WILLA v17 - Breaking into the Superhero Boy's Club: Teaching Graphic Novel Literary Heroines in Secondary English Language Arts

Breaking into the Superhero Boy's Club:

Teaching Graphic Novel Literary Heroines in Secondary English Language Arts

by Katie Monnin

I wish to show that elegance is inferior to virtue, that the first object of laudable ambition is to obtain a character as a human being, regardless of the distinction of sex.

I am often asked: "Graphic novels are longer comic books with superheroes, right?" My response: "Actually, graphic novels are more of a cousin to the comic book. And many are not about superheroes. Many focus on literary heroines."

This article is about teaching graphic novel literary heroines in secondary English Language Arts (ELA). But before we look at how to teach graphic novel literary heroines in ELA, let's take a look back at why it is so important for ELA teachers to, first and foremost, begin to use graphic novels in their classrooms.

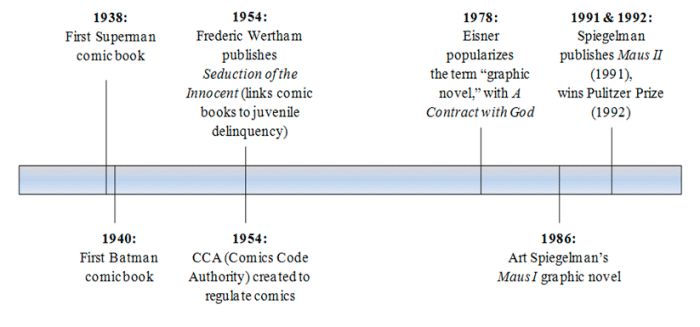

In 1978, following over thirty years of criticism, many comic artists had grown tired of hearing that comics were juvenile, lowbrow, and/or not "serious" literature; some critics had even gone as far as to claim that comic books were linked to a rise in juvenile delinquency ( Hajdu, 2008 ). In response to these critics, many comic artists felt the need to prove that comic book literacies (the combination of print-text literacies and image literacies to tell story) could indeed work on a literary level. One comic artist in particular stands out. In 1978, Will Eisner wrote a graphic novel called A Contract with God (1978), and he is often credited with popularizing the term.

While a comic book is typically associated with a famed superhero who follows a singular plotline, from Event A (need for superhero) to Event B (superhero saves the day), a graphic novel pursues deeper literary involvement, a more intense relationship with the conventions and styles found in canonical, print-text literature. A graphic novel, in short, adopts the elements of story traditionally taught in ELA classrooms, elements of story considered worthy of serious literary attention. The point: Even though the graphic novel is related to the comic book, it is vastly more independent in terms of format and literary intention.

Despite the intentions behind the graphic novel, however, many teachers still have questions. Since I work with pre-service and in-service teachers, I am often asked: Can the graphic novel really be used in ELA teaching and learning as a valid literary format? Absolutely! The graphic novel not only requires its own unique label as a valid literary format, but also can be used in ELA classrooms to broaden preconceived notions about comic books and their association with male superheroes.

For example, over the last ten to fifteen years the graphic novel literary heroine has received significant amounts of attention ( Gustines, 2006 ; Hajdu, 2008 ; Harris, 2008 ; Nagy, 2009 ; McCloud 2000 , 2006 ; O'Quinn 2008 ). But, you might wonder, why the sudden attention to the graphic novel literary heroine? The story of the graphic novel literary heroine actually begins with Art Spiegelman's Maus I (1986) and Maus II (1991), which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992. Because Maus I and Maus II were so [end page 20] popular and so well accepted as "literary," they are often cited as the first two graphic novels to finally break through the mainstream divide that still lingered between the comic world's perception of graphic novels and the general public's perception of graphic novels.

In other words, Maus I and Maus II broke through what was at first seen as "comic-like" and presented the graphic novel as a valid literary format to the general public. Those outside of the comic world who had previously felt that highbrow literature could only be found in print-text literacies actually found themselves labeling a graphic novel as highbrow literature. In short, since the publication of Eisner's A Contract with God (1978) and Spiegelman's Maus I (1986) and Maus II (1991), the graphic novel has been continuously experiencing a coming of age period. And although this coming of age has had many focal points, this article will focus on the specific coming of age experiences related to the graphic novel literary heroine ( Carter, 2007 ).

So, what is a "graphic novel literary heroine?" Due to the graphic novel's desire to operate on the same level as canonical, print-text literature, the graphic novel literary heroine is the main female character—just like it would be in print-text literature ( Carter, 2007 ; Frey & Fisher, 2008 ; Schwartz, 2007 ). But, opposed to print-text literature, the graphic novel presents its literary heroine in more than one manner. The graphic novel literary heroine is represented with both print-text literacies and image literacies. Both words and images define the graphic novel literary heroine.

One of the most recognizable graphic novel literary heroines to appear in many ELA settings is from Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis I (2004). Set during the Islamic Revolution in Tehran, Iran, Persepolis' main character, Marjane herself, presents one little girl's perspective on what it was like to grow up during this troubled time. And, just like Maus I and Maus II , Persepolis also captured the general public's interest in reading graphic novels as valid literary texts, receiving numerous literary awards (in 2004, it received the ALA Alex Award, YALSA Best Books for Young Adults, Booklist Editor's Choice for Young Adults, New York Public Library Books for the Teen Age, and School Library Journal Adult Books for Young Adults). Despite the graphic novel's growing popularity and the specific attention being paid by some scholars to the modern-day graphic novel literary heroine ( Carter, 2007 ), however, the graphic novel literary heroine's place in ELA teaching and learning is still in its early years of growth. Thus, this writing hopes to take the discussion about the graphic novel literary heroine, and her role in ELA teaching and learning, one step further.

In order to take this step, this article will present two ELA classroom studies where graphic novels and their literary heroines were emphasized. Snapshots of what occurred in these two high school ELA classrooms will be offered, and, it is hoped that ELA teachers will find that graphic novels with strong literary heroines:

- Can be aligned to the IRA/NCTE standards, and

- Can help move students away from the aged assumption that what appears comic-like and about superheroes might actually be a graphic novel with an unmasked cape-less literary heroine.

Teaching Graphic Novels with Strong Literary Heroines in Secondary ELA

Over the course of two school years, in two high school ELA classrooms, I aligned two graphic novels with strong literary heroines to the IRA/NCTE standards.

The two graphic novels of choice were: Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis I (2004) and Kazu Kibuishi's Daisy Kutter: The Last Train (2006). These two graphic novels were chosen for the following reasons:

- First, each graphic novel focuses on the development of a literary heroine.

- Second, each adopts the elements of story found in the IRA/NCTE standards.

And even though all of the IRA/NCTE standards can be applied to teaching graphic novels in secondary [end page 21]

| IRA/NCTE Standard 1 | Students read a wide range of print and non-print texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works. |

| IRA/NCTE Standard 11 | Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities. |

ELA (Carter, Monnin, Kelly, under review), Standard 1 and Standard 11 were deemed most appropriate and fitting for this work (see Figure 1). Because of its dual focus on building student understanding of a wide range of print literature, Standard 1 was deemed applicable to teaching reading with graphic novels. Standard 11 was also deemed appropriate, particularly because of its emphasis on asking students to be writers within a variety of literacy communities. In short, since the graphic novel format places value on both print-text literacies and image literacies, it is easily aligned to Standard 1, which focuses on students reading a diverse range of literature, and to Standard 11, which focuses on students writing with multiple literacies.

With these two IRA/NCTE standards in mind, let's next look at some snapshots of what occurred in these two ELA classrooms where graphic novels with strong literary heroines were treated as valid literary texts. These pedagogical snapshots are presented in a before reading, during reading, and after reading format.

Before Reading

Before reading the graphic novels, it was important to build student schema. Since most students still assumed that graphic novels were somewhat of an identical—but longer—twin to the comic book, they were first shown a brief, historical timeline focused on the development of the graphic novel (see Figure 2).

A Brief Graphic Novel Timeline

[end page 22]

| K | W | L |

|---|---|---|

| What do you Know about graphic novel literary heroines? | What do you Wonder about graphic novel literary heroines? | What do you want to Learn about graphic novel literary heroines? |

To build upon their new schema about the history of the graphic novel, and in reference to Standard 1, students were then given a KWL chart (Ogle, 1986) that focused specifically on the role of the graphic novel literary heroine. (See Figure 3.)

During Reading

Once students filled out the K and the W columns of the KWL chart, they were next asked to read specific sections of the graphic novel. After each section, students were asked to add what they learned about the graphic novel literary heroine to the L column.

Again focusing on Standard 1, and during reading, students were then asked to fill out a cartoon characterization reading strategy. On their cartoon stick-figure, students were to add features, personality traits, and/or characteristics that they felt best represented the graphic novel literary heroine (See Figure 4).

Cartoon Stick Figure

Directions: While you are reading the graphic novel, pay close attention to the literary heroine and add some features, personality traits, and /or characteristics o the below stick figure. Make sure that your decisions are based upon details found in the graphic novel.

After Reading

After reading, and in reference to IRA/NCTE Standard 11, students were next assigned a writing activity that built upon their visual and written descriptions of the graphic novel literary heroine seen in Figure 4. The directions read as follows:

Please review, both visually and in writing, the decisions you made to represent the graphic novel literary heroine. Make a list of the 3 MOST important aspects of this literary heroine. After completing your list, decide upon two reasons to support each of your three choices.

After writing these lists and their supporting reasons, the last direction read: "Finally, reflect on your list, and your supporting reasons, and write an expository essay about your graphic novel literary heroine."

Findings from Teaching Graphic Novel Literary Heroines in Secondary ELA

After the graphic novels were read and the student work collected, I quickly realized that this was some of the most thoughtful work of the year. After reading and then writing about a graphic novel, students expressed a more thorough, contemporary understanding of the word "literacy." Two specific themes emerged from the students' work, indicating that they were now defining "literacy" as including both print-text literacies and image literacies:

- In terms of their reading responses (Standard 1), students indicated that they now considered both print literacies and image literacies as valid literary literacies.

- In terms of writing (Standard 11), students indicated that they now desired to write [end page 23] with both print literacies and image literacies as well.

Let's begin by discussing how students' reading responses (Standard 1) indicated a more thorough understanding of the word "literacy." When viewing the "K" and "W" columns of their KWL charts, students only used words to describe what they knew and wondered about the graphic novel literary heroine. After they read the graphic novel, however, and were asked to fill out the "L" column of the KWL chart, students not only used words, but also images. Eighty-nine percent of the students KWL charts displayed a transition from using only print-text literacies in the K and W columns, to using both print-text literacies and image literacies in the L column.

Along with indicating that their reading experience had undergone a transition from valuing print-text literacies alone to valuing print-text literacies and image literacies together, students also indicated that they now viewed the act of writing as involving both print-text literacies and image literacies. Students exhibited this transition in regards to writing in two steps: first, they asked if they would be "allowed" to write paragraphs that included both print-text literacies and image literacies; and, second, students used both print-text literacies and image literacies to write about the graphic novel literary heroine. Breaking down many of the visual stereotypes typically missing in conversations about print-text only literature, students used both words and images to highlight what they learned about the graphic novel literary heroine. For example, one student wrote, "Daisy Kutter is like a" and drew a female stick figure wearing a cowboy hat. This student then wrote, "I never thought of girls as cowboys." Describing Marjane's autobiographical character, another student drew a map of the country Iran and wrote "1979" underneath the country's borders. Then, this same student added a little girl standing near a city labeled "Tehran." This second student then wrote, "If she did not write this book, I would not have known how a little girl experienced Middle East problems. I used to think of men fighting wars," which was followed by an illustration of two armies of men facing each other with guns. Taking their cue from the graphic novel format, students demonstrated that they not only understood that they could read with both print-text literacies and image literacies, but also write with both print-text literacies and image literacies.

Implications for ELA Classroom Practice

One implication suggested by this work is that graphic novels can be aligned to the IRA/NCTE standards. Students were able, in short, to work through the activities presented in a before reading, during reading and after reading format, and, in doing so, successfully demonstrate their abilities to read and write about graphic novels.

Another implication suggested by this work is that, when asked to read a graphic novel, students are likely to define literacy as including both print-text literacies and image literacies. As many literacy scholars ( Buckingham, 2003 ; Carter, 2007 ; Hobbs, 2007 ; Kress, 2003 ; The New London Group, 1996 ) now advocate, our lives are no longer dominated by print-text literacies alone, but, instead, by a variety of literacies. The world told and the world shown are different worlds ( Kress, 2003 ). During our current time in history, then, it becomes imperative that students be able to read and write with both print-text literacies and image literacies, for both types of literacy singularly and together influence the modern reading world ( Buckingham, 2003 ; Kress, 2003 ; The New London Group, 1996 ).

A final implication of this work is subtle, yet significant. Because students were able to define/describe the literary heroine in both words and images, it is worthwhile to note that it might be wise for the ELA community to conduct further research on the issue of gender representation in graphic novels. For instance, one question that this work begs us to ask in the future is: "In what ways are students able to use both print-text literacies and image literacies to define/describe the graphic novel literary heroine?" Or, perhaps, "In what ways do students use print-text literacies and image literacies [end page 24] to represent male and female graphic novel characters?"

Final Thoughts

Since we are living during a time that many literacy scholars see as the greatest communication revolution of all time, there are many, many more questions that can be asked about the graphic novel's place in ELA teaching and learning. This work merely presents a few ideas for not only aligning graphic novels to the IRA/NCTE standards, but also for teaching graphic novels with strong literary heroines. As we pay more attention to the graphic novel, and its place within ELA teaching and learning, I hope that more teachers will find and share all of the interesting and diverse ways they too have fit graphic novels into their ELA curriculums. In fact, I encourage teachers to share their ideas on my blog: http://teachinggraphicnovels.blogspot.com/

As I end my thoughts on teaching graphic novels with strong literary heroines in these two secondary ELA classrooms, I keep thinking about a quotation one of my students wrote out and gave to me following our work with graphic novels:

A friend is someone who gives you a book you have not read.

—A. Lincoln

References

Buckingham, D. (2003). Media education: Literacy, learning and contemporary culture . Malden, MA: Polity.

Carter, J. B. (2007). Building literacy connections with graphic novels: Page by page, panel by panel . Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Carter, J. B., Monnin, K., & Kelley, B. (2009). Letting the (krazy) kat out of the bag: Graphic novels and the English language arts standards . Manuscript submitted for publication.

Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2008). Teaching visual literacy . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Gustines, G. G. (2006, November 25). For graphic novels, a new frontier: Girls. The New York Times .

Hajdu, D. (2008). The ten-cent plague:The great comic-book scare and how it changed America . New York: FSG.

Harris, V. J. (2008). Selecting books that children will want to read. The Reading Teacher , 61(5), 426-430.

Hobbs, R. (2007). Reading the media: Media literacy in high school English . New York: Teachers College Press.

Kibuishi, K. (2006). Daisy Kutter: The last train . Irving, TX: Viper.

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the new media age . New York: Routledge.

McCloud, S. (2006). Making comics: Storytelling secrets of comics, manga and graphic novels . New York: HarperCollins.

McCloud, S. (2000). Reinventing comics: How imagination and technology are revolutionizing an art form . New York: HarperCollins.

Nagy, E. (2009, January 27). What a girl wants is often a comic. Publisher's Weekly .

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multi-literacies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review , 66(1), 60-92.

Ogle, D. (1986). KWL: A teaching model that develops active reading of expository text. The Reading Teacher , 32, 564-570.

O'Quinn, E. J. (2008). "Where the girls are." ALAN Review , 35(3), 8-14.

Satrapi, M. (2003). Persepolis: The story of a childhood . New York: Pantheon.

Schwartz, G. (2007). Media literacy, graphic novels and social issues. Studies in Media & Information Literacy Education , 7(4), 1-11.

Wertham, F. (1954). Seduction of the innocent . New York: Rinehart. [end page 25]