ALAN v39n1 - The Verse Novel and the Question of Genre

The Verse Novel and the Question of Genre

The long poem for young readers is not a new phenomenon. Donelle Ruwe (2009) reminds us that book-length dramatic monologues were used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to present young readers with didactic stories, reflecting the belief that the physical action of recitation would reinforce the moral message (p. 219). The revival of the verse novel began tentatively in the 1990s with works for adults by writers such as Derek Walcott, Dorothy Porter, and Fred D’Aguiar, and for young adults at roughly the same time with novels by Virginia Euwer Wolff and Karen Hesse. The form for young adults has become an important publishing trend since the turn of this century. A quick look at one of the better Internet lists of verse novels for young adults—the one provided by the Edmonton, Alberta, public library ( http://www.epl.ca/ )—shows that of the 125 books in their holdings under that category, only five were published in the twentieth century. And as seems to be true in the smaller adult market for the verse novel, the young adult market features writers who have published more than one such novel. Karen Hesse, Ron Koertge, Allan Wolf, Margaret Wild, Angela Johnson, Ellen Hopkins, Nikki Grimes, Mel Glenn—each has more than one verse novel to his or her credit.

Many a verse novel advertises on the cover that it is “a novel by,” presumably because it would otherwise be misidentified by genre. This may be the publisher’s or author’s attempt to help the reader understand that there is a story here (and not “just verse”), or perhaps the writer and/or publisher fear that the potential reader will be intimidated by the format. The novel is still the most popular genre in the young adult literature market, and so by calling it “a novel,” publishers and authors reassure readers that this is what they’ve come to enjoy. Equally important, booksellers will shelve the book with other novels rather than with poetry, though my own experience is that the shelving process in bookstores and libraries is an inconsistent and idiosyncratic one across locations. Librarian Ed Sullivan (2003) notes that “The Library of Congress obviously cannot make up its mind whether these books are fiction or poetry, both, or neither” (p. 45).

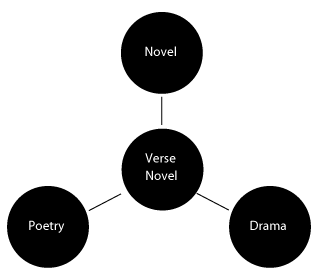

Those few who have written about the verse novel take the genre’s label at its word and just accept that the “problem” of the verse novel is about reconciling the poetic and prosaic. However, thinking of the verse novel solely in terms of either poetry or prose may be pursuing a false choice by insisting that the verse novel be one thing or the other. After a consideration of what is special (though hardly unique) about the voice of the verse novel, I offer some claims about the genre’s use of voice and its affinity to drama as a form; then I argue that we can learn a great deal about (and teach) the relationships among novel, poetry, and drama through an investigation of the qualities of the verse novel. Figure 1 offers a list of successful verse novels that could be valuable in your classroom.

Bingham, K. (2007). Shark Girl . Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press.

Block, F. (2006). Pysche in a Dress . New York: Joanna Cotler Books.

Bryant, J. (2006). Pieces of Georgia . New York: Knopf.

Creech, S. (2008). Hate That Cat . New York: Joanna Cotler Books.

Engle, M. (2010). The Firefly Letters . New York: Henry Holt.

Elliot, Z. (2008). Bird . Lee & Low Books.

Frost, H. (2003). Keesha’s House . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Grimes, N. (2002). Bronx Masquerade . New York: Dial Books.

Hopkins, E. (2008). Crank . New York: Simon Pulse.

McCormick, P. (2006). Sold . New York: Hyperion.

Rylant, C. (2006). Ludie’s Life . New York: Harcourt.

Schultz, S. (2010). You Are Not Here . New York: Push.

Sones. S. (2004). One of Those Hideous Books Where the Mother Dies . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Weatherford, C. (2008). Becoming Billie Holiday . Honesdale, PA: Wordsong.

Williams, C. (2010). Glimpse . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Figure 1. Other verse novels of note

Voice(s)

Ron Koertge’s Shakespeare Bats Cleanup (2003) features a character that writes in conventional poetic forms, but self-consciously. The protagonist asks, “Why am I writing down the middle / of the page? / It kind of looks like poetry, but no way / is it poetry. It’s just stuff” (p. 5). The protagonist, a teenaged baseball player sidelined by mononucleosis, has found a collection of poetry at home and is trying to write in different poetic forms. The narrative seems to be constructed in order to justify the use of poetic form and its variety in the novel, ultimately settling on what becomes a self-conscious use of free verse that distances the reader from the frame of mind that formal poetry inspires. At one point, our garroted first-baseman writes, “I gotta say, though, that the poems before / the free verse one were better in a way” (p. 79).

It is free verse that dominates the verse novel form, however, and it is usually not a self-conscious exercise for the narrator but something that we are to take as natural expression, just as we understand that characters in musicals are not “unnatural” for bursting into song on the street; we accept that what we are seeing is a convention that the characters are unselfconscious about as a form of expression and that elicits from the viewer an emotion and a way of thinking that is different from dialogue. Billy Jo from Out of the Dust ( Hesse, 1997 ) betrays no awareness of employing form or of writing verse. But beyond being an unselfconscious convention, there is a focus on the rhythms of the character’s spoken voice that does ask the reader to “hear” the speaker. It is enjambed prose written to emphasize a preferred pace and rhythm of speaking to the self. Joy Alexander (2005) makes the case that “free verse accentuates the oral dimension” (p. 270), and it is an opportunity to dictate for the reader where the speaker’s stresses and pauses reside. She goes on to argue, and I agree, that “The most prominent feature of the verse novel is voice” (p. 282). Who speaks, to whom, and where?

The voice of the verse novel is usually in the form of character narration rather than in the external narrative voice of the traditional long story poem or epic. The verse novel differs from Milton’s neo-epic or the voice of the Victorian long poem of Tennyson. Browning’s dramatic monologue is a close poetic parallel to the feel of the verse novel, for he provides us personal, natural voice and a sense of the scenic, but unlike Browning’s characters, the verse novel’s speakers do not tend to address directly within the poem a character “narratee”—or person addressed in the context of the poem. In Browning’s shorter dramatic monologues, such as “Fra Lippo Lippi,” “My Last Duchess,” and “Porphyria’s Lover,” as well as in The Ring and The Book , there is a strong sense of a narratee “in the room.” In a Browning poem, the reading audience can take on the narratee’s position, but Browning’s narrators are clearly speaking to someone in their presence. There is a pleading of a case, a rhetorical appeal, and the narratee is there being held by the elbow in the speaker’s time and place.

Joy Alexander (2005) claims that verse novels “are a modern means of rendering soliloquy or dramatic monologue” (p. 271), but she equates the two, and I believe they are different. The voice of the verse novel is still dramatic, but it usually employs the soliloquy in free verse form—even often when there are multiple voices at play in the story. As soliloquy tends to pull the speaker to the edge of the stage, perhaps as the background darkens, the verse novel tends to produce a similar feeling. The soliloquy is more of a self-address without regard for a listener: it muses. Consider this example from Karen Hesse’s Witness (2001):

i don’t know how miss Harvey

talked me into dancing in the fountain of youth .

i don’t know how she knew I danced at all.

unless once, a long time ago, my mama told her so.

but she did talk me into dancing.

i leaped and swept my way through the fountain of youth .

separated on the stage from all those limb-tight white girls. (p. 3)

The implied reader is no one and everyone. We can see Leanora Sutter during the first stanza—standing, arms folded, looking down, brow furrowed; in the second, she has arms akimbo, looking up, eyes bright, swaying at the memory. The prose form of diary or journal fiction is the most approximate reading experience. Overt uses of this form include Hesse’s Out of the Dust (1997), Koertge’s Shakespeare Bats Cleanup (2003), Jen Bryant’s Pieces of Georgia (2006), and Norma Fox Mazer’s What I Believe (2005). In the case of Out of the Dust , entries are headed by the month, day, and year. Mazer’s book is divided by titles like “Memo to myself” (p. 1). Journal or diary fiction often feels like a series of soliloquies. The verse novel doesn’t seem as interested in justifying the context of speaking as other novel forms do, however; in diary fiction, we have a “where” of the moment of speaking/ writing—the diary itself.

When there is a single speaker, we are provided a sense of characterization, but that character usually remains less than full and certainly less objectively rendered than we might get in a text with external narration, so the single-speaker verse novel usually builds a view seen through the eyes and heard from the voice of one, often-conflicted source. In this way, it is very much like other young adult character-narrated novels, despite its tendency toward soliloquy. After all, we have to decide about the character and even the reliability of young adult narrators—such as Holden Caulfield from Catcher in the Rye ( Salinger, 1951 ), Ponyboy Curtis from The Outsiders ( Hinton, 1967 ), T. J. Jones from Whale Talk ( Crutcher, 2001 ), Titus from Feed ( Anderson, 2002 ), and others—based on what they say or report others have said.

A more significant difference is when there is a cast of speakers who are presented from no particular perspective other than their own, and so reliability is much less of an issue, as in drama. The verse novel genre often features texts that are multiply narrated; these are often quite different than a YA novel told through either character or external narration. Verse novels with ensemble casts are not often stories that contain dialogue but rather alternating soliloquy. Neither do we typically get stories that offer conflicting and competing viewpoints. In verse novels, the multi-voiced ensemble cast is often designed to produce a full account often lacking with a single character narrator: dead relatives clear up family history in Allan Wolf’s Zane’s Trace ; townsfolk give a full account of Klan activities in Karen Hesse’s Witness ; the story of a thwarted school shooting is given a full account in Ron Koertge’s The Brimstone Journals (2001).

These ensemble casts are intersubjective. Rather than using a cast of characters that divide the duties of one protagonist, we are given the story through characters’ alternating soliloquy; verse novels seek to make a whole larger than the sum of its separate parts. As though we were watching the action on a stage, we see the spotlight move from one speaker to the next, and those characters’ respective soliloquies build a story that might well be acted out in dumb show behind them. The aesthetic of the polyphonic soliloquy novel is that it provides narrative wholeness through the fragmented and often unconnected soliloquies of different characters. For instance, Allan Wolf’s New Found Land (2004) alternates 14 distinct speakers over 400 pages, and in Terri Fields’s After the Death of Anna Gonzales (2002), there are 47 characters offering individually fragmented accounts that result in a collectively clear sense of story following a suicide.

Like traditional novels that are polyphonic, the first voice is usually reserved for the perceived central character—Despereaux’s voice comes before the rat’s or girl’s ( DeCamillo, 2003 ), Morning Girl’s comes before her brother’s ( Dorris, 1999 ), Stanley Yelnats’s comes first ( Sachar, 1998 ). Allan Wolf’s verse novel New Found Land gives voice to no minor character before Sacajawea, Oolum (Lewis’s Newfoundland alter ego), Lewis, Clark, and Jefferson; The Brimstone Journals begins with the voice of the kid who thwarts the shooting; Witness begins with Leonora, the African American girl at the center of the Klan story. Voice order is its own narrative logic in a novel with alternating voices, and that is certainly true for the verse novel.

Virginia E. Wolff has denied that her work is poetry ( Alexander, 2005 , p. 274), despite its layout on the page that suggests a free-verse arrangement that is mindful of the implications of voice through enjambment, as we see here in Make Lemonade (1993):

This word COLLEGE is in my house,

and you have to walk around it in the rooms

like furniture.

Here’s the actual conversation

way back when I’m in 5th grade

and my Mom didn’t even have her gray hairs yet. (p. 9)

Alexander (2005) reports that “Wolff consciously writes for the ear” (p. 274) and sees her work as manipulated prose; this might meant that it is best to consider her verse novels in terms of drama. Consider how drama is necessarily prose that is written for the ear (or tongue), making it a bridge between the orality of poetry and silence of novelistic prose. Consider that the verse novel Ann and Séamus (2003) by Kevin Major has been converted into a chamber opera with words and music by Stephen Hatfield. The verse novel lends itself, and has for centuries, to a physical, oral rendering, which adds the visual to the voice and provides what the genre of drama gives us.

Author backgrounds and creative contexts point to a strong relationship between drama and the verse novel. Consider that the 2008 Newbery-winner, Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! Voices from a Medieval Village (2007) by Laura Amy Schlitz, is written as a set of soliloquies that was used as a play in her Baltimore school. Allan Wolf spent years working with Poetry Alive! , a group that dramatizes poetry for live audiences; his first two novels are verse novels.

Verse, Novel, Drama

Voice is the most important signature feature of the verse novel, but there are other qualities and conventions that point to the genre of drama. Amy O’Neal (2004) says of the verse novel to “forget introductory paragraphs, transitional phrases, and summations. Just the facts; you draw your own conclusions” (p. 39). I think what we have in actuality are few facts rather than just the facts. What is missing is the exposition, the description, any external narration. What verse novels do is invite imaginative speculation about the things that are left unsaid by either characters or absent narrators—the descriptions of characters, settings, movements, and background information provided in the traditional prose novel that here are gaps, white or negative spaces, silences.

Wolf’s New Found Land is the exception that proves the rule: it allows characters to dwell on rich description of the journey (for instance, Sacagawea’s opening is a narration of her abduction, rich with description rather than just her feelings about it), but the novel requires 478 pages as a result, and it provides a character narrator in Oolum (the true name of Lewis’s dog) who behaves like an external narrator.

Consider Oolum’s opening dramatic monologue— a true dramatic monologue, as he is speaking to a narratee other than himself about the events of the journey: “I mean to tell you this story in the only way I know how. That is to say, I will tell it like a river. It may meander here and there, but in the end it will always find its way to the sea. […] And I am a seer. Though I cannot speak human languages, I understand them all, and on this journey there were many. But there is a universal language shared by all living things. It is called Roloje. Ro-LO-jee. You feel it in your heart. You see it when you sleep. It is spoken through the eyes and carried on the air but never heard. It is the language of longing. It is the language of anticipation and exploration, hopes and dreams. This is how I speak. This is how I am speaking to you now.” ( Wolf, 2004 , p. 8). Oolum’s sections are always in past tense (as opposed to most of the present tense of the book); interestingly, Sacagawea’s parts are always in present tense,. Most important, Oolum’s section is never in verse form; it stretches across the page between traditional margins. It is rich and fat.

In most other cases, however, we see how the white or negative space is the space in which description of setting and character is missing, and all of that blankness is pointed to as one element of the attractiveness of the verse novel to prospective readers. At one point, Kevin, the protagonist of Shakespeare Bats Cleanup (2003), provides some perspective on the issue of white space on the page as he reflects on his life had he never “found” poetry: “I wouldn’t know you like I do now. I would / have missed the way you pour down the / middle of the page like a river compared / to your pal, Prose, who takes up all / the room like a fat kid on the school bus” (p. 115).

The verse novel typically looks like any play or screenplay: it leaves a good deal of space on a page. In the printed form of drama, information of the scene’s appearance, character’s clothing, and other visual elements are often separate from the space of dialogue or monologue, if given at all. The verse novel leaves all of this description to the reader’s imagination, as when we read a play rather than see one. It is the work of the person staging the drama to make those visual decisions, and that same task belongs to the reader of a verse novel. The person reading is put in the role of a play’s director.

What the verse novel provides are the character’s words. When we have actual dialogue rather than soliloquy, the look of the play on paper is even more striking. Consider this from Allan Wolf’s Zane’s Trace (2007):

She: That’s too bad.

Me: What?

She: These door locks. They’re all electric.

Me: I like `em.

She: Once you start dating, you’ll know what I mean. (p. 41).

We might well be reading a play, and Wolf is arguably left little choice but to label the speakers in this way as a result of the lack of narration and description to provide the necessary information about who is speaking.

The verse novel often resorts to listing in the peritext—the apparatus outside of the narrative itself—those things that can’t be easily provided in a text bereft of description or external narration, just as playwrights provide their own peritextual apparatus in print form, whether in the written play or in the notes provided the audience at a performance. Allan Wolf’s Zane’s Trace begins with a list of “Dramatis Personae” containing each character’s name and description: “Zane Harold Guesswind: A seventeen-year-old boy driving a stolen 1969 Plymouth Barracuda.” We are given the settings for the entire story: “A tangle of highways and back roads from Baltimore, Maryland, to Zanesville, Ohio. A diner. Two McDonald’s drivethrough windows. Two graveyards. A motel. And a funeral home.” The names and descriptions of the Corps of Discovery come before the journey begins in Wolf’s New Found Land . Ron Koertge’s Brimstone Journals begins with a page listing all of the names of the characters in a unique cursive form. Karen Hesse’s Witness leads with a character page on which the names, ages, and pictures of the eleven speakers are presented. The polyphonic verse novel is strongly presented as drama. Ironically, the book with “Shakespeare” in the title has the least dramatic quality of the books I discuss here.

Two polyphonic verse novels—Karen Hesse’s Witness and Ron Koertge’s The Brimstone Journals — are written in five parts, and it’s easy to see that they follow a five-act play’s structure: set up, rising action, crisis and confrontation, climax, and conclusion. Nothing marks this structure but the use of numbers separating sections. In their discussion of The 2005 Lion and the Unicorn Award for Excellence in North American Poetry, Richard Flynn, Kelly Hager, and Joseph T. Thomas (2005) note that “the poet who chooses this form fashions an over-arching narrative, making explicit the links between the individual poems and foregrounding the teleological structure of the whole” (p. 429), which implies a five-act structure that helps the reader consider the relationship between those individual poems in any “act.”

Campbell (2004) argues that “the structure of a verse novel […] can be quite different from the novel, which is built with rising conflict toward a climax, followed by a denouement. The verse novel is often more like a wheel, with the hub a compelling emotional event, and the narration referring to this event like the spokes” (p. 615). We can see this analogy in a book like Hesse’s Witness , in which a murder is the central event to which all character soliloquies refer, or Koertge’s The Brimstone Journals , in which it is the thwarting of a shooting that is the event to which all voices refer. This describes the way that the individual soliloquies or dialogue provide an unmediated narrative that collectively fleshes out the story.

I would contend that even the loosest verse novel has a conflict that is resolved over the course of the book, just as diary and epistolary fiction manage what life often doesn’t provide—a plot. Even in those verse novels unmarked by act, one sees that the immediate juxtapositions that seem random have, from a distance and a handful of monologues at a time, forged the causal chain that creates story rather than simple narration. It’s rather like one of those picture mosaics that create from individual and unrelated pictures a larger image. I might go so far as to call some of these “mosaic novels.”

One last parallel to the experience of drama is also a reception issue. Though many of these verse novels are well over 100 pages—and many are much longer—there are few that can’t be read in one sitting. This “single effect” is the same experience that drama and short fiction provide, the lack of which Poe believed was a serious detriment to long prose fiction. The verse novel, like drama, privileges the aesthetic of experiencing story in one sitting.

Implications

Figure 2. Verse novels demonstrate the interplay of genres.

That the verse novel form has such strong associations to three distinct genres strikes me as an opportunity for students to learn more about the novel, poetry, and drama in relation to each other instead of as separate and unrelated forms. Instead of worrying about which of two genres the verse novel is most like, possibly creating a version of genre tug of war, we should use the form as a gateway to three genres in the nexus that it forms between them all (see Fig. 2). In fact, the verse novel could be the touchstone text for transitions among units on the novel, poetry, and drama. While the gap between the novel form and poetry might seem great, and the forms discrete and autonomous, the use of various short forms of narrative poetry, followed by the epic, and then the free-verse novel provide three points of transition along a continuum from lyric poetry to the novel. In that transition, students will see the subtle changes in form rather than two completely unrelated literary genres. The consideration of each of the three genres of novel, drama, and poetry in terms of one of the others is facilitated by the verse novel as transitional text.

In its place between poetry and drama, the verse novel employs the lyricism and rhythm of poetry with the voice of the spoken word emphasized in drama. In its place between drama and the novel, the verse novel combines the sustained development of the long prose form with the description-free, character-rich nature of the written play. Perry Nodelman (1991) notes that picturebooks for children are theatrical forms of prose that provide the images in picture form rather than written description; so, too, the verse novel forces the reader to plug in the stage images left undescribed in print. In all cases of serving as a nexus among the three genres, the verse novel combines the most complementary aspects of those forms. In fact, the verse novel may well be a playwright’s best option for reaching an audience in the young adult fiction market.

Studying the verse novel will build in students an appreciation for other blends and crossovers so common in contemporary literature, such as multimedia texts, multigenre texts, intertextuality, and cross-audience texts. We tend to want to present literature as divisions of genres and modes with their own separate Figure 2. Verse novels demonstrate the interplay of conventions rather than as a set of relationships in and across time. The verse novel seems to be a form demanded by our age, and contemporary young readers seem to acknowledge its timeliness.

The verse novel is so successful in large part because it is so readable. Rather than bemoaning its failure to be one thing or another—thus making it out to be some sort of monstrous and insufficient form—we should be celebrating its rich combination of generic strengths, its melding of the most engaging aspects of three genres to create a very appealing form. We have the sustained story typical of the novel, the guided pace provided by free verse’s use of enjambment, and the dialogue-rich nature of drama. What the verse novel lacks in description and extended narration, it makes up for in its insistence that the reader provide those things on his or her own, both demanding and enabling the reader to imagine appropriate and personally satisfying images that match the context of the soliloquy and/or dialogue-driven narrative. By using the verse novel as touchstone text to learn more about three distinct genres, we would be learning how the verse novel itself is its own thing rather than a failed version of something else.

Mike Cadden is a professor of English and chair of the department of English, Foreign Languages, and Journalism at Missouri Western State University where he teaches children’s and young adult literature. He is the author of Ursula K. Le Guin beyond Genre (Routledge) and recently edited Telling Children’s Stories: Narrative Theory and Children’s Literature (Nebraska University Press).

Works Cited

Alexander, J. (2005). The verse-novel: A new genre. Children’s Literature in Education, 36, 269–283.

Anderson, M. (2002). Feed. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Bryant, J. (2006). Pieces of Georgia. New York: Yearling.

Campbell, P. (2004). The sand in the oyster: Vetting the verse novel. Horn Book Magazine, 80, 611–616.

Crutcher, C. (2001). Whale talk. New York: HarperCollins.

DiCamillo. K. (2003). The tale of Despereaux. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Dorris, M. (1999). Morning girl. New York: Hyperion.

Fields. T. (2002). After the death of Anna Gonzales. New York: Henry Holt.

Flynn, R., Hager, K., & Thomas, J. (2005). It could be verse: The 2005 lion and the unicorn award for excellence in North American poetry. Lion & the Unicorn, 29, 427–441.

Hesse, K. (1997). Out of the dust. New York: Scholastic.

Hesse, K. (2001). Witness. New York: Scholastic.

Hinton, S. (1967). The outsiders. New York: Viking Press.

Koertge, R. (2001). The brimstone journals. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Koertge, R. (2003). Shakespeare bats cleanup. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Major, K. (2003). Ann and Séamus. Toronto, ON: Groundwood.

Mazer. N. (2005). What I believe. New York: Harcourt.

Nodelman, P. (1991). The eye and the I: Identification and first-person narratives in picture books. Children’s Literature, 19 ,1–30.

O’Neal, A. (2004). Calling it verse doesn’t make it poetry. Young Adult Library Services, 2 (2),39–40.

Ruwe, D. (2009). Dramatic monologues and the novel-in-verse: Adelaide O’Keeffe and the development of the theatrical children’s poetry in the long eighteenth century. The Lion and the Unicorn, 33 , 219–34.

Sachar, L. (1998). Holes. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux.

Salinger, J. D. (1951). The catcher in the rye. New York: Little, Brown.

Schlitz, L. (2007). Good Masters! Sweet Ladies! Voices from a Medieval Village. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Sullivan, E. (2003). Fiction or poetry? School Library Journal, 49 (8), 44–45.

Wolf, A. (2004). New found land: Lewis and Clark’s voyage of discovery. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Wolf, A. (2007). Zane’s trace. Somerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Wolff, V. (1993). Make lemonade. New York: Henry Holt.