“Why Do Chinese People Have Weird Names?” The Challenges of Teaching Multicultural Young Adult Literature

The importance of including multicultural literature in U.S. secondary classrooms has been increasingly recognized in the recent decade. Preparing teachers to instruct culturally and linguistically diverse students is a popular concern in teacher education, and a great quantity and quality of literature can be found centering on the applications of multicultural literature in U.S. schools. Some commonly discussed issues include the enhancement of teachers’ cultural awareness so they can better address that of their students (Athanases; Gove & Benjamin; Lowery & Sabis-Burns; Stallworth, Gibbons, & Fauber; Zygmunt-Fillwalk & Clark), take advantage of the various pedagogical approaches or theoretical backgrounds important to teaching literature from diverse cultures (Appleman; Cai, Multicultural Literature , “Transactional Theory”; Dong; Ernst-Slavit, Moore, & Maloney; Hunt & Hunt; Langer; Rogers & Soter; Simmons & Deluzain), and be familiar with the myriad criteria for selecting quality multicultural literature for classroom use (Gates & Hall Mark; Hinton; Landt; Loh; Louie; How to Choose ). These discussions and debates concerning the role of multicultural literature in the secondary school curriculum have deepened understandings of literature from diverse cultures and the benefits it brings to the education of all students.

However, as literature teachers, English educators, and researchers, we have noticed that integrating multicultural literature in actual classrooms seems easier said than done for many practitioners. Many teachers find it challenging to weave multicultural literature into the curriculum for various reasons, including lack of time, curricular restraints, lack of community support, and lack of interest among students. Without doubt, new perspectives and ideas about the benefits of teaching multicultural literature continue to be of interest to researchers and theorists; however, the question remains: how does the high school teacher “in the trenches” translate these ideas into day-to-day classroom practice?

In this article, our goal is to address the concerns of teachers with whom we have worked who teach in a predominately rural, Midwestern region of the US and who struggle with integrating multicultural young adult literature into their largely homogenous classrooms of White, middle class, American-born students. First, we will describe the concerns of these teachers as they were expressed in various informal interviews with us. Then, we will describe a classroom observation in a very different kind of instructional setting—a high school ESL class containing students from five different countries and at least three different continents—in which a multicultural young adult novel, Yang the Youngest and His Terrible Ear , by Lensey Namioka, is effectively used. We believe analysis of this classroom observation sheds light on the concerns of the teachers with whom we’ve worked, providing possible solutions to the challenges they face when sharing multicultural literature and associated cultures with their students. Finally, we will share additional theoretically and philosophically consistent pedagogical strategies for teaching another multicultural YA text, American Born Chinese , by Gene Luen Yang.

Common Obstacles to Teaching Multicultural Literature

“I’d Love to Teach Multicultural Literature, but . . .”: Challenges from and Guidelines for the Classroom Teacher

As mentioned earlier, despite the many theoretical and research-based arguments for including multicultural literature in the secondary school curriculum, specifically multicultural young adult literature, carrying out such curricular integration can be a challenge for many teachers. The most widely self-reported and discussed issue is teachers’ lack of knowledge of works from different cultures. Based on their own past schooling experiences, many middle class, White school teachers have a profound knowledge about literature in the European canon (Gove and Benjamin; Hunt & Hunt; Stallworth, Gibbons, and Fauber), but limited experience with literature from other cultures. A large population of these teachers, therefore, either holds on to the belief that only books written from a Western perspective are worthy of study, or they confess to not knowing the criteria for selecting quality multicultural literature.

For teachers who lack such a sense of cultural awareness, Zygmunt-Fillwalk and Clark suggest that people need to understand their own cultural selves before recognizing and understanding the cultures of others. This type of reflection could begin by examining one’s own cultural heritage, values, and beliefs and recognizing them as part of a multifaceted teacher identity, including multiple personal and professional subjectivities. (See Appendix 1 for a checklist for engaging in such reflection.) As for how to select literary works by diverse cultural groups, we have assembled some scholarly advice (Cai, Multicultural Literature ; Landt; Loh; Louis; How to Choose ):

- Check the background of the author. It takes sufficient knowledge and experience within a culture to present its beliefs, customs, and values accurately and authentically.

- Look for appealing plots and characterizations. After all, a good storyline and well-developed characters are what catches readers’ attention.

- Make sure that at least some of the characters representing diverse cultures are portrayed in a positive light. Characters from diverse backgrounds should be empowered to solve problems of their own instead of only playing subservient roles while Whites serve dominant roles.

- Select works in which realistic social issues and problems are depicted frankly, without oversimplification.

- Assess whether cultural features and icons are depicted truthfully in texts and illustrations—not only the physical characteristics like clothing, but relationships among people within and across cultures.

- Browse websites of award-winning multicultural children’s and YA books to maintain timely knowledge of available first-rate literature.

We feel confident that teachers who follow these suggestions will find a rich supply of resources. Notable awards given for quality children’s and young adult multicultural literature are listed in Appendix 2.

“I Feel Very Tied to Teaching the Standards”: What Nine Real Teachers Had to Say about Teaching Multicultural Literature

In a continuing effort to explore the challenges real teachers face when implementing multicultural YA literature in their classrooms, we interviewed nine middle school and high school teachers in the winter of 2009 about their experiences teaching multicultural literature. We asked them several questions focusing on their teaching context, their preparation to teach, and their experiences teaching multicultural literature, both successful and challenging.

The ethnic identities of the nine teachers were either White or Asian. Their students came from a variety of backgrounds, but they were predominately White and middle or working class. These teachers cited many challenges when teaching or attempting to teach multicultural literature, which we have organized into several thematic categories, such as “lack of cultural knowledge,” “creating relevancy for the text,” and “lack of parental support.” We have summarized the challenges they described in the Figure 1 and included some key quotations from their interviews.

| Category | Challenges | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher | Lack of cultural background | Teachers don’t always have a well-rounded knowledge about a culture. | “I was also afraid I might have conveyed to students information or feelings irrelevant to the culture we were studying.” |

| Create relevancy of the text | Teachers find it challenging to help students see the relevance of the text introduced. | “Since the vast majority of students are White and from middle class families, they find it difficult to identify with characters who do not live similar experiences and/or have similar belief systems.” | |

| Parents | Lack of parental support | Parents are not familiar with literature that is not part of the traditional Western canon. | “Often, the parents must be convinced that multicultural literature is valuable, useful, and a necessary aspect of their children’s education.” |

| School | Time/Curriculum | Tight curriculum schedule makes it hard to squeeze in extra materials. | “It is difficult to find multicultural pieces for which I can do justice in a short span of time.” |

| Teach to the standard | School and educational policy restrict teachers’ choice of extra materials. | “I feel very tied to teaching so many standards that I must use a lot of what is in the literature book, and that leaves little time for reading novels and other outside sources.” | |

| Censorship | The school board gives restrictions on teachers’ choice of materials. | “Censorship is an issue, though, at the school where I taught. They were very traditional and conservative and would prefer to avoid any controversial texts.” |

The most commonly cited challenges were lack of parental support/understanding, lack of time, creating relevancy for the text within a classroom of students who may not be able to easily “identify” with diverse characters, censorship or the possibility of censorship, lack of personal background knowledge about the culture portrayed in the book, feeling restricted in their teaching by curricular and state standards, and the limiting nature of literature anthologies. Representative comments include the following:

“What I find most challenging when using multicultural literature is working it into our strict curriculum. Since the vast majority of students are White and from middle class families, they find it difficult to identify with characters who do not live similar experiences and/or have similar belief systems” (interview, February 23, 2009).

“I feel very tied to teaching so many standards that I must use a lot of what is in the literature book, and that leaves little time for reading novels and other outside sources. Not to mention all the standardized testing, ISTEP twice this year and a new acuity computer-based program, three times this year. When I do get to read a novel with my class, I have to look at the 6th-grade corporation’s reading list and choose from it. Then, I try to take into consideration what they [students] will relate to” (interview, February 23, 2009).

These teachers clearly experience multiple challenges when thinking about teaching multicultural young adult literature. For the purposes of this article, we will focus primarily on the challenge of building relevancy and interest for multicultural books among students from homogenous, often White, middle class backgrounds.

Putting Students at the Center: A Case Study

As we analyzed the interview data, we realized one of the teachers interviewed was quite different from the others. Gloria reported very positive experiences teaching multicultural literature in her 9th- and 10th-grade classroom. She stated,

I’m not sure these were “successful” experiences, but every time I taught multicultural literature in my classroom, my students seemed to be interested. Sometimes we would put stories to dramas/plays and act out. Sometimes we drew pictures about the stories. Sometimes we would watch films of the same titles of the books (interview, February 11, 2009).

One difference between Gloria’s class and the classes of the other eight teachers is that her class was truly multicultural itself: she had students from at least five different countries and three continents. Perhaps this difference alone was enough to increase the students’ interest in multicultural literature. However, students were not always reading literature from their own cultures; they often read literature that depicted experiences quite alien from their own lives, just as the students in the other small, midwestern schools near our university. Nonetheless, Gloria reported great success teaching diverse books to her students.

In our continuing effort to discover novel ways for teachers to approach the teaching of multicultural young adult literature, particularly with resistant adolescents, we decided to observe Gloria teaching a YA novel about an Asian pre-teen. Yang the Youngest and His Terrible Ear tells the story of a young boy, Yingtao, who moves to America with his musically talented family only to discover that he himself does not possess the musical gift. Yingtao’s experiences trying to integrate into a new culture while also trying to fit into his own family are depicted with humor and insight by author Lensey Namioka, who was herself born in China and later emigrated to the U.S. as a child.

To more closely examine the teaching of this multicultural YA book in Gloria’s class, we observed and videotaped a class session in which students discussed Chapter 4 of Namioka’s book. We also read Gloria’s written reflections on the class after it was completed, as well as students’ response journals. The varying sources of information helped us to see how an experienced teacher might successfully integrate multicultural literature into the high school curriculum in ways that make the text relevant for a diverse group of student readers, none of whom share the same cultural identity as the novel’s protagonist.

When teaching this novel, Gloria made a great deal of effort to connect her students’ lives to that of Yingtao, even though many of them had never been anywhere near China (students were from the Philippines, Burma, Mexico, Sudan, Vietnam, Haiti, Thailand, and Guatemala). In a classroom that seemed open, friendly, and nonjudgmental, Gloria engaged students in a discussion of Chapter 4, in which Yingtao visits the home of his new friend Matthew. During this visit, Yingtao struggles with many American expressions and cultural realities, including part-time jobs, being “laid off” from work, what it means to be a “nerd,” and the difficulty with foreign names. Gloria’s class discussed all of these aspects of the chapter while trying to connect them to their own experiences. At one point in the class discussion, a student from Africa asked an important question: “Why do Chinese people have weird names?” Instead of silencing this question and chastising the questioner, Gloria used this as an opportunity to explore language difference: “It is true that anything new to you might seem weird. Wouldn’t it be possible for a Chinese man to think African names are weird and hard to pronounce?” The student agreed that this was a possibility.

Belinda Louie, in “Guiding Principles for Teaching Multicultural Literature,” lists several guiding principles for helping students respond to multicultural literature, including several related to building empathy for others unlike yourself and seeing the world through the perspectives of the characters (439). Gloria seems to build her literature curriculum around this idea of empathy building by consistently asking her students to simultaneously consider the text from both their own perspective and the perspective of the characters. When thinking about why her class might be having such a positive experience with multicultural literature, we began to view her approach to the teaching of literature as a variation on the traditional reader-response-based strategy of asking first for student personal response, then moving to interpretation and analysis. In this case, however, Gloria does not see personal response as the first stop on a linear road to having a literary experience; instead, she perceives it is an ongoing part of the reading process that places the text in the center, as a mediator between the student reader and the culture he/she is reading about. This concept is made visible in Figure 2.

In this model of the reading process, the multicultural young adult text not only mediates between an adolescent’s dual experiences as “adult” and “child,” it also introduces the teen reader to other cultures and peoples (i.e., context) by acting as a focus of conversation and reflective thought. As happened when we observed Gloria’s class, the novel was always the center of the discussion; however, Gloria constantly used the text as a bridge to discussions about other cultures and the students’ own lives. When she could demonstrate connections between the reader and the context through the YA text, she succeeded in building student interest in the novel as well as an understanding of its relevancy to their lives. Selected quotations from the students’ reader-response journals demonstrate such bridge building at work. In these writings, Yingtao’s experiences learning about aspects of American culture—part-time jobs and the importance of sports, for instance—made it possible for students to connect with similar experiences of their own:

Jose writes, “For me, playing soccer is so important. When I have to go to another place to play and when I tell my dad sometimes to get me there, he will say, ‘I have to do something more important,’ and he says playing soccer is not so important.”

Taran writes, “Even if someone offers me a part-time job, I will not take it now. I think the part-time job will be in the shops or restaurants, or haircutting or doing nails, and they will not pay me much money.”

Clearly, these students are making intimate connections between the novel and their own lives.

After such analysis of Gloria’s teaching, we began to wonder if what we learned from her classroom might be applied to other secondary school classes in which students read multicultural YA novels about settings and characters very unlike themselves. Therefore, we took what we learned and imagined how a similar teaching philosophy might look when applied to another popular multicultural YA text, American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang.

Keeping Students’ Lives at the Center: American Born Chinese

American Born Chinese differs from other books by and about Chinese Americans. Not only is it a graphic novel, but it is also the first graphic novel to both win the Michael Printz Award (in 2007) and be nominated for the National Book Award (also in 2007). Gene Luen Yang is of Taiwanese origin, although he grew up in the U.S, and he incorporates his personal life experiences as a Chinese American into the plot of American Born Chinese . His struggles with cultural identity, fitting in at school, coming of age, and relationships with the opposite sex will resonate with teenagers from many backgrounds.

Suggested Pedagogical Activities for American Born Chinese

Reader-centered teaching is consistent with the goals of constructivist education (Appleman 26). Students are the creators of meaning through their transactions between personal background and the text; these transactions also help to change the power dynamics of the classroom (Rosenblatt 40). With this in mind, we can envision introducing this book in the following ways.

Activity I

Before having students read the book, give them a book talk. Start a discussion about the genre of the book (a graphic novel) and its cover layouts. Then introduce students to the structure of the book, which contains a juxtaposition of three storylines. Ask about students’ previous knowledge of the Chinese culture, either from their own experience or what they’ve learned from the media. Introducing the main characters that appear on the cover pages can give students a sense of what to expect.

Also depicted on the book’s cover are a melancholy, black-haired boy holding a transformer; a bucked-tooth, slant-eyed, yellow-skinned Chinese man in traditional costume; and an irritated monkey buried under a huge pile of crushed rocks. By introducing them as major characters in the three stories, the teacher can then ask students to predict what might happen to these characters based on the visual clues (facial expressions, their poses, the title, the settings, etc.).

Activity II

When students are reading the graphic novel, ask them to keep track of the cultural icons depicted throughout the book. This can be used later as the basis for a discussion about the cultural features of the text and the difficulties students might encounter as cultural outsiders reading this piece of literature. In addition, it would be a good way to gauge students’ sensitivity to cultural difference. Later, they could be divided into groups and asked to write on the board the visual and textual cultural icons they found in the novel. After students list all these features, the teacher can intervene to determine if students can distinguish between an icon (positive representation) and a stereotype (negative image). For instance, one of the main characters, Cousin Chin-Kee, is the concoction of all the negative stereotypes associated with Chinese characters. Through the stereotyped Cousin Chin-Kee, we can see how Yang deals with racism and stereotypes in an ironic, and often humorous, way. Quoting his explanation of the creation of this controversial character, Yang ( Gene Luen Yang ) maintains:

There is always the danger, of course, that by making a comic book about Cousin Chin-Kee I’m helping to perpetuate him, that readers—especially younger readers—will take his appearance in American Born Chinese at face value. I think it’s a danger I can live with. In order for us to defeat our enemy, he must first be made visible. Besides, comic book readers are some of the smartest folks I’ve ever met. They’ll figure it out.

In fact, the uneasiness or disturbance students might have while reading about this character can serve as a superb opportunity to discuss such cultural stereotypes ( Yang, n. d. ).

Activity III

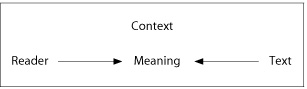

Next, a teacher might utilize Appleman’s Reader-Response Diagram (see Figure 3) as a tool to investigate students’ reflections on the story and the meanings they constructed from reading.

On the “reader” end, students are to consider what personal characteristics, qualities, or elements of their personal histories could be relevant to their reading of this specific graphic novel. For example, “I have (have not) read the Monkey King tale before. I have (have not) eaten Chinese food before. I’ve read stories about Chinese/Chinese Americans in . . . .” Such reflection helps the students to see which parts of their past experiences are contributing to their responses to this novel. Then on the “text” end, they might be asked to discuss the textual/visual aspects of the novel that could affect their reading or response. For instance, “It’s in a comic format. Texts are mostly dialogues. Chinese words are included,” etc. Such characteristics of the literary work also play a part in affecting a reader’s responses to the novel. For the “context,” it would be interesting for students to reflect on where and how they are reading the story. Is it out of school? Is it in school? During any specific emotional condition or experience? Did they read it in one sitting? Finally, as to the “meaning” section, students could record their strongest responses to the novel in writing. After reading all the responses from students, the teacher might lead a more comprehensive class discussion about the impacts of personal experience and textual representations on a reader’s understanding of a particular literary work.

We believe that activities such as these that focus on how texts can reflect and affect the lives of student readers have the potential to help teachers feel more comfortable and confident using multicultural literature in their classrooms.

Mediating the Ongoing Challenges of Multicultural Education through YA Lit

We hope that this article has given practicing teachers some ideas about how to ameliorate the very real challenges of teaching multicultural literature in the secondary classroom. We have found that using young adult literature to introduce our often homogeneous students to diverse cultures can be quite effective—particularly when coupled with literature pedagogies, such as those above, that place texts at the center of a literary experience connecting the student reader with a world he or she has not experienced firsthand. In this way, reading YA lit can become part of a personal–cultural transformation that can help student readers become more empathetic, thoughtful, and communicative citizens in, as Friedman refers to it, our “flat” globalized world.

We have focused on two wonderful multicultural texts, Yang the Youngest and His Terrible Ear and American Born Chinese . However, we know there are many more examples of multicultural YA texts that a secondary teacher might incorporate into the curriculum, so we have included a few of our favorites in Appendix 3. No matter what book or books teachers choose to use, we encourage them to always see the literary experience as a way to transform the adolescent reader.

Nai-Hua Kuo is a doctoral student in the Department of Curriculum & Instruction at Purdue University in Indiana. Her research interests include children’s and young adult literature, teacher education, and multicultural education. She is currently a graduate assistant for First Opinions, Second Reactions —a Purdue-sponsored e-journal that reviews children’s and young adult literature.

Janet Alsup is associate professor of English Education at Purdue University. Her specialties are teacher education and professional identity development, the teaching of composition and literature in middle and high schools, critical pedagogy, young adult literature, and qualitative and narrative inquiry. Her first book, coauthored with Dr. Jonathan Bush, is titled But Will It Work with Real Students? Scenarios for Teaching Secondary English Language Arts (NCTE, 2003). Her second book, Teacher Identity Discourses: Negotiating Personal and Professional Spaces (Erlbaum/NCTE), was published in 2006 as part of the NCTE/LEA Research Series in Literacy and Composition.

Appendix 1

How Does Our Own Cultural Perspective Shape Our Thinking, Actions, and Teaching?

- Where were you born?

- What language(s) or dialect(s) were spoken in your home?

- Where did you grow up?

- What are people in your neighborhood like? Where are they from?

- What is your ethnic or racial heritage?

- Was religion important during your upbringing? If yes, how?

- Who makes up your family?

- What traditions does your family follow?

- What values does your family hold dear?

- How do the members of your family relate to each other?

- Has racial difference ever impacted your life? When?

(Adapted from Hinton, 2006 p. 52)

Appendix 2

| Award Title | Focus |

|---|---|

| Americas Award for Children’s and Young Adult Literature | Latin Americans |

| Pura Belpre Award | Latin Americans |

| Tomás Rivera Book Award | Mexican Americans |

| Carter G. Woodson Award | Ethnic Minorities |

| Coretta Scott King Book Award | African Americans |

| Batchelder Award | Outstanding Foreign Language Children’s Books Translated into English |

| Jewish Book Council Children’s Literature Award | Jewish |

| Sydney Taylor Book Award | Jewish |

| Asian Pacific American Award for Literature | Asian/Pacific Americans |

| AsianAmericanBooks.com | Asian Americans |

| Amelia Bloomer List | Women in all Ethnic or Social–Economic Backgrounds |

| Great Graphic Novels for Teens | Graphic Novels and Illustrated Nonfiction for Ages 12–18 |

| Native Writers Circle of the Americas | Native Americans (not limited to YA literature) |

Appendix 3

Additional Multicultural YA Novels for Classroom Use

Curtis, Christopher Paul. Elijah of Buxton . New York: Scholastic, 2007. Print.

Myers, Walter Dean. Street Love . New York: Amistad, 2006. Print.

Alexie, Sherman. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian . New York: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2007. Print.

Park, Linda Sue. A Single Shard . New York: Clarion, 2001. Print.

Frost, Helen. Keesha’s House . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003. Print.

Nelson, Marilyn. Carver: A Life in Poems . Honesdale, PA: Front Street, 2001. Print.

Lester, Julius. Day of Tears: A Novel in Dialogue . New York: Hyperion, 2005. Print.

Nye, Naomi Shihab. Habibi . New York and Logan, IA: Perfection Learning, 1999. Print.

Draper, Sharon. Tears of a Tiger . New York: Simon Pulse, 1991. Print.

Taylor, Mildred D. The Well: David’s Story . New York: Puffin, 1998. Print.

Kadohata, Cynthia. Weedflower . New York: Antheneum, 2006. Print.

Na An. A Step from Heaven . Honesdale, PA: Front Street, 2001. Print.

Yee, Lisa. Millicent Min, Girl Genius . New York: Arthur A. Levine, 2003. Print.

Namioka, Lensey. April and the Dragon Lady . Bel Air, CA: Browndeer Press, 2004. Print.

References

Appleman, Deborah. Critical Encounters in High School English: Teaching Literary Theory to Adolescents . New York: Teachers College Press, 2000. Print.

Athanases, Steven Z. “Deepening Teacher Knowledge of Multicultural Literature through a University–Schools Partnership. Multicultural Education 13.4 (2006): 17–23.

Cai, Mingshui. Multicultural Literature for Children and Young Adults: Reflections on Critical Issues . Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press, 2002. Print.

Cai, Mingshui. “Transactional Theory and the Study of Multicultural Literature.” Language Arts , 85.3 (2002): 212–220.

Dong, Yu R. Taking a Cultural-Response Approach to Teaching Multicultural Literature. English Journal , 94.3 (2005): 55–60.

Ernst-Slavit, Gisela, Monica Moore, and Carol Maloney. Changing Lives: Teaching English and Literature to ESL Students. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 46.2 (2002): 116–128.

Friedman, T.L. The World is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century . New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2005. Print.

Gates, Pamela S., and Dianne L. Hall Mark. Cultural Journeys: Multicultural Literature for Children and Young Adults . Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2006. Print.

Gove, M. K., and Benjamin, K. E. “Raising Pre-Service Teachers’ Cultural Antennas: Choosing and Using Quality Multicultural Literature.” Thinking Classroom , 7.2 (2006): 11–19.

Hinton, KaaVonia. “Trial and Error: A Framework for Teaching Multicultural Literature to Aspiring Teachers.” Multicultural Education 13.4 (2006): 51–54.

Hunt, Tiffany, and Bud Hunt. Learning by Teaching Multicultural Literature. English Journal , 94.3 (2005): 76–80.

Landt, Susan. M. Multicultural Literature and Young Adolescents: A Kaleidoscope of Opportunity. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 49.8 (2006): 690–697.

Langer, Judith A. (1994). A Response-Based Approach to Reading Literature. (ERIC Document Production Series No.ED366946).

Loh, Vu. Quantity and Quality: The Need for Culturally Authentic Trade Books in Asian American Young Adult Literature. The ALAN Review , 34.1 (2006): 36–53.

Louie, Belinda Y. Guiding Principles for Teaching Multicultural Literature. The Reading Teacher 59.5 (2006): 438–448.

Lowery, Ruth M., and Donna L. Sabis-Burns. “From Borders to Bridges: Making Cross-cultural Connections through Multicultural Literature.” Multicultural Education 14.4 (2007): 50–54.

Namioka, Lensey. Yang the Youngest and His Terrible Ear . New York: Yearling, 1994. Print.

Rogers, Theresa, and Anna O. Soter (1997). Reading across Cultures: Teaching Literature in a Diverse Society . New York: Teachers College Press.1997 Print.

Rosenblatt, Louise. Making Meaning with Texts . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2005. Print.

Simmons, John S., and Edward Deluzain. Teaching Literature in Middle as Secondary Grades . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. Print.

Stallworth, B. Joyce, Louel Gibbons, and Leigh Fauber. “‘It’s not on the list’: An Exploration of Teachers’ Perspectives on Using Multicultural Literature.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 49.6 (2006): 478–489.

Yang, Gene L. American Born Chinese . New York: First Second, 2006. Print.

Yang, Gene L. Gene Luen Yang . New York: First Second Books, n.d. Retrieved April 28, 2008, from http://www.firstsecondbooks.com/authors/geneYangBlogMain.html

Zygmunt-Fillwalk, Eva, and Patricia Clark. “Becoming Multicultural: Raising Awareness and Supporting Change in Teacher Education.” Childhood Education 83.5 (2007): 288–293.