Die a Graphic Death: Revisiting the Death of Genre with Graphic Novels, or “Why won’t you just die already?”

Graphic Novels and the Slow Death of Genre

In “The Death of Genre: Why the Best YA fiction Often Defies Classification” ( The ALAN Review , 35.1: 43-50), Scot Smith speaks of having to constantly reclassify and reshuffle texts as he and his students consider the books on the genre lists used in his classes. Knowing that “Young adult literature has a long tradition of authors whose works defy genre classification” (43), he mulls over the idea of creating a genre-busters category for “novels which do not easily fit into a single category” (43). He concludes his article by stating, “By denouncing genre, we may perhaps begin to expand the horizons of our adolescents” (49). As someone who travels the country speaking to pre-service teachers, in-service teachers, English professors and Education professors, about graphic novels, I sympathize with Scot as he grapples with the issue of genre, a term which he feels may need to be retired.

What I have found repeatedly is that, regardless of the conscientious scholars and creators who have written on the graphic novel as being a form beyond genre, many students, teachers, and professors continue to refer to sequential art narration (comic strips, comic books, and graphic novels) as a genre rather than, as I think is more accurate, a form or format. This haunts me. Class after class, event after event, I find myself feeling like the arch-nemesis who thought he had finally conquered an old foe once and for all, only to curse the heavens when the apparently super-powered terminology resurfaces: “Why won’t you just die, already!?!?” I extort. Or, in my more reflective moments, I may quip, “Haven’t I killed you already?” But no; I haven’t.

This article is an extension of my continued efforts to rid the world of the notion that the graphic novel is best thought of as a genre. Herein, I will offer alternative classifications, stating that we might best see the graphic novel as a form that supports multiple genres ; attempt to explain why genre is a reductivist term when it applies to sequential art narratives; and offer visual examples and ready-to-use activities to help illustrate my points.

Part I: Terminology with a Possibly Unpleasant Kick

Understanding Comics

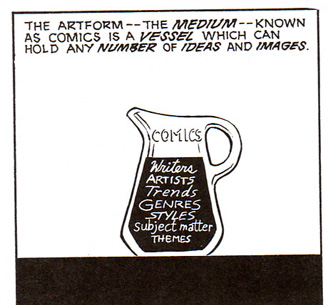

To be fair, I admit that I was once guilty of the sin of which I write. In my earliest days of researching comics and pedagogy, I too called graphic novels a genre, and I was far from alone. Then I read Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics and Will Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art and Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative, all texts from authors who actually create sequential art and teach it to others. McCloud refers to comics as an “artform—the medium— known as comics is like a vessel which can hold any number of ideas and images” (6). He uses form and medium interchangeably. For McCloud, comics consist of writers, artists, trends, genres, styles, subject matter, and themes (6). In this vessel, which McCloud visually portrays as a pitcher (see Figure 1), it is clear that genre is “subsumed” within the larger form.

This idea of form subsuming genre seems to run counter to how many literary-minded folks consider genre. For instance, in the classic A Reader’s Guide to Literary Terms, Karl Beckson and Arthur Ganz state that genre is:

A literary type or class. Works are sometimes classified by subject—thus carpe diem poems ( q.v. ) may be said to constitute a genre—but the more usual classification is by form and treatment. Some recognized genres are epic, tragedy, comedy, lyric, etc. From the Renaissance through the eighteenth century, the various genres were governed by sets of rules which a writer was expected to follow. Recently, however, criticism has become less directly prescriptive and less concerned with distinctions among genres, though they are still considered useful (67-68).

Beckson and Ganz appear to define genre and form as synonymous. But, as I look at their examples of recognized genres, I see that the epic is a type of oral narrative poem; tragedy and comedy are types of drama; and the lyric is a type of poem. For each genre listed, there is a larger form to which it belongs.

In the very-recent Genre Theory: Teaching, Writing, and Being, Deborah Dean illustrates how genre continues to trump form in some intellectual circles. Dean states that “Genres are more than forms,” furthering this claim herewith:

Although, as Anthony Pare and Graham Smart acknowledge, ‘repeated patterns in the structure, rhetorical moves, and style of texts are the most readily observable aspects of genre’ (147), these observable features do not, by themselves, constitute a genre. Aviva Freedman and Peter Medway explain that regularities in form come from the situation, instead of existing without reason: ‘Genres have come to be seen as typical ways of engaging rhetorically with recurring situations. The similarities in textual form and substance are seen as deriving from the similarity in the social action undertaken’ (“Introduction” 2). Bazerman extends the explanation, showing that forms not only come from situations but also guide us through situations: ‘Genres are not just forms. Genres are forms of life . . . Genres are the familiar places we can go to create intelligible communicative action with each other and the guideposts we use to explore the unfamiliar’ (“Life 19). And Marilyn L. Chapman affirms the others’ assertions about form’s relation to genre: ‘Rather than rules to be followed . . . or models to be imitated . . ., genres are now being thought of as cultural resources on which writers draw in the process of writing for particular purposes and in specific situations’ (469). So, although form is an aspect of genre, form does not define a genre. (Dean 9)

Less directly prescriptive, indeed. Each of the experts Dean quotes defines genre liberally, but each also extends the literary-minded ideal of form as part of genre, whereas the visual artists/theorists I’ve mentioned and I, too, would say, instead, “although genre is an aspect of form, genre does not define a form.” I will expound on this point shortly, but let us consider how the genre vs. form dilemma is playing out in recent publications on YA literature:

Perhaps it is thinking similar to Beckson and Ganz’s, and Dean’s and her admittedly impressive sources, or maybe it is the “newness” of the form—or the newness of considering the form as viable—that is contributing to the conundrum of exactly what and how to consider graphic novels. For example, in an early discussion of them in Young Adult Literature: Exploration, Evaluation, and Appreciation , Katherine Bucher and M. Lee Manning use both genre and format to describe comic books, graphic novels, and magazines. They state, “These formats differ dramatically from the genres that educators have traditionally encouraged adolescents to read” and “For many young adults, these three genres represent a welcome move away from what they consider traditional ‘school’ reading” (4). The chapter dealing with comics and graphic novels explicitly in their textbook is entitled “Exploring Other Formats” but refers to graphic novels as a “visual genre” (278). Bucher and Manning break down some popular comic book series under the headings super-heroes, humor, fantasy/science fiction , and manga . Despite the possible error of considering manga a genre instead of a form, as well, they touch on the fact that they are essentially offering their readers different genres of things that they themselves have described as genres.

This begs the question: If something can be subdivided into parts that are each extremely distinct, can we call that thing a genre? Surely there are subgenres, but if something can be a fantasy story, a romance, historical fiction, nonfiction, journalism, mythology, or a war story using the same format, can we truly call that form a genre? The term “sub-genre” suggests to me very fine degrees of separation from overarching themes, not formal elements of display or vast differences in themes and outlooks.

Again, though, I must not be too quick to judge folks for possible missteps. One of my most vivid memories of editing Building Literacy Connections with Graphic Novels: Page by Page, Panel by Panel involves a frantic e-mail and phone call to the editor once the book was about to go in the final stages of production. I realized that in my introduction, I had referred to the graphic novel as a genre rather than a format fourteen times. We caught what was, for me, and for the most part still is considered an error, but only at the last minute.

It is important to emphasize that the graphic novel is not solely situated in a print-based literary tradition, but in a fine arts-styled visual tradition, as well. Will Eisner, is considered an American master of the graphic novel, a term that he helped popularize by placing it on the cover of the paperback edition of his critically acclaimed A Contract With God and Other Stories (published in 1978) and legitimize by discussing it as a term that separated “literary” comics from the super-hero tales most often associated with the format. Eisner says in Comics and Sequential Art (first published in 1985), “The format of the comic book presents a montage of both word and image, and the reader is thus required to exercise both visual and verbal interpretive skills” (8). He quotes a Tom Wolf piece from 1977’s Harvard Educational Review that discusses how reading and literacy are terms that themselves are coming “under closer scrutiny . . . . Indeed, reading—in the most general sense—can be thought of as a form of perceptual activity. The reading of words is one manifestation of this activity; but there are many others—the reading of pictures, maps, circuit diagrams, musical notes . . .” (Eisner 8). Eisner is inspired by these lines to suggest, “In its most economical state, comics employ a series of repetitive images and recognizable symbols. When they are used again and again to convey similar ideas, they become a language—a literary form, if you will. And it is this disciplined application that creates the ‘grammar’ of Sequential Art” (8).

Therein I feel that Eisner may inadvertently articulate not only why we should see comics and graphic novels as forms rather than genres, but also why some may feel strongly about using the term genre over form or format . While Eisner’s words appeared a good fifteen years before The New London Group and Bill Copes and Mary Kalantzis were bringing the idea of visual and multimodal literacies to the English teacher’s consciousness, Eisner and others actually involved in the creation of visual texts were making strong intellectual arguments that were only being heard by those already interested in their chosen form of expression.

In Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative , Eisner joins McCloud in calling comics both an art form and a medium. On the term graphic novel , he says, “This last permutation [of the comic art form] has placed more demand for literary sophistication on the artist and writer than ever before” (Eisner 3). In saying the form was moving toward the more literary, Eisner is clearly implying that sequential art narration had once been squarely situated in the realm of the visual arts. The relatively recent phenomenon of teachers even considering graphic novels in their English language arts classes may further support his notion. I sometimes want to ask folks, “Do you remember when we used to value the visual arts so much in our schools that we actually had teachers who taught them in their own classes?” but, knowing that speaking it is one way by which we acknowledge the reality of it, that irks and depresses me for other reasons, so I let the question pass.

It does seem to me that English teachers have had and often still do have a tendency to exalt the written word as best text, regardless of the fact that words are simply a string of letters, and that letters are simply pictographic images or graphemes that have developed a privileged signification over time. Though accepting these premises lets us see that all reading is visual reading, that all literacy has some element of visual literacy (for those of us who are sighted, of course), many are still quick to separate and qualify works that have no visual arts-related texts to be read and interpreted from those that do have additional visual demands. Based on definitions of classification of genre, form, and medium from the likes of Beckson and Ganz, Dean, McCloud, and Eisner, and my experience as a teacher and teacher educator, my basic hypothesis is that educators with a literary background discover the graphic novel or comics and, like Eisner, see a consistency of formal elements from page to page or from one book to the next but take the Beckson and Ganz or Dean approach, mistaking the formal style of representation as elements of genre, not as elements of a larger form, or of a grammar or language as Eisner suggests. After all, when reading traditional literature, continued references to certain images or themes help define genre. But a particular brushstroke could be used in any number of variedgenre paintings.

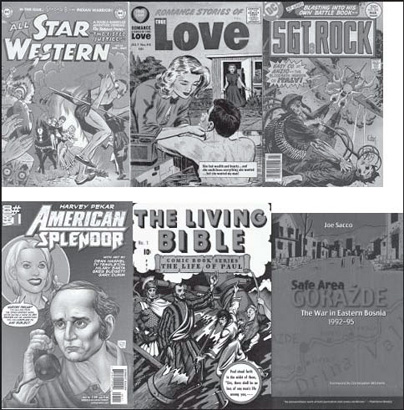

When we talk of the actual language used in traditional print texts, we do not identify the language itself as a genre. The words might help us consider the genre of the overall form in which they appear. For example, the highly stylized language and themes of Bram Stoker’s Dracula suggests that it is gothic in tone and theme. The overall formal layout of the letters and words lets us know the work is epistolary in form, and we know by considering the form as a whole that it is a novel. We know that it is a fiction novel because no one has ever been bitten by a bat and transformed into a vampire. In works that are even more visual in nature than those that use signified pictographs or graphemes, we can not confuse formal elements in repetition for indicators of genre—though, just to add to the mystification of the matter at hand, I should point out that Beckson and Ganz say of the epistolary novel, “The artificiality of the method . . . soon led to the devise of the genre as a popular form” (54). Instead, the formal elements, the panels, balloons, and borders, define the format. As Kenneth L. Doneslon and Alleen Pace Nilsen state in Literature for Today’s Young Adults , when it comes to works of sequential art narrative, “the term format is more accurate than genre because the stories range from science fiction and fantasy to mysteries, historical fiction, love stories, and whatever else a creative person might think of” (315), like, say, epics, comedies, tragedies, or lyrical poems. McCloud, Eisner, Donelson and Nilsen and others have helped me come to the conclusion that it is most accurate to consider comics book and graphic novels as forms of sequential art narrative, as formats or mediums, that support multiple genres. Consider Figure 2, which contains five comic books and one graphic novel, all works of sequential art narrative.

Figure 2. Multiple Genres Supported by the Sequential Art Form

Titles top-to-bottom, left-to right: 1. All Star Western #58. DC Comics, 1951; 2. Romance Stories of True Love #56; Publisher unknown, 1957; 3. Sgt. Rock # 302. DC Comics, 1977; 4. American Splendor #1 by Harvey Pekar and various artists. Vertigo, 2006; 5. The Living Bible #1. The Living Bible Corporation, c. 1945; 6. Safe Area Gorazde by Joe Sacco. Tandem, 2001.

Each of the cover images were obtained from The Grand Comic Book Database, available at http:// www.comics.org. They represent a western, a romance, a war comic, a slice-of-life comic, mythology/ historical fiction/historical nonfiction (depending on one’s belief system), and comics journalism. I could have easily found images for the super-hero, high fantasy, science fiction, fairy tale, horror, true crime, and mystery genres, as well. That much variety in supported genres surely illustrates that even the subgenre argument is a weak one when it comes to sequential art narratives. And reading these works would only reveal serendipitous similarities in themes and issues at best. What they share in common are formal elements, not genre elements.

Other prominent scholars have made the overt realization that form or format is a better term than genre when describing the graphic novel, as well. Teri Lesense has recently written that “graphic novels represent a completely new format in YA books” (67) and asserts, “The new YA literature differs in both form and substance. Graphic novels, for instance, combine text and illustration in new ways and are, therefore, a logical extension of the picture storybooks enjoyed by students in elementary schools” (63). While we have already herein considered the accuracy of the term “new” and Eisner and I would argue that the pictoral elements of graphic novels are not illustrative but as essentially textual as the print, and that the totality of the pictures and words form what I have elsewhere called conglomerate layers of text, Lesesne continues, “Stories that combine distinct genres in a seamless blend move beyond the confines of each genre to extend stories in new directions” (63). Lesesne seems cognizant that the graphic novel is something beyond genre and uses the term “format” explicitly. She also seems to understand that there are various genres of manga and refers to it as “a form of graphic novel” (64).

Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey prime their readers in the introduction to the collection Teaching Visual Literacy: Using Comic Books, Graphic Novels, Anime, Cartoons and more to Develop Comprehension and Thinking Skills by asking, “Do comic books and graphic novels constitute an appropriate genre for classroom instruction?” (2) in order for contributors to focus on the terms’ finer distinctions. Contributor Jacquelyn McTaggart informs, for example, that “Manga . . . is an art form” (Fisher & Frey 30) where students read stories “from back to front, but this format does not seem to confuse kids” and that

Today the term ‘comic book’ describes any format [her italics] that uses a combination of frames, words, and pictures to convey meaning and tell a story. Perhaps it will help us understand the distinction between the two if we remember that all graphic novels are comic books, but not all comic books are graphic novels [again, her italics]. Every publication that uses the format of frames surrounding text and graphics is considered a comic or comic book. The lengthy ones, referred to as graphic novels, are also comics (31).

It is a play on words to say that all graphic novels are comic books, a play that Eisner might not have approved, but it is accurate in so much as graphic novels are “books full of comic art.” In the same collection, I refer to “sequential art forms” to describe comics and graphic novels (47) and explicitly speak of “the comic book format” (49). Also in the same collection, Rocci Versaci agrees with McCloud and calls comics “a visual medium” (96). McTaggart, Versaci, and I have all previously and separately published on comics in the classroom, and Verscaci and I have each actually taught classes on comics as literature (I have even taught a class on graphic novels as YA literature). This illustrates that when someone asks a scholarteacher knowledgeable of sequential art if comics are a genre, they respond with talk of formats and mediums. Of course, I have found that there is still some resistance to considering someone who studies sequential art a true scholar, and perhaps this also contributes to teachers favoring traditional literary thoughts on genre, reincarnating the beast even as wellinformed others have sought to slay it. Peter Smagorinski seems to acknowledge the semantic soup we dip our spoons into when dealing with comics, genre, and format in Teaching English By Design . He states, “A genre refers to works that share codes: western, heroic journeys, detective stories, comedies of manner, and so one. These genres are often produced through a variety of media: short story, drama, novel, film, graphic novel, and so on, which themselves are referred to as genre” (120). He doesn’t expand this last bit of sentence to say whether he thinks that referencing is acceptable or not, but he does say “By genre, I do not [his italics] mean strictly form-oriented groupings of literature—poetry, drama, the novel, and other structures; these make a diffuse and unproductive means of organizing a curriculum” (120), sounding very much like me when a teacher asks what she should include in her thematic unit on graphic novels. I will usually offer suggestions but also urge the teacher to consider looking at the thematic units she is already doing and find graphic novels that might fit into them.

Counterpoint

Doug Fisher & Nancy Frey

Though they let their contributors take center stage in Teaching Visual Literacy: Using Comic Books, Graphic Novels, Anime and More to Develop Comprehension and Thinking Skills (2008), Doug Fisher and Nancy Frey know a little something about graphic novels and pedagogy themselves. They consistently use sequential art narration and techniques to teach their Hoover High School (San Diego, CA) students multiple literacy skills; they frequently present their work at national conferences, and they’ve published extensively on the intersections of sequential art and literacy. Indeed, their article “Using Graphic Novels, Anime, And The Internet In An Urban High School” won NCTE’s Kate and Paul Farmer award for outstanding essay in 2004.

I asked them why they sometimes use the term “genre” over “format.” The answer reveals that when it comes to defining terms, often the act of classification must match the given exigency:

“The word genre comes from the French (and originally Latin) word for ‘kind’ or ‘class’. There are no “rigid rules of inclusion and exclusion” (Gledhill1985, p. 60). ‘Genres . . . are not discrete systems, consisting of a fixed number of listable items’ (p. 64). As such, the term gets used at a more macro level (e.g., nonfiction) and then again at a more micro level (e.g., biography, memoir, science fiction). It also seems reasonable to consider graphic novels a genre as there are some very specific characteristics of graphic novels that differ from comics or anime, a la genre. But at the end of the day, our work focuses on encouraging teachers to use sequential art in their classrooms and if the familiar term ‘genre’ encourages secondary school English teachers to use these texts, then we’ll say it over and over again. “

Gledhill, C. (1985). Genre. In P. Cook (Ed.), The cinema book. London: British Film Institute.

As Smagorinski says, he finds the short story to be an odd way to group literature for studying because of its diverse forms and themes, so too do I see a unit on the graphic novel as odd because of the vitality and diversity of the genres the form supports. Smagorinski clarifies, “I use genre to refer to texts that employ a predictable, consistent set of codes” (120). As mentioned earlier, the predictable, consistent codes on graphic novels are format, not genre-based, so we must not consider one as the other. Yes, most comics and graphic novels will have panels on pages with word balloons and narration in each panel, the panels placed in sequence, and the expectation of readers that they know to follow the balloons and panels left to right, top to bottom (unless it is an unflipped manga, of course). But the codes of the characters and plots and visual elements found within each piece of sequential art narration will make the genre, not the shared form that supports those genres.

Smagorinski is fine with units of genre study, supports them, even, and I, too, find myself thinking it is acceptable to integrate graphic novels into such units when the study is overtly focused on genre itself. Surely, there are some excellent romance comics that could help illustrate the themes, trends, and tropes in romantic novels. Surely there are some horror comics that—if one can find panels acceptable to bring into school setting—can help illustrate red herrings, suspense techniques, and uncertainty. Dick Tracy and Batman could easily accompany works from Edgar Allan Poe and Gaston Leroux in considerations of mystery or detective fiction. However, as Smagorinski suggests, we want to make sure that units arranged by genre have the proper types of codes in common.

Part II: From Terms to Texts

Now, there is more to the death of genre as it relates to graphic novels, of course. Smith’s article is not about distinctions among terms so much as it is about distinctions among texts. His troubles with genre stem from the fact that so many great young adult novels are jumping genres. This is true for graphic novels, or more appropriately used in this case, sequential art narration, and for other less traditionally print-text works, as well. Consider Brian Selznick’s The Invention of Hugo Cabret , a story that combines traditional novel narration with storybook and wordless graphic novel (novels can be graphic novels without the letters) and draws its inspiration largely from film. Walter Dean Meyers has often integrated visuals into his novels. Monster is a prime example, and The Autobiography of My Dead Brother uses sequential art narrative not just to illustrate but to tell and reinforce the importance of its plot elements. Though not using sequential art per se, the reliance on visual images as text in novels like Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and Lauren Myracle’s IM-inspired novels like l8r g8r and ttfn is so great that the book would not be the same, could not tell the same story, without them. Jerry Spinelli even reminded us of the power of the visual as text by using pictographic icons instead of iconically pictographic words on the cover of his book Star Girl . In mainstream publishing, as well, sequential art is being integrated into novels and shelf space more and more. Consider Jodi Picoult, who recently wrote a story arc for the comic book series Wonder Woman and who has a character share his Infernoinspired comics in her novel The Tenth Circle (2004). Even when novelists do not use sequential art or comics in their novels as means of expression, more and more of them are writing about or using themes associated with particular genres of sequential art, especially the super-hero genre. Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay , Austin Grossman’s Soon I Will Be Invincible , and Jenifer Estep’s Karma Girl are mainstream novels that pull from super-hero mythos, as do young adult novels Hero by Perry Moore and TK, and Barry Lyga’s The Astonishing Adventures of Fanboy and Goth Girl .

Further, there are comics and graphic novels that act as exemplars of their particular genres. Runaways is a an excellent series of comics and graphic novels that rival The Outsiders and Catcher in the Rye for its ability to capture teen angst, frustration, and confusion in contemporary society, more so, even, for being set in the 21st century. Craig Thompson’s main character in Blankets might as well be a contemporary counterpart to Salinger’s Holden Caulfield. Bryan Talbot’s The Tale of One Bad Rat , J.P. Stassen’s Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda , and Gene Yang’s American Born Chinese examine local and global socio-political and socio-cultural issues and their effects on young adults, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis is finally gaining some of the mainstream recognition it deserves because of the film adaptation. Brian K.Vaughn and Niko Henrichon’s Pride of Baghdad makes as clear a statement via its use of animal characters as anything Orwell wrote.

Young adult literature is rife with exceptional examples of texts that defy genre; many graphic novels are excellent young adult literature, too, of course; therefore, we should not be surprised that the graphic novel is part of the death of genre discussion. But its unique form is what defines it, not its themes. Much of the confusion in calling sequential art narratives a genre rather than a form, format, or medium may be contributed to the novelty the form holds for many or to a lack of background knowledge and/or a lack of respect for those figures within the sequential art communities, via production and/or scholarship, that have taken it seriously for generations and have already established a vocabulary that has yet to meet a larger audience. It seems clear to me that much of the use of genre to describe comics and graphic novels comes from either a lack of understanding or a lack of education, or, at worst, a reluctance to accept new forms and “new” voices into already established notions of the literary. So, though Smith says “By denouncing genre, we may perhaps begin to expand the horizons of our adolescents” (49), when it comes to the graphic novel, by denouncing genre, perhaps we’ll move beyond preferences and privileges that, to me, sometimes seem adolescent.

Part III: Illustrative Activity for Teachers

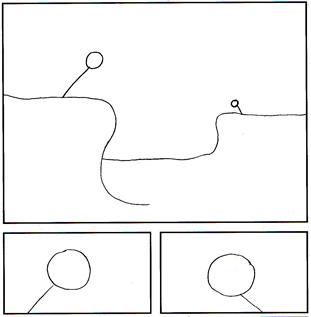

Figure 3. A three-paneled template of

Sequential Art Narrative

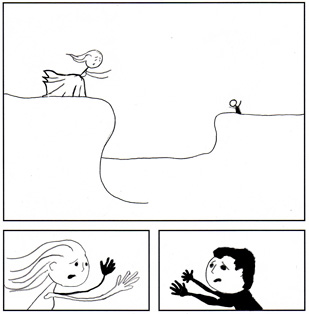

Though I encourage teachers to use the Grand Comic Book Database to look at images of comics and to consider the various genres the form makes available, I am herein including a more hands-on activity that I have shared with teachers and professors alike to illustrate that sequential art is a form that supports multiple genres. We start with one stark comic page (see Figure 3), with two figures separated by an indeterminable type of gulf. Two smaller panels beneath this scene show close-ups of our two characters. By changing the images just a little, we can turn this page into a genre, again and again.

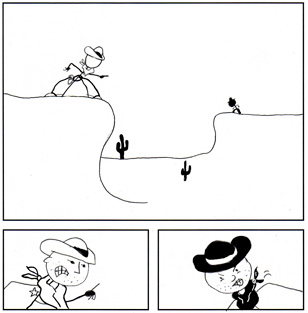

First, encourage a student to draw a white hat on the near figure, then a black hat on the far figure. Ask the student to draw holsters and guns on each figure and ask them to draw arms ready to grab the gun. They needn’t be elaborate as we began with stick figures initially (see Figure 4). Now ask the student to draw intense expressions on each face. Ask the students to identify the genre; if they still have trouble, add some cacti in the desert gulf or a horse or two. Soon you’ll see a western.

Figure 4. The template keeps its form but

supports the western genre.

If you need more illustration, add some dialogue:

Big Panel:

Sheriff: Dirt Dan! This gorge won’t keep me from bringing you to justice, cur! Dan: Ha! Like always yer tew steps behind, Sheriff!

Little Panel 1:

Sheriff: Draw on three. Your count, varmit!

Little Panel 2:

Dan: Wun…..tew……

Second, return to our stark comic page and ask another student to make one character a female in a flowing dress, the other a man in a ripped shirt (see Figure 5). Both the character’s arms should be outstretched as if they want to embrace the other. Make sure the female character’s hair is flowing and blowing in the wind. In the close-ups, have each character shedding a tear, and make sure to have the arms outstretched all the more.

Figure 5. The form stays the same, but now we have a romance.

If students can’t identify the comic as a romance, try this dialogue:

Big Panel:

Woman: Oh, Chet! I must see you; I don’t care what our parents say!

Chet: Oh, dear, how I long for you!

Little Panel 1:

Woman: My love!

Little Panel 2:

Man: My everything!

Figure 6. Again there is no formal change, but the format supports yet another genre, this time a Bible story.

You may repeat the process as many times as necessary. I favor a third page where Moses and Pharaoh are yelling at one another from across the Nile (see Figure 6). “You turn the very waters against me!?!” yells Pharaoh. “Not I, but my Lord!” Moses replies. I have found that this activity illustrates for adults and children alike that comics are not a genre but a form by which we may express stories in multiple genres. Feel free to use this activity in your classes, even, if you must, in a unit on genre studies.

James Bucky Carter recently earned his Ph.D. in English Education from the University of Virginia. He taught English and English Education courses at the University of Southern Mississippi before joining the English Department of The University of Texas at El Paso as an assistant professor in the fall of 2008. He has taught YA lit and graphic novels-related classes and has published several articles and book chapters on YA lit and sequential art narratives. His work has appeared in journals such as Marvels and Tales, ImageText, Contemporary Literary Criticism, and English Journal. In 2007, he wrote chapters for and acted as the general editor of Building Literacy Connections with Graphic Novels: Page by Page, Panel by Panel (NCTE). He also discusses intersections of literacy and sequential art at regional and national conferences.

Works Cited

Beckson, Karl, and Arthur Ganz. A Reader’s Guide to Literary Terms . New York: The Noonday Press, 1960.

Bucher, Katherine and M. Lee Manning. Young Adult Literature: Exploration, Evaluation, and Appreciation . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/ Merrill/Prentice Hall, 2006.

Carter, James Bucky. Textus/Praxis . Formerly accessible at at: http://nmc.itc.virginia.edu/E-folio/1/EDIS542/2004Fall1/cs/UserItems/jbc9f_555.html, 2004-2008.

———. “Carving a Niche” Graphic Novels in the English Language Art Classroom.” Building Literacy Connections with Graphic Novels: Page by Page, Panel by Panel . Urbana, IL: NCTE, 2007. 1-25.

———. “Comics, the Canon, and the Classroom.” Teaching Visual Literacy: Using Comic Books, Graphic novels, Anime, Cartoons and More to Develop Comprehension and Thinking Skills . Eds. Nancy Frey and Douglas Fisher. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2008. 47-60.

Chabon, Michael. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay . New York: Picador, 2001.

Cope, Bill and Mary Kalantzis, eds. Multiple Literacies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures . New York: Routeledge, 2000.

Dean, Deborah. Genre Theory: Teaching, Writing, and Being . Urbana, IL: NCTE, 2008.

Donelson, Kenneth L. and Alleen Pace Nilsen. Literature for Today’s Young Adults . 7th edition. Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon, 2005.

Eisner, Will. A Contract with God and other Tenement Stories. New York: DC Comics Library Edition, 1996.

———. Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative . Tamarac, FL: The Poorhouse Press, 1996.

———. Comics and Sequential Art . Tamarac, FL: The Poorhouse Press, 2002.

Frey, Nancy and Douglas Fisher. Eds. Teaching Visual Literacy: Using Comic Books, Graphic Novels, Anime, Cartoons and More to Develop Comprehension and Thinking Skills . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2008.

The Grand Comic Book Database. Accessed 2 April 2008 at http://www.comics.org .

Grossman, Austin. Soon I Will Be Invincible . New York: Pantheon, 2007.

Haddon, Mark. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime . New York: Vintage Contemporaries. 2003.

Hinton, S.E. The Outsiders . New York: Puffin Classics, 2003.

Lesesne, Teri S. “Of Times, Teens, and Books.” Adolescent Literacy: Turning Promise to Practice . Eds. Kylene Beers, Robert E. Probst, and Linda Rief. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2007. 61-80.

Lyga, Barry. The Astonishing Adventures of Fanboy and Goth Girl . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics . New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

McTaggart, Jacquelyn. “Using Comics and Graphic Novels to Encourage Reluctant Readers.” Reading Today 23.2 (2005): 46.

———. “Graphic Novels: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” Teaching Visual Literacy: Using Comic Books, Graphic Novels, Anime, Cartoons and More to Develop Comprehension and Thinking Skills . Eds. Nancy Frey and Douglas Fisher. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2008. 27-46.

Moore, Perry and TK. Hero . New York: Hyperion. 2007.

Myers, Walter Dean. Monster . New York: Harper Tempest, 1999.

———. Autobiography of My Dead Brother . New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

Myracle, Lauren. ttfn . New York: Amulet, 2006.

——— l8r g8r . New York: Amulet, 2007

Picoult, Jodi. The Tenth Circle . New York: Washington Square Press, 2006.

Salinger, J.D. The Catcher in the Rye . Little, Brown and Company. 1951.

Satrapi, Marjane. The Complete Persepolis . New York: Pantheon, 2007.

Selznick, Brian. The Invention of Hugo Cabret . New York: Scholastic, 2007.

Smagorinski, Peter. T eaching English by Design . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2008.

Smith, Scot. “The Death of Genre: Why the Best YA Fiction Defies Classification.” The ALAN Review 35.1 (2007): 43-50.

Spinelli, Jerry. Stargirl . New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

Stassen, J.P. Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda . New York: First Second, 2006.

Stoker, Bram. Dracula . New York: Pocket Books, 2003.

Talbot, Bryan. The Tale of One Bad Rat . Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse, 1995.

Thompson, Craig. Blankets . Marietta, GA: Top Shelf, 2003.

Vaughn, Brian K. and Adrian Alphona. Runaways Volume 1: Pride and Joy . New York: Marvel, 2003.

——— and Niko Henrichon. Pride of Baghdad . New York: Vertigo, 2006.

Versaci, Rocco. This Book Contains Graphic Language: Comics as Literature . New York: Continuum, 2007.

———. “‘Literary Literacy’ and the Role of the Comic Book: Or, ‘You Teach a Class on What?’” Teaching Visual Literacy: Using Comic Books, Graphic Novels, Anime, Cartoons and More to Develop Comprehension and Thinking Skills . Eds. Nancy Frey and Douglas Fisher. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2008. 91- 112.

Yang, Gene. American Born Chinese . New York: First Second, 2007.