Is This A Rock Garden, or What?

Clarence Barrett

Eugene, Oregon

I now can easily identify a rock garden: boulders mostly buried beneath the ground and artfully arranged so as to mimic natural outcroppings, spaces between filled with annuals, perennials and low growing shrubs, hopefully with a babbling watercourse meandering down the gentle slope to plunge eventually into a carp-filled, kidney-shaped pond or picturesque stream, bordered by overhanging willows and occupied by water lilies and ducks, real or ornamental. That is almost exactly what Elaine and I saw on our delightful visit to the famous rock garden at Windsor Great Park in England a year or so ago. It was so beautiful and so fulfilling and it is without a doubt what rock gardens should be, particularly if you have available a staff of fifty or so gardeners to look after it.

But what about the ordinary Joe with only an acre so so available, a limited budget and only a vague idea as to what a rock garden should look like, yet with hundreds of rhododendrons and a fortuitous supply of big rocks? Now that is reality, and here is how it happened.

Elaine and I had a wonderful rhododendron garden in the Coast Range mountains about thirty-five miles west of Eugene, Oregon. It was in a 50-acre Douglas fir forest, on the banks of a mountain stream, and the soil was deep and well drained so the rhododendrons and companion plants grew prodigiously, many to a height and girth of 12 feet (3.6 m) or more. Seven years ago along came a timber company with a full purse and a thirst for more trees, and with an offer we just couldn't refuse. Besides, Elaine was still working and was tired of the thirty five-mile commute over sometimes icy mountain roads. Her mother had just passed away and left a small tract of land on a mountain overlooking, dramatically, Eugene and Springfield and the Willamette and McKenzie valleys. We bought it.

To build a new home on the place, it being a hillside, it was necessary to excavate and level a portion of the site, to a depth of about 16 feet (4.8 m) on the high side. Unfortunately at 4 feet (1.2 m) the excavator hit solid rock. Now, it happened that he also operated a rock quarry, so he brought in his pneumatic drilling equipment and boxes of dynamite and proceeded to do the leveling. This produced boulders, lots of boulders, from gallon size to Volkswagen size, and the contractor inquired as to just how we were going to get rid of all those boulders, and there was a mountain of them piled alongside the building site. Thinks I, "Well, now, since we don't have much shade on this here homestead, how about using boulders for shade, at least for the time being, and until we can get some shady things growing." You see, we had brought along about 500 rhododendrons, mostly fairly small, but a few 6 feet (1.8 m) or so.

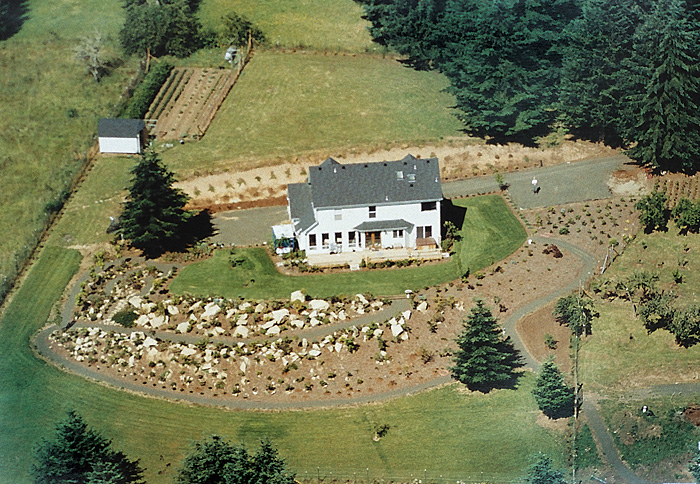

To plant the hillside with any order, and to facilitate mulching, watering and weeding, it seemed propitious to create some terraces. With a few passes with his bulldozer the contractor did that. But how to get the boulders arranged on those terraces? He thought of that also. He used a gigantic backhoe with a sort of thumb below the bucket, with which he could smartly grasp the largest of the rocks and swing it wherever asked and plant it skillfully and deftly, just as one might do with a 10-pound rock in one's bare hands. The end result was as pictured below, which is an aerial view of the terraces just after planting was completed.

|

|

Aerial view of property just after planting.

Photo by Clarence Barrett |

The rocks were just out of the ground, of course, and therefore were without moss or lichens or the patina that only exposure can supply, but with time these are forthcoming. While there are some boulders that were partly or fully buried in the soil, most were left almost totally exposed. Alas, I thereby apparently violated the first rule of good rock gardening: I didn't bury most of the rocks to make them appear to be a natural outcropping. I then didn't know the cardinal rules of rock garden construction. In my ignorance, instead of a rock garden I had constructed a garden of rocks.

In defense, I insist that rocks themselves, when properly arranged, have a beauty of their own, aside from their function as a foil for plants and means of drainage and source of cool root runs. And you know, now that the rhododendrons have had about seven years to grow we are not at all sorry for the arrangement. It is a great pleasure to watch as they twine themselves around the great boulders, or as tiny dwarf plants, like the waxy, scarlet Rhododendron 'Little Ben', enjoy the rock chips that erosion gradually brings down upon their heads. Some of the giant hostas (probably Hosta plantaginea ) forcing their way between great rocks are overshadowed by usually ground hugging dwarfs R. williamsianum , degronianum ssp. yakushimanum , roxieanum var. oreonastes , and various dwarf hybrids grown as standards on 6-foot (1.8 m) root stocks. When in bloom they form great snowballs, white, pink or red, 2 to 3 feet (0.6-0.9 m) in diameter.

Cascading down the side of one giant boulder is a weeping Norway spruce ( Picea abies ), with cones a foot long, and overhanging another is a weeping Japanese black pine ( Pinus thunbergiana ), in its contortion shading a tiny hybrids of Rhododendron degronianum . A nearby rock the size of a refrigerator is almost covered by Sedum oreganum 'Cape Blanco'. Scattered throughout the garden are rhododendrons with blooms of many hues, providing a kaleidoscope of color from mid-April through May and into June. On the south end of the garden shade was particularly needed to protect some tender rhododendrons from the midsummer heat. Three Magnolia grandiflora trees and three coast pines ( Pinus contorta ) were planted and seemed then so pitifully insignificant, but they have now grown to serve their purpose admirably.

On one gentle slope is a gorgeous thread leaf maple ( Acer palmatum dissectum ) over fifty yeas old, only 30 inches (75 cm) tall but with an 8-foot (2.4 m) spread, apple green in the spring and brilliant scarlet red in the fall. In being moved from the other garden it was badly broken but has come back with a passion. Peeking from beneath a great boulder is a colony of Cornus canadensis with its unbelievably realistic white dogwood blooms on such a miniature. Spreading beneath several rhododendron standards are groupings of Japanese iris ( Iris kaempferi ) in white, yellow and blue. Daring to show itself under the overhang of another great rock is the difficult Kalmiopsis leachiana , still clinging to life after a seven-year struggle, but blooming each year with its tiny pink flowers. One of my all-time favorites is Lewisia , which is native to this part of the world and is readily available, so we have lots of them in many forms and colors. Several clusters of dwarf iris of unknown genesis provide color during the summer and fall when the rhododendrons are resting, and a boundary of over forty taller, named hybrid bearded iris divide the lower rhododendron beds from an extensive lawn area. Framing our magnificent view of the cities and valleys are two very tall columnar Koster oaks ( Quercus ?), one at each end of the garden.

We've missed the sound of running water, which we had in such abundance at the other garden, so a couple of years ago I was inspired to create a watercourse. It arises beneath a huge rock at the top of our terraces, as if from a natural spring, and courses down across walkways beneath newly constructed bridges, down terraces to a small but noisy waterfall, then into a pond at the bottom. Along the sides are hostas and other shade and moisture loving plants, various overhanging dogwood trees ( Cornus florida ), a vine maple and some larger growing rhododendrons and deciduous azaleas. The dogwoods are beautiful but perhaps were a mistake in this application since they shed their leaves in the fall and literally clog the waterway. Perhaps it's worth the effort required to clean the channel each year. We've yet to put fish in the pond as we have a natural menagerie of opossums and raccoons that love them. They are quite bold and are rather fun to watch as they steal cat and dog food from the deck in front of the house, but we've decided not to augment their diet with fish.

Whatever its proper designation, rock garden or just a garden with a lot of big rocks, we enjoy our garden immensely, including its challenges and sometimes its seeming temperament. For instance, we recently had our well water tested and discovered that the pH is 8.5, far from the acid conditions that rhododendrons require, which may explain why we have been losing a few of that species. Fortunately it will be possible to secure equipment to inject acid into the water supply, thus solving that problem.

There's nothing very exotic in our garden; it contains mostly pretty ordinary things. But it's beauty we're after, not a botanical array or architectural perfection. The photos on below show the garden pretty much as it appears today. It's looking pretty good now. Recently I've gotten the conventional rock garden bug and have been building free standing basalt stone beds and purchasing a few more traditional rock garden plants to accompany the dwarf rhododendrons. It's amazing how they complement each other.

|

|

|

|

Red, pink and white dogwoods with R. 'Crest' (yellow)

and azalea 'Rosebud' in the foreground. Photo by Clarence Barrett |

Artificial spring.

Photo by Clarence Barrett |

|

|

Upper terrace with standard

R. williamsianum

.

Photo by Clarence Barrett |

It's a lot of work, but, what the heck, I'm learning a lot and I need the exercise.

Clarence Barrett is a member of the Eugene Chapter. His article "How To Create A Standard" appeared in JARS 46:4.