“More than Meets the Eye”:

Transformative Intertextuality in Gene Luen Yang’s

American Born Chinese

Early in Gene Luen Yang’s young-adult graphic novel American Born Chinese , the protagonist, Jin, responds to an elderly woman’s question about what he wants to be when he grows up by saying that he wants to be a “Transformer.” Since he has one of the eponymous toys with him, he shows her how it can change from a truck to a robot, becoming “more than meets the eye” (28). The older woman, the wife of the Chinese herbalist Jin’s mother is seeing, isn’t impressed. She replies that “It’s easy to become anything you wish . . . so long as you’re willing to forfeit your soul” (29).

While we might recognize this exchange as an allusion to the Faust story, Yang has that in mind and more. Through three parallel storylines, Yang weaves together a complex tale of transformation through three characters: the legendary Chinese Monkey King; an apparently white boy named “Danny,” who annually faces the shame of his visiting cousin, the grotesque Chin-Kee; and Jin himself. All three characters make reckless deals to gain access to previously impenetrable spaces, though the “devil” each bargains with is himself. In its complex intertextuality, Yang’s graphic novel poses challenging interpretive tasks for its young readers, and ultimately forces them to confront their own complicity in the racist stereotypes prevalent in some of the intertexts.

By virtue of its very form, Yang’s graphic novel is intertextual, as it alternates between these three stories, telling first the tale of the Monkey King, then Jin’s story, then Danny’s story, which is framed as a bad TV sitcom, complete with canned laughter. Only at the end do they come together, though there are clear connections between the stories throughout. In the process, it calls upon its young readers to make sense of the three seemingly disparate storylines, as well as numerous additional texts referenced along the way: Faust, as mentioned above, the classic 16th-century Chinese novel Journey to the West , and the Bible, as well as nontraditional “texts,” such as superhero comics and manga, children’s folklore, TV shows, toys, and YouTube. In the ways it combines and conflates traditional and nontraditional allusions in its intertextuality, Yang’s novel levels the playing field between “high” and “low” art, “canonical” and “popular” literature, thus enabling young readers to feel a sense of authority about their interpretive skills.

The Nature of Interextuality

Though the general idea of texts “speaking” to and through each other existed long before the term “intertextuality” was coined by Julia Kristeva in her 1980 work Desire in Language , Kristeva complicates the notion by positing that the relationships between texts occupy only one “axis” of interpretation; the reader and the text itself occupy another, intersecting axis. The resulting intersections suggest that texts only have meaning in relation to each other and in relation to each reader and each reading. As Roland Barthes argues, “A text is . . . a multidimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text is a tissue of quotations. . . . The writer can only imitate a gesture that is always anterior, never original. His only power is to mix writings, to counter the ones with the others, in such a way as never to rest on any one of them” (Barthes 146).

Of course, intertextuality can be visual as well as textual. Comics writer and theorist Scott McCloud reinterprets the idea of intertextuality for the art of comics by focusing on the ways in which reading comics requires the reader to fill in and interpret not only the images in panels themselves, but more important, in the spaces between panels. For McCloud, that “blank ribbon of paper” (88) between panels

asks us to join in a silent dance of the seen and the unseen . The visible and the invisible . This dance is unique to comics. No other artform gives so much to its audience while asking so much from them as well. This is why I think it’s a mistake to see comics as a mere hybrid of the graphic arts and prose fiction. What happens between these panels is a kind of magic only comics can create. (92, emphasis McCloud’s)

McCloud’s argument here suggests that reading “sequential art” may be the earliest form of intertextuality that young readers encounter, in the ways it asks them to make links not only between word and image on a page, but to make meaning—literally—in the margins between panels.

While the commonplace rationale for using graphic novels in the English/language arts classroom is that they appeal to visual learners, McCloud’s work implies that they may hold the power to appeal to aural and kinesthetic learners as well. Even though “comics is a mono-sensory medium [that] relies on only one of the senses [sight] to convey a world of experience,” McCloud argues that the reliance on the visual in the panels themselves forces readers to use their other senses—sound, touch, taste, and smell—in between panels to create the context for the visual (89). McCloud suggests that this means that

Several times on every page the reader is released—like a trapeze artist—into the open air of imagination . . . then caught by the outstretched arms of the ever-present next panel! Caught quickly so as not to let the readers fall into confusion or boredom. But is it possible that closure can be so managed in some cases—that the reader might learn to fly? (90)

Gene Luen Yang himself echoes this idea in his master’s thesis, in which he argues that “comics can serve as an intermediate step to difficult disciplines and concepts” (Yang, “Strengths”). As such, graphic novels have transformative potential to aid multiple kinds of learners to understand and become skillful at the complex tasks of literary interpretation. And Yang’s own American Born Chinese , in particular, offers some very concrete and—for young readers immersed in popular culture—very recognizable ways to understand intertextuality, and to see how they can be active participants in making meaning in a text.

As teachers, we’re well aware of students’ need to understand intertextuality—to be familiar enough with “classic” texts that they can appreciate the ways references to them reappear in other texts, allowing them to understand, for instance, the humor of the unintentional misquotations of Hamlet’s Soliloquy and the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn , or to see how Jane Austen’s Emma was adapted to make the film Clueless . Such familiarity with traditional texts can even enhance students’ viewing of pop-culture productions that refer to them, such as The Simpsons revision of Poe’s “The Raven” in one of their seasonal “Treehouse of Horror” episodes. 1 Teachers recognize that this skill can create a powerful sense of mastery in students, which may, in turn, make them more eager readers of more complicated texts.

American Born Chinese , then, gives us a literal illustration of one way comics can provide a kind of “intermediate step to [the] difficult . . . concept” of intertextuality. Specifically, Yang’s graphic novel achieves this by using intertextuality in both traditional and innovative ways. As mentioned above, the novel includes references, both textual and visual, to mythological and Biblical narratives—precisely the kinds of intertexts we hope students will learn to recognize in other texts. However, in my experience teaching American Born Chinese , those are the allusions students are least likely to recognize and use as tools in their interpretation of the text. Instead, Yang’s clever use of non traditional intertexts emerges as the single feature of the novel that students most seem to latch on to and appreciate. Students’ experience of “getting” these references introduces them to the thrill that intertextuality can bring, and to the ways in which one’s understanding of the previously known text can help one interpret the new and less familiar text. And in a larger sense, developing the skill of using the familiar to make sense of the strange is echoed in American Born Chinese ’s primary theme: that of the need to recognize racial stereotypes before being able to dismantle them.

I taught this text to a group of preservice teachers in a recent young adult literature (YAL) course; their responses to it, I think, illustrate the ways American Born Chinese challenges even relatively sophisticated, college-aged readers. This, in turn, suggests that using Yang’s graphic novel in the secondary classroom might help students recognize the strengths and weaknesses in their own interpretive abilities and help them make the important jump from being able to recognize and interpret popular-culture allusions in texts to recognizing and interpreting more traditional kinds of allusions. In many ways, in fact, Yang’s novel calls on its readers to look more critically at the seemingly trivial references that make up their understanding of Asian American cultures, and in so doing, to see how participating in their transmission may make them complicit in the process of ethnic stereotyping.

Types of Intertexts in American Born Chinese

Broadly speaking, both the classical and contemporary intertexts in Yang’s novel tend to fall into three groups: those that are empowering; those that are disempowering or racist; and those that fall in the large, ambiguous space between the two.

Among the empowering intertexts the novel draws on are the Monkey King legend (on the classical side) and “Transformer” toys and superhero comics (on the pop culture side). We are introduced to these intertexts in the interstices between the text’s first storyline, that of the Monkey King, and its second, that of Jin’s childhood. The first installment of each storyline shows the “hero” having his first experience with racism and internalizing it: The Monkey King is turned away from a dinner party in Heaven because he’s a monkey and doesn’t wear shoes; when he returns to his kingdom, he notices for the first time the overwhelming smell of monkey fur in his chamber (20). He institutes a new rule that his fellow monkeys must start wearing shoes and then trains himself in the “four disciplines of invulnerability” to cold, fire, drowning, and wounds; he also masters the abilities to shape-shift, turn himself into a giant, and perform other amazing feats. He uses these abilities to wage war on the Ao-Kuang, Dragon King of the Eastern Sea; Lao-Tzu, Patron of Immortality; Yama, the Caretaker of the Underworld; and the Jade Emperor, Ruler of the Celestials, finally declaring himself “The Great Sage, Equal of Heaven.” While the epic comic-book battles waged by the Monkey King suggest his physical superiority, it is clear that what he is fighting is his own monkey nature.

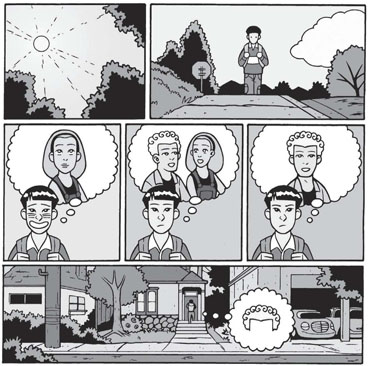

Similarly, in the second storyline, Jin’s parents move from Chinatown to the suburbs, where Jin for the first time sees himself as others see him: Jin’s third-grade teacher tells the class that he’s just moved there from China (“San Francisco,” Jin corrects), and tells a boy who says that “Chinese people eat dogs” that she’s sure that “Jin’s family probably stopped doing that sort of thing as soon as they came to the United States” (30–31). Like the Monkey King, Jin suddenly notices the smell of his own fur, metaphorically speaking, and starts working to separate himself from it; he and the “only other Asian in [the] class . . . Suzy Nakamura . . . avoid each other as much as possible” (31), and when another student, Wei-Chen, arrives from Taiwan, Jin notes that “Something made me want to beat him up” (36). However, while he studiously tries to avoid Wei-Chen, eventually they realize they only have each other, and Wei-Chen’s Transformer—a monkey/robot figure—opens the door to their ambivalent friendship. Though the Transformer is just a toy in this sequence, its metaphorical significance has already been explained in Jin’s encounter with the herbalist’s wife. Only later will Jin understand the empowering nature of the Transformer, as we will see.

The disempowering intertexts function as a crucial connection between Jin’s narrative and the third storyline, that of the seemingly white boy named “Danny.” Here, the intertexts are largely from the realms of popular culture and folklore. Eventually, these storylines also reference the more empowering intertexts mentioned before, but for much of the novel, the disempowering intertexts dominate, and thus merit a closer look.

Most crucially, Danny’s entire story is framed as a bad sitcom titled “Everyone Ruvs Chin-Kee,” a device that both normalizes its representations and calls them into question. At the outset of Danny’s story, Danny is on the verge of asking his beautiful blond classmate Melanie for a date when his mother announces the arrival of his cousin Chin-Kee for his annual visit from China. Chin-Kee is, literally, an outsized Chinese stereotype, with his buck teeth, pigtail, fawning mannerisms, and ludicrous dialect. Chin-Kee is straight out of central casting for a bad 1920s “Yellow Peril” film, and his cartoonishness makes him both scary and ludicrous. Melanie is terrified by him, thus ending Danny’s chances with her, even though he insists that he’s “nothing like him! I don’t even know how we’re related!” (123). Later we learn that Danny has switched schools every year because of Chin-Kee’s disruptive visits, which always seem to occur just as Danny has “made some friends, gotten a handle on [his] schoolwork, even started talking to some of the ladies” (126). As Danny says, by the time Chin-Kee leaves, “[N]o one thinks of me as Danny anymore. I’m Chin-Kee’s cousin” (127).

Mirroring Danny’s isolation and shame, Jin, Suzy, and Wei-Chen take out their internalized racism on each other in increasingly hurtful ways, even as they are collectively denigrated by racist white students at their school (96). Like Danny, Jin has a crush on a beautiful white girl, Amelia, who in turn seems to be crushing on blond, curly-headed Greg. In one of the most notable and literally graphic instances of intertextuality in the book, Greg’s locks look remarkably like a stylized version of Danny’s hairdo, thus providing an important link between these two strands of the text. Jin, in turn, becomes convinced that the hair is key to his success with Amelia, and gets a perm (97–98). However, Suzy and Wei-Chen understand that this cosmetic transformation cannot undo their white classmates’ perceptions of them. Like Danny, Jin fails to recognize that while he can disown Chin-Kee, he can’t make him disappear.

Both Danny and Jin are damaged by other disempowering intertexts. For example, one of the ways in which Chin-Kee humiliates Danny is by singing Ricky Martin’s “She Bangs” atop a table in the school library. I knew the song, but not the allusion: as a student explained in her blog, this was a reference to the infamous audition by William Hung on American Idol in 2004, in which he massacred Martin’s song. Hung managed to parlay his fifteen minutes of reality-TV fame into an actual record deal, and his Idol audition has been viewed over 1.3 million times on YouTube. Documentary filmmaker James Hou claims that Hung “embodies all the stereotypes [Asian Americans] are trying to escape from”: that of the “ineffectual Asian-American male,” “complete with buck teeth, bad hair, and bad accent” (Guillermo,pars 24 and 4). The fact that Hung (and Chin-Kee) sing a song made famous by hip-shaking Ricky Martin compounds the irony, and the joke; as journalist David Ng explains, “When a squad of halter-topped dancers gyrate around [Hung] on national television, the resounding implication of course is that the object of their ‘lust’ is anything but sexy and desirable” (Ng, par. 1). The result, Ng says, is that such caricatures “make us all feel better about ourselves: men can act more manly,” and Asian Americans can distance themselves from Hung and “reinforce [their] own happily assimilated identities” (Ng, par. 4).

However, Yang’s novel reveals the self-destructiveness of that sort of thinking. Jin, too, tries to distinguish himself from Wei-Chen by telling him to “stop acting like such an F.O.B.” (89), even though in the eyes of some of their white classmates, the two are indistinguishable from each other. Jin finally discovers the truth of this when Greg tells him not to pursue Amanda anymore, realizing that Greg doesn’t even respect his masculinity enough to cushion the blow. Like the Monkey King, Jin’s realization generates fantasies of a comic-book-like showdown with Greg, but ultimately Jin’s anger is again internalized. Greg delivers the final blow by failing to recognize Jin’s homage to his own curly locks. The visual intertext about the hair that the reader got right away is invisible to Greg.

In addition to the film and television intertexts that connect these two parts of the novel, Yang also includes various forms of traditional children’s taunts and rhymes to link them. One instance of this kind of children’s folklore occurs when Jin, Wei-Chen, and Suzy are mocked by some white classmates for being “dog eaters” (32), a traditional racist taunt. These same white kids nonchalantly goad them, saying “It’s getting a little nippy out here,” so they should check for “gook bumps” (96). Suzy reflects the real damage caused by such casual humor when she tells Jin that “When Timmy called me . . . a chink, I realized . . . deep down inside . . . I kind of feel like that all the time” (187), though the boys never have such a breakthrough moment; they continue to use their pain to hurt each other, until eventually their friendship ends.

The graphic novel revisits this kind of children’s folklore in the “Chin-Kee” storyline, but here, it’s ostensibly played for laughs inside the bad sitcom-frame of this narrative thread. After some of Chin-Kee’s stereotypical antics, Danny catches a couple of white kids making slanty eyes and laughing (121), and in perhaps the text’s most irreverent and audacious instances of intertextuality, Chin-Kee reenacts the deplorable childhood rhyme “Me Chinese, me play joke, me go pee-pee in your Coke” (118), literally peeing in the Coke can of the high school’s most popular athlete.

Many students in my YAL class told me that they laughed out loud when they read that line, mostly in delighted surprise at their recovered memory of that childhood rhyme, but also out of seeing it presented literally in the text. I have to admit that the first time I read Yang’s graphic novel, I was amused, embarrassed, and shocked to see this bit of children’s folklore appear in the text; I remember hearing it on the school playground in early elementary school, and also remember being ashamed to recognize it as a part of my own folk repertoire when I came to the study of children’s folklore as an adult.

Yang seems to recognize that this folkloric intertext is lurking somewhere in the recesses of many of his readers’ memories and needs to be dredged up and confronted for what it is. While Chin-Kee’s enactment of the rhyme is presented humorously, the text frames it more ambiguously; literally, the panel where Chin-Kee tells Danny what he’s done to the Coke is framed by the sitcom’s canned “ha ha ha” laughter. This visual device encourages the reader to question whether this “joke” merits the laughter that it’s getting. By doing so, the text asks us to reflect on the unfunniness of the joke, and to consider the pernicious and lingering effects of seemingly innocuous texts. Of course, the novel takes a risk in recirculating the folk rhyme; it’s entirely possible that readers might just think it’s a funny reenactment of a bit of children’s folklore that they’d forgotten, and recite it afresh. But again, it’s the novel’s intertextuality that complicates this simplistic reading: by this point, the reader has witnessed Jin, Wei-Chen, and Suzy suffering as the result of other seemingly “innocuous” childhood taunts. In a way, then, Chin-Kee’s action can be read not just as another instance of his stereotypically comic antics, but as a potent act of revenge and subversion.

At this point, Yang’s disempowering intertexts begin to take on a more complex and empowering function. Far from being incidental to the plot, various characters’ rage about these stereotypical references is, in fact, what sets off the denouement of the novel. Chin-Kee’s “joke” and subsequent performance of “She Bangs” so enrage Danny that he beats Chin-Kee up. What ensues is yet another pop-culture intertext, as the fight between Danny and Chin-Kee becomes a protracted, comic-book version of a Kung-Fu movie, with Chin-Kee showing his superior skills via the “Kung Pao attack” and the “Happy Family head bonk” (208–209). This goes on for six pages, until Danny lands a lucky punch that knocks Chin-Kee’s bucktoothed head off, revealing his true identity as the Monkey King. The Monkey King tells Danny, “Now that I’ve revealed my true form, perhaps it is time to reveal yours” (213), and transforms him back into Jin. Here is where the metaphorical sense of the “Transformers” theme reenters the text: the two characters push and pull each other until they are both elevated into something entirely different and vastly more powerful.

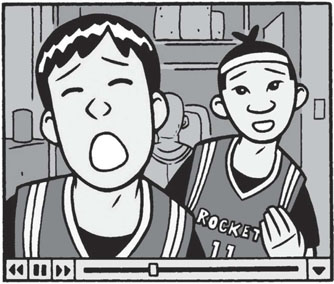

The Monkey King then reveals his relationship to Wei-Chen, and tells Jin that he “would have saved [him]self from five hundred years’ imprisonment . . . had I only realized how good it is to be a monkey” (223), thus urging Jin to reconcile with his own identity and with Wei-Chen. The two are eventually reunited, and the final image in the novel shows the two of them apparently in a video together. This, too, was a moment of intertextuality that was lost on me, but again my students recognized it as Yang’s comic rendering of a popular YouTube video featuring two Asian teenagers lip-synching to the Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It That Way.” Remarkably, while the William Hung video has been viewed only about a million times, this one has been viewed over nine million times since it was first posted several years ago, and has garnered more than 21,000 comments in that time.

Why does Yang end with this image? Younger, more astute readers could probably piece together a far more credible interpretation of the connection between this video and the characters of Jin and Wei Chen than I could, since they would be far more familiar with the context in which they first discovered and watched the original video. I can only speculate that, like the William Hung intertext, the YouTube image is supposed to again remind readers of the ways in which they might be complicit in perpetuating racial stereotypes: did they laugh at the original video? Think the performers were geeks, wannabees? And if the two singers are transformed into Jin and Wei-Chen, how do we look at the performance differently? Might we be able to see it as playful, sarcastic, mocking? The ambiguity of the novel’s final pop-culture intertext leaves readers on their own to make sense of the allusion—but as a result of having read the rest of the text, those readers have themselves been transformed into more agile and skillful interpreters of literature.

The Broader Use of Graphic Novels

This essay has explored the implications of one graphic novel’s potential to introduce students to the complex concept of intertextuality, while suggesting the ways in which that experience might enable students to think more critically and reflect more deeply on the text. In addition to being a writer of graphic novels, Yang is also a high school computer science teacher and an advocate of using comics of all kinds in the classroom, including classes beyond the language arts classroom. In fact, in an article written for Language Arts , Yang explains how he has even used graphic novels to teach algebra. His ability to negotiate the space between comics artists, teachers, scholars, and students makes Yang something of a one-man shuttle-diplomacy operation for new literacies. Consequently, teachers interested in learning more about the potential of comics in the classroom might enjoy perusing Yang’s website at http://www.humblecomics.com/comicsedu. The site includes an online version of his master’s thesis on comics in education, as well as other resources available for teachers interested in integrating this transformative art form into their own classrooms.

Rosemary V. Hathaway is an assistant professor of English at West Virginia University, where she teaches courses in folklore, young adult literature, and composition.

Notes

1. In fact, “The Raven” was featured in the original “Treehouse of Horror” episode of The Simpsons during the show’s second season (in October 1990).

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Image-Music-Text . London: Fontana, 1977. Print. “Chinese Backstreet Boys—That Way.” YouTube N.p. 25 Mar. 2009. Web. Accessed 11 July 2009.

Guillermo, Emil. “William Hung: Racism or Magic?” San Francisco Chronicle 6 Apr. 2004. SFGate.com 13 Mar. 2009.

Kristeva, Julia. Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art . Trans. Thomas Gora, Alice Jardine, and Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia UP, 1980. Print.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art . New York: Harper Perennial, 1994. Print.

Ng, David. “Hung out to dry.” The Village Voice 30 Mar. 2004. Web. Accessed 13 Mar. 2009. <http://www.villagevoice.com/2004-03-30/news/hung-out-to-dry?>.

Yang, Gene Luen. American Born Chinese . New York and London: First Second, 2006. Print.

———. “Graphic Novels in the Classroom.” Language Arts 85.3 (2008): 185–192. Print.