Graphic Novels, Adolescence, “Making Spaces,” and Teacher Prep in a Graduate YAL Course

Political and intellectual forces are exerting pressures that may challenge the ecology—the space, place, and landscape—of Young Adult Literature (YAL) in English language arts teacher education curricula and in K–12 classrooms. A call for the January 2015 issue of English Journal , for example, asks stakeholders to consider what the authors call the “youth lens,” one that can “sit alongside feminist, queer, Marxist, and postcolonial approaches” and “views adolescence as a construct and calls attention to and critiques representations of youth” ( NCTE, 2014 ). The call suggests a narrow contemporary view of adolescence that may guide future constructs of adolescence and YAL courses:

[W]e have yet to sufficiently examine how we view adolescence and how these views affect how we teach English. Typical ways of thinking about adolescence come from biological and psychological understandings (e.g., raging hormones, identity crisis). These lenses prevail in our thinking, representing the adolescent as a moody, self-centered, peer-oriented being that is different from adults in distinct ways. These deficit orientations position youth passively, present their life circumstances as demeaning, and fail to account for seeing this category, like others, as a social construct.

How, then, will challenging our notions of adolescence influence our construction of YAL and its courses? What are the ramifications for accepting “deficit orientations,” if the call is accurate in its claim?

Forces at Play or Forces at Bay?

In “‘We Brought It upon Ourselves’: University-Based Teacher Education and the Emergence of Boot-Camp- Style Routes to Teacher Certification,” Friedrich ( 2014 ) also takes issue with education’s over-reliance on psychology-based notions of learning and development, seeing it as a reason why education programs are undermined by alternative routes to teacher certification. The “psy-field” lens has led to detrimental decisions driving methods, content, and curricula, “colonizing” teacher education, and “serving as the privileged lens through which content and learners are being led” (p. 5).

Rather than view child and adolescent psychology as representing absolutes, Friedrich suggests teacher educators observe the “psy-field” as one of many lenses needing examination, historicization, and contextualization within methods and content, which, Friedrich argues, are too often separated in current teacher education programs. YAL courses, often but not always housed in English departments, have been under scrutiny since they’ve existed, from without and within: Should they be literature courses and focus only through literary lenses? Should they be methods courses or hybrids? Friedrich’s concerns could offer support for blended approaches to YAL curricula, not to mention graduate-level YAL courses. The field has long been discussing ways to develop and offer such courses with appropriate curricular fit and rigor.

Furthermore, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010 ), with their oft-confusing and contradictory statements on exemplars, new ratios for fiction–nonfiction, and new definitions of American literature, world literature , and informational texts , may affect drastically the choices teacher educators make in YAL courses as they scramble to meet state-mandated edicts while keeping true to their own expertise. How many are changing their syllabi in response, making room for nonfiction or replacing salient YA texts with those favored by the politically powerful proponents of CCSS? Indeed, even our professional journals’ editors feel compelled to address the CCSS and the tensions they create for YAL (keep reading this issue of TAR and see Fall 2013’s nonfiction focus, for example). In addition, if secondary teachers are forced into constricting curricula that represents a re-reification of the canon, what role will YAL play in students’ development in school spaces, and how might that affect the perceived need for YAL courses in ELA teacher preparation programs?

Ecology, Erudition, and Experience in “Literature for Youth”

In autumn of 2012, I spearheaded the initial offering of a graduate-level YAL course in which I and my students presciently (read “unwittingly”) addressed issues of curricula and purpose mentioned by Friedrich and, eventually, in the aforementioned English Journal call. We crafted a possible blueprint for a graduatelevel YAL course and overtly challenged the underlying assumptions about textual complexity, quality, and learning inherent in the misguided CCSS. Herein I offer details about the course and how my students and I explicitly examined the need for YAL that blends literary and social science lenses in the ecology of teacher education and K–12 settings.

About the Course

English 5340 “Literature for Youth” is a graduatelevel course for students in the University of Texas at El Paso English Department’s recently revived MAT degree. The course serves both experienced K–12 ELA teachers seeking an advanced credential and many recently graduated students with no teaching experience beyond student teaching. My syllabus’s description of the course reveals its goals, very much reminiscent of those in the EJ call and Friedrich’s article:

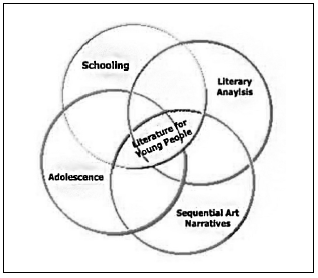

The Venn diagram in Figure 1, sitting atop the syllabus, attempted to visualize for students how our various components would intersect.

In her “Strengthen the Profession” chapter of Reign of Error , Diane Ravitch ( 2013 ) argues that while in teacher education programs, students should:

Figure 1.

A visual representation of the curricula for “Literature for Youth”

Here Ravitch does not run counter to Friedrich, who calls for the “psy-focus” to be considered a lens, not the lens . As English 5340 developed, my students illustrated for me that college-level Young Adult Literature courses, depending on how they are framed, are potential spaces, possible ecologies, where future teachers examine many of these subjects. That every YAL text we read was a comic or graphic novel, while not the focus of this essay, suggests that format and genre are still important concerns when developing YAL courses, but they needn’t be the primary ones. (Nobis [ 2013 ] recently wrote, “I don’t understand why we still so often have to debate the merits of graphic novels” [p. 31], and I have abandoned the apologetic stance that demands a constant recapitulation of defining them then defending them. That work has been done and is readily available. A good place to start would be this essay’s bibliography.) Below, I discuss inspirations, goals, and resources from the course and share student responses supporting my claim.

Curricular Inspirations and Integrations

In planning the course, I drew upon my scholarly influences regarding young adult literature, namely Donelson and Nilsen, whose Literature for Today’s Young Adults ( 2005 ; see also Nilsen, Blasingame, Nilsen, & Donelson, 2012 ) has been a staple in how I situate students’ earliest framings of YAL, especially in terms of how to define and analyze such texts for quality and how to view them through allegorical lenses. I am also influenced by Kaywell ( 1997 , 2000 , 2010 ) and others ( Lesesne, 2010 ; Herz & Gallo, 2005 ) who promote a complementary approach to integrating YAL into secondary classrooms. I find such an approach gels nicely with my aim of asking teachers to organize their instruction thematically or around big questions ( Smagorinsky, 2008 ; Stern, 1995 ).

My own work informed my decision to integrate comics as the main texts, as I have found (as did Lapp, Wolsey, Fisher, & Frey, 2011/2012 ) that many educators aren’t using comics and may be unaware of the medium’s potential, despite available scholarship ( Bakis, 2012 ; Bitz, 2009 , 2010 ; Carter, 2007a , 2007b , 2012 ; Jacobs, 2007b ; Monnin, 2009 , 2013 ; Seglem, Witte, & Beemer, 2012 ; Schwarz, 2002 ). By asking students to read texts that qualified as YAL and comics, I hoped to enhance their knowledge of both. Through exploring the comics’ young characters as exemplars of adolescent experiences in life and especially in school, I hoped to tap into the power of multiple-case sampling in order to, as Miles and Huberman ( 1994 ) suggest it should, “add confidence” to our findings as texts and conversations multiplied. As students moved across our seven general themes (see below), they were able to note nuances, but also to triangulate ( Stake, 1995 ; Yin, 2008 ) similarities between textbook case studies, various adolescents’ actual and fictional experiences, and scholars’ opinions on facilitating successful schooling experiences for young people.

The second edition of Michael Sadowksi’s edited collection Adolescents at School ( 2010 ) 1 braided together the strands and provided further critical framing and research. Sadowski often mentions Erikson’s theories of adolescent development ( 1968 ), and so too did our work in using young adult graphica to study “aspects of identity that can have profound effects on adolescents’ learning and school lives: race, ethnicity, immigrant status, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, social class, ability and disability, and spirituality” (p. 5). Indeed, beyond the initial frames provided by Donelson and Nilsen, the concepts of developmental moratorium and foreclosure (see Sadowski, p. 15 ) were among the first and most common through which students viewed characters. Both Sadowski and Donelson and Nilsen assert that the guiding question of young adults and young adult literature is “Who am I?” ( Sadowski, p. 13 ). Donelson and Nilsen add Patty Campbell’s line, “And what am I going to do about it?” (p. 3).

Furthermore, while all texts are multimodal ( Kress in Cope & Kalantzis, 2000, p. 187 ), I contend that comics are more multimodal than most (Groensteen, 2007 , 2013 ; Jacobs, 2007a , 2013 ; Wolfe & Kleijwegt, 2012 ). I set a goal for these students to consider expanded visions of adolescents, schooling, and textuality to engage in what the New London Group calls “transformative practice” when they return to their classrooms. I wanted my students to be more informed regarding what it means to be an adolescent in contemporary American schooling; to note what tensions teenagers experience as they navigate and construct identities and differences and influence and are influenced in social spheres; to acknowledge comics’ ability to facilitate literary, interpersonal, and intrapersonal connections within the classroom; and to consider how, as teachers, they might open, create, or facilitate spaces for students once they apply their new knowledge.

To meet those objectives, we studied chapters from the Sadowski text, along with other articles from education scholars and literary-based comics scholars, as well as roughly 25 graphic novels through six overlapping, reciprocal, and reflexive “identity themes”: Youth and the Middle East; Racial Identity and Immigration; “Latinidad” and Chicano/a Identity; Gender; Sexuality and Faith; and “Disability.” Students furthered their individual interests by crafting a 30-source bibliography and 20-page research paper themed “Adolescence and [A Topic of Their Choosing].” In addition, we each posted several weekly entries devoted to our readings to a DelphiForum message board. We shared thousands of words over 982 messages. The forum became a prime learning space for us, and students were quick to relate that just as I and our authors were asking them to consider opening up spaces for adolescents who might not see themselves reflected or accepted in literature or in their school settings, I had “practiced what I preached” by creating a (multimodal) online space for open, frank discussion and sharing.

The class was comprised of 26 students—7 males and 19 females. The class was diverse, including individuals who identified as Black, White, Hispanic, Native American, and Asian American. Several identified as “mixed” at times, but as one race or ethnicity at others. They also identified as either straight or gay. Twelve identified as having previous or current teaching experience.

After initial introductions to the course, basic “best of the best” tenets and themes of YAL, an overview of the Sadowski text, and a crash course in the scholarship on comics and literacy, students were asked to share what made them excited and anxious.1 Many noted the course’s focus on graphic novels:

Adri: When I found out that the class was going to cover graphic novels, I was excited. I spent many years reading manga and comic books, and I knew graphic novels could be useful in a classroom setting, but I wasn’t too familiar with them. I’m hoping to see and better understand the effect that graphic novels can have on society, particularly our young ones, who cringe at a book with thousands of words, but who instantly become interested when there are pictures involved.

Maria-Rebecca: The first day of class really helped tie all sorts of loose ends that the syllabus had left. I am very interested in learning more about how young adult literature in combination with adult guidance can aid adolescents in developing an identity. I was surprised to learn that the coming of age theme was essential to young adult literature. I very much enjoy reading classic novels that treat the bildungsroman theme and am fond of using this type of reading as core or supplemental texts in lesson planning. I am most interested in exploring the graphic novel as a medium and learning how to incorporate them into my future classroom.

Nadia: I am concerned about the number of graphic novels that we have to read since I have never read one before and I am not sure what to look for and analyze in them. I believe once we start posting our ideas and responding to each other, all my worries will be put to rest.

Brenda: Like Nadia, I’ve only read one graphic novel ( Maus [ Spiegelman, 1986 ]), so I’m very excited about reading the variety of novels we have for this class. I like the idea of a Literature for Youth class actually using the books that young adults read. I am also looking forward to researching my topic and learning something new.

Rebecca: I am extremely excited about working with and reading all the graphic novels this semester because they are a medium which I have not had too much experience using as a teaching tool.

Ashleigh: I am most excited about the variety of graphic novels we will be reading, particularly the variety of races and experiences the texts will expose to us to as readers. Experiencing a life different than your own through text is one of the best qualities of literature, and I believe it is even more enhanced in the graphic novel art form. Beyond the reader-text experience, the novels will help me to better understand the diverse populations of students I will teach.

Joshua: I’m very interested in engaging in a new literary medium. This is my first opportunity to study the graphic novel in a classroom setting and I’m pretty excited to doing so. As an English and American Literature undergraduate, I spent my entire college career reading novels from the “canon of classic literature.” I have very little personal experience in reading graphic novels, having only read Maus and a graphic novel interpretation of Moby Dick.

This data suggest that, early on, the class allowed several students to consider the graphic novel as schoolworthy text for the first time. Especially, they appear intrigued at the “novelty” of comics in the classroom. A common rejoinder was for students to discuss anecdotes of interest or even confusion from peers or family regarding why “comic books” were appropriate space for graduate students, much less teens. Consider Ana’s commentary from our first identity unit, “Youth and the Middle East”:

Such responses ebbed from the message boards as students read more graphic novels, suggesting the very sensible possibility that if more teachers read more graphic novels, they might be more willing to open up space for them in their classrooms.

Our second identity theme was “Racial Identity & Immigration.” Given the diversity of the participants and the fact that the course took place less than a mile from the US/Mexican border (border identity dynamics are often at play in my students’ classes), it is worthy of special attention. Brandon makes clear connections between several of the graphic novels, including Anya’s Ghost ( Brosgol, 2011 ) and American Born Chinese ( Yang, 2006 ), in this unit and issues from the Sadowski:

Anya, Jin, and Danny all face this idea of conflicting worlds throughout the graphic novels. Anya has put in her time adjusting to the American way of life and still feels the separation of her American lifestyle from the Russian lifestyle she lives with at home. She initially denies friendship with Dima because of these ideals of separation between her American and Russian characteristics. Jin attempts to deny friendship with Wei- Chen because of these same ideals related to the work he has put into becoming American. Danny faces this split in worlds as he battles his feelings against his cousin, Chin-Kee. Danny is the “true” American high school teenager, but is constantly reminded of his past by the annual haunting of his exuberant cousin.

The Sadowski chapter says, “For immigrant youth, how they negotiate different and often conflicting expectations plays an important role in their adaptation and development, both during adolescence and beyond,” and this is seen throughout both graphic novels as each teenager attempts to create a personal identity ( Suarez-Orozco, Qin, & Amthor, 2010, p. 55 ). The majority of the characters in these two graphic novels seem to be partaking in what the authors calls “Relational engagement,” which is “the extent to which students feel connected to their teachers, peers, and others at school” (p. 62). “Social relations provide a variety of protective functions—a sense of belonging, emotional support, tangible assistance and information, guidance, role modeling, and positive feedback” (p. 62). The relationships that each of the characters build reflect what they are trying to create themselves into. Jin wants to become American in order to date Amelia; Anya wants to become American until she realizes the horror that Emily reveals to her; Danny wants to dismiss his Asian heritage because of the way Chin-Kee represents himself. All of the characters are interrelated, and most form some sort of relationship in order to produce their own identity.

Lisa, one of our veteran teachers (a literacy specialist) who became a role model for many peers in the course, makes practical applications:

One way to close the gap is for teachers to provide opportunities for immigrant students to learn to adapt to cultural changes while providing classroom situations in which native students learn about the different cultures and customs that their new classmates bring from home. These ideas call for graphic novels such as American Born Chinese and The Arrival [ Tan, 2006 ]—the first one because it speaks to the stereotypes that many immigrant students face while at school, and the second one because it depicts the plight of the immigrant en route to a “better life.”

The exposure of all the experiences shared in the narratives of these graphic novels supports the profound shifts that newcomer immigrant youth undergo as they struggle with who they are and the changing circumstances they are negotiating in relationships with their parents and peers ( Suarez-Orozc, Qin, & Amthor, 2010, p. 63 ). Addressing stereotypes in this manner would provide all students with an opportunity to experience an immigrant’s challenges, fears, and hopes while fostering an environment of understanding and acceptance in the classroom for all.

Therefore, as Lee reminds us in “Model Minorities and Perpetual Foreigners”:

Bernie, another experienced educator, responds:

“The first step in this challenge is the teacher’s willingness to be aware of her students’ backgrounds and, thus, to make instructional decisions to include multicultural literature that mirrors the ethnic diversity in her classroom. Yes, there is no place like home . . . welcome to room 222 where your home has a place of honor. Please come in.”

This line reminded me of a student I had about three years ago. He was a Korean boy named Jae, but he insisted on spelling it as Jay. I guess he wanted to Americanize his name because he said Jae was too difficult for teachers to remember how to spell. I never gave in to that spelling of his name. I remember one time, I was asking about his schooling back in Korea. I was curious as to how it was different from American schooling. He explained to me how students were studious and parents were very strict about their children achieving success in school. But then he said something like, “But that was in the past. I don’t want to talk about it because it’s embarrassing.” I stopped him right there and told him he should never be embarrassed about where he came from. He was Korean and that was part of him, his identity. I told him to be proud of everything that led him to be what he was.

Jae had lived in Mexico before coming to El Paso, and he was fluent in Spanish. He had also learned English while in Mexico because he had attended an American school over there. He was in my AP English I class and had the highest grade, not because he was the smartest, but because he was the hardest working student I had ever known. If he didn’t understand something, he would ask 100 questions until he did understand. He would come before and after school and even during lunch to get help if he needed it. This was not just with me, but with all his teachers. Even though he came to M.H.S. three weeks late, he kept up with the current work and made up the three weeks he missed before the end of the quarter.

My point here is that even though I saw evidence of Jae trying to “distance” himself “from the stigma of foreignness,” he kept true to his upbringing in regards to education. He was not about to let himself drop below a 98% in any class ( Lee, 2010, p. 78 ). But I hope it was also in part because the teachers provided him with a safe environment, and his “relational engagement” was pretty high, including at home with his mother. Although his father was away on business much of the time, his mother seemed to have a big role in his life. She was his guiding force. He also had Korean friends outside of school. Because Jae had an emotional support network, he did live up to the model immigrant stereotype.

Jin of American Born Chinese seems the exact opposite of Jae. It seems the “relational engagement” that Suarez-Orozco, Qin, and Amthor ( 2010 ) write of was perhaps lacking in Jin (p. 62). There is hardly any mention of his parents, his teachers get his name wrong, his American peers make fun of him, and he doesn’t care to associate with those of his own country. He seems pretty isolated, and so the “sense of belonging, emotional support, tangible assistance and information, guidance, role modeling, and positive feedback” are virtually lacking in his life (p. 62). Jin seeks to fill this void with as much assimilation into American culture as possible. He seeks out emotional support from Amelia, and the only way he can get that, he thinks, is by shedding his true identity.

Lisa and Bernie are exploring connections to classroom practice and realities that relate to what they noticed in the research and the “case studies.” Sadowski and his contributors often offer student biographies or situations as cases, too—yet another example of how my case approach matched well with Adolescents at School .

As we moved through other identity units, students repeatedly expressed one desired point of action—the need for teachers to facilitate spaces for adolescents to be themselves, regardless of or in some cases specifically based on their gender, sexuality, immigrant status, etc. This type of transformative practice among teachers is a key objective of the Sadowski text, but he worries that . . .

Josh articulates his interpretation of tensions between policies and practice:

The challenge then becomes how are teachers able to do this in an environment that seems more focused on standardized testing than on the individual student? How can educators foster this open space where a wide range of topics can be covered when they are challenged to prepare “most” students to pass a test?

Certainly NCLB, the Common Core, and the privatization movement, often cloaked in the rhetoric of academic improvement for all children, suggest a future for adolescents where sense of achievement will be connected almost solely to standardized testing, as may be their teachers’ and administrators’ jobs. In such boiler room environments, will teachers be able to facilitate spaces that weren’t necessarily always present in the pre-Common Core classroom, either? Many of my students were left with an “If not me, who?” ethos regarding creating in-class environments where all students felt represented, valued and valid. But, as Miles Myers ( 1996 ) forewarned, perhaps these spaces can’t exist in school except as before- or after-school programs and clubs. I attest that thematic instruction or inquiry units may be one means of opening up dialogue with adolescents and that YA graphic novels can help students build connections between and among peers in ways that might facilitate acceptance and understanding.

However, we know that despite the benefits of thematic approaches, many teachers continue to teach using traditional modes. We have evidence that despite research on the benefits of YAL ( Hazlet, Johnson, & Hayne, 2009 ; Rybakova, Piotrowski, & Harper, 2013 ) and graphic novels, teachers aren’t incorporating such texts as much as they ought, nor are they maximizing their potentials. And when David Coleman, a major player in the construction of the English Language Arts Common Core State Standards, seems to support the notion that texts that build connective tissue between students’ identities and lived experiences need to take a back seat to informational texts and rhetorical writing because “[a]s you grow up in this world you realize people really don’t give a shit about what you feel or what you think,” 2 how far can “If not us, who?” take an educator, especially a beginning teacher, in meeting Sadowksi and his contributors’ ultimate goal?: “If we want all students to achieve—not just on tests but in the pursuits that are important in their own lives—then trying to understand as best we can who they are and where they are coming from may be the best place to start” ( Sadowski, p. 8 ).

The Ecology of Claims

I cannot say with certainty that all of my students are now more likely to integrate comics into their future classrooms, nor can I offer hard evidence that they will be successful at attempts to open up spaces for acceptance for all manner of adolescents struggling and striving to define themselves at crucial social and intrapersonal moments in their lives. Further, I can’t offer evidence that those not teaching thematically or via guiding questions bought in to that approach. What I can offer is that my students did learn from the case approach in terms of making connections between academic scholarship, central characters from the comics, and the educational researchers’ work. Furthermore, and perhaps of greater consequence to readers herein, many expressed a wish that they had been exposed to the adolescent identity research much earlier in their teacher education courses than the graduate level:

Bernie : I was just wondering how you all felt as teachers going into the classroom. Did you feel your education classes had adequately prepared you for dealing with adolescent issues in the classroom? On p. 222, John Raible and Sonia Nieto (in Sadowski, 2010 ) show how researcher Laurie Olsen “found that the great majority of teachers did not believe that they needed additional preparation to serve the new diversity at the school. Most reported that being ‘color blind’ was enough.” I wonder why this is? Is there something wrong in the way teachers are prepared, or should I say, unprepared, for dealing with the realities of a classroom? . . . [N]ot until my graduate classes was student identity ever stressed as an important pedagogical step in the classroom. When I applied lessons in my own class that have students reflect on their identity, I saw the need in their lives for such discussion in the way they responded to the assignment, whether it was in writing or in a classroom conversation.

Amy frames her comments in relation to the “Racial Identity & Immigration” theme:

Other students speak more generally, but mention the course as a possible motivator of transformed practice:

Cathy: Like Bernie, I felt that my preparation going into teaching could have been better established through the courses I enrolled in and partook. I have a good understanding of what is required from me, but working under a teacher as an intern for 15 weeks is not the same as being the teacher. My responsibility as an intern was to grade papers and make copies. . . .

Maria-Rebecca: To be honest, I did not feel that my education classes adequately prepared me for dealing with adolescent issues . . . . Like Bernie, it was not until my graduate classes that student identity was stressed as an important pedagogical step in the classroom.

Carissa: The classes that I have taken at the undergraduate level did not at all prepare me for teaching. In fact, I thought they helped me to realize that I was not ready to be the kind of teacher that I wanted, therefore I continued on with my education and enrolled in graduate school. Although I am only finishing up my first semester, I feel like I have learned more in a semester than I did in four years!

Emily:

I would argue that the education classes which

I took prior to my internship did not provide as

much preparedness as this graduate course has as

far as instilling an explicit awareness of the many

dimensions which students are navigating within.

The only teaching experience which I possess is

the four months I spent interning in a sophomore

English class during the spring of 2012. During this

period, I learned an extraordinary amount about

classroom management and student interactions

which could only have been learned by physically

being in the classroom with 30 very unique

individuals, staring at

me six periods a day.

However, I do wish that

I could have known

more about identity and

its enormous effect on

adolescents because

I would have been

a better teacher. Of

course I was aware that

students were dealing

with personal problems

regarding sexuality,

disability, immigration,

and even suicide; however,

it is only through

Adolescents at School

that I have learned the scope

and magnitude of adolescent identity and ways to

incorporate it into the classroom curriculum.

One of the most long-lasting lessons which

I will take away from this text as a novice teacher

is the necessity to create welcoming, safe spaces

for dialogue where students can express themselves

without fear of chastisement. These spaces

will lead to improved learning because students,

ideally, will be able to focus more on their studies

than on their preoccupations. Secondly, I have

learned the power of being a teacher advocate. A

running theme through this text has been students

relaying horror and success stories of teachers’ actions

within their education. As an educator, I need

to aggressively advocate for my students so that my

classroom becomes a safe space, absent of intolerance

and deficit perspective, so that my students

may engage and receive the best education possible.

While many Young Adult Literature courses serve future ELA teachers, there is debate about whether they are best taught as literature courses or as methods courses, or as hybrids. Friedrich and others may suggest that a multi-lensed approach best serves the field and teacher education students. Furthermore, CCSS may necessitate such hybrids. (Scholarly articles are high-level nonfiction texts in and of themselves, after all, suggesting that YAL courses can keep the salient texts and address new foci on other text forms.)

Conclusion: YAL as Essential, Ecological Sweet Tooth(?)

My ENGL 5340 students suggest studying YAL alongside research about adolescence and schooling, braided with talk of methods, and facilitated by understandings of adolescent identity and needed school ecologies. Through the texts and cases studied, students in the course saw the importance of teaching beyond tests and standards, be they Common Core State Standards, Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness. They glimpsed the great need for teachers to understand not just YAL, but adolescents and how to use YA literature to facilitate enriching learning situations with teens that consider the self—the multiple selves, even—with informed, accepting teachers who do indeed give a shit what they think and feel and experience. My students gained a glimmer of cognizance that for preteens and teens, that is at the core of education; it is where we must seek transformative practice for preservice teachers, practicing educators, and their students. That we may have precognitively addressed growing concerns about the space, place, and landscape of YAL courses and curricula at the undergraduate and graduate levels and thereby offered possible solutions to our colleagues as they navigate new pressures and mandates? Well, that’s just cake.

Notes

1

To see a table of contents to help with references to specific

chapters and contributors herein, visit

http://www.lib.muohio.edu/multifacet/record/mu3ugb3971413

.

2

To hear these words and get a feel of their context, visit

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pu6lin88YXU

.

Dr. Carter is a visiting assistant professor of English Education at Washington State University, Pullman. He studies YA Lit, multimodality, and comics-and-literacy connections and has published books, articles, and chapters on that topic. Currently, his interests include facilitating interdisciplinary conversation among academics studying graphica from disparate angles, comics and culturally relevant pedagogy, and representations of the American Southwest and Borderland in comics and graphic novels.

References

Amir & Khalil. (2011) Zahra’s paradise. New York, NY: First Second.

Bakis, M. (2012). The graphic novel classroom: Powerful teaching and learning with images . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Bitz, M. (2009). Manga high: Literacy, identity, and coming of age in an urban high school . Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bitz, M.. (2010). When commas meet kryptonite: Classroom lessons from the comic book project . New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Brosgol, V. (2011). Anya’s ghost . New York, NY: First Second.

Carter, J. B. (Ed.). (2007a). Building literacy connections with graphic novels: Page by page, panel by panel. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Carter, J. B.. (2007b). Transforming English with graphic novels: Moving toward our “Optimus Prime.” English Journal, 97 (2), 49–53.

Carter, J. B. (2012). Comics. In R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 460–468). New York, NY: Springer.

Donelson, K. L., & Nilsen, A. P. (2005). Literature for today’s young adults (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Friedrich, D. (2014). “We brought it upon ourselves”: Universitybased teacher education and the emergence of boot-campstyle routes to teacher certification. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 22 (2), 1–18. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v22n2.2014 .

Groensteen, T. (2007). The system of comics . Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Groensteen, T. (2013). Comics and narrations . Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Hazlett, L. A., Johnson, A. B., & Hayne, J. A. (2009). An almost adult literature study. The Alan Review, 37 (1), 48–53.

Herz, S. K., & Gallo, D. R. (2005). From Hinton to Hamlet: Building bridges between young adult literature and the classics (2nd ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Jacobs, D. (2007a). “The man called Nova”: Comics as sponsors of multimodal literacy. College Composition and Communication, 59 , 180–205.

Jacobs, D. (2007b). More than words: Comics as a means of teaching multiple literacies. English Journal, 96 (3), 19–25.

Jacobs, D. (2013). Graphic encounters: Comics and the sponsorship of multimodal literacy . New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

Kaywell, J. F. (Ed.). (1997). Adolescent literature as a complement to the classics (Vol. 3). Norwood, MA: Christopher- Gordon.

Kaywell, J. F. (Ed.). (2000). Adolescent literature as a complement to the classics (Vol. 4). Rowman & Littlefield. Lanham, MD.

Kaywell, J. F. (Ed.). (2010). Adolescent literature as a complement to the classics: Addressing critical issues in today’s classrooms . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kress, G. (2000). Multimodality. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp.182–202). New York, NY: Routledge.

Lapp, D., Wolsey, T. D., Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2011/2012). Graphic novels: What elementary teachers think about their instructional value. Journal of Education, 192 (1), 23–36.

Lee, S. J. (2010). The impact of stereotyping on Asian American students. In M. Sadowski (Ed.), Adolescents at school: Perspectives on youth, identity, and education (75–84). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Lesesne, T. (2010). Reading ladders: Leading students from where they are to where we’d like them to be . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Melville, H. (1851). Moby Dick . New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). An expanded sourcebook: Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Monnin, K. (2009). Teaching graphic novels: Practical strategies for the secondary ELA classroom . Gainesville, FL: Maupin House.

Monnin, K. (2013). Teaching reading comprehension with graphic texts: An illustrated adventure . Gainesville, FL: Maupin House.

Myers, M. (1996). Changing our minds: Negotiating English and literacy . Urbana, IL: NCTE.

NCTE. (2014). Call for manuscripts: Re-thinking “adolescence” to re-imagine English [with guest editors Sophia Tatiana Sarigianides, Mark A. Lewis, and Robert Petrone]. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/journals/ej/calls .

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common core state standards for English language arts and literacy in history/ social studies, science, and technical subjects. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/ela-literacy .

Nilsen, A. P., Blasingame, J., Nilsen, D., & Donelson, K. L. (2012). Literature for today’s young adults (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Nobis, M. (2013). Sketchy evidence: Using comics to build better arguments. Language Arts Journal of Michigan, 29 (1), 31–33.

Raible, J., & Nieto, S. (2010). The complex identities of adolescent. In M. Sadowksi (Ed.), Adolescent at school: Perspectives on youth, identity, and education (207-224). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Ravitch, D. (2013). Reign of error: The hoax of the privatization movement and the danger to America’s public schools . New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Rybakova, K., Piotrowski, A., & Harper, E. (2013). Teaching controversial young adult literature with the common core. Wisconsin English Journal, 55 (1), 37–45.

Sadowski, M. (Ed.). (2010). Adolescents at school: Perspectives on youth, identity, and education (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Schwarz, G. E. (2002). Graphic novels for multiple literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 46 , 262–265.

Seglem, R., Witte, S., & Beemer, J. (2012). 21st century literacies in the classroom: Creating windows of interest and webs of learning. Journal of Language and Literacy Education [Online], 8(2), 47–65. Available at http://jolle.coe.uga.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/21st-Century-Literacies-in-the-Classroom.pdf .

Smagorinsky, P. (2008). Teaching English by design: How to create and carry out instructional units . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Spiegelman, A. (1986). Maus . New York, NY: Pantheon.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Stern, D. (1995). Teaching English so it matters: Creating curriculum for and with high school students . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Suarez-Orozco, C., Qin, D. B., & Amthor, R. F. (2010). Relationships and adaptation in school. In M. Sadowski (Ed.), Adolescents in school: Perspectives on youth, identity, and education (pp. 51–69). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Tan, S. (2006) The arrival . New York, NY: Arthur A. Levine.

Wolfe, P., & Kleijwegt, D. (2012). Interpreting graphic versions of Shakespeare’s plays. English Journal, 101 (5), 30–36.

Yang, G. (2006). American born Chinese . New York, NY: First Second.

Yin, R. K. (2008). Case study research: Design and methods . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE