ALAN v31n1 - The Artistic Identity: Art as a Catalyst for 'Self Actualization' in Lois Lowry's Gathering Blue and Linda Sue Park's A Single Shard

Janet Alsup

The Artistic Identity:

Art as a Catalyst for “Self Actualization” in Lois Lowry’s Gathering Blue and Linda Sue Park’s A Single Shard

Exupéry’s The Little Prince begins this way:

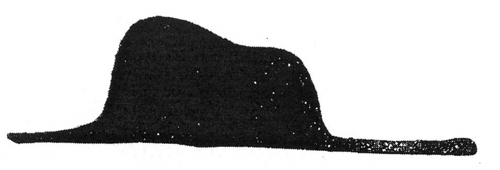

“Once when I was six I saw a magnificent picture in a book about the jungle, called True Stories. It showed a boa constrictor swallowing a wild beast. Here is a copy of the picture. In the book it said: ‘Boa Constrictors swallow their prey whole, without chewing. Afterward, they are no longer able to move, and they sleep during the six months of their digestion.’ In those days I thought a lot about jungle adventures, and eventually managed to make my first drawing, using a colored pencil. My drawing Number One looked like this:

In the book it said: ‘Boa Constrictors swallow their prey whole, without chewing. Afterward, they are no longer able to move, and they sleep during the six months of their digestion.’ In those days I thought a lot about jungle adventures, and eventually managed to make my first drawing, using a colored pencil. My drawing Number One looked like this: I showed the grown-ups my masterpiece, and I asked them if my drawing scared them. They answered, ‘Why be scared of a hat?’ My drawing was not a picture of a hat. It was a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. Then I drew the inside of the boa constrictor, so the grown-ups could understand. They always need explanations. My drawing Number Two looked like this:

I showed the grown-ups my masterpiece, and I asked them if my drawing scared them. They answered, ‘Why be scared of a hat?’ My drawing was not a picture of a hat. It was a picture of a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. Then I drew the inside of the boa constrictor, so the grown-ups could understand. They always need explanations. My drawing Number Two looked like this: The grown-ups advised me to put away my drawings of boa constrictors, outside or inside, and apply myself instead to geography, history, arithmetic, and grammar. That is why I abandoned, at the age of six, a magnificent career as an artist [. . .].” ( 2 )

The grown-ups advised me to put away my drawings of boa constrictors, outside or inside, and apply myself instead to geography, history, arithmetic, and grammar. That is why I abandoned, at the age of six, a magnificent career as an artist [. . .].” ( 2 )The narrator in The Little Prince isn’t encouraged to explore his creativity as a child, and so, as he grows older, he accepts and participates in the comparatively boring, literal world of adults—at least until he meets that strange visitor from another world—the little prince. One message that emerges from this book, first published in 1943, is that sometimes the ideas and beliefs of children express a sort of imaginative wisdom that eludes adults. In the book, the little prince teaches the narrator to be a child again by asking him to draw things—specifically, a sheep, a muzzle, and a fence for his flower—so that he can take them into outer space and improve his very small world. When the narrator draws these things, the assumption is that they become real because they are drawn; or, in other words, drawing and reality are one and the same. Similar to the cartoon roadrunner who draws a railroad tunnel on the side of a mountain into which he escapes, the drawing becomes real—at least for those who understand the drawing’s potential. (For the coyote, of course, the drawing is always simply lines on the very hard and painful side of a mountain.)

Two young adult novels, Linda Sue Park’s A Single Shard (2001) and Lois Lowry’s Gathering Blue (2000), reclaim and elaborate artistic production as a metaphor for growing up or coming of age in a very difficult world. Similar to Exupéry’s work, Park’s and Lowry’s books contain young, artistic characters who find the act of artistic creation central to their growing understanding of the worlds in which they live, as well as to their developing identities. The main character in Park’s novel, Tree-ear, is yearning to be a potter in 12th century Korea despite the fact that he’s an orphan, and potters are only allowed to apprentice biological children. Similarly, Kira, the teenage girl in Lowry’s book, is a gifted weaver imprisoned and required to weave scenes on a sacred robe that, supposedly, accurately records the past and foretells the future. Like the narrator of The Little Prince , the adolescent main characters of these novels find that adults tend to discourage or place roadblocks in their artistic paths or even fail to understand art as synonymous with beauty and imagination, seeing it, instead, as a means to some materialistic end; however, despite these roadblocks, the adolescent characters pursue their aesthetic callings successfully, and, in embracing art as central to their lives, they are able to come to an enriched understanding of the complexity of their identities, or the multiple subjectivities or selves that make up these identities. The authors of A Single Shard and Gathering Blue present artistic creation as a metaphor and a catalyst for adolescent identity formation by creating rich characters whose experiences as artists pave the way for their cognitive, social, emotional, and psychological growth into well-balanced, and, one might even say, self-actualized adults.

Jean Piaget described part of this growth as the development of the ability to think more abstractly and about issues and ideas not concretely related or immediately relevant to self. Engaging in the “flow” of artistic experience might be one way of initiating such movement away from an egocentric, concrete understanding of the world and the self and toward a more abstract and de-centered view of reality that allows an adolescent to generalize, hypothesize, and empathize with others. Mihaly Csikszentmihaly defines flow as “the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it” (4). Becoming completely immersed in the act of creation or art could help an adolescent forget, at least for a brief time, her concerns with the material realities of her life, such as her body, her peer relationships, or family problems. Such brief times of immersion in the act of creation could provide short-term practice in abstract thinking (for example, considering the aesthetic effect of a particular brushstroke on a hypothetical audience), as well as an escape from day-to-day stresses.

In A Single Shard Tree-ear experiences such flow early in the novel, as he begins to yearn for the potter’s life. In the following passage he is described creating a small, molded clay monkey that he eventually gives to Crane-man, Tree-ear’s caregiver since he was orphaned as an infant: “Tree-ear found that he had enjoyed the incision work. He had spent hours on the details of the monkey’s features, inscribing them with progressively finer points. On seeing the monkey after it had been fired, Tree-ear felt a quiet thrill” (106). While making the monkey, Tree-ear is engaged in the flow of the artistic experience.

Similarly, Kira in Gathering Blue feels a sense of magic and lost time when she is engaged in her weaving. Lowry writes:

The threads began to sing to her. Not a song of words or tones, but a pulsing, a quivering in her hands as if they had life. For the first time, her fingers did not direct the threads, but followed where they led. She was able to close her eyes and simply feel the needle move through the fabric, pulled by the urgent, vibrating threads (45).Kira, like Tree-ear, is lost in her work; she is in a state of flow. The process of creating art is affecting her psyche and beginning to be an important part of her identity.

Morris Rosenberg describes the process of adolescent development in a way similar, but not identical, to Piaget. According to Rosenberg, one change is in the content of the adolescent’s self-conceptions over time. Rosenberg describes this transition as the shift from an emphasis on the social exterior to an emphasis on the psychological interior. In particular, the younger adolescent tends to think of the self in terms of overt, external dimensions; the older adolescent tends to emphasize more internal, covert, psychological dimensions. Additionally, he argues that the developing individual understands self in varying ways, beginning with a perception of self as a simple, global construct and developing to one that is increasingly differentiated and multi-faceted. That is, the ways he thinks of himself begin to become more complex and multi-dimensional. His identity is understood less as singular and unitary and as a more variable, context-specific representation of self.

We see such realizations happening for Tree-ear and Kira; for example, at the end of the book, Tree-ear makes a difficult journey to deliver some of his teacher’s pots to the emperor so that his teacher can get a royal commission. He does this simply because he promised he’d do so, without expecting anything for himself. This is a change from the beginning of the novel when Tree-ear only chooses to work for Min, the master potter, because he hopes it will result in pottery- making lessons. Likewise, Kira changes from being a girl who understands herself as inherently linked to her mother in the eyes of the community and therefore as someone inherently vulnerable without the assistance of others; by the end of the book, she chooses to follow her artistic gifts at great personal risk and allows them to guide her to make decisions for the future of her entire community. Both of these examples show Tree-ear and Kira moving away from a concrete, egocentric worldview and toward an ideology that values actions with an ethical or emotional justification and sometimes nebulous or uncertain results. These are also actions they could not previously have imagined themselves engaging in, actions that are in response to unforeseen problems. In other words, specific life events precipitated the emergence of personality characteristics they didn’t know they possessed.

Individuation, according to Carl Jung, is a process of developing the individual personality and establishing one’s true identity. It can be seen as synonymous with self-actualization. Lisa Schade writes about Jung’s theories:

According to Jung, the self is the whole of consciousness, of psyche, of an individual . . . the goal of the individual is to reach a balance or recognition of the different aspects of the self; he called the process of understanding the self-individuation or self-actualization. An individual becomes conscious of the vast reaches of the self. (12-13)A Single Shard and Gathering Blue show two characters coming to a sense of identity, a sense of self that is richer, more complex, and more varied than that with which they begin. This gets them closer to selfactualization, in Jung’s sense. Through identification as artists, Tree-ear and Kira begin to understand themselves, their place in their families and communities, and how their role as artists will become a part of their lives that may not constitute their complete identity, but will be one important dimension of it. In other words, they are becoming aware of Jung’s “vast reaches of the self.” For example, in A Single Shard , once Tree-ear sees himself as a potter, he begins to form a plan for what role his art might play in his life and in the life of his community: “How long would it be before he had skill enough to create a design worthy of such a vase [the thousand cranes vase]? One hill, one valley [. . .]. One day at a time, he would journey through the years until he came upon the perfect design” (148).

Tree-ear begins to see his life as a journey, in which art will play a role. But at the end of the novel, he has an adoptive family, and he knows that learning his craft to his satisfaction will not come quickly or easily. He has developed a much more complex and realistic view of being a potter, and an adult, than he had at the beginning of the book when all he wanted were lessons from Min in exchange for manual labor. Kira also takes on the artistic identity, and it also enables her to come closer to self-actualization. Lowry writes:

It was the same question that she and Thomas had discussed the day before. And the answer seemed to be the conclusion they had reached: they were artists, the three of them. Makers of song, of wood, of threaded patterns. Because they were artists, they had some value that she could not comprehend. Because of that value, the three of them were here. (153)Once Kira makes the decision to resist the authority of the council and weave the robe with the images and designs she wants to include, she no longer feels powerless and childlike, but, instead, powerful and purposeful. She claims her creativity and decides to embrace it and act through it to improve her life and her community by weaving a future full of happiness, not fear, into the robe. Of course, she also knows this will not be easy; however, she makes the difficult choice anyway, even though it will mean temporary separation from her newly found father. Roberta Seelinger Trites writes, “Power is a force that operates within the subject and upon the subject in adolescent literature; teenagers are repressed as well as liberated by their own power and by the power of the social forces that surround them in these books” (7). In Kira’s case, she first succumbs to the oppressive politi- cal system in which she lives and consents to use her artistic gifts to assist the leaders with their policies of intimidation and intellectual control. Later, with the help of peers and family, she discovers her own power and uses her position as weaver of the sacred robe to change the society in which she lives.

Like the narrator in The Little Prince , Tree-ear and Kira find that by creating art and by claiming an identity as artists, they have been able to come to a more complex and satisfying understanding of their individual and cultural identities. Each chooses to use his or her art to help fellow humans or contribute to community life in their respective contexts; each also shares his or her art with others in purely generous and loving ways. Trites writes,

“The basic difference between a children’s and an adolescent novel lies not so much in how the protagonist grows . . . but with the very determined way that YA novels tend to interrogate social constructions, foregrounding the relationship between the society and the individual, rather than focusing on Self and self-discovery” (20).Tree-ear and Kira do interrogate, and eventually come to terms with, the relationship between their artistic identities and the societies in which they live.

In The Principles of Art R.G. Collingwood states,

“The artist must prophesy not in the sense that he foretells things to come, but in the sense that he tells his audience, at risk of their displeasure, the secrets of their own hearts. Art is the community’s medicine for the worst disease of mind, the corruption of consciousness” (336).The characters in both books not only change individually, they also change their communities by disrupting this “corruption of consciousness” that exists in the adult worlds in which they live. Tree-ear is able to re-introduce a sense of fairness to the evaluation of the work of Korean potters of his time, as well as help an aging master potter establish a relationship with a young apprentice, despite Korean tradition. Similarly, Kira confronts an unfair political system and, in a sense, uses her art as an antidote to its poisonous ideologies.

Park ends her book by telling the reader about “The Thousand Cranes Vase” currently on display at the Kansong Museum of Art is Seoul, Korea. Even though Tree-ear is, of course, a fictional character, the fictional merges with fact as Park suggests that perhaps such a vase, depicting the crane as a tribute to his beloved Crane-man, might have been made by a young potter like Tree-ear. One of the points I think Park is trying to make is that Tree-ear’s art may exist over 800 years after its creation; it might be on display in a museum; it might even be the impetus for the writing of a young adult novel. His art has not only brought a sense of personal satisfaction and self-understanding to Tree-ear; it has touched generations of people who came after him.

As the narrator in The Little Prince will never forget what the visitor taught him about the value of the imagination, Tree-ear and Kira are forever changed by their realization that they are creative, imaginative beings—they know they are artists. In a day and age when art, along with music, is being taken out of many secondary school curricula because of lack of funding, the lessons Park and Lowry convey carry even greater significance, both for the adolescents who might read their novels and for the adults who can, if they try hard enough, see through the hat to find the boa constrictor digesting an elephant.

Janet Alsup is an Assistant Professor of English Education at Purdue University. Her scholarly interests include critical approaches to young adult literature, the professional identity development of preservice English teachers, ethical issues in qualitative research, and critical pedagogies and literacies.

Works Cited

Collingwood, R.G. The Principals of Art . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958.

Csikszentmihaly, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience . New York: Harper Perennial, 1990.

Lowry, Lois. Gathering Blue . New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Park, Linda Sue. A Single Shard New York: Clarion, 2001.

Piaget, Jean. Ed. trans. Robert L. Campbell. Studies in Reflecting Abstraction , New York: Psychology Press, 2001.

Rosenberg, Morris. “Self-Concept from Middle Childhood Through Adolescence.” Psychological Perspectives on the Self, volume 3. Eds. J. Suls and A.G. Greenwald. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1986.

Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de. The Little Prince . New York: Harcourt, 1943.

Schade, Lisa. “The Archetypal Approach.” Diss., Western Michigan University, 2002.

Trites, Roberta Seelinger. Disturbing the Universe: Power, and Repression in Adolescent Literature . Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2000.