QBARS - v12n4 On the Importance of the Clone

On the Importance of the Clone

By Clement Gray Bowers

It seems to me that a good many unnecessary words are spent and a good deal of unnecessary confusion results, because we do not use as commonly as we might a very short technical word which expresses clearly and precisely what we mean when we are talking about most hybrids and choice rhododendrons. That word is "clone."

I make this statement at the risk of being repetitive, since I referred to this in an article written for the American Rhododendron Society's Yearbook some ten years ago (see "The Naming of Horticultural Rhododendrons," Rhododendron Yearbook, 4:13-22. Portland, Ore. 1948).

The measures advocated in the previous article have since been amazingly ratified by actions of subsequent international plant congresses, beginning with the London Code of 1952 and followed more recently by emendations and clarifications of the International Code of Nomenclature for Horticultural Plants by the 1958 congress. My only excuse for again dwelling on the subject of clones is the fact that some people are still hazy about them or timid about using the term. In the light of its growing importance, plus the confusion between this and certain other unfamiliar terms, the matter needs further elucidation. It is probable, too, that after ten years, and a host of new members, the readers of this publication will no longer have in mind my words of a decade ago.

For years, gardeners have been thinking in terms of "varieties." Now, the word "variety" can become a conglomerate mess when used alone and with no other designation. Although we usually know by association what is being implied, there are numerous occasions when greater accuracy is required. And as things have progressed in the rhododendron world complications have arisen and the term "variety" has gotten some people into trouble. Abuses have appeared, such as the bad habit of marketing sister seedlings under one "varietal" name, or of using terms loosely which ought to be exact and are so intended.

The simple use of the word "clone," without further designation, would resolve most of these troubles immediately. Hence, the term is becoming more popular among these who understand it, and, as I hope to point out, it possesses more significance than commonly realized.

The need of some term to indicate an individual plant and/or its vegetative progeny (not including its seedlings, brothers, sisters or relatives) has long been recognized in scientific circles. About the time of World War I something was done to relieve this situation by Dr. H. J. Webber, a plant breeder. He coined the word "clone," which comes from the Greek, meaning "twig, spray or slip such as is broken off for propagation." Through somebody's error, it was first spelled "Clon," but Webber promptly corrected this by adding an "e."

Although it seems unnecessary, I think I shall repeat a definition of this term, because I wish to make further comments. Briefly, a clone is a group of plants originating from one selected individual, maintained or multiplied in cultivation solely by vegetative propagation. An example would be almost any named rhododendron or azalea propagated by cutting, grafting, budding or layering rather than by seeds. Its uniqueness lies in the fact that every plant constitutes a piece of the one original plant and is genetically identical with it. In this it differs from a seedling, which is a separate new individual produced by the fertilization (fusion) of an egg-cell by a pollen-cell usually coming from a second parent plant. In the genus Rhododendron seedlings usually differ, at least in minor characters, from their parents and their brethren, while the members of a clone are all genetically uniform.

Because, through long usage, people have been accustomed to use the term "variety" to designate a kind or sort of plant, although it may actually be a clone, horticulturists have been slow to change the old terminology and the term "clonal variety" has been used as a compromise. This is correct enough and is regarded as permissible under the new rules, but is not encouraged for there is no necessity for any term other than clone, which is clear, concise and accurate. Because it can mean only one thing, no one need be timid about employing the word clone when referring to any vegetatively-propagated sort.

Another term which has come forth recently is "cultivar," meaning "cultivated variety." This does not replace the term "clone," nor does it mean the same thing. Most named or hybrid rhododendrons and azaleas are cultivars as well as clones. A cultivar, like a "botanical variety." is a collective term, or may be so used, to denote a hunch of similar seedlings (such as a "variety" of sweet peas or other line hybrids which come true to type from seed), as well as clones, apomicts or other forms. Thus while all clones may be cultivars, all cultivars are not clones, since in the clone it is the individual and not the group which is being identified. The analogy is something like that of the term "azalea," In which all azaleas are botanically rhododendrons, but all rhododendrons are not azaleas. For all practical purposes, the term "cultivar" may be disregarded when the term "clone" is used, since the latter is the more accurate designation. And since it is widely understood that nearly all cultivated rhododendrons having common or "fancy" names are multiplied by cuttings or grafts and hence are clones, it is generally assumed that when a non-Latin name stands alone, as, for example, Rhododendron 'Pink Pearl,' it is automatically a clone. Except when greater accuracy is demanded, therefore, as in a catalogue or in scientific writing, it is unnecessary to use either the word clone, cultivar or clonal variety. The main thing is not to use the single word "variety" unless referring to a seedling group, such as a botanical variety, which is its proper use.

But this does not mean that the clone is unimportant. A moment's reflection will cause anyone to realize that among these plants it is the choice individual rather than the common herd that is important to horticulturists. And this invariably is a clone, whether it be a hybrid or a superior plant within a species group. Most rhododendrons and azaleas do not normally reproduce themselves exactly and reliably from seed excepting in their gross characters. Even among wild species, little variations in color, size, type, habit and form are always present in a batch of seedlings. Given plants with a hybrid ancestry, the extent of these variations is tremendously expanded. Seedlings do not come true. They are often utterly unlike their parents. Their genes are all mixed-up in a complex which geneticists are pleased to term a heterozygous condition. The fact that cross pollination constantly prevails, unless artificially prevented, insures the continuance of this condition. The most obvious way in which the clone is important to gardeners, therefore, is that it insures trueness to type when such trueness is desired. You know exactly what you are getting.

Without splitting hairs about nomenclature, one may go still further in considering the importance of the clone as opposed to the collective group. In the testing of species and other run-of-the-mill seedling populations, it has become increasingly apparent, especially in rigorous climates, that only the rare individual is worthwhile. I would not make this as a blanket assertion, for there are many exceptions, as, for instance, where certain natural species are very useful collectively for a group-effect and where variation is actually desired. We could not get along without large seedling groups. But for specimen plants, for superior color, and sometimes for hardiness, it is often only the unusual variant that proves to be satisfactory. Again and again, individuals appear in mixed populations which, for one reason or another, survive where others fail. These are the choice plants which deserve to be perpetuated and which can be identified only as clones. As we explore the possibilities of new species, it is these outstanding individuals which are important.

|

||

|---|---|---|

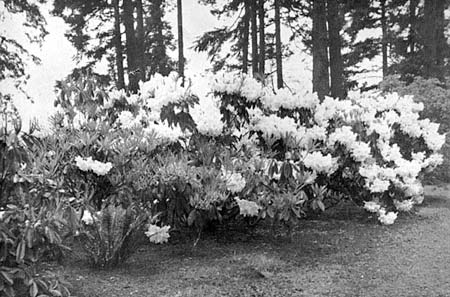

Fig. 46. R. 'Loderi' in the Society Test Garden, Crystal Springs. Cecil Smith photo |

||

|

The importance of special individuals in hybridization work is exemplified by the British records of species crosses. A conspicuous example can be found by comparing R. 'Kewense' (Fig. 47) with R. 'Loderi' (Fig. 46). Both of these hybrids are listed as of the same specific parentage and crossed in the same direction, namely R. griffithianum (seed parent) x R. fortunei (pollen parent). 'Kewense' (Fig. 47) introduced by Kew in 1888, is a mediocre thing compared with 'Loderi' which was the result of a similar cross but with highly selected parents in 1907. The latter was an epoch-marking plant. Where possible, good hybridists like to keep track of the individuals used for parents and often assign them code numbers where a clonal name is lacking. Sometimes a plant, undistinguished otherwise, will perform as an unusually successful parent.

One sometimes hears argument between the naturists and the hybridists as to which is superior, a species or a hybrid. Often this revolves around the personal preferences and prejudices of the discussants - where one is a disciple of wild nature and the other a confirmed horticulturist. Aside from such prejudices and apart from the mass-effect type of gardening, there remains only one measure of excellence by which to judge a rhododendron and that is the clone. Is the individual a good one compared with the others, and does it satisfy the requirements expected of it? This, I submit, is the only criterion by which its merits may be judged, and the question of whether it is a hybrid or a wild species is of little or no consequence, since superior individuals are found in both categories. Improvements are wrought by selection as well as by hybridization.

This brings us to the matter of judging rhododendrons for particular climates and places. Obviously what is "best" in a show may not always be best in a garden, or what is best on the West Coast will not usually be best on the East Coast. Here we must again deal in particulars, not generalities. The more specific the task, the more exact must be the judgment. If we are writing or discussing the merits of something in our garden, we need to be accurate in our statements to the point of citing clones: otherwise our evidence will be of little value to those in other climes. There are too many little quirks within the genus rhododendron to make broad assertions that will be worth anything in universal application. Unlike the annual flowers, there are no all-American rhododendrons. We must get down to definite clones for definite places.

If you will look in that part of the current British Handbook of Rhododendrons dealing with species, you will note that an increasing number of varieties, forms and clones are being separately rated under the headings of their respective species. Almost invariably, they bear a greater number of merit stars than the species-as-a-whole. And in the case of a species gaining an "A.M." or an "F.C.C.," the "A.M." plant is often especially designated as a clone. This is a desirable trend and one which, I think, will increase.

With new methods of propagation making it possible to obtain plants from cuttings more quickly and easily than in former times, including such laggards as the deciduous azaleas, and with the hybridists busy producing finer examples every year, I have no doubt but that the use of clones is going to increase very rapidly. And as rare individuals are found which have special qualities to fit special situations, the areas in which rhododendrons can be grown may be considerably extended. This implies that broad trials must be made and accurate records kept. Such, I think, may become our main line of development in America for the future. And in this, we must pay particular attention to the importance of the individual, that is to say, the clone.