ALAN v42n2 - A Rambling Rant about Race and Writing

A Rambling Rant about Race and Writing

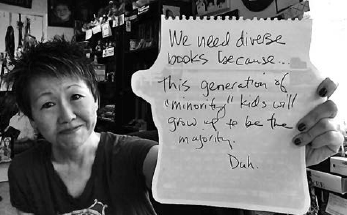

It started with a hashtag and an open-ended statement: #WeNeedDiverseBooks because __ _. A group of children’s/YA authors and industry professionals created a Tumblr page titled, http://weneeddiversebooks.tumblr.com/ , and centered on this mission: “We Need Diverse Books is a grassroots organization created to address the lack of diverse, non-majority narratives in children’s literature. We Need Diverse Books is committed to the ideal that embracing diversity will lead to acceptance, empathy, and ultimately equality.” This effort served as a public call to action. Fill in the blank. Take a photo. Post it. Lots of people did. Kids, adults, readers, authors, and people of different races, religions, and sexual orientations. Different. Diverse. I watched this trending on social media and almost didn’t respond, thinking, “What everyone else is saying is great. There’s probably not much more I can contribute to the conversation.” However, in the end, I decided to throw in my own hashtagged photo. I wrote: “We need diverse books because . . . this generation of ‘minority’ kids will grow up to be the majority. Duh.”

The United States Census Bureau reports that “50.4 percent of our nation’s population younger than age 1 were minorities as of July 1, 2011.” That’s right. When these kids grow up, they will be in the majority. That toddler you see today will be informing public policy and attitudes tomorrow.

After I uploaded my photo on social media, it started to get retweeted and “liked” and shared, and some of my Facebook friends asked me a question in private. It was a good question, one I’ve been asked so many times before. So I posted it to the public:

I thought a few people might respond but was taken aback when more than 200 did. Their comments were questioning, angry, apologetic, heartfelt, confused—the gamut. I was heartened to see how passionately people felt about this subject. Initially, I was going to answer my own question with just a “yes,” and my reasoning was “because.” But the more I started to think about it, the more my thoughts began to crystalize.

As one of my editors, Cheryl Klein from Arthur A. Levine Books/Scholastic, noted in the Facebook comments, I have written outside of my race multiple times. Hell, I have written outside of my religion, my sex, my sexual orientation, my political beliefs, my geographical upbringing, my height. Why? Because I am an artist, not an autobiographer.

It’s funny, but a halo of Asian-ness was dropped on me when I became an author. Prior to that, race was something I wore but didn’t think about, like the color of my eyes (brown) or my hair (black). However, once my first novel, Millicent Min , Girl Genius , came out in 2003 , I ceased to be “Lisa Yee” and became, “Lisa Yee, Chinese American author.” Suddenly people noticed me because of the spectacle of me being Asian in an arena where there were very few of us. Because I had written a book about someone who was Asian. Because, because, because. And it took me by surprise.

“Where are you from?” I’ve been asked so many times that it could be my mantra. I know what the questioners mean; they want to know my race. Sometimes I say, “I’m Chinese American.” But more often I say, “I am from Los Angeles,” only to hear back, “But where are you from?” Though I’ve heard this all of my life, it became louder as an author because I was out there—out in public doing school visits, signing books, speaking at conferences. Me and my Asian face.

Strangers have felt compelled to tell me that their cousin’s friend adopted a daughter from China, that the Chinese restaurant in their town was the best, or that it was interesting that I looked exactly like that neighbor of theirs who was Japanese, or Korean, or Chinese. I have been told that my English is quite good. I have been told that I am a credit to my race. I have been mistaken for Grace Lin, for Paula Yoo, for Linda Sue Park, and for any other female Asian American author out there. One time, a woman congratulated me on a book Lisa See had written. When I explained I was not the author of that book, she asked, “Are you sure?”

Over time, the halo of Asian-ness that had alighted over my head began to slip and tighten around me, binding my arms to my sides. Constricting me. It tried to limit who I was and what I could write. Things were expected of me. Because I was Asian, I was expected to write about that. Why was race so important? Why did this even matter? Why couldn’t I just write? My being an Asian American was no big deal. Well, not to me.

I remember speaking at a mostly all-White school in the Midwest. After, a young Korean American boy pushed his way up to see me. He just stood there and grinned, and at first I didn’t know why.

“You look like me,” he finally said.

So there I was, with my Asian-ness on display, when it hit me. I grew up in Los Angeles where Latinos, Blacks, Asians, are commonplace. But there, in that small town in the Midwest, it was just the two of us in that big auditorium. For that boy, to see another Asian American, one who had just stood on a stage to speak to his school, it was a big deal to have met me. And it was a big deal for me to have met him because, even though we were strangers, we had a lot in common.

I travel a lot. At every school I have visited where there are few Asian Americans, without fail, some of those students wait for me after I have spoken. We greet one another like old friends, albeit meeting for the first time. For now that I have seen outside of the bubble that is Los Angeles or New York, which I visit often, I have noted that the country between the west and east coasts is not as integrated as I thought it was when I was growing up.

When I was a child, there were no Asian American authors I knew of. I had no role models. There were no books about people like me—a third generation Chinese American girl growing up in the suburbs. The most famous Asian American I knew of was news anchor Connie Chung, and she wasn’t a writer.

When I graduated from college, I wrote from a White, male, Southern point of view. Why? Because that’s what I was reading. It was what I knew. The stories of Truman Capote, Thomas Wolfe, and Walker Percy, the plays of Tennessee Williams. We emulate those around us, and it hadn’t occurred to me that I could write like myself. I was still trying to figure out who I was.

When I wrote Millicent Min , Girl Genius , it was without a political agenda. It was not calculated. My editor, Arthur Levine, never told me that no one else had written about a contemporary Chinese American girl. I was blissfully unaware. I didn’t set out to break any barriers. I just wrote about a girl who was Chinese American because that’s who she was. That’s who I was. Millicent’s story is not about issues of race. It is about issues of growing up. Of loneliness and of self-doubt. Even though she is a genius, she is still a kid. Her race is just part of the fabric of the story and by no means the focus.

Later I was told that it was the first time a contemporary photo of an Asian American girl was used on a mainstream novel for young people.

My second book, Stanford Wong Flunks Big-Time ( 2005 ), features Millicent’s enemy, a Chinese American basketball player who is flunking a class. What? An Asian failing school? How can that be? Well it can be, and it does happen. But more than that, it is the story of a boy who feels that he is letting his father down. I hear from a lot of boys about this book. One student, a White boy with blonde hair from Texas, told me, “Stanford is exactly like me.” He didn’t identify with Stanford’s race; he identified with Stanford as a person.

There are volumes of books touting the secrets to publication. And there are people who will try to dictate what you write about. However, I believe that, to be a good author, the impetus comes from within, and you must write well and write a story that is engaging and compelling. Do that, and an understanding about the race or religion or sexual orientation of your characters will follow. Do not lead with social issues; lead with a well-rounded character, and see where that takes you.

I am not an Asian author. I am an author who is Asian. There is a difference.

I believe that it is the right of all artists to determine what they create and not have that dictated to them. I’ve heard that I’ve let readers down because my books were not “Asian enough.” WTF? One critic wrote that I had missed the mark because my characters did not discuss race. Um. No. When I was in school, we didn’t sit around discussing the social ramifications of our race on our relationships with peers; we talked about how much we hated math, whether or not bangs looked good on a round face, and whether Dana’s tattoo was real or temporary.

Even if I wanted to write the definitive Look at Me, I Am Asian, and I Have Overcome Adversity novel, I don’t think I could. Being Asian doesn’t automatically make you an expert on all things Asian, any more than researching does. When writing Good Luck, Ivy ( 2007 ), an American Girl book about a thirdgeneration Asian American, I consulted with experts on things like Chinese school, because even though I am Chinese, I never went to one.

You have to get it right—whether you are writing about your race or someone else’s. This also goes for religion, sex, sexual orientation, ethnicity, ownership of a particular breed of dog, everything. There is nothing more insulting to a reader than if a writer gets things wrong. You will instantly lose your credibility, your readers will abandon you, and some people will think you are stupid.

It is arrogant to think that just because you sympathize with someone or something, that makes you an expert. Don’t automatically assume you know exactly how someone else feels. Because you don’t, any more than I would know exactly how an LGBTQ kid or a Holocaust survivor feels.

Do not presume—but do dare to imagine.

And then talk to people. Talk to people who know more than you do about your subject. Talk to them in person. On the phone. Through emails and letters. Googling is not enough.

When writing Warp Speed ( 2011 ), about a (White male) Star Trek geek who gets beat up every day at school, I was so focused on getting the Klingon correct so as not to offend the Trekkie culture that I wrote that Earth is the largest planet. (Apparently, Jupiter is our largest planet—and yes, some people think I am stupid.) Sometimes we are so busy fussing about details that we miss the obvious.

Three of my novels feature White protagonists. Five of my books feature mixed race kids, including my latest YA, The Kidney Hypothetical—Or How to Ruin Your Life in Seven Days ( 2015 ). Five of my main characters are male; one is Jewish. The main characters of three of my books are Chinese American.

As for needing/wanting more authors who are POC (and by the way, I hate that phrase, “People of Color,” but I suppose it’s not as bad as what it really means—PWANW, a.k.a. People Who Are Not White), yes. Yes, we need POC authors. More POC authors. Yes. This, folks, is a no brainer.

Why? Because there is an innate knowledge that one can gain from experience, from living a life one writes about. But more than that, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), states that, in 2013, the breakdown of available books for young readers is as follows:

“We [CCBC] received approximately 3,200 books at the CCBC in 2013. Of those,

- 93 books had significant African or African American content.

- 67 books were by Black authors and/or illustrators.

- 34 books had American Indian themes, topics, or characters.

- 18 books were by American Indian authors and/or illustrators.

- 61 books had significant Asian/Pacific or Asian/ Pacific American content.

- 88 books were by authors and/or illustrators of Asian/Pacific heritage.

- 57 books had significant Latino content.

- 48 books were by Latino authors and/or illustrators.”

More about this can be found here: https://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp .

By no means am I saying that one cannot write outside one’s race/ethnicity. I have. However, I am pointing out that, when you look at the big picture, the numbers of POC authors are dismal.

We need to encourage publishers, book buyers, and readers to be less exclusive and more inclusive. I should also note that race hasn’t adversely affected my sales. Millicent Min , Girl Genius , for example, has sold about 500,000 copies. We need more POC authors, and more LGBTQ authors, and more diverse authors, just like we need more diverse books.

That said, I repeat that the books need to be well written. Any book needs to be well written before it is published. No one should get a break here. But what we should get is acknowledgement that there is an invisible wall that separates authors who are traditionally in the forefront and those who are clamoring to be heard.

Recently, Chipotle, the Mexican fast food grill that serves burritos as big as your head, announced that it would include short stories on its packaging. Brilliant move. I read ingredients on cereal boxes, so this is a big step up. However, of the writers selected by award-winning author Jonathan Safran Foer, not one was Latino. Chipotle says on its website: “A big goal at Chipotle is to bridge the cultural and linguistic gaps between Chipotle employees. So there is a whole team dedicated to empowering, educating, and training employees to increase internal promotions, cultural sensitivity , and communication skills.” I boldfaced “cultural sensitivity,” not Chipotle.

I don’t think the exclusion was done with malice; I think that it was an oversight, albeit a big one. Yet, so many POC are tired of being oversights. People write books because they have something to say. Let’s try putting some POC authors and more diverse authors at the front and center for a change. We are not trying to take over the world. We are just tired of raising our hands and not being called on.

There is no quota for books that I know of. There is no “do not exceed” number that would cause a publishing house to implode if it published just one more book. Who knows? That book might just be by a POC author. Or it might be from an LGBTQ author. Or it might be from an author exploring not what they know, but what they want to know about, whether that be race or religion or sexual orientation or what it’s like to wake up one morning and be a bug.

I apologize if I’ve been ranting and rambling. I’ve probably contradicted myself within these paragraphs. That’s because I’m still trying to figure it all out. It’s complicated. And yet, it isn’t. This much I know for sure—if a person has the passion and skill for writing a story that must be told, nothing should hold them back from telling it. There is room for all of us.

Lisa Yee ’s 2003 debut book, Millicent Min, Girl Genius , won the prestigious Sid Fleischman Humor Award. Since then, she has written ten more novels, including Stanford Wong Flunks Big-Time, Absolutely Maybe, and Warp Speed. Her latest YA novel from Arthur A. Levine Books/ Scholastic, The Kidney Hypothetical—Or How to Ruin Your Life in Seven Days , covers the last seven high school days of a popular senior who cheated on his Harvard application. A Thurber House Children’s Writer-in-Residence, Lisa has been named a Fox Sports Network “American in Focus,” Publishers Weekly Flying Start, and USA Today Critics’ Top Pick. Visit Lisa at www.lisayee.com or on Facebook, where she practices the art of procrastination.

References

United States Census Bureau. (2012, May 17). Most children younger than age 1 are minorities, census bureau reports . Retrieved June 11, 2014, from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-90.html .

Yee, L. (2007). Good luck, Ivy . Middleton, WI: American Girl.

Yee, L. (2015). The kidney hypothetical—or how to ruin your life in seven days . New York, NY: Arthur A. Levine.

Yee, L. (2003). Millicent Min, girl genius . New York, NY: Arthur A. Levine.

Yee, L. (2005). Stanford Wong flunks big-time . New York, NY: Arthur A. Levine.

Yee, L. (2011). Warp speed . New York, NY: Arthur A. Levine.

by EMW