ALAN v37n1 - Breathing Underwater: At-Risk Ninth Graders Dive into Literary Analysis

Breathing Underwater:

At-Risk Ninth Graders Dive into Literary Analysis

I looked out at the English class before me, a group of 21 ninth graders deemed at-risk, and wondered if I was in over my head. Panic set in, and I reached for my life raft: Alex Flinn’s novel Breathing Underwater . I had met Judy Kitchner, their teacher, at a summer workshop where I had modeled teaching literary analysis to secondary students through close reading. The teachers enjoyed identifying all of the literary devices, discussing the effect of those devices, and writing an analysis of the author’s style, but some participants seemed skeptical. One even stated, “I really liked this activity, but I don’t think my ninth graders could do this. This is pretty high level stuff! I’m lucky if I can even get them to read a novel. Literary analysis and average or struggling ninth-grade students? I don’t see it happening!”

I had insisted that as long as teachers scaffolded the analysis activity, students of all levels could write literary analyses. To scaffold, teachers needed to (1) teach literary devices, (2) break analysis into small steps, and (3) allow students to work in groups at first. Not only did I insist all students could conduct literary analysis, I also extended an invitation, “If any of you would like me to introduce your students to literary analysis, I would enjoy the opportunity. All you need to do is to make sure that they know basic literary devices.” I was thrilled that Judy took me up on my offer.

I was pleased because I see too many students, especially students in Title I schools, drowning from the fatigue of navigating a school day that offers too little academic rigor. While this is a multifaceted problem, my experiences working in schools and with teachers lead me to believe that there are three main reasons why this is happening. As Kylene Beers poignantly reports in The Genteel Unteaching of America’s Poor , there are a number of teachers who have convinced themselves that there is a population of students who cannot withstand the demands of an academically challenging curriculum. These teachers limit their students to recalling and memorizing facts, to filling in blanks, and to working in isolation because they cannot handle the freedom of cooperative learning. “In the end,” writes Beers, “we are left with an education of America’s poor that cannot be seen as anything more than a segregation by intellectual rigor, something every bit as shameful and harmful as segregation by color” (3).

This segregation by intellectual rigor is advanced by the standardization of education. Proponents of accountability systems believe that if a teacher knows what goals to aim for and is equipped with the proper information, the teacher will be confident in his or her ability to increase student performance. To this end, students have been divided into lanes, and teachers have been equipped with a limited number of strategies with which to coach. Mathison and Freeman note that teachers feel that standardized testing drives classroom curriculum; they are compelled to teach to the test. Therefore, according to Grant and Hill, even teachers who want to uphold high academic expectations feel powerless to implement their own professional judgment. This creates an internal conflict between the mandated curriculum as demanded by districts’ accountability programs and teachers’ own professional diagnosis of what would best serve their students’ needs (Webb 5). The consequences of this conflict are that many teachers:

. . . are finding that their feelings about themselves, their students, and their profession are more negative over time. These teachers are susceptible to developing chronic feelings of emotional exhaustion and fatigue, negative attitudes toward their students, and feelings of diminishing job accomplishments . . . . (Wiley 81)

It is this stress over the legitimacy of their professional decisions that causes many teachers to corral their students into the shallow end of Bloom’s Taxonomy, despite the fact that research indicates that students need to swim out into the deeper waters of critical thought. It seems that the proponents of accountability want to pool students and force them to compete in a swim meet while research extols an exploratory field trip to the beach. I opted for the latter with Judy’s students, firmly believing that if you can swim in the ocean, the pool should pose no challenges.

Day 1: Wading into the Water: Introducing the Idea of Literary Analysis

I took a deep breath and waded in. “We’re going to start today with a freewrite. I have an unusual question for you—especially because you all don’t know me very well.” I heard the usual shuffling for paper, borrowing of writing utensils, annoyed sighs that the guest is actually making them write. “If you were dating someone and that person hit you—just once—would you stay with him or her, or would you end the relationship?”

I knew the question was too electric for students simply to start writing. Comments and questions erupted, and students began talking amongst themselves. Once they had verbally shared comments, they settled down and wrote for five minutes. Seven students reported that they would end the relationship, stating that “If he hits once, he will hit again . . . he might even kill you.” Eight students—all male but one—said they would stay with the person because everyone “deserves a second chance.” Four students wrote that it depended upon the situation. Every student wrote and then shared their ideas during the lively post-writing conversation.

Once the conversation ended, I held up the novel and told the class, “The reason I asked the question is because we are going to do an activity that relates to this book—Alex Flinn’s Breathing Underwater . It is about sixteen-year-old Nick Andreas. To his friends, Nick is one of the coolest guys in school; he’s handsome, rich, plays football, drives a convertible 1967 Mustang, and has a beautiful girlfriend named Caitlin. Caitlin knows the real Nick—the Nick whose mom walked out on him when he was five and left him with an abusive, alcoholic father who repeatedly tells Nick he’s a loser. As Caitlin and Nick’s relationship grows, so does Nick’s possessiveness. Nick begins to verbally and physically abuse Caitlin, until one final incident that results in Caitlin’s family getting a restraining order against Nick. At the hearing, the judge sentences Nick to a Family Violence class. This book is about Nick’s journey because of that class.”

The students began to ask if they would get to read the book, and I saw Mrs. Kitchner’s surprised look. They were already motivated because the novel centers on young adult characters and young adult issues. I continued to promote interest, “I like this novel because it’s just a good story. You pick it up to read and, before you know it, an hour has passed. It’s also well written. Flinn is a master at developing character and using language for effect. Finally, I like the novel because as much as I want to dislike the character of Nick, I can’t.” At this statement, students called out:

“How can you like a guy who hit his girl?”

“He sound like a spoiled rich kid to me.”

“No way, man.”

I explained, “Although Nick is a bad guy, Alex Flinn makes him a sympathetic character. Halfway through the novel, you realize that you want Nick to be happy and to overcome his past.”

“How can that be?” the students asked.

And that is how the lesson in literary analysis began.

Reflections on Day 1: The Selection of the Text

The selection of Alex Flinn’s Breathing Underwater was purposeful. Research reveals that adolescents are more engaged and motivated to read when they read young adult novels ( Ivey and Broaddus 2001 ; Pflaum and Bishop 2004 ). Literary analysis is cognitively demanding work; thus, I wanted the students to be heavily engaged with and invested in the story. Furthermore, Burdan (“Walking with Light” 123) recommends that students acquire the knowledge needed for literary analysis through the study of genres with which they are already familiar; and, young adult novels can promote the learning of literary elements and devices ( Hipple 2000 ; Salvner 2000 ). Flinn’s novel is particularly well-suited to literary analysis because she weaves literary devices seamlessly and effectually into her writing. Prior to selecting Breathing Underwater for this activity, I read seven of the ten finalists for the 2009 Heartland Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature, and none of them utilized literary devices as effectively. Additionally, I liked the fact that the protagonist of the novel is male. Judy’s lowest readers in class were males, bearing out what research has proven: schools are failing to meet the literacy needs of boys ( Newkirk 2000 ; Smith and Wilhelm 2002 ). Finally, in Classics in the Classroom: Designing Accessible Literature Lessons , Jago (2004) writes that “good” literature is literature that requires careful study, often guided by a teacher. The work Judy’s students and I did with Flinn’s novel certainly meets this definition.

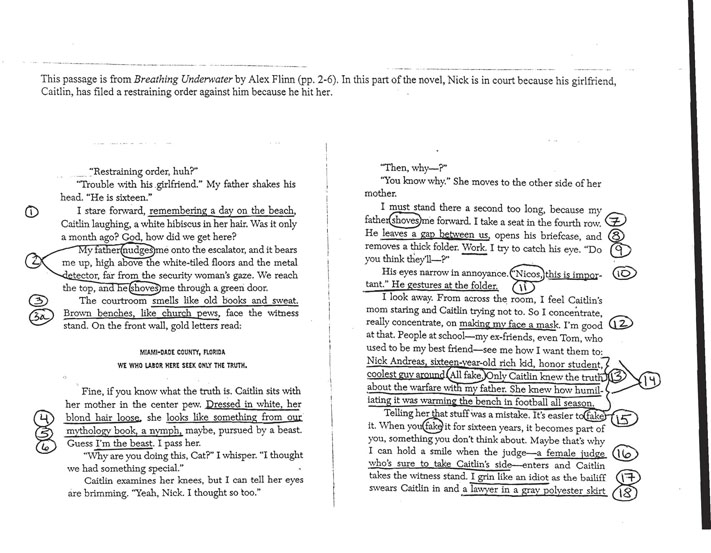

Day 2: Collecting Seashells: Identifying Literary Devices

I distributed a copy of four pages from the beginning of Breathing Underwater (Figure 1) and read it to the class. They listened with great interest. I then asked the students what their impressions were. They did not like Nick at all, and they felt sorry for Caitlin. “How can you be so certain?” I asked, “You’ve only read four pages of the book!”

They could not tell me why they felt this way, but they knew how they felt. I suggested, “Do you think it’s the way the book is written that makes you feel so strongly?” They were not buying it. “Think about it—a book is just like a work of art. Authors use techniques to create pictures and feelings. Let’s take a close look at this section of the book to see what Alex Flinn is doing to make us react so strongly to four pages of a book.”

I put an overhead transparency of the first two pages on the projector and read the first page aloud again. Then I guided them in a close reading. (All student names are pseudonyms.)

“In the third paragraph, Nick is ‘remembering a day on the beach’—what’s that called in the writing world when a character remembers back to something?”

“A flashback,” answered Brandon.

“Correct,” I agreed. “Why do you think Alex Flinn chooses to put a flashback in this portion? What does it do for the story, or what is the effect?”

The class looked at me for a few seconds, hoping I would answer my own question. Finally, Breshana offered, “It tell us that Nick and Caitlin used to have a good time together—before he started hitting her.”

“Yeah,” added Elias. “It even says Caitlin was laughing.”

“Man, things went wrong fast,” realized Valeria. “Laughing one month and in court with a restraining order the next.”

I summarized, “That flashback is doing a lot of work, isn’t it? It lets the readers know that at a point not too long ago, Caitlin and Nick were happy together. It gives you some of the background.”

“Let’s take a look at the next paragraph.” I read aloud again, then asked, “Is Flinn doing anything interesting in this paragraph?”

“She is letting us know that Nick’s dad is a hard*%#!” Felix blurted out. “Sorry, I couldn’t think of any other way to say it. The dude seems mean.”

“Flinn doesn’t say that he’s mean. What makes you think that?” I probed.

“The way he ‘shoves’ Nick,” answered Felix.

“Excellent, Felix. You noticed Flinn’s choice of verb there. She doesn’t use ‘pushes’ or ‘propels’ or ‘forces.’ She uses ‘shoves,’ and that tells us something, doesn’t it? That’s called diction , a fancy, literary way of saying “word choice.” In this case, it’s a strong verb. Are there any other good, strong verbs in that paragraph?”

“Well, at the beginning of that part, it says that Nick’s father ‘nudges’ him, but that’s not like a ‘shove,’” Kayla noticed. “A nudge is like a nice shove.”

The class laughed a bit at that statement. “You’re right, Kayla. Why do you think the father’s actions go from nudging to shoving? What happened to make him get angry as he and Nick rode up the escalator?”

“He didn’t get angry; the security guard just can’t see him anymore. He’s all Mr. Nice Guy around other people ’cause he don’t want people to know that he beat his son,” said Abismael, who rarely contributed aloud in class.

I let them know that their discussion was informing my understanding: “That is very perceptive, Abismael. I didn’t even catch that. Once he’s ‘far from the security woman’s gaze,’ he ‘shoves’ Nick. That’s pretty cool, huh? The fact that we can gather that much from the author’s choice to have a character go from nudging to shoving. Because of diction, we can infer—or form opinions—about characters based upon the evidence given to us by the author. So, who can summarize what we know about Nick’s dad, Mr. Andreas?”

“That he act one way in public and another way in private and that way ain’t nice,” stated Anquineshia with conviction.

Some students were engaged and getting into this close reading. Others were beginning to look a little bored, so I asked, “Do any of you all know people who act one way in public and another way in private?” The students began to share stories, and through this informal conversation, we got to know each other a bit better, helping to promote a positive learning environment and to re-engage those who had pulled back from the conversation. Burdan (“From Making Maps”) cautions that “there is a danger in allowing efferent reading to become the most valued mode of academic reading” (117) by subordinating it in importance to what Rosenblatt calls “aesthetic reading in which the reader gives attention to the sensations, feeling, and ideas evoked by the work as it is experienced” (33). According to Rosenblatt, truly active reading involves an engagement of the reader intellectually and affectively; both are crucial to transaction with the text.

I continued to read from the text, moving from “the courtroom smells like . . .” to “I pass her.” I paused and asked, “is there anything in this section you’d like to comment on?”

“There are two similes,” Jonathan noted.

“Two similes? Who can point out one of Jonathan’s similes?” I challenged the class.

Alyshia raised her hand, “The courtroom smells like old books and sweat and the benches are like church pews.”

“The courtroom smelling like books and sweat is not a simile,” corrected Scarlet. “A simile is when you compare two unlike things using like or as . The courtroom is not being compared to books and sweat; it smells like books and sweat.”

“You are right, Scarlet. The ‘benches like church pews’ is definitely a simile, but the courtroom one is not a simile. It’s another type of literary device. Who knows what it’s called?”

“Imagery,” Jessica offered.

“Yes, and to which of the five senses does this imagery relate, Jessica?”

“Smell,” said Jessica, sounding a bit bored.

“Yes, smell, or—if you want to make it sound fancy—you can say olfactory . The other five senses are sight, sound, taste, and touch, right? Well, they all have fancier terms. Sight is visual , sound is audial , and touch is tactile . Taste can also be called gustatory .”

“Gustatory,” repeated DeMarcus with an announcer’s voice. “I like that one.”

“Yes, gustatory. Fun to say, huh? So in this part of the text, we have an instance of imagery and a simile. What is the effect of the olfactory imagery of the courtroom smelling like old books and sweat?”

“That would not smell good, all musty and sweaty,” said Anquineshia, crinkling up her nose. “Maybe it show how they pack people into courtrooms, so it’s real crowded. And people are all hot and sweaty ’cause they’re nervous.”

“Good, Anquineshia. It certainly doesn’t make the courtroom seem like a place you want to be, does it? Now, what about the simile, ‘benches like church pews’?”

Jonathan raised his hand tentatively, “Well, it’s comparing the benches where the people sit in a courtroom to the pews in a church. Maybe that’s because a courtroom is kind of like a church, like a place where you get judged.”

Keona took issue with his statement, “You do not get judged at church, Jonathan. Church is a place to confess your sins and be truthful, not judged.”

I was surprised by the vehemence of her statement and by her posture. Keona had risen from her desk and was pointing angrily at Jonathan. I could tell that this could become a heated discussion, so to avoid a debate about the role of the church, I offered a compromise, “It’s okay if two people don’t see eye to eye on what something means. Remember, we are making inferences, meaning we’re trying to make educated guesses. Often, how we interpret something is going to be influenced by our life experiences. Some people may agree with Jonathan and others with Keona. That’s okay. Courtrooms can be affiliated with both—judgment and truth.”

I read the next section from “Fine, if you know what the truth is” to “Guess I’m the beast. I pass her” (2). Scarlet immediately blurted out, “Oh, there’s a metaphor. Nick compares himself to a beast. ‘I’m the beast.’”

“Good, Scarlet! How does that make you feel about Nick, that he compares himself to a beast?”

“I think it means that he knows what he did was wrong. It reminds me of Beauty and the Beast —how the beast doesn’t think he’s good enough for Belle,” said Scarlet, as others nodded their heads in agreement. I was happy that she made a connection to another text.

Before I had time to comment further, Alex asked, “What’s a ‘nymph’?” and I heard some giggling.

I ignored the giggles and said, “Well, in mythology, nymphs were beautiful, young female spirits of nature.”

“So, Nick thinks Caitlin is beautiful because he says she looks like one,” said Alex.

“Yes, he also says she is wearing white and has blond hair. Nymphs are often portrayed as wearing white. Does anyone know what the color white symbolizes?” I asked, feeling uncomfortable because I am speaking to a class with only three white students.

Shaquille raised his hand for the first time, and responded simply, “Purity.”

“That’s right, Shaquille. That’s why babies getting baptized and little girls getting confirmed and brides getting married wear white—because it means purity and innocence,” I added, relieved. “So, Nick is the beast, and Caitlin is the blond mini-goddess dressed in white. What effect does that pairing have, do you think?”

“It make him seem real bad and her seem real innocent,” DeMarcus said.

“DeMarcus, you are right. A big literary word to describe what Alex Flinn is doing here is called juxtaposition : putting two things close together to draw attention to how different those two things are or how similar they are. Juxtaposition.

“Juxtaposition,” De-Marcus said with a broad smile, and I saw that he was pleased to be “let in on” the secret language of literary analysis and to realize that it is not nearly so mysterious once you learn the process of constructing meaning and the associated terminology with which to describe it.

“Okay, the bell is about to ring on us, so we’re going to stop for the day. Tomorrow, you will be working in groups to identify some of the other literary devices Flinn uses on the next three pages,” I said loudly over the ringing bell and zipping of backpacks.

Reflection on Day 2: Encouraging Critical Thinking

The importance of Keona and Jonathan’s disagreement about interpretation is significant. Burdan states that many students are reluctant to engage in literary interpretation because “they doubt their authority to speak of the meaning of literature . . . [and] see themselves as observers, rather than participants in “the construction of knowledge” (“Walking with Light” 121).

Teaching students strategies to unlock literary analysis by identifying literary devices and investigating the effect of those devices enables teachers to promote the reading and interpretation skills students need to construct their own interpretations, thereby “freeing them from passively accepting their teachers’ interpretations” ( Rabinowitz and Smith 1998 , xv). At the same time, however, this strategy makes clear that it is the reader’s responsibility to attend to the author’s careful crafting of literary signs and to the conventions of the text. In other words, this strategy is a way to make public the thought process of expert readers and to illuminate the steps in the meaning-making process of literary analysis. Students of all abilities deserve the opportunity to think about and write in response to quality literature so they can learn to express their ideas with conviction grounded in a well-developed set of interpretive skills.

Day 3: Waist Deep with a Buddy: Fostering Cognitive Collaboration

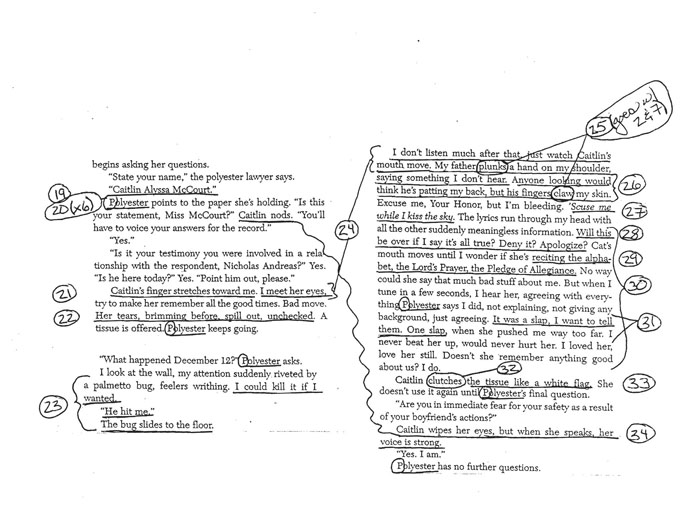

We began the third day by reviewing yesterday’s work. I facilitated this process by putting the first page of Figure 1 on the overhead and giving each student a handout titled “Reading with a Writer’s Eye” (see Figure 2), upon which I had listed the devices the students had discovered and discussed the day before.

I told the students, “You all did a great job yesterday. Today, I am going to put you into small groups and assign each group a portion of the passage. In your groups, continue identifying literary devices and discussing the effects of those devices. You will have twenty minutes to work on this. Then you are going to report, so make sure you record the information; mark it on the passage and write it on the “Reading with a Writer’s Eye” handout. When your group reports out, I want each person in the group to have at least one literary device to discuss.”

To ensure that each group had one student adept in identifying literary devices, I had pre-assigned groups the previous night and written them on an overhead. “Each group has a number that corresponds with the section of the passage I want you to focus on while you work today.” I circulated among groups and answered questions when asked. A few groups found something interesting in their passage, but could not think of a literary term for what they found. I informed the class that not everything had to have a literary term: “You can discuss anything you find interesting. If there is a literary term, I’ll let you know.”

At the twenty-minute mark, I stated, “Time is up. When your group comes up to the projector, underline the part of the passage you’re talking about on the overhead. Tell us what the device is and what the effect of the device is.” I modeled the process before beginning.

| Quote | Technique the author is employing | The effect of the technique |

|---|---|---|

| “remembering . . .” | flashback | gives us background; shows that Nick loved Caitlin |

| “nudges” to “shoves” | diction (word choice) | shows true character of father (nice in public, rough in private) |

| “smells like . . .” | olfactory imagery | paints an image letting us know that the courtroom is not a good place to be. People there are often sweaty due to nerves. |

| “like church pews . . .” | simile | draws comparison between church and court ( a place of judgment or a place of confession and truth?) |

| “Dressed in white . . .” | imagery and symbolism | portrays Caitlin as pure and innocent |

| “looks like . . . nymph . . .” | simile | comparison of Caitlin to a nymph portrays her as pure and innocent |

| “I’m the beast.” | metaphor and juxtaposition | contrasts Nick’s evil to Caitlin’s innocence; shows Nick’s remorse? |

Group one was assigned the portion of the passage from the spot where we ended yesterday to “He gestures at the folder” (6). The group discussed Flinn’s use of diction, imagery, syntax, dialogue, and the fact that Nick’s father calls him by his Greek name, “Nicos.” Each member in the group presented at least one literary device, naming it, showing where it was in the passage, and discussing the effect of the device. The other four groups presented as well.

All in all, the students found twenty-eight more literary devices in the passage to add to the seven we had found the day before. In the course of discussion, students learned the new terms of synecdoche and allusion . They also learned that not everything that makes an impact on a reader has to have a “fancy” literary term; sometimes, it is something as simple as syntax or repetition. Figure 3 is a compiled list of all of the devices the students identified.

As student groups presented their findings, class members recorded the information on their handouts. They also asked questions, challenged interpretations, and pointed out some overlooked devices. Students made connections among different parts of the text as well, citing the repetition of the word “fake” and the fact that Nick refers to the attorney as “Polyester” numerous times. They also noted that the negative portrayal of Mr. Andreas continues throughout the passage. Students led the discussion. I was a facilitator and had to interrupt their academic talk because the bell was about to ring.

I asked, “Do you think the judge is going to let Nick off?”

“No!” they said assuredly and almost in unison.

“Why not?” I probed as the bell rang.

“Because he’s ‘the beast,’” said Brandon.

| Breathing Underwater Literary Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|

| *synecdoche —a figure of speech in which a part represents the whole (wheels = car; hand = manual laborer) | ||

| 1 | “remembering” | flashback —gives us background; shows that Nick loved Caitlin |

| 2 | “nudges” to “shoves” | diction (word choice) —shows true character of father (nice in public, rough in private) |

| 3 | “smells like” | olfactory imagery —paints an image letting us know that the courtroom is not a good place to be. People there are often sweaty due to nerves |

| 3a | “like chuch pews” | simile —draws comparison between church and court (a place of judgment or a place of confession and truth?) |

| 4 | “Dressed in white” | imagery and symbolism —portrays Caitlin as pure and innocent |

| 5 | “looks like . . .nymph” | simile —comparison of Caitlin to a nymph portrays her as pure and innocent |

| 6 | “I’m the beast.” | metaphor and juxtaposition —contrasts Nick’s evil to Caitlin’s innocence; shows Nick’s remorse? |

| 7 | “shoves” | diction (word choice) —shows true character of father |

| 8 | “leaves a gap ” | literal and metaphorical imagery —shows the physical and emotional distance between Nick and his father |

| 9 | “Work.” | one word sentence(sentence structure) —draws attention to itself, showing Nick’s dislike of that fact that his father puts work first, even in a situation like this one |

| 10 | “Nicos” | Father’s use of full/real name —shows the seriousness of the situation; shows that Nick’s dad does not use the name Nick prefers |

| 11 | “this is important” | father’s dialogue —shows father putting work before son |

| 12 | “making my face” | metaphor —shows Nick putting on an act and hiding real feelings |

| 13 | “All fake.” | sentence structure —draws attention to the fact that Nick pretends to be what he is not |

| 14 | “Nick” vs. “Only” | juxtaposition —contrasts the image versus the reality; shows Nick’s trust in Caitlin |

| 15 | “fake” | repetition —use of the work “fake” three times shows how hard Nick worked to convince everyone that he was someone else; kept real self hidden |

| 16 | “a female judge” | sexism —shows that Nick does not trust females (thinks of mother) |

| 17 | “grin like an idiot” | simile —shows Nick continuing his act/fake; shows lack of respect |

| 18 | “a lawyer in” | visual imagery —describes the lawyer/Polyester become important |

| 19 | “Caitlin Alyssa” | full name —creates atmosphere of seriousness |

| 21 | “Caitlin’s finger” | visual imagery —creates a picture in our mind; shows accusation |

| 22 | “Her eyes” | visual imagery —creates a picture in our mind; shows Caitlin’s sadness |

| 23 | “I could kill” | content mirroring context —Nick hits the bug in anger like he hit Caitlin |

| 24 | “I meet” vs. “I don’t” | juxtaposition —Nick was attentive at first, now he zones out |

| 25 | “plunks” & “claw” | diction (word choice) —shows true character of father; also “plunks” is onomatopoeia |

| 26 | “Anyone would think” | truth versus reality —shows true character of Mr. Andreas |

| 27 | “Scuse me” | allusion —to a Jimi Hendrix song about escaping; shows Nick would like to escape |

| 28 | “Will this” | repetition of questions —Nick does not accept responsibility; he just wants this to be over |

| 29 | “reciting the alphabet” | listing —Nick thinks Caitlin is speaking in rote, not thinking about what she is saying. He associates her with positive thoughts: alphabet (childlike), Prayer (devotion), Pledge (loyalty) |

| 30 | whole page to this point | internal monologue —allows the reader to see Nick’s thoughts |

| 31 | “It was a slap” | repetition of “slap” —Nick does not see that he’s done anything wrong |

| 32 | Clutches | diction —shows Caitlin as being upset |

| 33 | “tissue like ” | simile and symbol —compares the tissue to a white flag, the symbol of surrender showing that Caitlin has given up (given up on love? Surrenders to her mother’s desire to press charges?) |

| 34 | “C. nods” vs.“C. wipes” | juxtaposition —in the beginning, Caitlin is too scared to speak aloud and nods instead; in the end, she is empowered and speaks with a “strong” voice. Shows Caitlin gaining strength |

Reflection on Day 3: Overcoming Learned Helplessness

The “Reading with a Writer’s Eye” handout provided not only a quick way to review, but also allowed the students to see the amount of high-quality work they had done. It also served as a graphic organizer upon which students could record their thought processes, so that they were not reliant upon me in the future. I was attempting to shift from a teacher-centered to a student-centered approach. Applebee (1992) cautions that this type of shift can be disconcerting to students, especially if they have been limited in the past to “narrowly defined comprehension skills” (9). Sadly, Applebee is alluding to the very same types of classrooms that Beers (2009) addresses in The Genteel Unteaching of America’s Poor .

Years of schooling that pose little academic challenge create a sense of learned helplessness in some students. Rarely being asked to share their opinions leads them to have little faith in their own ability to construct meaning and to be generative thinkers. Day three was an attempt to bolster students’ confidence, so they would feel competent to work without my assistance. This approach reflects research reported by Judith Langer (2002) in Effective Literacy Instruction: Building Successful Reading and Writing Programs . Langer discovered that effective literacy instruction (1) ensures that students learn procedures for approaching and completing literary tasks; (2) encourages generative learning by engaging students in creative and critical use of their knowledge; and (3) fosters collaborative cognition by having students work in communicative groups and participate in thoughtful academic dialogue where meanings are negotiated and constructed from multiple perspectives.

Day 4: Venturing into Deeper Waters: Putting the Pieces Together

I gave students the typed-up compilation of their work represented in Figure 3. As the students reviewed the list, I could tell that they were proud of their work. I was proud of their work, too, and it showed.

“We have done amazing groundwork for the next step. You have done an excellent job taking this passage apart and analyzing the pieces. We are now going to look at it as a whole. Remember when you were finding literary devices, I would not just let you find the device, but I also asked you to discuss the effect of the device?” Students nodded. “Well, now I want you to look at all of the devices you’ve found and answer this question: what do you think Flinn intended for this passage to do for the novel as a whole? Before you start to think about it, though, I’ll give you a hint. Usually, an author is working to establish plot or character or setting or conflict. What is Flinn doing here? The best thing about this question is that there is more than one right answer. Discuss this with your shoulder partner for about three minutes before I call on you to share your ideas. When you’re thinking and talking, try to complete this sentence: The main purpose of this passage in the novel as a whole is to__________________ .”

At the three-minute mark, I asked for volunteers to share their hypotheses. Here are some of their responses.

“The main purpose of the passage in the novel as a whole is to:

- develop the character of Nick as angry and confused.

- show that sometimes life has hard lessons to learn.

- inform the reader of the background of the novel.

- show how Nick’s father’s mistreatment of him starts a vicious cycle.

- develop the conflict between Nick and his father.

As we discussed their responses, I asked students to explain their assertions, and they supported their ideas with the literary devices they had identified. They justified their answers and expressed them confidently. For instance, the group that stated that the main purpose of the passage was to develop the conflict between Nick and his father cited the following textual support for their assertion: (1) the choices in diction of Mr. Andreas going from “nudging” Nick to “shoving” him; (2) Mr. Andreas literally and figuratively “leav[ing] a gap” between himself and his son; (3) the emphasis of the one-word sentence “Work.”; (4) Mr. Andreas calling Nick “Nicos”; (5) Mr. Andreas putting his work above Nick; (6) Mr. Andreas’s fingers “claw[ing]” Nick and “plunk[ing]” down on him; and (7) the difference in the way people view Mr. Andreas versus his true character. This is the outline of a highly effective literary analysis from students who had never previously been asked to do literary analysis.

Conclusion

Studies by both Langer (1995) and Wilhelm (1997) of what good readers do when they read indicate that good readers enter the story world by evoking visual images. Effective readers interact with the text, predicting what will happen next. They develop relationships with the story’s characters, and they make connections between the action and characters in the story with events from other texts and their own lives. They are reflective. Good readers ask analytic evaluation questions about how the story is told, recognizing literary conventions and their significance, as well as the role of the author in the writing of the story and the role of the reader in assigning meaning. Making this interactive, meaning-making process transparent to our students dispels their notions that reading is a passive process and allows them access into the dialectic and dynamic world of transactional reading. If we scaffold literary analysis for our struggling students, they, too, can venture into the deeper waters of critical thought to discover worlds previously unknown to them.

Anete Vásquez is an instructor at the University of South Florida in the Department of Secondary Education, where she teaches English education methods courses and coordinates field experiences. Dr. Vásquez’s research interests include adolescent literacy, teacher efficacy, and the preparation of responsible secondary education teachers. She is coauthor of Teaching Language Arts to English Language Learners . Before working in higher education, Dr. Vásquez taught secondary English for fourteen years.

Works Cited

Applebee, Arthur. “The Background for Reform.” In Literature Instruction: A Focus on Student Response . Ed. Judith Langer. Urbana: NCTE, 1992. 1–18. Print.

Beers, Kylene. The Genteel Unteaching of America’s Poor. National Council of Teachers of English . NCTE, 4 Mar. 2009. Web. 11 July 2009. Web.

Burdan, Judith. “Making Maps: Helping Students Become Active Readers.” Academic Literacy in the English Classroom: Helping Underprepared and Working Class Students Succeed in College . Ed. C. Boiarsky. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2003. 106–119. Print.

Burdan, Judith. “Walking with Light: Helping Students Participate in the Literary Dialogue.” Academic Literacy in the English Classroom: Helping Underprepared and Working Class Students Succeed in College . Ed. C. Boiarsky. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2003. 120–130. Print.

Flinn, Alex. Breathing Underwater . New York: HarperCollins, 2001. Print.

Grant, Michael, and Janette Hill. “Weighing the Risks with the Rewards: Implementing Student-Centered Pedagogy within High Stakes Testing,” Understanding Teacher Stress in an Age of Accountability . Ed. Richard Lambert and Christopher Mc-Carthy. Charlotte: Information Age, 2006. 19–42. Print.

Hipple, Ted. “With Themes for All: The Universality of the Young Adult Novel.” Reading Their World: The Young Adult Novel in the Classroom . Ed. Virginia R. Monseau and Gary M. Salvner. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2000. 1–14. Print.

Ivey, Gay, and Karen Broaddus. “‘Just Plain Reading’: A Survey of What Makes Students Want to Read in Middle School Classrooms.” Reading Research Quarterly 36.4 (2001): 350–377. Print.

Jago, Carol. Classics in the Classroom: Designing Accessible Literature Lessons . Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2004. Print.

Langer, Judith. Envisioning Literature: Literary Understanding and Literature Instruction . New York: Teachers College Press, 1995. Print.

Langer, Judith. Effective Literacy Instruction: Building Successful Reading and Writing Programs . Urbana: NCTE, 2002. Print.

Mathison, Sandra, and Melissa Freeman. “Teacher Stress and High Stakes Testing: How Using One Measure of Academic Success Leads to Multiple Teacher Stressors.” Understanding Teacher Stress in an Age of Accountability . Ed. Richard Lambert and Christopher McCarthy. Charlotte: Information Age, 2006. 43–64. Print.

Newkirk, Thomas. “Misreading Masculinity: Speculations on the Great Gender Gap in Writing.” Language Arts 77.4 (2000): 294–300. Print.

Pflaum, Susanna W., and Penny A. Bishop. “Student Perceptions of Reading Engagement: Learning from the Learners.” Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 48.3 (2004): 202–213. Print.

Rabinowitz, Peter, and Michael Smith. Authorizing Readers: Resistance and Respect in the Teaching of Literature . New York: Teachers College Press, 1998. Print.

Rosenblatt, Louise. Literature as Exploration . 5th ed. New York: MLA, 1995. Print.

Salvner, Gary M. “Time and Tradition: Transforming the Secondary English Class with Young Adult Novels.” Reading their World: The Young Adult Novel in the Classroom . Ed. Virginia R. Monseau and Gary M. Salvner. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2000. 85–99. Print.

Smith, Michael, and Jeffrey Wilhelm. “Reading Don’t Fix No Chevys”: Literacy in the Lives of Young Men . Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2002. Print.

Webb, P. Taylor. “The Stress of Accountability: Teachers as Policy Brokers in a Poverty School.” Understanding Teacher Stress in an Age of Accountability . Ed. Richard Lambert and Christopher McCarthy. Charlotte: Information Age, 2006. 1–18. Print.

Wiley, Carolyn. “A Synthesis of the Research on the Causes, Effects, and Reduction Strategies of Teacher Stress.” Journal of Instructional Psychology 27.2 (2000): 80-87. Print.

Wilhelm, Jeffrey. “You Gotta BE the Book:” Teaching Engaged and Reflective Reading with Adolescents. New York: Teachers College Press, 1997. Print.