florida and in Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. It is found in upland mixed mesic hardwood forests, bluffs of rivers or stream banks, river bottoms and swamps from sea level to 100 m (300 ft). It flowers in March and April and occasionally in May. It is being threatened by development in Georgia.

|

|

R. austrinum

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

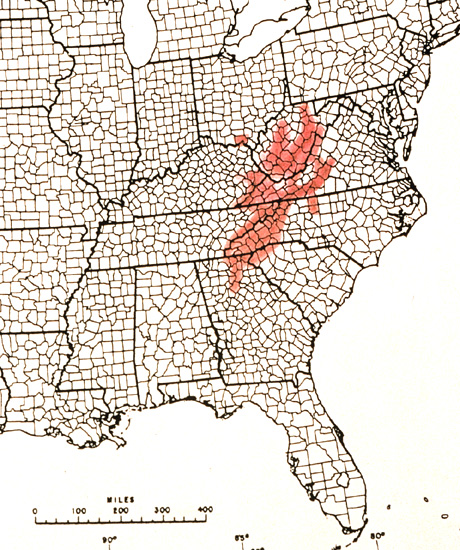

Rhododendron calendulaceum . Rhododendron calendulaceum is found in the mountains of Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. It grows in open, dry sites on southern and western exposures of hills and mountainsides at elevations of 180 to 1000 m (600 to 3300 ft). Flowering time is from May to July. Some R. calendulaceum are being destroyed by home building and town expansion as the population in the mountains expands and more summer homes and year-round homes are built. It is also often dug by collectors.

|

|

R. calendulaceum

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

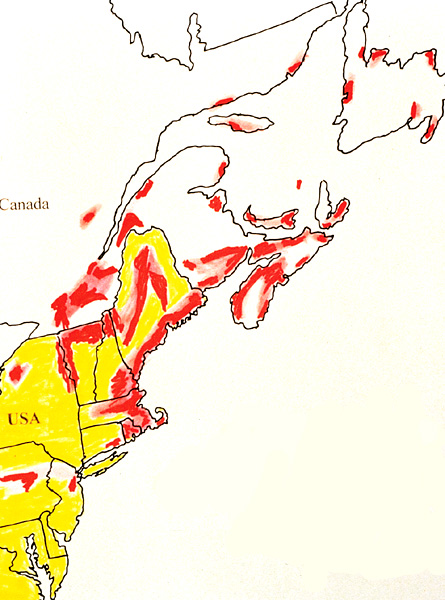

Rhododendron canadense . This northern species is found in Newfoundland and Quebec and south through New England to eastern Pennsylvania and northern New Jersey. It grows in moist to dry coniferous or deciduous forests, thickets, open rocky areas, lake margins, bogs and swamps from sea level to about 1900 m (6300 ft). Flowering time is April through July. The species still seems to be plentiful in remote locations although reduced in populated areas.

|

|

R. canadense

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

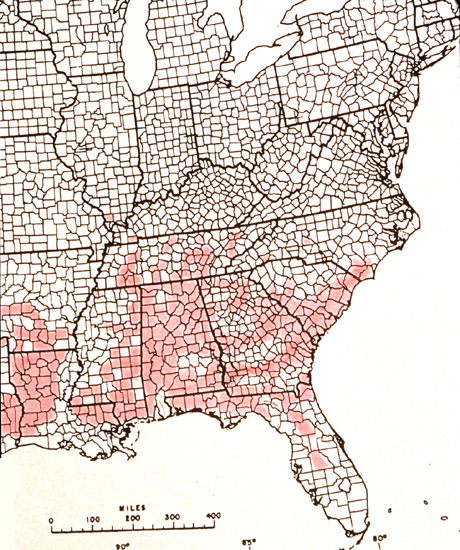

Rhododendron canescens . This species is distributed from Tennessee and North Carolina to South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Florida, eastern Texas, eastern Oklahoma and Union County, Illinois. It grows on river bottoms and stream banks, low flatwoods, dry clearings and open woods from sea level to 500 m (1600 ft). Flowering time is March and April and occasionally as late as June or July. The species is still plentiful probably because of its wide distribution.

|

|

R. canescens

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

Rhododendron cumberlandense (formerly bakeri ). This species grows on the Cumberland Plateau in westernmost Virginia, eastern Kentucky, West Virginia, eastern Tennessee and along its border with North Carolina, northern Georgia and northern Alabama. It grows in mixed mesophytic forests on ridge-tops above 900 m (3000 ft) and occasionally is found at lower elevations. It blooms in late June and July. Some of this species is located in parks and should be safe at least in those locations although it is disappearing in populated areas.

|

|

R. cumberlandense

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

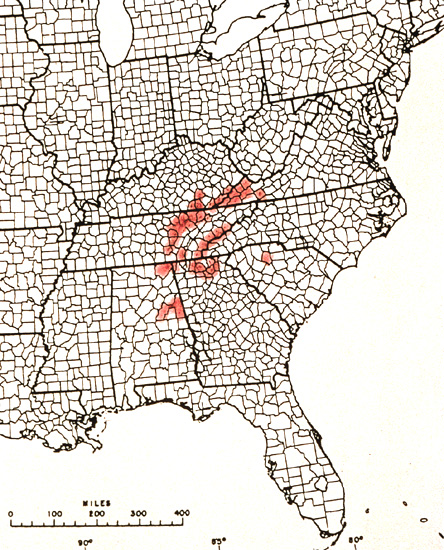

Rhododendron flammeum (formerly speciosum ). This species is found in Georgia and South Carolina in upland woods, dry slopes and ridges, bluffs of rivers or stream banks and sand hills from sea level to 500 m (1700 ft). It flowers in April. This species has been greatly diminished because it grows across Georgia in a belt in which the city of Atlanta and its suburbs have been developing and wiping it out.

|

|

R. flammeum

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

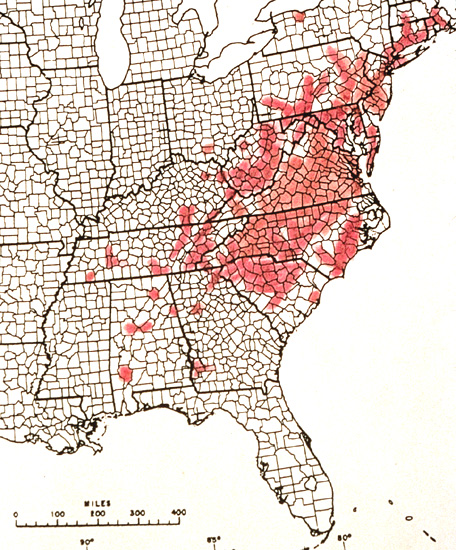

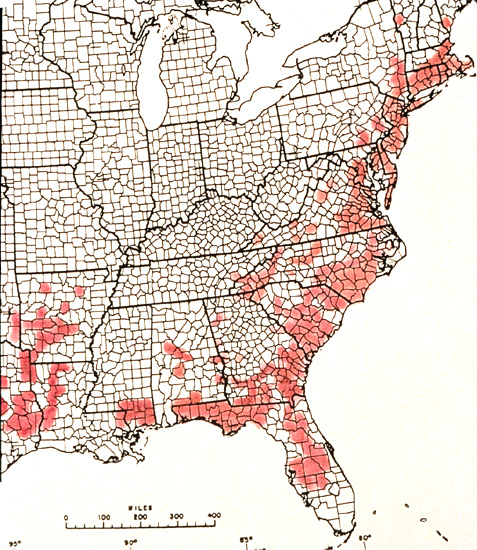

Rhododendron periclymenoides (formerly nudiflorum ). This azalea is distributed from Vermont, Massachusetts, and New York, south and west to western Tennessee and east to the Atlantic Coastal Plain and south to the Carolinas, Georgia and Alabama. Habitats include upland woods, bluffs and stream banks, ridge tops, and sandy open woods from about 100 to 1000 m (300 to 3300 ft). It flowers from March to June. Development has been wiping out this species because it is found in areas of population growth.

|

|

R. periclymenoides

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

Rhododendron prinophyllum (formerly roseum ). This species is found in New Hampshire and Vermont south to Ashe County, North Carolina, and to eastern Kentucky and parts of Ohio. It is in Union County, Illinois, and southeastern Missouri, south to Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma. Isolated populations occur in Transylvania County, North Carolina, and Cherokee County, Alabama. It grows on bluffs and stream banks, open wooded slopes, and acid bogs, from about 150 to 1500 m (500 to 5000 ft). It flowers from March through June. This species is faring well so far because of its widespread distribution. In some areas it is threatened by population growth.

|

|

R. prinophyllum

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

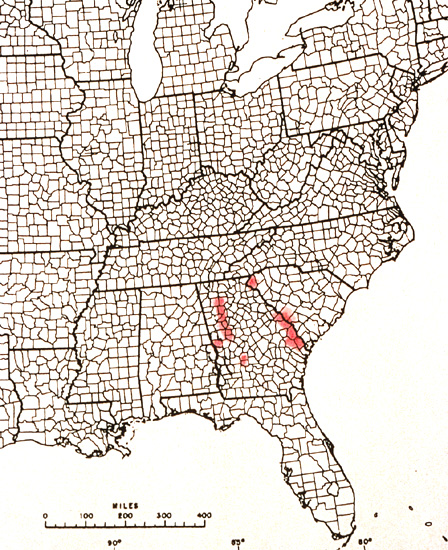

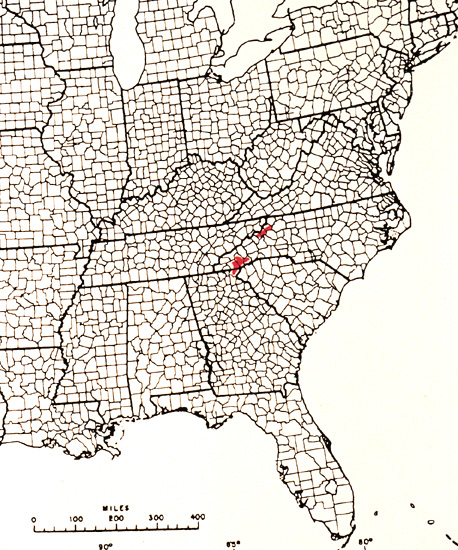

Rhododendron prunifolium . Rhododendron prunifolium has a very restricted distribution along the central Georgia and Alabama state line. It grows in wooded ravines along streams in mixed pine-hardwood woods at elevations of about 90 to 200 m (300 to 700 ft). Flowering time is June through August. This species should be protected because of its limited distribution.

|

|

R. prunifolium

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

Rhododendron vaseyi . Rhododendron vaseyi grows in bogs, thickets, and forests in North Carolina at 900 to 1830 m (3000 to 6100 ft). It flowers in late April, May, and June. This species has a very limited distribution, but is fairly well protected where it does exist.

|

|

R. vaseyi

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

Rhododendron viscosum . This is a very wide-ranging species from Vermont and Maine to the Florida peninsula and west to Texas and north to Arkansas. Rhododendron viscosum has been segregated into as many as four species: R. coryi , R. oblongifolium , R. serrulatum , and R. viscosum . It can be found in wet habitats along stream banks, swamps, low flatwoods, shrub balds and acid bogs, from sea level to 1500 m (5000 ft). It may flower as early as March in some areas and as late as December at the southern limits of its range. Rhododendron viscosum has a wide distribution but is noticeably depleted in built-up areas where it used to grow.

|

|

R. viscosum

distribution.

Map prepared by George McLellan |

Rhododendron eastmanii . This is a proposed new species by Kathleen A. Kron (1999) and Mike Creel. It was found in Orangeburg and Richland counties in South Carolina. It grows on north-facing slopes with well-drained, nearly neutral soils, often near limestone. Flowering is in early May. This proposed species should, of course, be protected because of its limited distribution.

|

|

New species

R. eastmanii

in South Carolina.

Photo by Mike Creel |

Destructive Policies and Some Remedies

Today habitats of our natives in the East are rapidly disappearing because of housing and business development. We are losing genetic diversity as numbers of individual plants decrease.

We can ease the destruction caused by development and sprawl in several ways. Some solutions include finding ways to promote compact and efficient growth. All levels of government need to work with environmentalists, citizens, farmers and developers. Cluster development, zoning and conservation easements and "smart growth" techniques for development in areas that can already provide infrastructure are all practical remedies.

|

|

Mountain homes where native vegetation was cleared.

Photo by Sandra F. McDonald |

Growth in agricultural and natural areas should be restricted. Farms are needed to produce food for the human population, but farms are being crowded out to less desirable land to make room for houses. Farming on less desirable land does much more damage to the environment than farming on flat, prime farmland.

Air quality is deteriorating. The air is becoming more polluted. Pollution from coal burning power plants threatens our pristine areas in the mountains. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has documented that national parks, wilderness and rural areas have recorded increasing concentrations of air pollution over the last ten years. Chemical air pollution can kill plants and has caused denuding of a mountaintop. Dead trees in many places on the Blue Ridge Parkway result most likely from attack by the woolly adelgid, but the trees were in a weakened condition because of air pollution and this probably made them more susceptible to the woolly adelgid.

One remedy for air pollution and climate change is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from power plants, autos and other sources. We need to look at the long-term implications of climate change. We should be concerned about other kinds of air pollution such as ozone and do whatever is necessary to keep the pollutants within safe ranges.

|

|

Increasing haze in the mountains of North Carolina.

Photo by Sandra F. McDonald |

Air quality measurements (ozone, smog) got worse in 1999 according to government reports. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that the global warming rate has accelerated, and in the last twenty-five years it achieved the rate previously predicted for the 21st century (2 degrees Celsius per century) (Karl 2000). A recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects a "potentially devastating" global warming of 1.4 to 5.8°C (2.52 to 10.44°F) over the coming century (Environment News Service January 22, 2001). This forecast is for higher temperatures than the same panel proposed five years ago. The Greenland Ice Sheet is melting, and glaciers are melting faster. The 1990s was the warmest decade on record. The Alaska permafrost rose 6.3°F (Wuethrich 2000).

Manipulation of watercourses, for example by stream widening after flooding, impacts plant habitat. These projects disrupt the water flow and produce more flooding downstream. We should not unnecessarily change stream beds or drain wetlands because this causes loss of habitat for many plants including R. arborescens , R. viscosum , R. canadense , and R. maximum . We should prevent water pollution.

|

|

Modified water course of Brush Creek.

Photo by Frank Pelurie |

Forestry and farming policies such as clear cutting allow greater soil erosion. Logging done in the area of Roan in the late 1800s and early 1900s led to erosion and repeated flooding of towns which finally ended the clear cutting there (Laughlin 1991). The floods in 1901 and 1902 prompted the Department of Agriculture to examine the situation and generate an inch-thick report on conditions in the southern Appalachians. The report documented harmful farming practices, clear cutting, landslides and erosion problems which had been caused by land owners and lumbering concerns. The government recommended the establishment of a national park in southern Appalachia. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park was designated a National Park on June 15, 1934.

The Champion Coated Paper Company (later the Champion Fibre Company and the Champion Paper and Fibre Company) was the principal logging company around Roan. Champion's logging operations continued until 1937, and all trees larger than six inches in diameter were removed. A trainload and more than a dozen truckloads of rhododendrons were removed and shipped north to botanical gardens and to landscapers. The plateau that supported the largest natural rhododendron field in the United States was nearly denuded.

Roan Mountain State Park was created in the 1950s by the state of Tennessee. Roan has since regenerated greatly although some species were lost and some are still endangered. Now that Roan is protected we can even find a few of the rare Lilium grayi.

|

|

Jim Brant (yellow backpack) and Ken McDonald (red backpack) enjoying

the view and R. calendulaceum at Engine Gap on Roan Mountain. Photo by Sandra F. McDonald |

|

|

R. catawbiense

and

R. calendulaceum

on Roan Mountain.

Photo by Sandra F. McDonald |

A particularly destructive practice is root raking which pulls out nearly all plant roots and along with other management practices ends up delaying for a long time if not totally preventing further regeneration of native azaleas and other vegetation.

Trees are needed for paper production and lumber. Tree farming seems to be a more environmentally sensible way to do this rather than logging old forests. But it would be even more preferable to have some species diversity and to have more than one-crop tree plantations. Even allowing growth of native azaleas and other native plants around the edges of the plantations would give a boost to genetic diversity and species survival.

|

|

Logging clear-cut with whole tree removal.

Photo by Frank Pelurie |

Logging small areas is not as destructive as the larger scale clear cutting. In our forestry policy we should steer away from clear cutting and do selective cutting instead to avoid erosion and species loss. Whole ecosystems should be managed for more biological diversity. Some stands of old growth should be protected. We still have some small areas of virgin forest where trees such as large Liriodendron tulipifera grow. Private land owners should be encouraged to manage wisely and preserve streams, wildlife and habitat.

Herbicide use can be damaging to desirable species. Herbicides are best used selectively for eradication of certain very difficult pests such as kudzu, honeysuckle and poison ivy. When used indiscriminately under power lines they wipe out all the vegetation, including native azaleas, and can wash into waterways and cause more damage to animals and plants there. Cutting vegetation under power and telephone lines is a good alternative way of handling the problem of keeping the lines cleared. Native azaleas do quite well in these habitats. Cutting is better for the plants than applying herbicide to everything.

|

|

Road cut in mountains of North Carolina.

Photo by Sandra F. McDonald |

Road building is destructive to the plant and animal life in the environment, especially the cuts through the mountains. Very desirable plants, exposed along a newly constructed road, gradually disappear as a result of collecting and right-of-way maintenance. As an example, in 1999 we photographed a beautiful bright red plant of R. cumberlandense a short way up an abandoned road going off the new Cherohala Skyway. When the group returned to see the plant in 2000, it had already been stolen; only a hole remained.

|

|

Plant of

R. cumberlandense

photographed in 1999 had been

stolen by the time the Species Study Group returned in 2000 and found only a hole remaining. Photo by Don Hyatt |

Roads and power lines produce what ecologists call "edges," and too many edges will damage the ecology of an area. Some bird species like to nest on the edges of cut areas where they become more vulnerable to predators. Edges are also a threat to some other animals. Roads create more edges that favor weedy species and eliminate other species. Thinned edges allow more seeds to blow in than either intact forest or intact edges. Edges are best planted with native shrubs, vines and understory trees, and should have all non-native plants removed from them (Environment News Service January 29, 2001). Edges are not all bad, but there can be too many of them, and in wild places roads should be kept to a minimum. New road construction in these areas destroys habitat and creates more edges. Nature herself makes some edges by wind, floods, fire, and natural death of plants. One positive aspect of edges is that the native azaleas do bloom more heavily when they have sun from edge situations.

|

|

Large mining operation in the mountains.

Photo by Sandra F. McDonald |

Mining operations cause damage as the landscape is denuded. Even subsequent reclamation of high wall mining is problematic because the reclaimed site will be in grass for many years before the natural vegetation will come back.

Forest fires appear destructive to vegetation and burn rhododendrons, trees and other plants, but many of the rhododendrons regenerate from the base.

We should use care in importing exotics. Importing invasive plants, insects and diseases is dangerous. In the South the imported kudzu vine smothers out native vegetation along roadways, in national parks, on farms and in the landscape. Trying to keep it in check is very expensive. Kudzu eradication has a high priority in the parks. Entry of exotics like kudzu, gypsy moth, woolly adelgid, and lythrum needs to be prevented. In some cases plant breeding can be used to breed plants resistant to the exotic pests. Materials to be imported should be fumigated at points of foreign origin. We need to be sure the garden non-natives you plant are not invasive.

We should be wary of altering ecosystems. A prime example of ecosystem alteration can be seen today with the large deer population. Numbers of wolves and coyotes, the natural predators of deer, have been greatly diminished. Deer are now encroaching on man's living area. Unchecked deer population can leave a barren "moonscape" where everything is eaten except the large trees. All the plants and animals that were in the area are gone in these extreme cases. We need to keep biodiversity and be wary of removing links in the chain of life in the ecosystem.

State parks, national parks, and national forests are likely the last refuges for our eastern native azaleas. We should learn the locations of the natives in parks and inform park rangers and personnel of locations to prevent the accidental destruction of the plants. We can work to get sensible policies on visitation, encouraging using the parks in sensible ways that protect our native species and preventing destruction in the parks. We can volunteer to repair eroded trails and educate the public on the value of parks. We can institute policies to keep people away from fragile areas and deemphasize auto use in the parks.

We can work to restore and protect devastated areas. We can support the parks and land trusts such as the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy, The Nature Conservancy, Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation, Foothills Land Conservancy, Western Virginia Land Trust and Trust for Appalachian Trail Lands.

Things we as individuals can do to preserve our eastern native azaleas and rhododendrons for future generations include doing many things we have probably heard before and may already be doing. We can be energy conscious when using fossil fuels. We can use integrated pest management and least toxic chemicals at home. We can recycle more and waste less. We can be conscious of our impact on the environment. We can rescue natives from development sites by working with federal and state agencies, developers, and local native plant societies, and put these rescued plants into parks. We can propagate, grow and distribute the natives.

A preliminary estimate by The Nature Conservancy and the Association for Biodiversity Information in Arlington, Virginia, indicates at least a third of the nation's species should arouse conservation concern.

"The good news is Americans enjoy an incredibly rich natural heritage, from rare fish surviving in desert oases, to the world's tallest trees - California's coastal redwoods- to Hawaii's honeycreepers, colorful birds whose evolutionary story rivals that of the famous Darwin's finches, noted Bruce Stein, lead author of Precious Heritage - the Status of Biodiversity in the United States. "The bad news is that Americans risk losing much of the wealth if current trends continue" (The Nature Conservancy 2000).

References

Environment News Service: January 22, 2001. Evidence of rapid global warming accepted by 99 nations.

Environmental News Service: AmeriScan: January 29, 2001. Keeping invasive plants out of forest fragments.

Karl, T. R., R. W. Knight and B. Baker. 2000. The record breaking global temperatures of 1997 and 1998: evidence for an increase in global warming? Geophys. Res. Lett. Vol 27, No. 5, p 719.

Kron, K. A. 1993. A revision of Rhododendron section Pentanthera. Edinb. J. Bot. 50(3): 249-364.

Kron, K. A. 1995. A revision of Rhododendron VI. subgenus Pentanthera (sections Sciadorhodion, Rhodora and Viscidula). Edinb. J. Bot. 52(1): 1-54.

Kron, K. A. and M. Creel. 1999. A new species of deciduous azalea (Rhododendron section Pentanthera; Ericaceae) from South Carolina. Novon. 9: 377-380.

Laughlin, Jennifer B. 1991. Roan Mountain: a Passage of Time. Tennessee: The Overmountain Press. pp 124-135.

Nash, Steve. 1999. Blue Ridge 2020: An Owner's Manual. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press. 221 pp.

Nature Conservancy, The. March 16, 2000. The Nature Conservancy announces release of "Precious Heritage." Press Release.

Pimm, Stuart L., Gareth J. Russell, John L. Gittleman and Thomas M. Brooks. 1995. The future of biodiversity. Science 269 (July 21, 1995): 34750.

Wuethrich, Bernice. 2000. When permafrost isn't. Smithsonian Magazine. Feb. 2000: 32-33.

Sandra McDonald, a member of the Middle Atlantic Chapter, authored the article "Native Azaleas of Georgia" (JARS 46:3:146) and co-authored the article "Magic on the Mountain: An Azalea Heaven on Gregory Bald" (JARS 50:2:90) for the Journal.