ALAN v35n1 - Getting Beyond the Cuss Words: Using Marxism and Binary Opposition to Teach Ironman and The Catcher in the Rye

Getting Beyond the Cuss Words:

Using Marxism and Binary Opposition to Teach Ironman and The Catcher in the Rye

A brief return to the high school classroom in 2004 provided me with the opportunity to teach young adult literature for the first time in my career. In the six years I taught English and reading, from 1996 to 2002, I only used classic works— Great Expectations, A Separate Peace, Romeo and Juliet, etc. It wasn’t that I didn’t like or want to teach young adult fiction; my schools never provided such titles. Don’t get me wrong. It is not that I dislike the canon either. Certainly, there are titles and authors I hope all students have the opportunity to read: To Kill a Mockingbird for its social justice theme, Faulkner for his use of the Southern grotesque, and The Scarlet Letter for its timelessness. However, most of the classic titles we read were not interesting to, or at the appropriate reading level for, my remedial and average level students, most of whom were at risk of failing. At one point, frustrated with the lack of relevant literature for my students of color, I purchased titles I hoped they might like: Black Like Me and A Raisin in the Sun. The students were excited, and we dived into them, moving beyond a great story to analyzing themes, symbols, and characters. Relating to the works and the characters, the students moved beyond their labels (remedial and/or average) and became honors students. Seeing the increased confidence, competence, and attitude among my students, I borrowed books from the Advanced Placement program— Bless Me, Ultima and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings —and we continued reading. It was this experience that taught me the most about labels and expectations. Perhaps I, too, had been guilty of shortchanging my students.

Never forgetting this lesson, I revamped two of my courses (Teaching Fiction and Adolescent Literature), choosing to pair young adult with classic literature and incorporate literary theory. One project requires students to (1) thematically pair a recently published, award-winning young adult novel with a commonly taught classic work (novel or drama) and use them to (2) create lessons to teach literary theory. Moreover, their lessons need to focus on regular or remedial students in grades eight through ten.

classes are often rel-

egated to a narrow range

of literature.

Pairing of novels by theme and using literary theory are integral for two main reasons. First, my experience as a high school teacher showed that upper track students, like those in honors and Advanced Placement classes, receive more in-depth instruction with an emphasis on critical thinking skills (see also, Applebee, 1989 , 1993 ; Finley, 1984 ; author, 2004 ). Moreover, these students read a wider range of literary works, whereas students in lower track classes are often relegated to a narrow range of literature. Second, as stated earlier, I was never provided with young adult novels to use with my students, novels which would have interested them and, perhaps, prompted them to participate more in class. I had either nothing or the abridged versions of classic works (A Separate Peace, Great Expectations, etc.) included in the anthology which were at least two grades above most students’ reading level.

Both of these factors—readings with little relevance to students’ lives and literature too difficult for them to read—contribute to low interest and achievement levels and provide a justification for using young adult literature even if an exact definition for young adult literature may be elusive. Herz and Gallo ( 2005 ) note that there is “no agreed-upon literal definition of YAL [young adult literature]. Others have defined it as any kind of literature read voluntarily by teenagers, while some describe it as books with teenage protagonists, or books written for a teenage audience” (11). Young adult literature serves two primary purposes: It gets students interested in reading and allows teachers to provide challenging assignments. The latter purpose is where literary theory comes in. Young adult literature, according to Ted Hipple, “must be read with attention, not simply to its story lines, characters, or settings but also and very importantly to its themes” ( 2000, 2). Lisa Schade Eckert ( 2006 ) adds to the discussion, asserting that:

Teaching students to use literary theory as a strategy to construct meaning is teaching reading. Learning theory gives them a purpose in approaching a reading task, helps them to make and test predictions as they read, and provides a framework for student response and awareness of their stance in approaching a text... making literary theory an explicit part of instruction provides a teacher with opportunities to model ways of reading instead of merely translating a text (8).

In this article we attempt to illustrate these opportunities as we present aspects of one university student’s (Candace) project, the pairing of two controversial novels— Ironman and The Catcher in the Rye —aimed at ninth- or tenth-grade students. Along the way, we hope to provide access to literary theory for teachers who may not have background knowledge in it and how to make it relevant for students. We also hope to illustrate purposes of pairing a young adult novel with a classic literary work, such as showing students that classics still have relevance in their lives and that young adult fiction has significance beyond interesting plots and characters. First, we offer a rationale for pairing of Ironman and The Catcher in the Rye, brief summaries of the novels, and theme and theory connectors. Then, short introductions to applicable literary theories are given to provide teachers with a starting point. Lastly, we present one idea in practice. Other young adult and classic literature pairing ideas are provided as an appendix.

Rationale for Pairing Ironman and The Catcher in the Rye

Many literacy experts advocate pairing young adult literature with classic works. In the edited series Adolescent Literature as a Complement to the Classics ( 1993, 1994, 1997, 2000 ), Joan Kaywell’s contributors offer dozens and dozens of pairings of young adult novels and classic works with teaching ideas. Herz and Gallo’s ( 1996 ) text, From Hinton to Hamlet: Building Bridges between Young Adult Literature and the Classics, offers pairings, thematic connections, and archetypes in the works. Their updated and revised edition ( 2005 ) has additional features including an example of an author paper and profiles of unique programs in libraries and schools. All texts make the same claim: Young adult literature, because of its focus on polemical and present-day problems and issues meaningful to adolescents, is a natural scaffold to the classics ( Probst, 2004 ). By reading modern-day, relevant works they enjoy, adolescents will more likely read and understand the classic titles assigned in school.

Students in my fiction course were directed to read a recently published young adult novel and select a commonly taught classic work with which to pair it thematically. Out of the eight titles offered (Ironman, Whale Talk, Postcards from No Man’s Land, Inventing Elliot, A Northern Light, The House of the Scorpion, Mississippi Trial, 1955, and Crossing Jordan), Candace chose Ironman and then paired it with The Catcher in the Rye. Ironman, by Chris Crutcher, is an excellent selection to use as a bridge to a classic text because it deals with several critical issues facing today’s students, such as anger management, divorce, and moving beyond initial assumptions (race, sexual preference, etc.). Salinger’s novel, The Catcher in the Rye, pairs well because of the numerous thematic parallels that exist between the two works. The protagonists, Beau and Holden, experience some of the same personal struggles and discoveries. Both authors employ writing styles that are personal and easily accessible to high school students. Both novels would work well in the high school classroom, as Crutcher and Salinger have a gift for tapping into the teenage experience through language and characterization.

Plot Summaries

Ironman by Chris Crutcher

Beauregard (Beau) Brewster appears to be your typical high school senior, making average grades, playing on the football team, and working at an afterschool job. Two things, however, set Beau apart from most of his peers: his difficulty controlling his temper and his determination to compete in Yukon Jack’s Eastern Invitational Scabland Triathlon. Through a series of letters to Larry King, Beau unravels the story of his senior year. He quits the football team, setting up a series of negative interactions with both his former coach and his father. He then is sentenced to three months of anger management classes, in lieu of suspension, for calling one of his teachers (the ex-football coach) an obscene name. Through this experience and the relationships formed with other group members, Beau begins to understand where his anger comes from and how to control it. He also starts to see some of the problems his peers face. As he gains this valuable experience, it helps him cope with some of the problems in his life. He attempts to address the volatile relationship with his father and learns the critical lesson of acceptance. All the while, Beau is training for competing in Yukon Jack’s Ironman competition. In the end, Beau accomplishes his physical goals and is working toward repairing the relationship with his father. The reader ends the book with a more mature, responsible Beau.

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

From the outset, Holden Caulfield is not your typical high school junior, failing out of four preparatory schools because of what he calls their high levels of “phoniness.” Holden begins his tale from an undisclosed mental institution in California, the narrative taking the reader through a series of events happening between the end of fall term and the start of winter break. Expelled yet again, and not wanting to inform his parents, Holden decides to leave school early and stay in a hotel until he is due home. In the city, Holden encounters and interacts with several diverse people: nuns, a hotel doorman, a prostitute, and a few acquaintances. Because of his peculiar behavior, none of the encounters seem to turn out right, and he is constantly disappointed by the “phonies,” “bastards,” and “pains in the ass.”

Holden is a teenager searching for purpose in life. The only times he appears happy are when he is with children or remembering his dead brother. Holden’s tale ends as he decides not to run away from home after all. The reader does not learn how he ended up in a mental institution, only that he will try harder in school.

Themes and Theory Connectors

Candace chose the five themes listed below to focus on when creating her unit, believing that students would be interested in and identify with the stories and characters through them. For example, high school is a time when adolescents search to find their individual identities, balancing physical maturation and emotional self-control.

- Search for identity

- Maturation

- Confrontation of the cultural other

- Self-control

- Truth versus deception/ Perception versus reality

Although the teen protagonists in Ironman and The Catcher in the Rye are strikingly different (Beau is a goal-oriented athlete, while Holden is a chainsmoking failure), their personal quests are the same. Both Beauregard Brewster and Holden Caulfield are on a journey, with each striving to develop a sense of himself and the world around him. During their journeys, the young men confront various situations that contribute to their developing sense of self. Crutcher and Salinger establish similar contrasts in the worlds of their protagonists. Beau must learn to control his anger through distinguishing truth from deception, while Holden must learn to take responsibility for his actions by denying the fictions he creates in face of the reality in which he lives. The cultural other is represented in both texts through the presence of homosexuality. Beau must cope with his role model’s admitted homosexuality; although Holden never receives confirmation of his suspicions, he thinks that one of his former teachers may be gay. Both texts leave the reader with a sense that both young men are on the road to adulthood.

Literary Theories

Two literary theories—Marxism and binary opposition—work well with the paired novels. As lack of power of his world is one of Beau’s major struggles, Marxist theory is a natural choice to introduce Ironman (and then use with Catcher ). Binary opposition also applies, especially when using Ironman as the bridge to Salinger’s book, due to the paired concepts such as right/wrong, adult/child, gay/straight, and ambivalence/certainty. Table 1 highlights how Marxism and binary opposition relate to the two novels. Other literary theories also work quite well with these two novels, and these are provided in Table 2.

| Novel | Marxism | Binary Opposition |

|---|---|---|

| Ironman | A power struggle is represented by the conflict between the people in power, composed of teachers, parents, college students, and the adolescents. The adolescents struggle to find their voices in a world that often discounts their viewpoints. |

There are many examples of binary opposites in the text: the presence of Beau, an athlete, in the anger management group with the delinquent students, Beau’s parents, the concepts of winners and quitters, Elvis’s and Beau’s family situations, anger and self-control.

|

| The Catcher in the Rye | A class struggle is represented in Holden’s plight to avoid becoming one of the phonies he so adamantly opposes. Holden’s privileged status is in stark contrast to the scenes and people he encounters in New York. | There are many examples of binary opposites in the text: success and failure, direction and misdirection, affluence and poverty, innocence and experience, reality and deception. All of these opposites are expressed in Holden’s experiences and observations. |

Marxist Theory

Marxist theory is accessible for teachers, even without having background knowledge on Karl Marx. Through Marxist theory students can investigate (1) how people are treated differently in texts (as in class systems), (2) the political context of texts, (3) how texts and their readers are socially constructed, and/or (4) the form of texts ( Appleman, 2000 ; Moon, 1999 ). Through this theory students can examine issues of power, class, resistance, and/or ideology. Literary Terms by Moon and Critical Encounters in High School English by Appleman provide ideas and activities for teachers to use. One exercise in particular works nicely with the novels. Teachers have students list social groups that are presented in each novel; then, they plot the groups on a social ladder, explaining the power struggles between and among them ( Appleman, 2000, 164-165).

In creating a pre-reading lesson for Ironman, Candace combined ideas presented in the Appleman and Moon texts. To introduce Marxism, the teacher asks students to think about class and power structures, through the cliques and groups, at their school. Using the examples of jocks and nerds, students volunteer examples of some of these groups, listing them on the board. Students then rank the groups from most to least powerful, providing justification for their responses. Some key questions teachers could pose include: Are there specific groups with power? Without power? Where does the power come from in these groups? Is your perception of power affected by your personal experiences with some of these groups? Are class structures fixed or is it possible to move among the class designations (think of the American myth of rags to riches or the cycle of poverty)? She/he will then explain that power and class structures are a part of a literary theory called Marxism and that the novels they will be reading include issues of power between and among characters and groups.

Binary Opposition

Binary oppositions are words and concepts that a community generally deem as being opposed to each other. People often have a black and white view of the world which can impact the way power is distributed among groups ( Moon, 1999 ). In studying binary opposites in a text, one does not necessarily have to look for direct opposites. Students can be led to examine how characters, actions, words, and events are positioned to be seen as contradictory.

Teachers can introduce the concept by writing pairs of opposites (such as rich/poor, liberal/conservative, or intelligent/unintelligent) on the board and asking students to make observations about the pairs. To shift the discussion to how an author crafts language, the teacher could place students in pairs and begin a discussion of word choice. For example, she/he places an example sentence on the board and asks the class how word choice might change the meaning of the sentence (examples: “the boy ran” versus “the boy fled;” “the winning team slaughtered their opponent” versus “the team squeaked by with a win”). Students could then create 2-3 sentence pairs where word choice impacts the meaning, then share and discuss the implications and interpretations.

Through studying binary opposition, students gain a better understanding of how an author’s choices create meaning within a text. Students are introduced to the idea that an opposite can be implied, rather than directly stated. Hopefully, they will become more observant readers, noticing and appreciating the deliberate choices and juxtapositions that authors choose. Key questions related to Ironman and The Catcher in the Rye that could be posed are:

- Why are binary opposites important in this/these novels? Think about opposing forces (such as real versus phony) and characters (such as Beau’s father and Mr. S).

- Are all the binary opposites presented in the texts direct opposites? Why do we consider certain pairs opposites?

- How do binary opposites work together to create meaning? How does Salinger use opposites to create Holden’s character? Consider the idea of a negative definition.

- Can a binary opposite be implied in a text? In the texts are there any areas where an opposite is implied?

- Why is word choice important? Find an example in one or both of the novels.

- How does word choice affect the tone and purpose of a piece? Use examples from the text to explain your answer.

- Consider the characters of Mr. Redmond and Mr. Serbousek. Can characters function as binary opposites? What about Mr. Nak?

- Think about the language used in Ironman and The Catcher in the Rye. Is the “foul” language necessary? Do you think the choices made by the authors were deliberate? Are they accurate, offensive, excessive, understated?

Idea in Practice

POWER AND CLASS IN SOCIETY AND BOOKS

Step One

Think about the following public figures or groups and the power they have. Where does it come from? Why are they considered powerful? Who is the most powerful? In small groups, rank the people from most to least powerful. Take 10-15 minutes. Be prepared to share your answers with the class.

George W. Bush

Paris Hilton

Oprah Winfrey

Bill Gates

Fox News

Step Two

Now, think about power at your school. In your groups, think about different groups here at _________ High School, such as “jocks” or “teachers” or “nerds.” How is the power spread among groups at school?

On a sheet of chart paper, list the groups here at school from most to least powerful. How did you arrive at this ordering? Are you a member of any of these groups?

Now, reconsider (and renumber if necessary) your list from the perspective of:

—the least powerful on your list

—teachers

To test and practice some of the ideas presented in this article, an English teacher at a local high school agreed to let me come into her 10 th grade class (31 students) and teach the introductory lesson for the novel Ironman. I combined the ideas of Moon, Appleman, and Candace in a two-part lesson. This pre-reading lesson works well because students begin to study how power is assumed, granted, and shown in their day-to-day worlds before they read about it in either of the novels. Because Ironman opens with Beau’s power and control issues, the class discussion will be fresh in students’ minds. Students were given a copy of the handout shown in Figure 1 and instructed to complete Step One.

My initial assumption was that students would select George W. Bush as the person/group with the most power. However, the student groups were split, with some choosing him and others choosing Fox News and Bill Gates. For those groups that chose the President of the United States, the reason was that the U.S. is the most powerful country on earth; thus, its leader is the most powerful of the names listed. Those who chose Fox News justified their choice with comments relating to the news channels being able to manipulate information. Bill Gates was seen as powerful because of his wealth and control over a large section of the technology market.

of school social hierarchy.

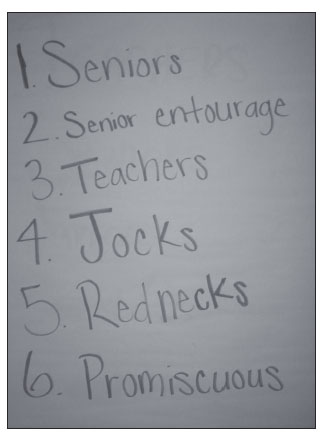

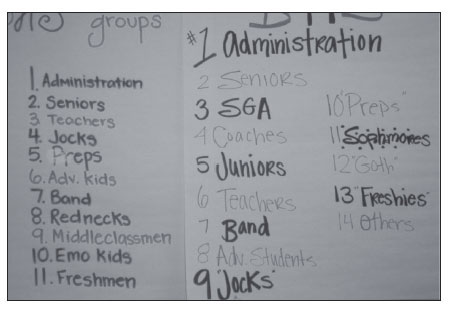

I segued into the second part of the lesson by stating that just like there is disagreement over which public figures are most powerful, the same situation occurs in schools. Some people and groups, such as administrators and coaches, have power (or should) automatically due to age, title, and/or size. However, from school to school, that is not always the case. I went over the directions in Step Two, providing each group with markers and poster-size paper. The photographs in Figures 2 and 3 represent three groups’ interpretations of the power hierarchy in their school.

What is interesting, and became even more so for the students and their teacher and I during the discussion (which lasted so long that we did not finish the lesson), is not only the difference in the number of power groupings that each student group identified, but some of the particular ones acknowledged as having power. For example, in Figure 2, students indicated that the “Promiscuous” group, though ranked last on their list, exerted influence because their sexual activity made them popular and powerful. Those expected to have power—administrators—were left off the list, and teachers were not listed at the top.

social hierarchy.

Two additional groups interpreted the school’s power players differently, listing a wider variety and number of them (see Figure 3). While both saw administrators as having the most power, teachers were listed behind those in the senior class (and in one case, after student government members, coaches, and juniors). Students also noted power being held by some atypical groups, namely “emo kids.” In fact, neither the teacher nor I knew what an emo kid was and had to ask the class. According to the students, emo kids are the ones who either display mood swings and/or emotional outbursts or cut themselves. Although this group displays unhealthy behavior, its members are still power brokers over some in the school because of the attention they seek and receive from others. The discussion that ensued from this activity was beneficial not only as an introduction to the themes in the novels, but to open awareness and tolerance among the class.

Summary

What the teachers in my class and I learned is that pairing young adult and classic fiction and incorporating literary theory multiplies the benefits of both. First, young adult literature is a great hook to get students interested in and reading classic works. Because they are given a foundation of ideas, themes, and issues, the scaffold is in place for the more difficult reading. Second, when teachers use literary theory, students—especially those in the lower academic tracks—are provided with higher-order and critical thinking opportunities that they might not receive. While I am an advocate for reading young adult literature for its own sake, I do not endorse reading it without integrating more complex, in-depth assignments and activities, a requirement that literary theory fulfills.

Works Cited

Applebee, Arthur J. A Study of Book-Length Works Taught in High School English Courses (Report Series 1.2). Albany, NY: Center for the Learning and Teaching of Literature, 1989.

Applebee, Arthur J. Literature in the Secondary School: Studies of Curriculum and Instruction in the United States. NCTE Research Report No. 25. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 1993.

Appleman, Deborah. Critical Encounters in High School English: Teaching Literary Theory to Adolescents. New York and Urbana, IL: Teachers College Press and National Council of Teachers of English, 2000.

Eckert, Lisa S. How Does it Mean? Engaging Reluctant Readers through Literary Theory. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2006.

Finley, Merilee K. “Teachers and Tracking in a Comprehensive High School.” Sociology of Education, 57(1984): 233–243.

Hipple, Ted. “With Themes for All: The Universality of the Young Adult Novel.” In V. R. Monseau & G M. Salvner (Eds.), Reading Their World: The Young Adult Novel in the Classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2000. 1–14.

Herz, Sarah K., & Gallo, Donald R. From Hinton to Hamlet: Building Bridges between Young Adult Literature and the Classics. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Herz, Sarah K., & Gallo, Donald R. From Hinton to Hamlet: Building Bridges Between Young Adult Literature and the Classics (2nd ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2005.

Kaywell, Joan F. (Ed.). Adolescent Literature as a Complement to the Classics (Vols. 1–4). Norwood, CT: Christopher Gordon Publishers, 1993-2000.

Moon, Brian. Literary Terms: A Practical Glossary. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 1999.

Probst, Robert E. Response and Analysis: Teaching Literature in Secondary School (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2004.

Scherff, Lisa. “I Wish We Read Better Books.” What High School Students Reported about Required Reading. The Leaflet, 103 (2004): 9–20.

Bibliography (classic text listings include recent edition information)

Cather, Willa. My Antonia. New York: Pocket Books, 2004.

Chambers, Aidan. Postcards from No Man’s Land. New York: Puffin, 2004.

Chopin, Kate. The Awakening. New York: Avon, 1982.

Cormier, Robert. The Chocolate War. New York: Random House, 2000.

Crowe, Chris. Mississippi Trial, 1955. New York: Puffin, 2003.

Crutcher, Chris. Ironman. New York: Harper Teen, 2004.

Crutcher, Chris. Whale Talk. New York: Laurel Leaf, 2002.

Donnelly, Jennifer. A Northern Light. Orlando: Harcourt, 2003.

Farmer, Nancy. The House of the Scorpion. New York: Simon Pulse, 2002.

Fogelin, Adrian. Crossing Jordan. Atlanta, GA: Peachtree Jr., 2002.

Gardner, Graham. Inventing Elliot. New York: Dial, 2004.

Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World. New York: Harper Perennial, 1998.

Lee, Harper. To Kill a Mockingbird. New York: Harper Perennial, 2002.

Salinger, J. D. The Catcher in the Rye. New York: Little, Brown and Co., 1991.

Shakespeare, William. Othello. New York: Dover Publications, 1996.

Taylor, Mildred D. Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. New York: Puffin, 1991.

Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. New York: Penguin Classics, 2003.

Appendix

|

Reader

Response |

Formalism | Feminism | Race |

Cultural

Studies |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ironman |

|

|

|

|

|

| The Catcher in the Rye |

|

|

|

|

|

| Young Adult Novel | Classic Work |

Primary Literary

Theories |

Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Northern Light | My Antonia |

Feminist

Race |

Donnelly’s A Northern Light and Cather’s My Antonia share many features in terms of plot and theme. The pairing works well for these reasons alone, but also in light of the critical approaches of feminism and race theory. Because students can sometimes be resistant to the use of literary theory, teachers can introduce the unit with A Northern Light, a young adult text that is full of exciting events including a murder and the pursuit of a college education. This is a great strategy to create student interest for the more traditionally accepted My Antonia, which explores similar themes of farm life, death, and college education. After becoming familiar with the novels by exploring the connections of plot and theme, students will be better prepared to examine the texts through the literary lenses of feminism and race theory. |

| A Northern Light | The Awakening |

Feminist

Marxist |

A Northern Light is an ideal piece of literature to teach with The Awakening because the themes and subject matter appeal to students, particularly females. Some themes covered include love, familial duty, feminine stereotypes, race, educational aspirations, and loss. Concerning roles and stereotypes of women in early 20 th century, both female protagonists Mattie Gokey and Edna Pontellier strive to achieve beyond their supposed place in society. Readers can examine the ways that education is a commodity only openly distributed to certain populations (men). As a woman, Mattie is already disadvantaged because she is supposed to rely on men for many things. Edna is similar to Mattie in that, as a woman, she is seen as under the control of a male, Mr. Pontellier. |

| Crossing Jordan | Othello |

Race

Structuralism (binary opposition) |

In Crossing Jordan, race is the line that divides the families, although the divide is not caused by current human interaction, but historical racial differences and past personal experiences. In Othello, differences in color and class are central characteristics of the play. By studying these texts through the Race Theory Lens, students can observe how misguided intolerance causes a disconnect in humanity that divides for the sake of division. The second lens of literary analysis is Binary Opposition. By analyzing the figurative and literal lines in these stories, students will gain a deeper and more educated point of view in the study of these texts. They will see how the authors used this critical theory method to heighten the impact of separateness and compartmentalization within the whole of the texts. |

| Whale Talk |

The Adventures of

Huckleberry Finn |

Race | One of the most pertinent theories applicable to both novels is race theory. Both novels deal heavily with the issue: Huck Finn revolves around Huck’s adventures and friendship with a runaway slave, and his battle between his conscience which states he must turn Jim in as a runaway, and his heart which tells him that Jim is human, and thus deserves freedom. Whale Talk deals with the expectations and stereotypes facing blacks today (good athletes, not that bright), and the hurt dealt to children by prejudice. |

| Mississippi Trial, 1955 | To Kill a Mockingbird |

Race

Feminist Marxist |

Mississippi Trial, 1955 and To Kill a Mockingbird both have the obvious racial issues, both with a trial that comes to an unjust verdict because of the racist jury members who feel a sense of pressure from their community members. The novels are both set in the deep rural South during the time of Jim Crow Laws that enabled whites to have a sense of power and entitlement over blacks. Feminism can be used in Mockingbird to discuss the role of Scout and how she is expected to be something that she does not feel. In Mississippi Trial, 1955 there are very few women. Can looking through a feminist lens help the reader understand why that the novel was written in that way? Is the story more effectively told with only three female characters, all of who play very small roles? Marxism can be used to look at the classes of the characters: Would the stories be different if the white families were of lower or higher classes than they are? Would there be a story at all? |

| The House of the Scorpion | Brave New World |

Race

Feminist |

An excellent companion book to Brave New World is The House of the Scorpion which addresses contemporary issues such as drug cartels and cloning. Students will easily relate to the story’s protagonist who must cope with thoughts that he is somehow different from everybody else. The main characters in Scorpion are Latino, a welcome change for minority students used to the traditional Anglo texts often found in their anthologies. Racism is shown through Huxley’s social slave system and Farmer’s clones. The women in Brave New World become the protagonists in sexual exploration while in Scorpion they are positioned in traditional roles, despite their strengths or weaknesses. |

| Crossing Jordan |

Roll of Thunder, Hear

My Cry* |

Race | A great way to teach students about boundaries using race theory is through Crossing Jordan and Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. Although the books are set in different times, one in the early 1900s and the other in the late 1900s, students are able to see how racial boundaries that were set have either changed or have remained unchanged. Students will be able to make personal connections between the books and their lives. Through this lesson, they will be able to understand how to begin to break down barriers that occur in their lives. |

| Inventing Elliot | Chocolate War* |

Reader-Response

Structuralism |

Inventing Elliot serves as a great accompaniment to The Chocolate War. The novel portrays similar themes without any controversial language or content. The novels will reach out to most students and generate some type of reaction that will cause students to compare the text to their own lives. Reader-response theory can help students who are bullies try to relate to the experiences of victims, such as those found in both novels. Structuralism as a binary opposition works well with Inventing Elliot. In the opening, Elliot reveals his desire to leave his old life behind and to create a new life. Even though Jerry’s life (The Chocolate War) is somewhat of a binary opposition because he alters from a sheer determination to “disturb the universe” to a panicked willingness to submit, this example is not quite as obvious as Elliot’s two sides. |

|

* Although considered young adult literature, because they were originally published in the 1970s, students considered them to be “classics.”

Note 1. Additional pairings contributed by Zachary Best, Carmen Brown, Misty Daniels, Scott E. Jenkinson, Laura Keigan, Sarah McAffry, Beth Nelson, Elaina Robertson, Sherri Teske, and Hazel Tucker |

|||

Lisa Scherff is assistant professor of English Education at The University of Alabama, where she also co-directs the Longleaf Writing Project. Lisa and Susan Groenke (University of Tennessee, Knoxville) were recently named co-editors of English Leadership Quarterly.

Candace Lewis Wright lives and works in Knoxville, Tennessee. She has a Bachelor of Arts degree in English and a master’s degree in secondary education from the University of Tennessee. She enjoys reading and watching HBO’s The Sopranos with her husband Mike.