Professional Resource Connection

with guest contributors Jeff Copelandand Jerome Klinkowitz

Inman’s War:

Genre Jumping Brings to Life the Letters of an African American WWII Soldier (Plus, a Bibliography of African American WWII Literature Suitable for YA Readers)

I have written about the literature of WWII in this space before (“Finding Small Press and Self-Published Books about WWII.” Volume 32, Number 1, Fall 2004), and I will probably do it again if the editors let me. That is because I have seen so many great middle school teachers attach units of robust and engaging literature of WWII onto a common reading of the play The Diary of Anne Frank found in many middle school literature anthologies. More recently I have seen how effective both middle school and high school librarians and English teachers have become in spreading the word to their social studies colleagues about the value of their students reading book-length fiction and nonfiction texts, especially texts about WWII. This time I am offering resources about the literature of WWII as it depicts African-Americans.

I am inspired in this effort by having just finished Inman’s War: A Soldier’s Story of Life in a Colored Battalion in WWII by Jeffrey S. Copeland. You are going to be hearing about this book from many sources, if you haven’t already. It was a moving read, and it is a great book for young adults. In my opinion, it achieves this status by blurring the lines of genre. The book is largely a first-person narrative constructed from the letters of Inman Perkins (a WWII GI) and the extensive research that grew out of those letters. It is not fiction and it is not non-fiction, and the text of the book is a first-person narrative rather than a collection of letters.

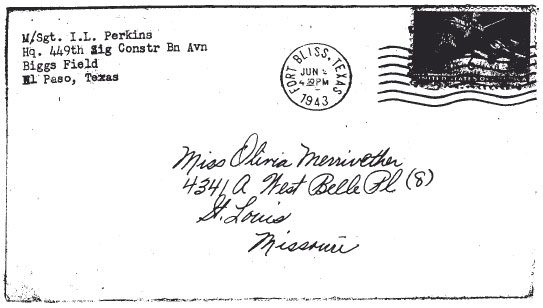

Below, distinguished literary scholar Jerome Klinkowitz offers a review of Inman’s War. That review is followed by something you cannot find within the pages of Inman’s War— a photocopy of one of Inman Perkins’ letters to his wife, Olivia, accompanied by notes that show Copeland planning how to spin the letter into his first-person narrative. This column concludes with an annotated bibliography of books about African-Americans in WWII compiled and introduced by Inman’s War author and professor of young adult literature Jeffrey Copeland. But first I want to entice you with the story about the writing of Inman’s War. The truth is stranger than fiction.

young African-American

WWII soldier to his wife.

Some were from the wife

to the soldier—nearly 150

letters written between

fall 1942 and late spring

1944.

Once upon a time, in the fall of 2002, Jeffrey Copeland, whose area of YA literature is the lives of poets who write for young adults, and who had little past experience with artistic or creative writing, stumbled across an old suitcase full of letters at a flea market in Belleville, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from his hometown of St. Louis, Missouri. The letters were from a young African-American WWII soldier to his wife. Some were from the wife to the soldier—nearly 150 letters written between fall 1942 and late spring 1944. The reading of those letters sent Copeland on an odyssey. He went to the school in St. Louis where the husband and wife had taught and was told, “The records might be stored downtown somewhere.” But on the way out of the building the elderly custodian who had overheard said, “I know about Inman and Olivia Perkins.” Copeland learned that some of that schools students of the era in which the Perkins taught were quite well known. Later, standing in line after a lecture to meet the great Dick Gregory who had been one of Olivia’s students, Copeland showed Gregory a picture of Inman in uniform standing next to Olivia on the steps of the high school and asked him if he remembered these people. Recognizing his teacher Gregory got misty-eyed, and when he learned of the letters and the book in-progress asked if he could write the introduction. Copeland traveled to several repositories of military archives only to learn that he was the first person since 1945 to read the accounts of the battalion Perkins lead. And there is more to the story of writing this book that you can read about in Copeland’s introduction to his annotated bibliography below.

When I read Inman’s War, I thought it was perfect for young adult readers as well as for anyone interested in WWII or the African-American experience in the Midwest in the 1940’s. It would be a great book for high school history students or college students in African-American Studies. I hope The ALAN Review readers keep teaching those important units on WWII and encourage individual students and reading groups to read widely in the scores of great books on the subject. I hope that the following review and bibliography will help you round out your classroom and library collections.

Review of Inman’s War

Inman’s War: A Soldier’s Story of Life in a Colored Battalion in WWII. By Jeffrey S. Copeland. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2006. 366 pp. Paperback. $17.95

Reviewed by Jerome Klinkowitz, Professor of English, University of Northern Iowa

Inman Perkins was a science teacher at Charles Sumner High School in St. Louis, Missouri. There he met and married Olivia Merriwether, who taught science. In 1942, he joined the United States Army Air Force, serving in a Signal Construction Battalion that saw combat in Italy—at Anzio, which saw some of the fiercest and costliest fighting of World War II. As a teacher, he was a leader, and became even more of one in the service. In doing so, he quickly attained the rank of First Sergeant. Why not higher? Because he was an African American. His unit was segregated; officers’ commissions were limited to whites. Being First Sergeant was as far as Inman Perkins was allowed to go.

To his men, however, he might as well have been a general, a highly respected and beloved one at that. Disregarding military custom, they saluted him as if he were General Eisenhower himself. And while it is the Eisenhowers and Pattons who have had their stories told by leading historians, it is Sergeant Perkins who (with scholar Jeffrey S. Copeland’s help) tells his own. During his training in the U.S. and while stationed abroad, Inman wrote his fiancée (and soon, secretly, his wife) Olivia nearly 150 letters, which she saved for the rest of her life. For Inman’s War those letters are used to create an autobiographical narrative that tells an important story of what some have called America’s Greatest Generation, a story that now has a rainbow hue.

of soldiers; she continued

as a teacher (of some

remarkable students,

including Arthur Ashe,

Tina Turner, Chuck Berry,

and Dick Gregory, the last

of whom has honored her

with an introduction to

this volume).

Inman Perkins’ tale could have been one of limitations: of having to teach only African American students, themselves restricted to a segregated high school; having to marry Olivia in secret, because at that time in that school district, married women were not allowed to continue their careers as educators; of having to serve in what was formally named as a “colored” battalion (other battalions were colored, too, but their color was white); and having to discover the racial attitudes of the American South, after being raised in middle class circumstances in Des Moines, Iowa. Thankfully, neither Inman nor Olivia let themselves be hamstrung by these obstacles. He persevered as a leader of soldiers; she continued as a teacher (of some remarkable students, including Arthur Ashe, Tina Turner, Chuck Berry, and Dick Gregory, the last of whom has honored her with an introduction to this volume). Succeeding against the odds has become popular lore for the attractiveness of their generation, and the materials of Inman’s War substantiate the claim people of this era make for our sympathy and admiration.

Because the materials of Inman Perkins’ letters have been woven into such an appealing story, readers can get a true sense of what life was like for a pair of two still relatively young people in the years just before and during World War II—life not just from an African American perspective, but from viewpoint of people born into a world on the threshold of great, even monumental change— an era, in other words, somewhat like our own time of millennial fears and expectations. Because both Inman (in the service) and Olivia (in high school) are devoting themselves to informing and inspiring others, their leadership makes issues of the day all the more critical. Inman, for example, has to teach men how to drive Army vehicles, and some of these men have never sat in the front seat of a car! He stands up for them when custom would restrict their Rest & Relaxation time to the base and its environs, instead of the more exciting prospects of some time off in Mexico. He guides them through minefields—some laid by Germans, other (metaphorically, but no less real in their effect) by racial custom in our own military.

That Inman led men in a Signal Construction Battalion proves significant. His unit endured all the risks of combat forces, yet with a different mission: not to destroy but to build. They supported troops, but also civilians. One of the book’s most impressive episodes comes near the end, when Inman directs the rescue of some villagers trapped in a bombed building. It’s a tricky task, putting his men at great risk. He must commandeer building supplies and improvise a structural support that allows his men to climb through the teetering rubble (past an unexploded bomb) and bring the survivors to safety. Instead of killing Germans, Inman’s battalion saves Italians. Needless to say, they are hailed as heroes.

With full respect for Inman Perkins’ story, Jeffrey S. Copeland effectively “channels” himself as the teacher/sergeant’s voice, taking letters and developing them into a coherent, compelling story. That many of them were love letters does not detract in the least. Instead, it gives the story its fullest dimension. Inman loved Olivia, and she him. He loved his men, and they him. And whether at war or in the classroom, Mr. and Mrs. Perkins loved their country, making it better by everything they did.

***

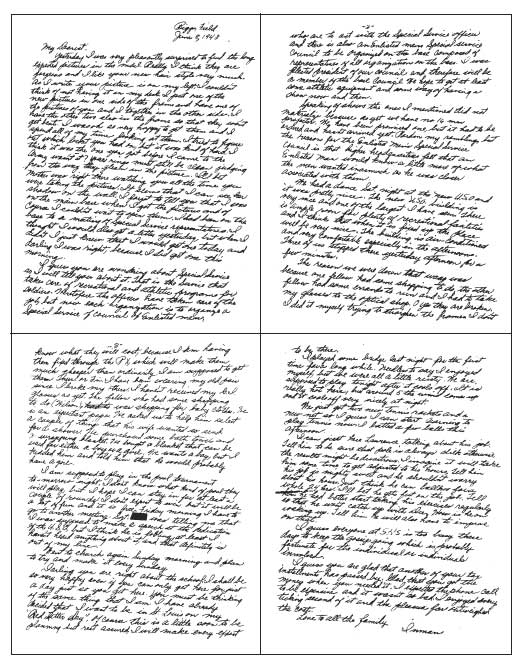

What Jerome Klinkowitz means by using the term “channeling” can be seen by considering the Inman Perkins letter in Figure 1, Copeland’s notes on the letter, and a quote from the book that is connected to the letter and the notes.

Here we see Copeland making notes to create the first-person narrative out of the letters.

Notes—Letter, June 8, 1943:

- First of all, Inman talks in this letter about the “Special Services” organization set up for all things related to recreation and athletics at Ft. Bliss in El Paso, Texas. He was actually elected President/representative of his segment of the council (representing the 449th). What he did not know at the time he wrote this letter was that while he was allowed to be part of the overall council, recreation and athletics were still to remain segregated on the base. A little over a month later he wrote Olivia about his surprise in discovering this fact. In other words, he was invited to the table, but he wasn’t invited to eat ...

- He also talks here about a movie projector that was supposed to be given to his outfit. This became a running joke between Inman and Olivia in their letters because the 449 th never got one through normal channels. It was just one of many promises made to the 449th that never materialized. Eventually, his friend, Williams, had to go to the other side of the base to “borrow” one.

- In this letter Inman talks about the new U.S.O. club (what Inman’s battalion called the Service Club). Although he says in this letter he doubted a rumor from another sergeant that Inman would be giving a talk at the dedication, he did end up doing exactly that. However, after all the pomp and circumstance surrounding the dedication died down, Inman’s battalion was allowed the use of the facility just one night per week. This limited use eventually led to one of the major conflicts between the men of the 449 th and others on the base (described in the book).

- The “Red Letter Day” he is talking about in the letter was “Inman Perkins Day” at Charles Sumner High School in St. Louis, Missouri, where he had taught before the war. Unfortunately, the “day” did not coincide with his leave, so those at Sumner held it without him present. Olivia said a few words on his behalf.

joke between Inman and

Olivia in their letters

because the 449 th never

got [a movie projector]

through normal channels.

It was just one of many

promises made to the

449 th that never materialized.

Eventually, his friend,

Williams, had to go to the

other side of the base to

“borrow” one.

The voice of Inman Perkins telling his own story in the text is amazing as we see on page 234 of Inman’s War. This scene takes place in the office of the white colonel in charge of the colored battalion where Inman, a master sergeant, spends some of his time as an administrative assistant.

The most anticipated night of the week was Thursday night. Thursday night was our one and only night to use the base Service Club. . . . The Service Club was popular with the men because it had brand-new pool tables with smooth felt, Ping-Pong tables that were level, shuffleboard tables of regulation size, and card tables and chairsthat didn’t collapse when leaned on or sat in. The Club also had a jukebox stuffed with the latest Glen Miller and Benny Goodman records and a large dance floor right next to it. . . . We had our own recreation area in the barracks and had converted part of the motor pool into our own version of a Service Club, but it wasn’t even close to being in the same league as the base club. For the men, the base club was like entering the gates of Shangri-La.

Colonel Ellis had stuttered and stammered that first week we came to camp when he explained to me that our battalion [the only colored battalion on the base] would be allowed to use the club only on Thursday evenings. I asked it all of the other groups on the base had special nights as well. His response was, “Well, others use the club the rest of the time.”

I was sorting files at the time and pretended not to hear him. Without looking up, I said, “I’m sorry, Sir. I was looking for something and missed what you were saying. So, other groups on the base have their own special nights, too?”

“Sort of, They all . . . that is . . . it’s used by . . .” he said, struggling for words and chopping sentences in two. Finally he just blurted out, “Well, it’s restrict . . .”—and he minute he said it I saw out of the corner of my eye his eyes widen as he realized what he had started to say. He quickly shouted out, louder than he probably meant to, “I mean it’s reserved the rest of the week!”

He paused a minute, taking his glasses off to wipe them with his handkerchief, and added, softly, “Our battalion gets to use it Thursday nights, OK?”

“If you say so, Sir,” was all I could think of to say. I understood perfectly what he meant. Perfectly.

Inman’s War reads like a novel, but it is more and less than a novel. It is A Soldier’s Story of Life in a Colored Battalion in WWII.

***

Chasing Ghosts: African-American Contributions in World War II

Finally, Jeffrey S. Copeland offers a few words of his own, as well as a bibliography (see p. 00):

The journey started on a hot and dusty Saturday morning at an outdoor flea market in Belleville, Illinois. Piles of old letters were stacked haphazardly in a suitcase balancing precariously on the edge of a dealer’s table. I picked up a couple of the letters and started reading them. I immediately discovered two things. First, the letters were World War II vintage. Second, the voice in the letters touched something deep within me. Most of the letters were from a Sergeant Inman Perkins to Olivia Merriwether of St. Louis, Missouri. The more I read into the letters, the more my mind began racing. Who were these people—and what had happened to them? I purchased the letters and began a quest that I could not have imagined in my wildest dreams.

When I got back home that same afternoon, I put the letters in chronological order and started reading through them. It was only then I realized Sergeant Inman Perkins was a member of what, at the time of World War II, was called a “Colored Battalion,” a label that was, sadly, fitting for many of that era because of the segregation that was a fact of life in the armed forces. Sergeant Perkins was a talented and gifted writer with an eye for detail. His nearly one hundred and fifty letters provided a chronicle of a story not told before: A personal account of what life was like for the individual soldier in a segregated, “Colored Battalion.” His letters described and detailed everything from life in a crowded army barracks to the particulars of what he was taught in the “separate but equal” training classes given to his battalion, the “449th Signal Construction Battalion, Army Air Corps.” Through the years readers have been presented with wonderful accounts of the “group” achievements of units like the Red Ball Express, Tuskegee Airmen, and the 761 st Tank Battalion. However, the letters I held in my hand that Saturday morning provided a look behind a curtain that had been largely closed, and tightly, since the conclusion of the war.

The journey—make that the quest—that followed to bring this story to paper took me to museums, archives, military installations, and schools across the country for the gathering of the necessary background information to fill in the gaps in Sergeant Perkins’ experiences. Along the way, the ghosts started to take form, finally started to achieve flesh and bones. It became more and more clear that the men of the 449 th , like those in so many other segregated battalions, were truly unsung, and often invisible, heroes of the great conflict of World War II.

important stories in this

area being published by

university presses? Partly

because titles written

specifically for younger

readers have not yet

found their way into

print—but they will, no

doubt, in the coming

years.

While completing this background research, I paused to take a look at the other literature written about the contributions of other African-American soldiers who served during the war. The list, at first, appeared thin. Very thin. It took side trips down many paths, but a core list of books finally began to emerge. Within this list, it immediately became apparent that most of the books about the African-American involvement in the war could be classified into four categories: Books describing specific events or battles; Unit (group) histories of the “Colored Battalions”; Books about the experiences of individual soldiers (very few. . .); Books dealing primarily with how the African- American soldiers were coping with the two-front war many were facing at the time—the conflict overseas VS the racial conflict still present on the homefront in the U.S. It should also be noted that books in these categories written specifically for younger readers are a relatively recent development, paralleling the rise of multicultural studies in the schools. For now, young readers interested in these areas will need to expand their reading horizons and sample everything from titles written specifically for them to scholarly examinations published by university presses—and everything in between (NOTE: Why are there so many important stories in this area being published by university presses? Partly because titles written specifically for younger readers have not yet found their way into print—but they will, no doubt, in the coming years.) What follows is an annotated bibliography of the core group of titles that kept showing up during my search—and those recommended to me by young readers form across the land.

An Annotated Bibliography—The African-American Experience in World War II: America’s Unsung, Invisible Heroes

Abdul-Jabbar and Anthony Walton. Brothers in Arms: The Epic Story of the 761 st Tank Battalion, WWII’s Forgotten Heroes. Broadway Publishers, 2004. (320 pages). (This story of the “Black Panthers” is a must for class libraries because of its detailed look at the almost constant racial issues that faced these gallant men while they were in combat. Young readers enjoy the third person point of view used to tell the story.)

Adler, David A. Joe Louis: America’s Fighter. Gulliver Books/Harcourt, 2005. (32 pages). (While not exclusively about Mr. Louis’ army service during WWII, the book does present a fine look at his contributions to the war effort. For primary grades.)

Allen, Robert L. The Port Chicago Mutiny. Heyday Books, 2006. (244 pages). (One of the more disturbing stories of the war. An accidental explosion killed over 300 African-American soldiers serving at Port Chicago, California. When survivors of the disaster refused to return to unsafe working conditions, over two hundred were court marshaled.)

Brooks, Philip. The Tuskegee Airmen. Compass Point Books, 2005. (48 pages). (Not as comprehensive as most books on the subject, but important because it explores the history of how the unit came about. Targeted for middle school readers.)

Bruning: John Robert, Jr. Elusive Glory: African-American Heroes of World War II. Avisson, 2001. (135 pages). (Biographical profiles of African-American soldiers who were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor (7 of them). Also includes biographical sketches of some of the more prominent Tuskegee Airmen. Targeted for middle school readers and up.)

Carroll, Peter N., Michael Nash, and Melvin Small. The Good Fight Continues: World War II Letters from the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. New York University Press, 2006 (300 pages). (A very readable account of the exploits of the “Lincoln Brigade,” a volunteer outfit that fought during the Spanish Civil War right before the U.S. involvement in WW II. Also follows the men through their eventual service with the U.S. Army and contrasts their treatment while in Spain with the discrimination they faced once they joined the American forces.)

Colley, David P. Blood for Dignity: The Story of the First Integrated Combat Unit in the U.S. Army. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2004. (240 pages). (A quick and compelling read. Relates the story of African-American troops that were added to combat units near the end of World War II. They were mostly unwelcome . . .)

Colley, David P. The Road to Victory: The Untold Story of World War II’s Red Ball Express. Warner Books, 2001 (336 pages). (One of the best accounts of the convoy unit that helped supply the troops as the allies advanced on Germany. Their contributions are described here through interviews with former drivers and detailed research. A fine book.)

Cooper, Michael L. The Double V Campaign: African Americans and World War II. Lodestar Books, 1998. (86 pages). (Describes how the contributions to the war effort were in stark contrast to the reception the soldiers received when they returned home. Has section of photos and maps. Targeted for middle school readers.)

Copeland, Jeffrey S. Inman’s War: A Soldier’s Story of Life in a Colored Battalion in WWII. Paragon House, 2006. (366 pages). (Book provides an individual, personal account of the life and service of Sergeant Inman Perkins of the 449th Signal Construction Battalion, Army Air Corps. Includes detailed Epilogue.)

Francis, Charles E. and Adolph Caso. The Tuskegee Airmen: The Men Who Changed a Nation. Branden Books, 1997 (496 pages). (Book is important because it contains over one hundred pictures, may of them never seen before, of the Airmen. The photos bring the pilots to life in a way other books do not.)

Griggs, William E. and Phillip J. Merrill. The World War II Black Regiment That Built the Alaska Military Highway: A Photographic History. University of Mississippi Press, 2002. (195 pages). (A beautiful book containing a chronological history of the creation of this important highway. Also a look at the non-combat contributions of African-American soldiers.)

Harris, Jacqueline L. The Tuskegee Airmen: Black Heroes of World War II. Dillon Press, 1996. (144 pages). (What makes this book different, and important, is that it contains many first-person accounts. Also has a comprehensive, and useful, bibliography. Targeted for middle/high school readers.)

Hasday, Judy L. The Tuskegee Airmen. Chelsea House, 2003. (108 pages). (One of the better accounts and loaded with archival pictures. Excellent timeline traces complete history of the unit. Targeted for high school readers.)

Homan, Lynn M. and Thomas Reilly. Black Knights: The Story of the Tuskegee Airmen. Pelican Publishing, 2001. (336 pages). (Another excellent book. What distinguishes this one is the authors included interviews with the pilots and their family members. A very personal, sensitive look at this exceptional unit.)

Homan, Lynn M. and Thomas Reilly. Tuskegee Airmen: American Heroes. Pelican Publishing, 2002. (85 pages). (Written in novel form, a substitute teacher keeps a class spellbound as he relates his experiences during WWII as a member of the Tuskegee Airmen. Great for a read-aloud experience. Targeted for middle school readers.)

Jefferson, Alexander and Lewis Carlson. Red Tail Captured, Red Tail Free: Memoirs of a Tuskegee Airman and POW. Fordham University Press, 2005. (133 pages). (Story is nearly unique as it is the personal account of one of the very few African- American soldiers to become a prisoner of war. Also contains the drawings done by the Airman while a prisoner in Germany.)

Kelly, Mary Pat. Proudly We Served: The Men of the USS Mason. Naval Institute Press, rev. ed. 1999. (220 pages). (Somewhat difficult to navigate at times, but still an important account of a convoy escort ship where the crew was almost entirely composed of African-American sailors. Includes letters from and photographs of the sailors.)

McGuire, Phillip. Taps for a Jim Crow Army: Letters from Black Soldiers in World War II. University Press of Kentucky, 1993. (276 pages). (Book shares a personal view of the African-American experience in WW II through letters sent home from soldiers in many of the segregated units.)

McKissack, Patricia and Fredrick McKissack. Red-Tail Angels: The Story of the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. Walker and Company, 1995. (136 pages). (One of the “Best Books for Young Adults “ in 1996. Has become something of a “modern classic” in multicultural studies. Different from most others on this subject by quality of the writing and inclusion of firstperson accounts of many of the Airmen. A must for classroom libraries.)

Moore, Brenda L. To Serve My Country, to Serve My Race: The Story of the Only African American WACS Stationed Overseas During World War II. New York University Press, 1998. (240 pages). (One of only a handful of accounts of the contributions of African-American women to the war effort. Book is based in part on interviews with those who served in the 6888 Central Postal Directory Battalion. A quick read and an important book.)

Moore, Christopher. Fighting for America: Black Soldiers—The Unsung Heroes of World War II. Presidio Press, rev.ed. 2005. (400 pages). (BIG book, but important because it includes newspaper articles of the era to supplement the text, which provides a context not found in most other books on the subject.)

Owens, Emiel W. Blood on German Snow: An African-American Artilleryman in WWII and Beyond. Texas A&M University Press, 2006. (160 pages). (Traces the life of Mr. Owens from his boyhood through his service in the war to his life after the war. One of the very few autobiographical accounts of the African-American experience during the war.)

Pfeifer, Kathryn Browne. The 761 st Tank Battalion. Twenty-First Century Books, 1994. (80 pages). (An older book, but important because it looks at the experiences of individual men who served in the battalion.)

Potter, Lou, William Miles, and Nina Rosenblum. Liberators: Fighting on Two Fronts in World War II. Harcourt, 1992. (303 pages). (Traces the birth of the 761 st Tank Battalion, from its formation to its return to the U.S. Book will also serve as an excellent supplement to the PBS special on the same subject.)

Robert, John and Jr. Bruning. Elusive Glory: African-American Heroes of World War II (Young Adult Series). Avisson Press, 2001. (135 pages). (Details the military experiences of fifteen African-American soldiers and pilots of WWII. One of these is Ben Davis, Jr., one of the original Tuskegee Airmen.)

Sasser, Charles W. Patton’s Panthers: The African-American 761 st Tank Battalion in World War II. Pocket Books, 2005. (368 pages). (What separates this account from others is the detailed look at the battalion’s help in liberating a Nazi concentration camp, an important part of the battalion’s history that has seldom been addressed in the history books.)

Stanley, Sandler. Segregated Skies. Smithsonian Paperback Series, 1998. (217 pages). (History of the 477 Bomber Group and the 332 nd Fighter Group—and how the men had to convince all around them that they were worthy of sharing the skies.)

Stillwell, Paul and Colin L. Powell. The Golden Thirteen: Recollections of the First Black Naval Officers. Naval Institute Press, 2003. (336 pages). (A wonderful oral history of the first African- Americans to become officers in the U.S. Navy. Contains interviews with eight of the original thirteen.)

Wilson, Joe and Julius W. Becton. 761 st Black Panther Tank Battalion in World War II: An Illustrated History of the First African American Armored Unit to See Combat. McFarland, rev.ed. 2006. (323 pages). (Title says it all. Beautiful and inspiring photographs of the men of the “Black Panther” unit.)

***

And two to grow on: Two titles, in particular, stand out as representing the African-American contributions in other conflicts. These are valuable as they provide young readers with important context for the books examining World War II.

Barbeau, Arthur E., Florette Henri, and Bernard C. Nalty. The Unknown Soldiers: African- American Troops in World War I. DeCapo Press, 1996. (279 pages). (One of the few, and best, accounts of the contributions of African-American troops who served in World War I. Readers may be shocked by the overt discrimination described in the book.)

Taylor, Theodore. The Flight of Jesse Leroy Brown. William Morrow, 1998. (300 pages). (Noted YA author Theodore Taylor tells the story of the first African- American U.S. Naval Pilot who flew during the Korean conflict.)

Jerome Klinkowitz, Professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa, is an editor of The Norton Anthology of American Literature, and is author of forty books of literary and cultural criticism, including studies of World War II flyers’ memoirs in Their Finest Hours (Iowa State University Press, 1989), Yanks Over Europe (University Press of Kentucky, 1996), With the Tigers Over China (University Press of Kentucky, 1999), and Pacific Skies (University Press of Mississippi, 2004).

Jeffrey Copeland is Professor of English Education and Head of the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of Northern Iowa. He has authored and edited numerous textbooks, including Speaking of Poets (NCTE) and Young Adult Literature.

William Broz is Assistant Professor of English Education at the University of Texas-Pan American. He has published several articles and book chapters on teaching writing and literature in high school, including “Hope and Irony: Annie on My Mind” which won the 2002 English Journal Hopkins Award.