ALAN v35n2 - How Todd Strasser Became Morton Rhue

How Todd Strasser Became Morton Rhue

Four years ago I was at the International Youth Library in Munich researching the status of the young adult novel outside the United States. Since this segment of the American publishing industry was experiencing a fair amount of experimentation in form, I was interested in discovering the extent to which that might be happening elsewhere. As part of that research, I interviewed Robert Elstner, a public youth librarian in Leipzig. One of the questions I asked was along these lines: “Can you pinpoint anything that marked the rise of the young adult novel in Germany? A particular book, maybe?”

The answer I got was Die Welle by Morton Rhue. That book title continued to come up in conversations during the subsequent five months I spent in Germany, always as a significant turning point in German youth literature. The author’s name didn’t ring a bell, but neither did many of the other names I was encountering. Then someone mentioned that the author was American. Here was an American book that had exerted such influence on German young adult literature, and I had heard of neither the book nor its author. When I returned home, I discovered that Die Welle was a translation of an American book called The Wave by someone whose work I thought I knew well: Todd Strasser. I set out to find the story behind this quirky little piece of publishing trivia: how and why did Todd Strasser become Morton Rhue?

Morton Rhue is practically a household name in Germany. To understand why, it is necessary to return to the origins of The Wave, which began long before Morton Rhue was a gleam in his alter ego’s eye. It all started with an essay by Ron Jones, who was a classroom teacher in Palo Alto, California. At some point in the 1970s, he wrote an essay describing an experiment he conducted in his social studies class in 1967, his first year of teaching. 1 According to Jones, he and his class had been studying the Third Reich, and as always, students were questioning how the German people could have gone along with Hitler. Jones had no answer, of course, and decided the next day to introduce an exercise in class that might help lead to an answer. This is how he described it in his essay:

On Monday, I introduced my sophomore history students to one of the experiences that characterized Nazi Germany. Discipline. I lectured about the beauty of discipline. How an athlete feels having worked hard and regularly to be successful at a sport. How a ballet dancer or painter works hard to perfect a movement. The dedicated patience of a scientist in pursuit of an Idea. it’s discipline [sic]. That self training. Control. The power of the will. The exchange of physical hardships for superior mental and physical facilities. The ultimate triumph

To experience the power of discipline, I invited, no I commanded the class to exercise and use a new seating posture; I described how proper sitting posture assists mandatory concentration and strengthens the will. In fact I instructed the class in a sitting posture. This posture started with feet flat on the floor, hands placed flat across the small of the back to force a straight alignment of the spine. “There can’t you breath more easily? You’re more alert. Don’t you feel better.”

We practiced this new attention position over and over. I walked up and down the aisles of seated students pointing out small flaws, making improvements. Proper seating became the most important aspect of learning. I would dismiss the class allowing them to leave their desks and then call them abruptly back to an attention sitting position. In speed drills the class learned to move from standing position to attention sitting in fifteen seconds. In focus drills I concentrated attention on the feet being parallel and flat, ankles locked, knees bent at ninety-degree angles, hands flat and crossed against the back, spine straight, chin down, head forward. . . .

It was strange how quickly the students took to this uniform code of behavior. I began to wonder just how far they could be pushed. Was this display of obedience a momentary game we were all playing, or was it something else. Was the desire for discipline and uniformity a natural need? (Jones)

Building on their acceptance of this regimentation, he instituted several rules, such as requiring students to stand when called upon and preface their response with “Mr. Jones.” Punctuality and readiness were emphasized.

The intensity of the response became more important than the content. To accentuate this, I requested answers to be given in three words or less. Students were rewarded for making an effort at answering or asking questions. They were also acknowledged for doing this in a crisp and attentive manner. Soon everyone in the class began popping up with answers and questions. The involvement level in the class moved from the few who always dominated discussions to the entire class. Even stranger was the gradual improvement in the quality of answers. Everyone seemed to be listening more intently. New people were speaking. Answers started to stretch out as students usually hesitant to speak found support for their effort. (Jones)

The following day, Jones walked into the classroom and saw the students in their seats, postures erect. Having gone into this without a game plan, he decided to continue it, and wrote on the board, “Strength through community.” The previous day had been about a discipline; now it was about community. Again, from his essay:

I made up stories from my experiences as an athlete, coach and historian. It was easy. Community is that bond between individuals who work and struggle together. It’s raising a barn with your neighbors, it’s feeling that you are a part of something beyond yourself, a movement, a team, La Raza, a cause. (Jones)

At the end of the class period, he made up a salute for class members, with fingers curled like a wave. He called it the third wave, taken from the surfer’s idea that the third wave is the largest. Although he claims he was not deliberately alluding to the Third Reich, the coincidence strains belief. As his students saluted each other in the halls, the cafeteria, or the gym, others wanted to be part of the Third Wave and on Wednesday thirteen students had skipped their own classes to attend Jones’s class. Wednesday’s focus was “Strength through Action,” and among the actions encouraged were to bring more students into the movement and to report any students who were not adhering to the rules. In all, nearly 200 were involved by the time Jones found a way to end the experiment, which he did by setting the students up to believe they were part of a nationwide movement and then exposing them to the truth: they had been manipulated.

The above account comes directly from Jones’s article. Whether it is entirely factual or has been shaped and embellished for effect is an important consideration but not one that is relevant here. What is important is that Jones’s article was picked by T.A.T. Communications, an independent production company, as the basis for an ABC Afternoon Special, a series that ran from 1972 to 1988 and usually consisted of scripts written from young adult problem novels. As someone who watched this series commented, “most of the specials dealt with the same subjects every two years. . . . teen pregnancy, drug addiction, divorcing parents, or some other societal problem that affects kids and teens” (ABC). One of the actors who co-starred in the film version of The Wave said, “We knew when we made The Wave that it was way out there as far as this programming format was concerned” (ABC). In fact, the finished program packed such a punch that the network delayed showing it as an ABC Afternoon Special and instead ran it during prime-time on its ABC Theater for Young Americans on October 4, 1981. It garnered both an Emmy and a Peabody Award for that year and was rebroadcast as an ABC Afternoon Special in 1983.

Enter Todd Strasser, who was hired to write a novel of the story based on the filmscript. Strasser was working as a journalist with one teen novel to his credit, Angel Dust Blues. Published in hardcover in 1979, Angel Dust Blues was scheduled to come out in paperback from Dell Publishing in 1981. Meanwhile, Dell had made an agreement with the film production company to publish the novelization of The Wave as a paperback original and assigned the writing job to Strasser. It was work for hire, with the copyright belonging to Dell and T.A.T. Communications. The first Dell printing came out in October 1981, presumably to coincide with the airing of the television show.

Rights to The Wave were bought by the German publisher Ravensburger and the German edition was published in paperback in 1985 with translation by Hans-Georg Noack, who also translated The Outsiders into German. The book exists in several editions in Germany—trade paperback, and school editions in English and German that include supplementary material, including a biography of the author, historical background, text analysis and interpretation, assignments, themes, reviews, and other material for use in a classroom setting.

It is safe to say that almost everyone raised in German schools from the late 1980s on has heard of this book. I asked a 17-year-old German girl who was visiting me if she had read Die Welle and she said yes, as did a much older acquaintance, who added, “by Morton Rhue.”

Todd Strasser’s webpage contains a button “Für Deutsche Leser,” which addresses the German reader and explains the connection between Todd Strasser and Morton Rhue. When giving background about The Wave, he writes, “To me, one of the most rewarding aspects of The Wave is knowing that it is required reading not only in your class, but in most of Germany as well.” In addition to discussing The Wave, Strasser’s site for German readers describes the two other books of his that have been translated into German. Can’t Get There from Here, about street kids living in New York, was published in Germany as Asphalt Tribe, and Give a Boy a Gun, about a school shooting spree, was published under a German title roughly translated as “I pick you off.” Both list the author as Morton Rhue.

The name Todd Strasser means nothing in Germany—the name Morton Rhue carries a lot of weight and has marketing cachet. Morton Rhue has a very different image than Todd Strasser. Rhue’s books are raw and gritty. He writes about street kids in New York, about adolescent misfits who go on a shooting rampage in their school, and about teens like Robert who are losers until something like The Third Wave comes along to give them a sense of worth. Asphalt Tribe was one of five books nominated by the Youth Jury for the prestigious German Youth Literature Prize.

Todd Strasser, on the other hand, has written over 80 books, including novelizations and light-hearted series books for younger teens. Help, I’m Trapped in My Teacher’s Body has launched 16 other Help, I’m Trapped books. His series have names like Impact Zone, Don’t Get Caught, Camp Run-Amok, and Against the Odds. His serious books are well received, but he is perhaps best known in North America for his more popular books.

To return to the question I began with, How did Todd Strasser become Morton Rhue? In 1981, Strasser’s second novel, Friends till the End, was due out from Delacorte Press, Dell’s hardcover imprint, and his first novel, Angel Dust Blues, was being released by Dell in paperback on the same list as The Wave. The publisher decided that it was better not to have two books by the same author coming out in the same season, and so Strasser was asked to come up with a pseudonym for The Wave. That explains why. Finally, here is how, taken from the page of his website directed at German readers:

Perhaps he was influenced by his sojourn in Europe as a young man: Strasser sounds similar to the German word “Strasse” [which means street]. In French “Strasse” is “rue.” To capture the r sound, the h was added to yield “Rhue.” “Todd” sounds very much like the German word “Tot” [which means dead]. “Tot” equals “mort” in French. And since “Mort Rhue” sounds choppy, Todd Strasser became Morton Rhue. (Todd Strasser.com. May 15, 2006. www.toddstrasser.com/html/fur.html)

In America, Morton Rhue had a very short life. Not long after the first printing, Dell dropped the pseudonym from the cover of The Wave, replacing it with Strasser’s name, which had started to gain recognition among young adult readers. The Wave is still in print under the Dell Laurel-leaf imprint and occasionally gets a facelift in the form of new cover art; the most recent edition was issued in March 2005. Judging from reader comments in online forums, the book is read both for school assignments and as recreational reading, and it continues to make the same strong impression it first made over twenty-five years ago.

American cover, published

by Simon & Schuster, 2007

German cover, published

by Ravensburger, 2007

German cover Die Welle,

1985

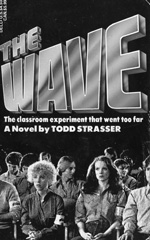

Original cover The Wave,

1981

Current cover T he Wave,

2005

In Germany and in the United Kingdom, however, Morton Rhue is alive and well. In the U.K., he is known only as the author of The Wave, which has remained in print with periodically updated covers, the most recent being in 2007. In Germany, however, not only does Morton Rhue live on in the minds of two decades of German readers as author of Die Welle, but his list of books grows longer by the year. His latest book in translation there is Boot Camp, not coincidentally the name of Todd Strasser’s latest book in the U.S. With each book, Morton Rhue gains new readers, yet Die Welle is the one book that spans the generations. Of all the German readers who know that book, few, if any, realize its provenance. For older readers especially, the story will always belong to the noted American writer Morton Rhue.

End Note

1. The original publication of Jones’s essay, “The Third Wave,” is somewhat in dispute. One source (Strasser) cites it as having “appeared in a Whole Earth Catalogue sometime in the early 1970s.” The essay reproduced on two websites (Jones) carries the date 1972. Finally, a search of the database AltPressIndexArchive, which spans the years from 1960 to 1990, shows the article as having been published in the North Country Anvil in 1974. It is possible that the essay appeared in more than one publication in the 1970s.

Susan Stan is a professor at Central Michigan University, where she teaches courses in literature for children and young adults, often with international focus. She has been involved with the USBBY-CBC Outstanding International Books award list, launched in 2006 and served on the 2007 Outstanding International Books committee.

Works Cited

“ABC Afternoon Special.” Jump the Shark. May 16, 2006. <www.jumptheshark.com/a/abcafterschoolspecial.htm>.

“Für Deutsche Leser.” Todd Strasser.com. May 15, 2006. <www.toddstrasser.com/html/fur.html>.

Hinton, S.E. The Outsiders. New York: Delacorte, 1967.

Jones, Ron. “The Third Wave.” May 16, 2006. <www.vaniercollege.qc.ca/Auxiliary/Psychology/Frank/Thirdwave.html>.

Jones, Ron. “The Third Wave.” North Country Anvil 28 (Fall 1978): 23.

Rhue, Morton. Asphalt Tribe. Tr. By Werner Schmitz. Ravensburg: Ravensburger, 2005.

Rhue, Morton. Boot Camp. Tr. By Werner Schmitz. Ravensburg: Ravensburger, 2007.

Rhue, Morton. Die Welle. Tr. by Hans-Georg Noack. Ravensburg: Ravensburger, 1985.

Rhue, Morton. Ich knall euch ab! Tr. By Werner Schmitz. Ravensburg: Ravensburger, 2002.

Strasser, Todd. Angel Dust Blues. New York: Delacorte, 1979.

Strasser, Todd. Boot Camp. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Strasser, Todd. Can’t Get There from Here. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004.

Strasser, Todd. Friends till the End. New York: Delacorte, 1981.

Strasser, Todd. Give a Boy a Gun. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000.

Strasser, Todd. Help, I’m Trapped in My Teacher’s Body. New York: Scholastic, 1993.

Weinfield, Leslie “Remembering the 3rd Wave.” Ron Jones Website. http://www.ronjoneswriter.com/wave.html. May 16, 2006.