Rhododendron colemanii: A Detective Story

Ron Miller

Pensacola, Florida

Steve Yeatts

Athens, Georgia

Cast of Characters

This is the story of how a new tetraploid azalea from the Southeast was discovered by a motley group of plant hunters who, with a great deal of luck, came together to find a species overlooked for many years.

1

Our chance encounters and gifts differing just happen to have meshed at the right times, making it more than mere courtesy to say that, without any one of the following, the quest would have failed: Alvin Diamond, Buddy Lee, Ron Miller, R. O. Smitherman, Bob Stevens, John Thornton, Clarence Towe, Steve Yeatts.

The Mystery

It's not as if no one noticed the Red Hills azalea. Back in the 1940s or '50s or early '60s, S. D. Coleman, Sr., came upon a handsome, May-blooming, pink-flowered azalea, probably somewhere near Ft. Gaines, GA. He called it "Maypink." Out of historical habit, our group has done so itself until recently, though the name is deceptive - two-thirds of the plants in the wild are not pink - and the title is easily confused with "Maywhite," a synonym for

Rhododendron eastmanii

, with which this azalea has little in common, except in being confused with

R. alabamense

. We propose the common name "Red Hills azalea" because the plant is apparently confined to the Red Hills regions in Alabama and Georgia and perhaps Mississippi. For the botanical name, "Rhododendron colemanii" seemed inevitable from the start.

Whether Coleman noticed that his "Maypink" was always accompanied by a white, yellow-blotched form blooming at the same time, we do not know. We do know that he and his son propagated both the pink and the white forms and sold them to individuals at their nursery. They also distributed the azaleas to institutions such as the University of Georgia arboretum and Connecticut College and Callaway Gardens. The single University of Georgia plant is tagged "

R. arborescens

/Coleman's May Pink." That mistake is at least original. Callaway's numerous plants are today exceedingly large, perhaps as large as any deciduous azaleas in the country. They were labeled "

“R. alabamense

X

R. canescens

."

Mistaken Identities

Thus began a confusion persisting to this day. Although the plant is quite unlike

Rhododendron alabamense

in form and habitat, its odor is vaguely reminiscent, rather sweetish, somewhat musky - if lemony, then more like lemons themselves than like

R. alabamense's

Lemon Pledge, as one of our group describes it. Though the more common white form often has larger flowers than ordinary

R. alabamense

, a flower truss or a photo taken out of environmental context can at first glance be indistinguishable from one of true

R. alabamense

. The pink form can easily be passed off as a hybrid with

R. canescens

, yet in places like northern and central Alabama, where

R. canescens

and

R. alabamense

do in fact interbreed, the hybrids have none of the stature or the flower variety of the Red Hills azalea. And they bloom marginally earlier than

R. alabamense

, not almost a month later, as does

R. colemanii

(see Figs. 1, 2 and 3). The telltale distinctions, which apparently eluded earlier collectors, are listed in the table of comparison (Table 2) in the accompanying taxonomic article, Zhou et al. See Figure 4 of that article for photos of a typical flower, flower bud, capsule, leaf shape, and plant form; and Figure 5 for a distribution map of these two azaleas in the Alabama-Georgia Coastal Plain.

|

|

Fig. 1.

R. alabamense

, Clarke Co., AL.

Photo by Ron Miller |

|

|

|

|

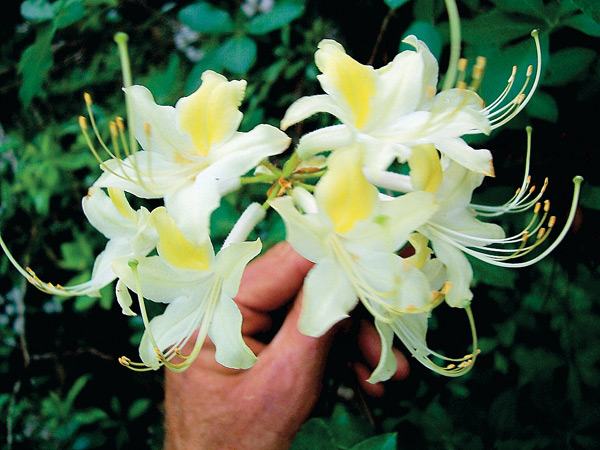

Fig. 2.

R. colemanii

, Monroe Co., AL.

Photo by Ron Miller |

Fig. 3.

R. colemanii

, Quitman Co., GA.

Photo by Ron Miller |

The parallel confusion of Rhododendron eastmanii with R. alabamense illustrates how easily a white, blotched Southern azalea can be passed off for years as a more well known azalea. The temptation has been even greater with the Red Hills azalea. At least R. alabamense does not extend east into South Carolina, where R. eastmanii grows. But the ranges of the southern form of R. alabamense and of R. colemanii both follow the curve of the Coastal Zone strata laid down during the Eocene, Paleocene, and Cretaceous geological periods, the incised country called the "Red Hills," stretching from SE Mississippi to the Chattahoochee River area of Georgia. We still do not know for certain whether the plant occurs in Mississippi. It should be sought there, since an "R. alabamense" is reported from the area where the Eocene Tallahatta Formation curves up toward Meridian. It may stretch, like R. alabamense and red clay, into Florida near Tallahassee and might even be discovered in the east above the Fall Line in the piedmont. 2 In short, any record of Coastal Plain R. alabamense in any herbarium or arboretum or on any map is at least suspect, as are many individual plants in private collections. A survey of the Auburn University herbarium revealed a number of sheets of evident Red Hills azalea, from the bloom date if nothing else, labeled either " Rhododendron alabamense " or " R. alabamense X R. canescens " or " R. alabamense X R. austrinum ." The University of Georgia herbarium has only one - a lucky miscue that proved to be crucial to our detective story.

Early Sleuthing

In his account of his meeting with Coleman, the great azalea hunter Henry Skinner never mentions a "Maypink." Perhaps Coleman found his plants after 1951. He and Coleman apparently pursued across the Lower South a short, May-blooming white azalea which, Skinner mused, ought to be named for Coleman. Being short and white, it was certainly not the Red Hills azalea but probably some Coastal Plain form of

Rhododendron viscosum

. Skinner also reported finding what he took to be complex

R. canescens-alabamense-austrinum

swarms in southern Alabama. Whether some of these were Red Hills azaleas, we cannot tell. Perhaps a few. At least one of his "hybrid" sites of proposed

R. canescens

and

R. austrinum

crosses with

R. alabamense

, both pink and yellow, does correspond to a solid

R. colemanii

location. Though occasional plants sometimes bloom in April, just as a few bloom as late as June, Skinner was busy crisscrossing the Atlantic tidewater during early May, when our azalea was at peak bloom in Alabama and Georgia. He certainly recognized that Southern azaleas often do not fit standard species and speculated rather obsessively on possible hybrid combinations.

3

That false identities can be hard to avoid can best be seen from the experience of two nurseryman-plant hunters, Buddy Lee and John Thornton, in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 1988, while looking in early May for

Rhododendron minus

along the Chattahoochee River - he and his colleagues had an ARS grant to do so - Thornton came across what he thought to be the most spectacular colony of

R. alabamense

that he had ever seen hanging over the water at a recreation site below Phenix City, AL. Lee and Thornton returned the next winter to take cuttings, which rooted nicely. (

R. alabamense

is rather touchy to root;

R. colemanii

is, along with

R. austrinum

and some varieties of

R. viscosum

, quite the easiest.) By chance, two years later, Thornton and Lee spotted some spectacularly tall and floriferous "

R. alabamense

" on a moist pine flat near Monroeville, AL. Again, they took cuttings. These were patently the same plant.

Some years later, after the naming of

Rhododendron eastmanii

, Thornton became uneasy because his plants were unlike the

R. alabamense

he had collected in the upland country north of Birmingham. They were too tall in the wild, too vigorous in the garden, and the flowers were off-color. So he sent a clipping to an academic azalea expert. Could this be the new species

R. eastmanii

? The brief answer came back quickly. The plant "keys out perfectly to Rhododendron alabamense." He therefore raised many plants from seeds and cuttings, selling them on highest authority as "Monroe County alabamense." They were even given away en masse at a Potomac ARS meeting. He sold two or three thousand more seedlings from his nursery. Red Hills azaleas are therefore today scattered all over the country under the guise of

R. alabamense

. Indeed, the reader may well own one. The Rhododendron Species Foundation at present offers this "R. alabamense" (their one photo for

R. alabamense

is of Thornton's

R. colemanii

4

), and the Seed Exchange has distributed Thornton's seeds.

Even earlier than this, in the late '70s, R. O. Smitherman discovered an odd patch of May-blooming azaleas along a road just north of Grove Hill, Clarke County, AL, in the far SW corner of the state. He saw very pink forms and white forms, which he thought might be different species. Carrying both forms back to the Auburn, AL, region, Smitherman began a breeding program with these plants, only to discover that the fragrance and general appearance of the Grove Hill plants were indistinguishable from those of "Maypinks" previously acquired from Coleman's nursery and from plants derived from Callaway Gardens later. The pink Coleman material, selfed, generated white and pink seedlings in a circa 2:1 ratio. Wild stock from Grove Hill led to interesting crosses with native azaleas and to fertile F1s with Exbury hybrids and with

R. austrinum

. Only at the very end of the search, when reliable ploidy data became available, did the import of these clues dawn upon us.

5

In the late '80s and early '90s, a young graduate student at Auburn, now Dr. Alvin Diamond of Troy University, combed the woods of SW Alabama as part of a project studying the Red Hills salamander. He spotted these late-blooming azaleas in several places and collected herbarium sheets. His notes on the sheets identified the plants as

Rhododendron alabamense

X

R. canescens

or

R. alabamense

or even

R. alabamense

X

R. austrinum

(as you will see from a later image, there are indeed yellowish forms of Red Hills azalea). These sheets were subsequently requested and studied by other botanists with no demurrals. Later on, Diamond became convinced that a separate taxon was involved, and he has been exceedingly helpful to the rest of us in locating new colonies. Without his directions to key sites, attempts to solve this problem would never have gotten off the ground.

New Evidence

In the middle 1990s, Bob Stevens and Steve Yeatts were directed to a site of a "Rhododendron alabamense" near Owassa, Conecuh County, AL, by a herbarium sheet at the University of Georgia. The colony was scattered along a Tallahatta Formation claystone ridge at the kalmia-pineywoods ecotone. They took cuttings and three years later had a blooming plant. Stevens had had long experience surveying soils in north Alabama

R. alabamense

country, and this Conecuh County plant just did not seem like the standard species that he knew so well. Could this be something with

R. viscosum

in it? In the end, he and Yeatts decided that the plant might be

R. eastmanii

. Several years later, the foremost hunter of

R. eastmanii

, Dr. Charles Horn of Newberry College, visited the site and declared that, whatever the plant might be, it is not

R. eastmanii

. For one thing, the odor is wrong.

6

Stevens and Yeatts recalled an article written by Thornton in which his large "Rhododendron alabamense" from Monroe County was discussed. They contacted him in the later '90s; directions were given. Visiting that site, they found that the large plants described had been destroyed by clear-cutting. They did find one small remnant population a few miles away on a semi-dry site; these plants were obviously the same as the plants near Owassa. They had also heard about the Grove Hill colony discovered by Smitherman, but that colony had succumbed to road building. Though the trail kept getting cold, Stevens and Yeatts became persuaded that an azalea, quite different from

R. alabamense

, inhabited SW Alabama.

Yeatts made it a mission to find out exactly what this southern Alabama plant was. A few years later, he was introduced by Thornton to Ron Miller, from relatively nearby Pensacola. When Yeatts told Miller that something odd was going on in southern Alabama with purported

Rhododendron alabamense

, Miller vaguely recalled seeing May-blooming "R. alabamense" along the sides of the roads in that region. Yeatts also passed on the location of the Owassa colony to Miller, who examined that colony while it was in bloom during May of 2005. Miller noticed the extraordinary mat of small runners around some water-starved plants; he had never seen

R. alabamense

, even at its most stoloniferous, behave in that manner (see Fig. 4). Our group learned later that Red Hills azaleas live by preference on the banks and ridges above water and often scatter outliers into drier areas. Stressed and over-mature plants send out mats of runners. A few of the giant Callaway plants are accompanied by such ground covers. Although healthy, large plants in moist environments send out at most a few offsets, almost every extensive colony reveals one or more of these mats, which provide a handy diagnostic tool at non-blooming times.

R. canescens

, the most frequent azalea in Coastal mesic sites, never sends out stolons.

|

|

Fig. 4. Mat of

R. colemanii

runners, Conecuh Co., AL.

Photo by Ron Miller |

These atypical colonies set back the hunt for many months, since we kept looking for additional colonies on semi-dry slopes. The breakthrough came when Diamond offered directions to an easy site along a creek in Butler County, AL. The next year Miller checked out the Owassa colony and then drove immediately to Diamond's creekside colony, which was in an identical stage of bloom - though with both pink and white flowers. (The Owassa colony is likewise atypical in having only a few pink-tinged plants.) The plants, often huge, were hanging over creek banks. They grew just above the

Rhododendron canescens

along the watercourses but could easily be separated by the bloomed-out piedmont azalea's dull, rust-colored, hirsute stems and rough leaves. Stems from the current year's growth on Red Hills azaleas are a characteristic light cinnamon brown, not hairless but sufficiently so for the stems to seem semi-glossy in the light.

R. canescens

leaves are most often elongated; Red Hills azalea leaves are relatively smooth and definitely ovate, with cuneate bases, except on very vigorous shoots. Some plants have smooth, thin, dull leaves resembling those of

R. alabamense

; others have leaves that are darker green, shiny, and almost coriaceous. A ready way to distinguish these azaleas is to find a flower bud.

R colemanii

buds are smooth and linearly tapered, with thin, uneven, brownish edges on the scales in the winter that are not nearly so distinct as the sharp chocolate edges of the bud scales of

R. alabamense

.

R canescens

buds are without brown rims, often rosy, blunter, sometimes knobby. If there are green seed capsules, the game is easier still. Almost all fresh

R. colemanii

capsules are unique among those of the sympatric species in having gland-tipped hairs visible with a jeweler's loupe on the calyx area and on the petiole.

7

In any case, the Butler County colony was a revelation for Miller: "So that's where these plants live!" Where had he seen a similar location? Not at the specific Monroe County, AL, site where Lee and Thornton discovered their plants, but near their site, on an overflow watercourse several hundred yards north of a creek, where he had noticed late-blooming pink (uh, pink?) "Alabama azaleas" for 30 years while driving in May to a camping spot along the Alabama River. This clue was strengthened because one month before, he had taken Thornton to a site for true, April-blooming

Rhododendron alabamense

across the Alabama River, just to the west in Clarke County; and Thornton had looked at those dry land plants and declared, “These aren't my Monroe County

alabamense

.” But they were classic

R. alabamense

, gangly plants up to 20 feet tall, perhaps, but unmistakable

R. alabamense

. Putting these hints together, Miller drove to the site that he had motored by so often, pushed into the very dense waterside woods, and found a wonderland of white and pink and light yellow flowers. A call brought Yeatts and his associates to the site (see Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8).

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5.

R. colemanii

, Conecuh Co, AL.

Photo by Ron Miller |

Fig. 6.

R. colemanii

, Monroe Co., AL.

Photo by Ron Miller |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7. R. colemanii, Quitman Co., AL.

Photo by Ron Miller |

Fig. 8.

R. colemanii

, Monroe Co., AL.

Photo by Ron Miller |

Apprehending the Suspect

Finding more plants along the banks of the creek to the south, Miller then remembered that he had seen a landform almost identical to the one he was standing on. It was a creek bank in Georgia, above Georgetown, a fine

Rhododendron prunifolium

site. Since Thornton had found the azalea 20 miles north of that spot on the Chattahoochee River in Alabama, and since Coleman lived about 20 miles south, maybe... A few weeks later, he drove east 200 miles, parked his truck, and walked directly to the north-facing creek bank. Scattered among the plumleaf azaleas that he remembered so well were huge, obvious Red Hills azaleas with newly spent flowers. They had been there all along, right under our noses. We had probably leaned on them while admiring the plumleafs. Many additional sites were discovered during the remaining summer by the judicious use of topo maps and bug spray. Later during a winter foray, Yeatts demonstrated conclusively that

R. alabamense

and

R. colemanii

could be distinguished in the field not only by habitat but also by the flower buds. Red Hills winter flower buds are markedly larger and more tapered and less green toward the base of the scales. They look, Yeatts noted, more like the buds from

R. calendulaceum

. We were really getting to know this azalea.

Considering the consistently later time of bloom, the mesic sites, the plant form and behavior, the buds, and the wild variations of color, including yellow, we were confident that we had a separate taxon on our hands. The yellows were particularly revealing, since

Rhododendron austrinum

could not be found anywhere in those areas. But academic experts had pronounced the dominant white forms to be

R. alabamense

, and nothing was more inevitable than the time-worn dismissal of the pink and yellow groups as hybrid swarms containing that azalea. The variable color forms and flower shapes did not make our case easier, nor did the co-extensive ranges of the two plants. From a behavioral point of view, Red Hills azalea seemed unusually distinct, and its locations were downright predictable. In an area underlain by the proper geology, look along the base a steep north-facing slope above a stream or on a high sandy-ridged flat or bank along a waterway; and if there are other ericaceous plants nearby, Red Hills azaleas are likely to appear - if not there, then 200 yards in either direction through the brush and the snakes and the smilax. No permanent water nearby, no plants. Nonetheless, in the past, a scheme of classification based on dried material and botanical keys had successfully obscured that which had now become so glaringly obvious to us in the field.

During May of 2007, Thornton and Miller undertook a lightning tour of sites found the previous year. The major unresolved issues were (a) whether the colonies in bloom seem uniform across the range, and (b) whether the plant crosses over onto the piedmont in the north. Thornton's experience of over 15 years growing seedlings commercially offered strong evidence that the plant was no hybrid, since there was no reversion to accepted species among the thousands of plants and since the standard color mix of two parts white and one part pink or pinkish seemed to hold. In the field, colonies from Monroeville to Phenix City, with the exception of the oddball Owassa colony, occupied similar sites, showed similar plant forms, and revealed a stable color balance across the board. The two tourists briefly surveyed regions near Columbus, GA, and north of Montgomery, AL, but found no

R. colemanii

on the piedmont. On the same trip, Thornton and Miller detoured to visit

R. eastmanii

colonies in South Carolina in order to assure themselves that the behaviors and forms and habitats of the two May-blooming pseudo-alabamense were different. They most definitely were. Even Clarence Towe, our resident Devil's Advocate, at last conceded that we had a species - but would anyone who had not accompanied us into the field believe us? Could we count enough hairs and glands or measure enough flowers and leaves and petioles to make the case?

The Verdict

At this point, molecular biology came to the rescue, like a surprise witness in a "Perry Mason" show. Towe had a previous contact with Dr. Ben Hall of the University of Washington. Hall generously agreed to run DNA sequences for five Red Hills azalea branch tips across the range of the species, from SW Alabama to the Chattahoochee River region. The source plants were selected to include yellow forms and pink and white. Also submitted were five branch tips of

Rhododendron alabamense

from SW Alabama to northern Alabama to the Chattahoochee River to Leon County, Florida. In a surprisingly few days, Hall emailed back that

R. colemanii

is a member of what is now labeled clade A of Pentanthera, a kinsman of

R. austrinum

and

R. calendulaceum

and far from

R. alabamense

and

R. canescens

. The samples of both species showed variations of the sort to be expected within a stable species, and the two plants were quite as well separated from each other as any two azaleas could be.

8

The "hybrid" charge and the "alabamense" confusion were both suddenly laid to rest, with the additional assurance that

R. alabamense

is indeed a coherent species across north and south Alabama. From the great variations in plant size, we had always felt uneasy about the latter species.

In a stroke of amazing luck, Towe had just received, second-hand, a draft of a revolutionary article on rhododendron ploidy, read it, and mailed it next to Miller. According to flow cytometric work by Dr. Tom Ranney of NC State and associates, all the other Southeastern

Pentanthera

listed in what is now Hall's clade A are tetraploid.

9

The immediate inference from Hall's email was that Red Hills azalea would turn out to be tetraploid, too. Several of us had guessed as much for years, considering the heftiness of the stems and leaves and the opacity of the flowers (a contrast quite visible in the photos of the two white flowers in Figs. 1 and 2, above). Polyploidy would be the icing on the cake. Since

R. alabamense

is a diploid and

R. canescens

a diploid, then a tetraploid Red Hills azalea must be a separate taxon, q.e.d... Ranney and Hall were quickly acquainted with the link between one another's work, and a week or two later, Towe visited Ranney at his lab, carrying with him samples from across the range of our azalea, including a few leaves filched from a Callaway Gardens plant as a nod toward Coleman himself. Before Towe left Ranney's lab in Fletcher, NC, the results came back:

R. colemanii

is in fact a tetraploid.

10

Elementary, my dear Skinner.

Reflections on the Case

No doubt it has been great fun to find a new species beneath our noses and to confirm its uniqueness using new molecular methods. Just when these new-found methods were opening up a brave new world for taxonomy, our group had the good fortune to be in the right place with the right connections. How easily Hall and Ranney might have dismissed us all as rank amateurs, unworthy of their professional attention. No less delightful was providing, as a lagniappe, an important keystone for the phylogenetic restructuring of the

Pentanthera

.

However, in looking back at this yarn, it seems inescapable that something is fundamentally flawed about our taxonomic protocols - our traditional ways of collecting, storing, and analyzing data on plants - when it took the almost miraculous intervention of gene sequencing and flow cytometry at this late date to bring into sharp focus an azalea that is not uncommon, often spectacular, and quite distinct in the field. The populations were out there all along, being tripped over by botanists, competing with evergreen shrubs, and evolving forms and behaviors to deal with that distinct environment. Yet somehow, mummified on those herbarium sheets, they did not "key out" into visibility. There is an old story about an Athenian selling his house who carried a brick from the building around as a sample for buyers. The Greeks understood this ploy to be a broad jest; our traditional taxonomic methodologies would surely have bought the house, sight/site unseen.

Red Hills azalea is a handsome and, in due time, exceedingly large species; and selected clones are of considerable horticultural interest, as some of the photos in this article surely attest. Finding another polyploid azalea is likely to have profound implications for the study of the evolution of our native

Pentanthera

. The fact that Red Hills azalea is a tetraploid comprising such variations suggests that it should provide a wealth of fertile heat-tolerant hybrids with Exbury hybrids and with other Southeastern tetraploids such as

Rhododendron austrinum

,

R. atlanticum

, and

R. calendulaceum

. Our final photo is of a cross between a white Red Hills azalea and the Exbury 'Gibraltar.' Such possibilities are -- well - interesting (see Fig 9).

|

|

Fig. 9. R. O. Smitherman’s 'Patsy's Pink'

( R. colemanii X 'Gibraltar'). Photo by R.O. Smitherman |

Endnotes

1

Zhou, Wenyu, and Taylor Gibbons, Loretta Goetsch, Benjamin Hall, Thomas Ranney, and Ron Miller, "

Rhododendron colemanii

: A New Species of Deciduous Azalea (

Rhododendron

section

Pentanthera

; Ericaceae) from the Coastal Plain of Alabama and Georgia."

JARS

62, No. 2 (2008):72-78

2

See the Mississippi county map for

Rhododendron alabamense

on the USDA Plants Database, (http://plants.usda.gov/index.html). We have recently received excellent evidence, yet unconfirmed, of

R. colemanii

in Clarke County, MS, in an area underlain by Eocene strata.

R. colemanii

has been located 21 miles from the Florida border in Georgia.

3

Henry T. Skinner, "In Search of Native Azaleas,"

Morris Arboretum Bulletin

6 Nos. 1-2 (1955), rpt. University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center

4

See the Rhododendron Species Foundation photo listing for

R. alabamense

5

Jones, J.R., T.G. Ranney, N.P. Lynch, and S.L. Krebs, "Ploidy Levels and Relative Genome Sizes of Diverse Species, Hybrids and Cultivars of Rhododendron,"

JARS

61, No. 4 (2007):220-227.

6

Charles Horn, Personal Email to Miller, Feb 24, 2007.

7

Unfortunately, these glandular hairs are usually lost on dry, well-handled herbarium specimens. The pinhead hairs are visible, particularly on the edges, on the photo of the typical capsule on the composite illustration, Figure 4 in Zhou et al.

8

Zhou et al., 72-78.

9

Jones et al.; Zhou et al., 72-78.

10

See Zhou et al., Table 2, for a listing of genome sizes of various azaleas, including

Rhododendron colemanii

,

R. canescens

,

R. alabamense

, and others.