JVER v25n1 - The Critical Incident Technique in Job Behavior Research

The Critical-Incident Technique In Job Behavior Research

Wanda L. Stitt-Gohdes

University of Georgia

Judith J. Lambrecht

University of MinnesotaDonna H. Redmann

Louisiana State University

AbstractThe critical incident technique is examined as representing a qualitative approach to understanding requirements of the work world. The technique itself is described, followed by an explanation of how themes are identified and coded using sample interviews. Data analysis techniques are illustrated using sample data sets from a recent investigation of office work requirements. Finally, an approach for drawing conclusions from critical incident data is discussed.Approaches to Job AnalysisAs workplaces and educational settings become more complex, educational researchers are wise to consider employing a variety of research methodologies and data collection techniques that will properly capture the types of information and data needed to address the educational problems of today and tomorrow. We focus on one of several qualitative methodological tools available to researchers, the critical incident technique (CIT). The CIT is a tool used in qualitative research that can capture the complexity of job behavior in terms of the job's social context. Key concepts and techniques for conducting critical incident interviews are discussed. Issues related to the data coding process and analysis process are subsequently addressed. Finally, the process of drawing inferences from data via the critical incident technique will be examined.

The CIT, a qualitative approach, employs the interview method to obtain "an in-depth analytical description of an intact cultural scene" ( Borg & Gall, 1989, p. 387 ). According to Gay and Diehl ( 1992 ), behavior occurs in a context, and an accurate understanding of the behavior requires understanding the context in which it occurs. The culture of an organization can have a direct influence on the behavior of employees. Qualitative approaches are appropriate methods for understanding real-world job settings. The critical incident approach, in particular, is an appropriate tool that can be used to analyze jobs in the social context in which they occur. Not only is it important to understand the appropriateness of the CIT as a qualitative research tool, it is also important to understand that the approach is appropriate for job analysis.

Critical Incident Technique ApproachCurrently, there are fundamentally different approaches that can be used to analyze job requirements in a specific work context so educational programs can be developed to prepare future employees. Three of these will be briefly described: the skills component model, the professional model, and the general components model.

The skills component model is a task-analytic approach to describe job duties, tasks, skills, and generally broad competencies ( Bailey & Merritt, 1995 ). Work settings reflective of the skills components model have been characterized as Tayloristic in their orientation to work and supervision. Planning and control reside with management, and precise instructions are provided to workers who carry out pre-determined and perhaps repetitive procedures under close supervision. Time-and-motion studies may provide the basis for decisions about the most efficient work practices. Tools that are used for carrying out Skills Components Job Analysis are DACUM (Develop A Curriculum), Functional Job Analysis (FJA), and V-TECS (Vocational-Technical Consortium of States). The most significant disadvantage in using these models in job analysis according to Bailey and Merritt ( 1995 ) is work fragmentation. Work fragmentation is the result of dissecting work-based activities into component parts. This, in turn, can lead to instructional materials that are highly task-specific. This process of dissecting jobs into specific component parts usually reduces worker roles and learning needs to a series of unrelated job functions or skills.

The second is the professional model, a professionally oriented, more holistic approach that seeks to understand job requirements in specific work settings or social contexts. It also has the goal of identifying job competencies for employment preparation, but it is less likely than the task-analytic approach to assume that general skills and competencies can be taught separately from specific work contexts ( Bailey & Merritt, 1995 ). This model captures the complexity of jobs in high-performance organizations where workers have more discretion in their jobs and more responsibility for planning and problem solving. The focus of professional job analysis is on jobs in a broader sense and the incorporation of the social context of jobs.

The third approach, the general components model, differs from the first two in that it extends beyond the requirements of a single job category or occupational group. Descriptions of broad job requirements are used for developing curriculum appropriate for all students and for many different jobs. This approach focuses on the generic skills or traits that are needed by individuals and not necessarily on the tasks found in a particular organization.

Vocational and technical education has depended largely on the skills component model to describe job competencies and derive educational program requirements. However, because of the dynamic nature and increased use of computing technology in business and industry, job competencies are being viewed more broadly. The broadest approach to describing employment requirements is to separate them from specific jobs or occupational areas and describe general competencies. The professional model can serve as an alternative, more holistic work analysis procedure that is tied to particular employment settings and resulting work cultures. As a tool of professional model analysis, the CIT can function as an important means for gathering information about events that are rich in work requirements. Also, the CIT approach potentially compliments task analysis information in an attempt to extend information to broad job categories in similar settings.

Preparing to Use the Critical Incident Technique ProcessThe critical incident technique has recently been identified among the job-analysis tools most likely to capture a holistic and professionally-oriented description of work-place requirements ( Bailey & Merritt, 1995 ; Merritt, 1996 ). The technique can capture employees' interpretations of their work settings. CIT is "an epistemological process in which qualitative, descriptive data are provided about real-life accounts" ( Di Salvo, Nikkel, & Monroe, 1989, pp. 554-555 ).

The CIT was developed by Flanagan ( 1954 ). His now famous article, The Critical Incident Technique, is considered by the Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology to be the most frequently cited article in the field of industrial/organizational psychology ( American Institutes for Research, 1998 ). The CIT is an outgrowth of studies done in the Aviation Psychology Program of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. Flanagan was faced with the problems of improving military flight training, bombing missions effectiveness, and combat leadership. On a large scale, he systematically asked trainees and veterans to describe exactly what they had done successfully and unsuccessfully with respect to a designated activity. Later, Flanagan formalized this data collection process and defined it as a method of identifying critical job requirements. The process involves collecting factual stories or episodes about job behaviors that are crucial in performing a job effectively ( Zemke & Kramlinger, 1982 ). The American Institutes for Research ( 1998 ) defines CIT as a "set of procedures for systematically identifying behaviors that contribute to the success or failure of individuals or organizations in specific situations." The CIT is not an appropriate job analysis tool for every job. Rather, it is appropriate for jobs that have a flexible or undefinable number of correct ways to behave.

The structure of CIT involves (a) developing plans and specifications for collecting factual incidents (e.g., Determine from whom the information is to be collected. Determine methods of collection. Develop instructions about the data collection.), (b) collecting episodes/critical incidents from knowledgeable individuals, (c) identifying themes in the critical incidents, (d) sorting the incidents into proposed content categories, and (e) interpreting and reporting results. Data can be collected from observations or from viable self-reports, i.e., interviews. Classification and analysis of critical incidents are the most difficult steps because the interpretations are more subjective than objective ( Di Salvo et al., 1989 ).

The CIT has been used recently in a long-term project of the National Center for Research in Vocational Education (NCRVE) to understand leadership development in vocational education ( Finch, Gregson, & Faulkner, 1991 ; Lambrecht, Hopkins, Moss, & Finch, 1997 ). The approach of asking jobholders to provide in-depth descriptions of specific events in order to gain an understanding of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors has also been called the behavioral event interview. This particular label has been used to describe the research technique used to examine the higher-order critical thinking skills used in banking ( Bacchus & Schmidt, 1995 ) and to examine teachers' roles in the integration of vocational and academic education ( Schmidt, Finch, & Faulkner, 1992 ). Schmidt, Finch, and Moore ( 1997 ) used the CIT to examine professional development programs. The approach allowed them:

to stimulate interviewees' descriptions of professional development activities that helped teachers to meet students' school-to-work needs. Interviewees were also asked to describe the best school-to-work practices teachers had used, including those where they interfaced effectively with employers. The critical-incident technique was again used to help interviewees focus on describing examples of teachers' best practices.Another project completed for the NCRVE used the CIT to identify instructional practices in exemplary office technology programs ( Lambrecht, 1999 ).

For a national study sponsored by Delta Pi Epsilon (DPE), the critical incident approach was selected to determine factors that influenced primary computer users' successful assimilation into the workforce ( Lambrecht, Redmann, & Stitt-Gohdes, 1998 ). The CIT allowed the researchers to capture employees' interpretations of their work settings and was a method that could be used consistently by a national group of data collectors. The DPE national study will provide the context for illustrating how the CIT can be implemented.

Using the Critical Incident Interview TechniqueThe first step in the CIT process involves developing detailed plans and specifications for collecting factual incidents. The following types of decisions need to be made:

Purpose of Investigation

- What is the purpose of the investigation?

- From whom should information/data be collected?

- What is the most appropriate method to use? Observations? Interviews?

- What questions should be asked?

- Who should collect the data?

- Should the data collectors receive training on how to conduct the interviews?

- What instruction(s) need(s) to be developed for collecting the data?

- Should details about collecting data be provided to data collectors in written form?

As in any investigation, pertinent research questions must be identified. For the DPE national project, we wanted to gain a greater understanding of how employee socialization and organizational adaptability influence workplace learning within office settings. For other recent projects which have used the CIT, the primary purposes have included documenting examples of effective leadership from subordinates of recognized leaders ( Finch et al., 1991 ), obtaining examples of developmental experiences from exemplary leaders ( Lambrecht et al., 1997 ), identifying professional development practices of practicing teachers ( Schmidt et al., 1992 ), and to record effective teaching practices from teachers and students ( Lambrecht, 1999 ).

Determining ParticipantsA formal definition of research participants should be developed that will maximize useful information relevant to the purpose of the investigation. For the DPE national project, participants determined to be primary computer users were selected. We defined primary computer users as employees in an information processing area of a business using a desktop computer for completing more than 50% of job responsibilities.

Determining Methods for Collecting DataThere are basically two data collecting methods that can be used with a critical incident approach--observations or in-depth interviews. Observations are useful when examining unambiguous overt behavior, but are not appropriate for covert behavior, like decision-making. If observations (either in person or videotaped for later observation) are used, the role of the observer has to be predetermined. This role can range from complete participation within a group to removed observer where the individuals may not realize they are being observed ( Fraenkel & Wallen, 1996 ).

If the interview approach is employed, either face-to-face or telephone interviews can be conducted. The advantages of using in-person interviews include allowing the interviewer to read or react to nonverbal communication and to probe for in-depth responses. It is highly recommended that all interviews, even those conducted in person, be taped. By audio taping interviews, interviewer reliability can be monitored by examining the questions used by the interviewers. In the DPE national project, we chose face-to-face interviews to collect critical incidents about how primary computer users learned their job.

If telephone interviews are used, the process can be facilitated by allowing the interviewees to prepare in advance ( Lambrecht et al., 1997 ). Interviewees must also be informed and consent to having the telephone interview taped. Electronic devices are available which make it easy to record phone conversations onto cassette tapes.

After deciding the means for collecting data, the next decision involves determining who will collect the data. Several options exist including the researchers or a team of trained interviewers. This decision is based on the scope of the project. For a large-scale national project, such as the DPE study, a team of trained interviewers is probably most appropriate. In order to engage as many DPE chapters in the DPE national study as possible, we elected to use a national team of interviewers who were recruited from two national conferences. The project staff required interviewers to tape the 30- to 60-minute interviews. Completed tapes were sent to one of us, who in turn had the tapes transcribed. Transcribed interviews were returned to the interviewers who shared them with interviewees in order to allow the transcripts to be checked for accuracy and completeness. Cross-checking interviews helps ensure that inadvertent speaking errors are caught. Interviewees also get confirmation of genuine concern for capturing an accurate representation of their views.

Determining QuestionsQuestions used in the CIT should be ask people who are familiar with the situation being analyzed to provide examples of incidents that are critical to successful and unsuccessful performance. Incidents are usually anecdotal accounts of events that have actually occurred. Interviewees are asked to describe incidents in terms of (a) the circumstances preceding the event, (b) what exactly was done and why was it effective or ineffective, (c) the outcome or result of the behavior, and (d) whether the consequences of the behavior were under the employee's control ( Siegel & Lane, 1987 ). Critical incidents can be revealed in a number of ways as illustrated by these examples of probes. "Describe what led to the situation." "Exactly what was done that was especially effective or ineffective?" "What was the outcome or result of this action?" "Why was this action effective?" ( American Institutes for Research, 1998 ). We employed the following questions to guide face-to-face interviews:

Instruction for CIT Data Collectors

- Describe a critical/significant/important experience that is an example of what you do well in your current job.

• Why do you feel competent?

• How did you learn to do this?- Describe a critical/significant/important experience that is an example of a problem in your current position that you could not solve quickly on your own.

• What do you do when you have a problem?

• What resources do you use when you have a problem?

• When do you or have you felt incompetent and why?- What experiences would you like to have that would have helped you or could help you to become more competent?

- What other roles do you desire or would you like to pursue within the organization?

Consistency in the data collection process is key to the success of the CIT. A detailed set of procedures should be developed for preparing data collectors. These procedures should include:

- the purpose of the research,

- concise definition of individuals to be interviewed or observed,

- the interview process,

- steps for gathering data,

- interview techniques/tips,

- respondent demographic information sheet,

- interview questions, and

- sample letters to interviewee/respondents from interviewers.

If the research study is small scale and researchers are primarily responsible for conducting data collection, training for data collectors may not be necessary. However, if several data collectors will be employed, we recommend that some form of training be provided. Training can range from simply covering the basic steps of the interview process to critiques of role-playing activities. To ensure consistency, steps in the data collection process should be provided in written form.

Interview Techniques/TipsThe interview is a powerful tool for gathering information because it is flexible, can facilitate the active support of the interviewee, and can provide a multi-dimensional picture, e.g., nonverbal communication can be assessed ( Rossett & Arwady, 1987 ). While the interview is an excellent means for learning about problems or situations, it is a tool that may challenge the interviewer. Interviewers cannot control interviewees nor do they want to for fear of misdirecting the flow of information. It is also difficult for interviewers to change their interpersonal style to match the inclinations of respondents, e.g., a respondent may use a random spontaneous approach or a holistic approach ( Rossett & Arwady ).

The success of an interview can be enhanced by pre-interview preparation. For example, if an interviewer has an agenda and knows the purpose of the research, the interview process should go much smoother. Also, the interviewers should be prepared to address typical questions from interviewees concerning reasons for being selected, ways that results will be used, or issues of confidentiality.

To prepare the volunteer interviewers for the DPE national project, an instructional booklet was developed. The purpose of the research project was described along with an overview of the interview process and the criteria to use in identifying individuals to interview. Ten steps for gathering data were detailed. A section on interview techniques/tips consisted of steps to (a) prepare, (b) begin, (c) conduct, and (d) conclude the interviews. Interviewers were instructed to make copies of a demographic information sheet and the interview questions sheet for each interview. To ensure that all the questions were asked during each interview, the interviewers were asked to check off each question when asked. Four sample letters intended for interviewees were provided to (a) schedule/confirm interviews, (b) express thanks for completing the interview, (c) request a review of transcripts, and transmittal letter for transcript, and (d) extend thanks for return of transcript.

Pre-interview activitiesCoding Themes in InterviewsKnow the purposes for the interview. Develop an agenda or interview guide that you are comfortable with that incorporates the interview questions required by the project. Use an agenda designed to establish a relationship with interviewees that will encourage respondents to give needed information. The agenda will help you track your progress through the interview. Learn enough about the research project and each interviewee to ask intelligent questions and respond to inquiries. Learn the local language, review or learn basic vocabulary related to each respondent's job. Admit you are not an expert. Schedule the interview with sensitivity and flexibility. Schedule a time and place that will enhance the likelihood of getting desired information. Such a place usually requires privacy, quiet, comfort, no distractions, and compliance with the interviewee's wishes for a location and a time. Ethics demand that the interviewee's permission be obtained before a tape recorder is used.

Beginning the interviewBe on time with your visit or call. Since the first moments of an interview are crucial, the initial task is to create an atmosphere that puts the respondent at ease. To build rapport, enlist willingness to corporate, clarify the purpose of the meeting, explain who you are, and how you got involved in this research project. Explain the purpose of the project, its potential impact, why participants were selected, and approximately how long the interview is anticipated to last. When explaining the purpose of the interview, avoid giving information that could bias the study. Allow interviewees to ask any questions. It is during the introduction phase that you are establishing a rapport with interviewees.

When you move out of the introductory phase of your interview into the heart of the inquiry, let the interviewee know by using a transitional phrase: "Now that you have heard about me and the purpose of the project, let me give you a chance to ask questions." After the question/answer period, use a transitional phrase that informs the interviewee that the interview is beginning: "Let's talk about your job and the challenges and successes you have experienced in learning your job."

Conducting the interviewSince the purpose of our interviews was to get details about exactly what respondents do that makes them successful in their jobs, we wanted to ensure that respondents dominated the conversation. Refrain from expressing approval, surprise, or shock at any of the responses. The structure for our interviews was open-ended questions that tend to encourage free-flowing conversation. It is important to listen carefully to answers so appropriate questions can be asked. Note: Sometimes respondents may answer more than one question with a particular response. Therefore, reference to study questions may be useful. Questions can be repeated or their meaning explained in case they are not understood.

Pay attention to the tone of voice and watch for body language. These may yield nonverbal feedback worth noting. Use prompts to keep the interviewee on track or to encourage the interviewee to say a lot or little. "Tell me more about . . .." "Can you think of a specific example of that?" "What did you do then?" "What makes you say that?" "I don't understand what you mean there. Could you explain it in another way." "Whatever you can remember is fine." "Take your time; I'm just going to give you some time to think." Rephrase what a respondent said to clarify and to keep the conversation going. Record the entire interview, starting with the introduction through the conclusion.

Concluding the interviewAfter all the questions have been answered, begin the conclusion phase of the interview. During the concluding phase, allow interviewees to ask any questions and make any comments they deem relevant. Try to provide a verbal summary of what was said as it relates to the purpose of the study. This can be a means of clarifying what has been said and promote a common understanding of the incident described.

Discuss how the interviews contribute to the success of the project. Establish an opening to come back to the respondent for additional information. Inform interviewees of the next stage involving reviewing the transcript. Determine whether the interviewee prefers you to mail the transcript or for you to return in person with the transcript. Express your appreciation for interviewee's contribution.

Theme DevelopmentData Analysis TechniquesA pre-determined set of open-ended questions is usually developed to guide interviews. Transcribed interviews yield a wealth of information that researchers must synthesize into categories to make meaning of the data. While admittedly there are any number of ways to develop categories, a convenient "macro" approach is to begin with the interview questions themselves. Flanagan ( 1982 ) suggested that "the preferred categories will be those believed to be most valuable in using the statement of requirements" (p. 299). In the DPE study, we attempted to determine those factors that effected and affected a primary computer user's organizational adaptability. That purpose required us to determine when current employees felt competent, when they felt incompetent, and what additional training they desired. The frame of reference or primary theme development centered around those skills and abilities relevant to the interviewees' work.

Again referencing the DPE national study, the initial frame of reference was the interview questions. What do you do well? How did you learn how to do what you know? What problems arise in your work? What resources do you consult to solve the problems? When do you feel incompetent? What additional experiences do you desire that may improve your performance? What other roles might you pursue either in this organization or another? As those interviewed spent at least 50% of their time using a personal computer for their work, the frame of reference relevant for these questions focused on computer use.

"The induction of categories from the basic data in the form of incidents is a task requiring insight, experience, and judgment. Unfortunately, this procedure is . . . more subjective than objective. . . . the quality and usability of the final product are largely dependent on the skill and sophistication of the formulator" ( Flanagan, 1982, p. 300 ). As the lead researcher in the DPE national study was most experienced in work-based and qualitative research, she developed the initial categories or codes. She read 11 of the 65 transcripts. Based on a careful analysis of the transcripts, an extensive literature review, and related research experience, 67 codes for the 7 interview questions were developed.

At this same time, the other two researchers also read the first 11 transcripts. The initial code list was distributed among all three researchers for review. This procedure was advocated by Flanagan ( 1982 ). "One rule is to submit the tentative categories to others for review" (p. 300). As a part of this process and subsequent conference calls, six codes were added, making a total of 73 different themes. At that time, prior to all 65 transcripts having been read, the initial list of codes was adopted. Thus, all three of us read all of the first 11 transcribed interviews. The development of initial codes leads to the next step, reaching inter-rater agreement.

Inter-rater AgreementWhen more than one individual collaborates on a qualitative research project, it is critical to the value of the research and the validity of the process that inter-rater agreement on the codes be reached. This may be done in a variety of ways--face-to-face, telephone conferencing, via paper mail. For the DPE national study, we chose two approaches: face-to-face meetings and a series of telephone conference calls. After we had read the first 11 transcripts (17% of the total number, 65), we met to discuss the original 67 codes, plus 6 additions, and to develop consensus on these codes. This process took about two days of conversation, analysis, and revision. An important item to make note of deals with establishing the titles of the codes. Flanagan (1982) notes that "the titles should convey meanings in themselves without the necessity of detailed definition, explanation, or differentiation" (p. 300). A process was developed for reading and coding the remaining 54 transcripts. We agreed that the next step to assure inter-rater agreement was that all transcripts must be read by at least two of us.

As the transcripts were read the number assigned to each code was written in the margin of the transcript next to the narrative corresponding with the code. This facilitated conversation during later conference calls. Once all transcripts were read, we reached consensus or inter-rater agreement, by literally going through every page of all remaining 54 transcribed interviews.

Using a Code SheetWith the use of spreadsheet software, we developed a code sheet. On the top row each interview number was listed; in this case 65 columns. On the left column each of the seven interview questions was listed with all the codes appropriate to the category listed underneath. Each of these codes was numbered with space provided for expansion. A total of 73 rows of themes was listed. When a code appeared in a transcript, a mark was recorded in the appropriate cell on the spreadsheet. It is important to note that once an incident, or code, was noted, no additional marks were recorded for that code. The reason for this is that the purpose was not to determine the number of times the incident occurred in a single interview, but rather that it occurred at least once. (Note: this spreadsheet was transposed later to make each interviewee a row rather than a column in order to allow transfer of data to a statistical package. The main point is to set up a cross-tabulation of interview-by-theme matrix. see Table 1.) Once again, in order to assure accuracy in coding, these code sheets were compared during a number of conference calls. This provided an additional level of inter-rater agreement.

TABLE 1

Spreadsheet Cross Tabulation of Demographic Information Themes by Interviewee

Demographic Information

Themes

ID

No.Sex

Age

Job

TitleYears/

PositionYears/

WorkEducation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1

1

2

5

2

3

1

1

2

1

2

1

1

3

1

1

3

1

1

4

2

3

1

1

4

1

3

4

1

3

2

1

1

5

1

1

3

1

2

1

1

1

1

1

1

6

1

1

2

1

0

1

1

1

1

1

7

1

2

6

1

3

4

1

1

1

1

1

8

1

3

6

3

0

4

1

9

2

2

6

2

2

4

1

1

1

1

The use of the coding sheets in this way can also facilitate later data analysis should one wish to quantify the data, e.g., x% of participants indicated y theme code. This may be useful in presenting macro information as it relates to the research questions that frame the study.

Drawing Conclusions from Critical Incident DataThe purpose of analyzing critical incident interviews is to understand the commonalties among responses. Responses need to be summarized so that dominant or common themes can be identified. There are several software packages designed specifically for this purpose such as NUD*IST and Ethnographer ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). Miles and Huberman provide extensive discussion of what such programs can do. The criterion we used to select a spreadsheet and a standard statistical program, Systat, was familiarity with the software.

Analysis of themes from the critical incident interviews includes rank ordering the frequency of occurrence and identifying themes that were occurring together frequently within the same interviews. A decision needs to be made about the unit of analysis--a single theme or an interview. A theme can occur more than once within a single interview, so if themes are chosen as the unit of analysis, their frequency of occurrence will affect rankings. If a single interview contains several examples of a particular theme, each of these occurrences would affect the frequency of this theme--perhaps giving a single interview a disproportionate amount of weight. To avoid this, the interview (or interviewee) can be considered the unit of analysis. A theme occurring several times within one interview would be counted only once per interview. In our study, the interview was considered the unit of analysis. This choice was made as our intent was to identify rather than quantify themes that emerged from the interviews. Each theme coded in all of the interviews was coded on a spreadsheet as occurring within each interview.

Data PreparationTable 1 shows part of the spreadsheet we used for coding both demographic features and theme occurrence. Notice that each interviewee is a row within the spreadsheet, and the demographic characteristics and themes are the columns. The categories in each demographic area are coded to permit tallying. For example, a "5" in the "Job Title" category for interviewee No. 1 means "Data Entry." These codes are maintained in a codebook so that the report summaries can be linked back to the meaning of the codes. Each theme is identified by a number from 1 to 73 (only portions of which are shown below), and a "1" in a cell means that the theme occurred within the interview. Again, the theme and its code numbers are entered in the codebook so that later the themes, rather than the codes are reported.

Theme FrequencyOnce the interview codes have been entered into the spreadsheet, it is a simple matter of counting and sorting to answer the question about frequency of occurrence of the various themes. It is possible to identify the most commonly occurring theme within each major category of theme type. Table 2 ( Lambrecht et al., 1998 ) shows the presentation of work-related problems for the 65 primary computer users from the national DPE research project.

TABLE 2

"Problems Encountered" - Response Category and Rank Order

Category

Number of Responses

% of

65Rank

OrderTechnical problems: software versions; system down; transcription issues

36

55%

1

Depending on other people for information/work/support

20

31%

2

Using new software

18

28%

3

Getting accurate information

11

17%

4

Dealing with workflow--pressure versus slack

10

15%

5

Knowing expectations

6

9%

7

Prioritizing work from several people

2

3%

8

No problems

1

2%

9

Commonalities Across Interviews

A second question that can be raised about critical incidents is about the commonalties among interviews or whether certain themes tend to appear in the same interviews. Table 3 shows that cross tabulations can help to illustrate visually the number of times pairs of themes occurred in the same interview. In this case the themes are those which arose from asking in the national DPE study what primary computer users did well (14 different themes) and where they learned whatever it was that they did well (12 themes). Notice that the 65 interviews are the unit of analysis. Each cell shows the number of responses on a particular theme that occurred in common from these 65 interviews. For example, Theme #7, a response to "What work was done well?," is the response "Producing high-quality, accurate work." This theme appeared in a total of 23 interviews. Theme #21, a response to the question "Where did you learn what you do well?," is the response "Informal, on-the-job training/observation/picking things up." This theme appeared in 46 interviews. A total of 20 interviews contained both of these themes.

TABLE 3

Cross Tabulation of Themes Across Interviews

Cross Tabulation of Question 1a (Do Well) with Question 1b (How Learned)

Themes 1.a - Do Well --> 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Total 1.b - How Learned Themes 21 20 33 7 9 2 14 20 10 10 5 6 11 2 1 46 22 6 11 3 6 3 4 5 5 3 1 2 3 0 0 14 23 13 21 3 7 4 8 11 6 9 2 2 4 0 1 23 24 2 5 0 2 1 2 2 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 5 25 14 21 4 8 3 5 9 6 6 3 1 5 0 0 24 26 18 24 4 6 1 9 12 9 4 3 5 11 2 0 32 27 3 2 0 2 0 2 3 1 3 0 1 1 0 1 5 28 2 4 0 2 0 3 4 2 3 0 0 1 0 1 5 29 14 20 4 7 2 9 10 6 6 2 5 9 0 1 26 30 2 6 2 3 2 3 2 1 3 0 0 0 0 0 7 31 8 12 5 3 2 5 8 6 5 1 2 5 1 0 15 32 13 24 6 8 2 7 13 7 7 0 2 8 1 1 30 Total 29 47 8 14 5 16 23 12 13 5 8 16 3 1 65 NB Bold Numbers: Number of interviews where both themes appearedThese cross tabulations were obtained by transferring the spreadsheet data partially illustrated in Table 1 into a statistical analysis package with the capability of preparing cross tabulations and carrying out chi-square analysis. Such software is quite common. Systat was used in the recent national DPE research study, but SPSS or Statistix are also commonly used statistical software programs. Once these data have been cross tabulated, chi-square analysis permits the identification of theme clusters that occurred more frequently than would be expected by chance. When this type of analysis is carried out on qualitative data, care must be taken not to give the impression that generalizations can be made to a larger population. This is not inferential statistics. Rather, the chi-square calculation is being used to provide descriptive information about clusters of themes within interviews that may aid in understanding what these themes mean for the specific group of primary computer users interviewed.

Table 4 is an illustration of the chi-square analysis for the two themes mentioned above, #7 and #21 from Table 3.

TABLE 4

Chi-Square Analysis Example

#21 - Informal, OJT #7 - High Quality Work No Yes Total No 16 26 42 Yes 3 20 23 Total 19 46 65 Pearson Chi-Square = 4.509; df = 1, p = 0.034

In Table 3 the cells with bold print are those for which a chi-square value had a probably of .10 or less of occurrence. These are the common interview themes that need to be examined more closely.

The next challenge for researchers is how to present this information in a way that truly summarizes the data and does not overwhelm readers with numbers. There are 168 separate chi-square analysis behind Table 3 above, only 9 of which were statistically significant. The individual chi-square tables provide too much detail. One way to report both the frequencies of common themes across interviews in relation to the total number of themes without presenting a table dense with numbers is to use percents.

Table 5 ( Lambrecht et al., 1998 ) is an illustration of how this was done in the DPE national study being used as an example. The results of each significant chi-square table are reported in a single row. In addition, the ranks of each theme are shown for the two questions reported in this table: "Work that was done well" is being compared with themes from the question "How did you learn what you do well?" The percents reported for each theme are the proportion of interviews (remember, interviews are the unit of analysis) which contained a particular theme which shared that theme in common with interviews containing the second theme in the table row. For example, using the first row of Table 5, "Mastery of Software" was the top-ranked theme for "Work that was done well." Of all the interviews that contained this theme, 45% also contained the theme of "Self-Taught," the 5th-ranked theme "Self-Taught" for "How did you learn what you do well?" Correspondingly, 88% of the interviews that contained the theme "Self-Taught" were the same interviews that said what they did well was "Mastery of Software." While the number of common responses was 21 (see Table 3 for Themes #2 and #25), 47 different interviews contained the "Mastery of Software" theme (21/47=45%), and 24 interviews contained the theme "Self-Taught" (21/24=88%).

TABLE 5

Primary Computer Users Cross Tabulations: Significant Relationships between Work Done Well and How It Was Learned

Table 5 Above Cont'd: *C/R = Common Responses

Rank Q: What is an Example Of What You Do Well % of Common Responses (C/R) Rank Q: How Did You Learn This? % of Common Responses (C/R) 1 Mastery of Software 45% 5 Self Taught 88% 2 General Office Work 62% 2 Formal Classroom Training 56% 3 High Quality, Accurate Work 35%

C/R7 Access to Individuals 53%

C/R3 High Quality, Accurate Work 87%

C/R1 Informal O-J-T 43%

C/R5 Interpersonal Skills 68%

C/R2 Formal Classroom Training 34%

C/R8 Interpret Expectations 75%

C/R2 Formal Classroom Training 28%

C/R8 Interpret Expectations 50%

C/R7 Access to Individuals 40%

C/R9 Interpret Computer Generated Information 75%

C/R3 Prior Formal Education 20%

C/R9 Interpret Computer 63%

C/R7 Access to Individuals 33%

C/R

When there are several key questions from a critical incident study with several resulting themes, the data analysis takes a little time to organize and present in a well-synthesized final report. The recent national DPE study involving primary computer users had four main questions with several subquestions. A total of 73 themes emerged for the 65 interviews. Once the key tables have been developed to synthesize the theme rankings and relationships, the study conclusions become a matter of interpreting what they mean in response to the key questions in the study.

SummaryDrawing conclusions from qualitative research projects is similar to drawing conclusions from quantitative research projects in that both require interpretation. It is important not to mistake a restatement of the findings for the conclusions of the study. Rather, it is necessary to interpret the findings while considering both the original research questions and the conceptual base for the study.

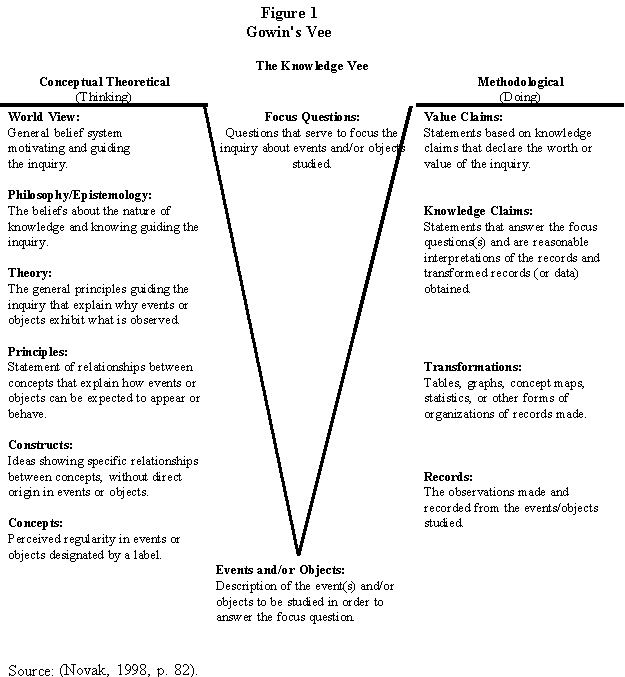

What does the theory, the conceptual base, allow you to make of the findings? To aid in answering this question, a visual aid such as Gowin's Vee is helpful ( Novak, 1998 ). The question of a research project is the Focus Question at the top of the Vee (see Figure 1). At the bottom of the Vee are the events or objects, the data, collected in a study to answer the focus question. What one says about the data depends upon how the findings are presented (the Transformations of the original data Records) which permit researchers to make knowledge claims based on the conceptual base described on the left side of the Vee. This conceptual base exists whether or not the researcher makes his or her assumptions explicit. However, if these assumptions and the conceptual base are not made explicit, it can be difficult to know what to make of findings-how to explain what has happened.

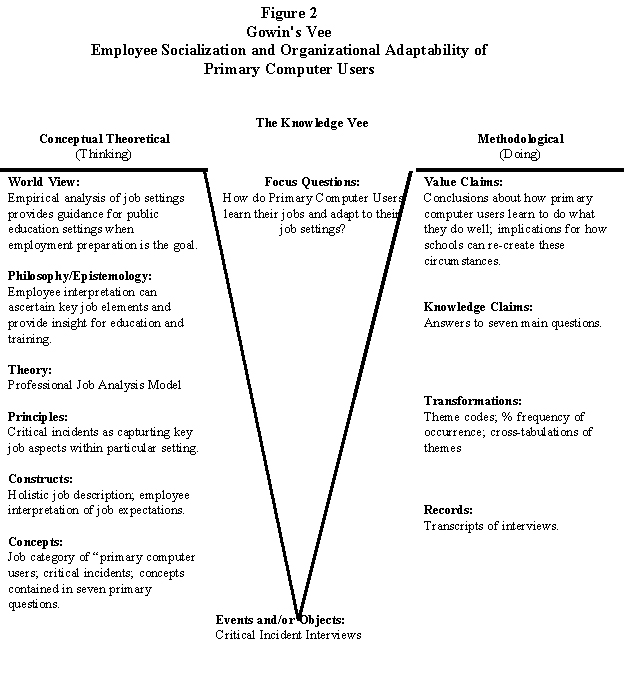

Application of Gowin's Vee ( Novak, 1998 ) to the DPE research project is depicted in Figure 2. The Focus Question at the top provided the framework for the investigation. The critical incident interviews provided the objects to be studied. The theme codes and cross tabulations provided the foundation for the knowledge claims and subsequent value claims. The left side of Gowin's Vee provides a framework for the conceptual or theoretical base for the study, the professional job analysis model.

References

ReferencesAs demands for research that is both theory-based and real-world relevant increase, the consideration and use of a variety of research methods will be required. The critical incident technique is one such strategy to investigate issues relevant to job behavior in terms of the social job context. We have provided guidelines and examples drawn from a recent research project to demonstrate how the CIT may be used.

While other strategies are available, the CIT is an excellent strategy for job behavior analysis which moves far beyond the traditional list development of needed skills and knowledge. Research study participants' own words provide greater clarity and specificity than any checklist of job skills or tasks to which they may respond. This technique allows researchers to more clearly capture those incidents critical to job behavior.

AuthorsAmerican Institutes for Research (AIR). (1998, April). The critical incident technique. AIR Web Page . [On-line]. Available: www.air.org/airweb/about/critical.html .

Bacchus, R. C., & Schmidt, B. J. (1995). Higher-order critical thinking skills used in banking. NABTE Review, 22 , 25-28.

Bailey, T. (1990). Changes in the nature and structure of work: Implications for skill requirements and skill formation (MDS- 007). National Center for Research in Vocational Education University of California at Berkeley.

Bailey, T., & Merritt, D. (1995, December ). Making sense of industry-based skill standards (MDS-7&7). National Center for Research in Vocational Education, University of California at Berkeley.[On-line]. Available: http://ncrve.berkeley.edu/AllInOne/MDS-777.html .

Borg, W. R., & Gall, M. D. (1989). Educational research: An Introduction (5 th ed.). New York: Longman.

Di Salvo, V. S., Nikkel, E., & Monroe, C. (1989). Theory and practice: A field investigation and identification of group members’ perceptions of problems facing natural work group. Small Group Behavior, 20 (4), 551-567.

Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychologic Bulletin, 51 (4), 327-358.

Flanagan, J. C. (1982). The critical incident technique. In R. Zemke & T. Kramlinger (Eds.), Figuring things out: A trainer’s guide to needs and task analysis (pp. 277-317). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Finch, C. R., Gregson, J. A., & Faulkner, S. L. (1991, March). Leadership behaviors of successful vocational education administrators (MDS- 435). National Center for Research in Vocational Education University of California at Berkeley.

Finch, C. R., Schmidt, B. J., & Moore, M. (1997, October). Meeting teachers' professional development needs for school-to-work transition: Strategies for success (M DS-939). National Center for Research in Vocational Education, University of California a Berkeley. [On-line] Available: http://vocserve.berkeley.edu/AllInOne/MDS-939.html.

Fraenkel, J. R., & Wallen, N. E. (1996). How to design and evaluate research in education (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Gay, L. R., & Diehl, P. L. (1992). Research methods for business and management . New York: Macmillan.

Lambrecht, J. J. (1999). Developing employment-related office technology skills (MDS 1199). National Center for Research in Vocational Education, University of California at Berkeley.

Lambrecht, J. J., Hopkins, C. R., Moss, J., Jr., & Finch, C. R. (1997, October) Importance of on-the-job experiences in developing leadership capabilities . MDS-814. Berkeley: National Center for Research in Vocational Education, University of California at Berkeley.

Lambrecht, J. J., Redmann, D. H., & Stitt-Gohdes, W. L. (1998, unpublished). Organizational socialization and adaptation: Learning the ropes in the workplace by primary computer users . (Research report). Little Rock, AR: Delta Pi Epsilon.

Merritt, D. (1996, April). A conceptual framework for industry-based skill standards. Centerfocus , No. 11. [Online version available at URL: http://ncrve.berkeley.edu/CenterFocus/CF11.html ]

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook : Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Novak, J. D. (1998). Learning, creating and using knowledge: Concept maps as facilitative tools in schools and corporations Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rossett, A., & Arwady, J. W. (1987). Training needs assessment . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology.

Schmidt, B. J., Finch, C. R., & Faulkner, S. L. (1992). Teachers' roles in the integration of vocational and academic education (MDS-275). National Center for Research in Vocational Education, University of California at Berkeley.

Schmidt, B. J., Finch, C. R., & Moore, M. (1997, November). Facilitating school-to-work transition: Teacher involvement and contributions. (MDS-938). National Center for Research in Vocational Education, University of California at Berkeley. [Online at URL: http://vocserve.berkeley.edu/AllInOne/MDS-938.html ]

Siegel, L., & Lane, I. M. (1987). Personnel and organizational psychology (2nd ed.). Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Zemke, R., & Kramlinger, T. (1982). Figuring things out: A trainer’s guide to needs and task analysis . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

WANDA L. STITT-GOHDES is Associate Professor, The University of Georgia, 225 River's Crossing, 850 College Station Rd., Athens, GA 30602-4809. [E-mail: WLSG@arches.uga.edu ] Her research interests include teacher education, relationship between instructional styles and learning, and business education.

JUDITH J. LAMBRECHT is Professor and Coordinator, Business and Industry Education, Dept. of Work, Community, and Family Education, University of Minnesota, 1954 Buford Avenue, Rm. 425, St. Paul, MN 55108. [E-mail: jlambrec@tc.umn.edu ] Her research interests include instructional systems and related technology, qualitative research, and business education.

DONNA H. REDMANN is Associate Professor, School of Vocational Education, Louisiana State University, 142 Old Forestry Bldg., Baton Rouge, LA 70803. [E-mail: voredm@unix1.sncc.lsu.edu ] Her research interests include human resource and organizational development and business education.