QBARS - v13n1 Biltmore Estate and a New Society Test Garden

Biltmore Estate and a New Society Test Garden

By Dr. Fred J. Nisbet

|

|---|

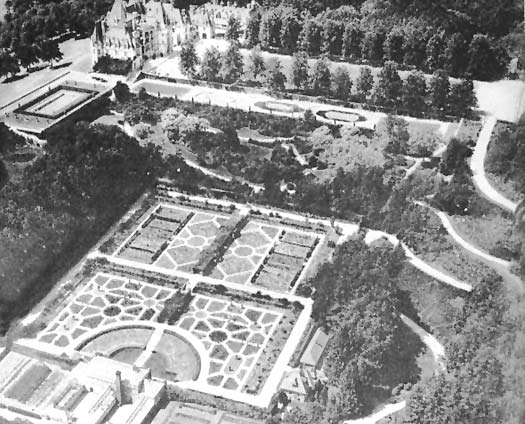

Fig. 2. This aerial view gives some idea of the extent of some of the major gardens |

Large private estates are becoming increasingly rare in America. A variety of factors combine to reduce their number, with high taxes and wages rightly receiving much of the blame.

One of the outstanding survivors of this vanishing group is Biltmore Estate which is unique in that it holds an important place in a variety of fields. This is not surprising, for the man who built this imposing home and its surrounding gardens had a wide variety of interests.

When George Vanderbilt began his project in the mountains of western North Carolina he was still in his mid twenties. Yet he was already some what of a scholar (he was fluent in seven languages) and connoisseur. His major interests included the graphic arts, music, education, landscape architecture, gardening, forestry and conservation (then making their first steps in America) and agriculture.

It is only natural that his home should reflect these interests. What was unusual was the size of the enterprise. It was in 1888 that Mr. Vanderbilt decided that he wanted to build "the finest home in America" near Asheville. Construction of the House and Gardens began in 1890 and was finished in 1895.

By that time the extent of the Estate had grown to about 125,000 acres, or about 190 square miles. By 1895, too, Biltmore was already well known in forestry circles. Gifford Pinchot, the first American trained in forestry, had drawn up a comprehensive forest and conservation plan for the Estate. This was the first such plan in the Western Hemisphere.

Experimental plantings of a wide variety of forest trees were made as early as 1891 and a forest nursery was established to grow the necessary materials for further plantings. Dr. Carl Schenk was brought over from the University of Darmstadt to be the resident forester.

Shortly after the beginning of this century he founded the Biltmore School of Forestry on the Estate. This was the first such school in the New World and many of its graduates became leaders in the field in all parts of the country.

The plans for the landscaping of the property were made by Frederick Law Olmstead, Senior, and were based, in part, on those of Vaux Le Vicompt, near Paris. Here, too, a nursery had to be developed to grow much of the planting materials, as few nurseries of the period carried the wide variety of materials included in the plans.

The location of Biltmore was most fortunate from the standpoint of plant growth. Although much of the land on the eastern portion of the Estate, surrounding the mansion, had been badly eroded farmland, the area was a botanist's and a gardener's paradise. It was located just east of the Great Smokey Mountains at elevations ranging from 2,000 feet to more than 5700 feet. (The highest point remaining in the Estate today is Busbee Mountain at about 3600 feet.) Rainfall was more than adequate and wonderfully distributed throughout the year. The rather heavy soils were acid and, when not abused, capable of growing a bewildering array of plants. Summers are not excessively hot (few days have temperatures in the 90's) and nights are almost always cool. Winters are generally mild and of short duration, although late spring frosts at times are decidedly bothersome.

Here the flowers of the north and the south meet and mingle. Here the firs and birches of the north grow beside the Yaupon and other Florida plants. And, of course, the rhododendrons of the area (including many in the azalea series) form one of the choicest sections of any American flora.

To this developing estate, set in such a potentially fine area, came a young graduate of Cornell named Chauncy Beadle. He arrived in 1891 as a planting superintendent for Mr. Olmsted. He remained as Superintendent of the Estate until his death in 1950. Mr. Beadle was a first rate landscape engineer, a good designer, a perceptive plantsman and a quiet, kindly gentleman. He roamed the mountains and savannahs of the southeast in search of rare plants and brought them back to Biltmore. He exchanged plants with botanists, gardeners and nurserymen and, in the process, made the collection at Biltmore extremely varied and fine.

During the formative years at Biltmore Mr. Vanderbilt and Mr. Olmsted planned a large and fine arboretum. Professor Charles Sargent of the Arnold Arboretum was brought in as advisor. He was most enthusiastic about the project and felt that the combination of soil, climate and great expanse made it potentially "the finest arboretum in America." He did, however, have a bit of advice for Mr. Vanderbilt. Too many such projects, he claimed, were begun with high hopes but foundered later because of a lack of operating funds. He suggested an adequate endowment. Mr. Vanderbilt saw the wisdom of this and asked what would be considered "adequate." Professor Sargent said, rather casually, that a million dollars should do. That was the end of the Biltmore Arboretum.

All of the remainder of the plans of Mr. Olmsted, however, were carried out and remain today, essentially as they were built and planted. One exception is that thirteen acres of the Pinetum have been given over to the Chauncy Beadle Memorial Azalea Garden. Here grows the finest collection of native American azaleas in the world. These plants were collected over a period of ten years from trips that ranged from New Hampshire to Florida and from Michigan to Texas. Rarities such as Rhododendron furbishii , R. prunifolium , R. calendulaceum in its pure white form and others are common in this collection. In addition there are many hybrids and Asiatic kinds, totaling some 40,000 plants.

Great changes have occurred on the Estate since Mr. Vanderbilt's death in 1918. The great variety of agricultural enterprises, which constituted essentially a private experimental station, has been reduced to one, dairying. Today about 3500 acres are devoted to one of the finest and largest dairy herds in the world. Some 1500 registered Jerseys produce part of the milk needed for the Biltmore Dairy, which operates in both North and South Carolina.

In 1917, shortly after Mr. Vanderbilt's death, a tract of 85,000 acres was turned over to the government as the basis for the Pisgah National Forest. Other projects were allotted land so that now there are but 12,000 acres remaining in the Estate. It is on this land, however, that all of the intensive gardening and forestry was located, so that the heart of the Estate is much as it was in Mr. Vanderbilt's day.

But what of the future? At present, Biltmore is held in trust for the two grandsons of Mr. and Mrs. Vanderbilt, George and William Cecil. These two young men are thoroughly devoted to their home and intend that it be kept as an entity. As visitors are now admitted to Biltmore House and Gardens, the gardens, the three mile long Approach Road (featuring thousands of Rhododendron catawbiense and R. maximum ) and Biltmore House are kept in good condition. Some 19 of the 250 rooms in the mansion are arranged to show the magnificent treasures of art, books and furniture which Mr. Vanderbilt collected to furnish his home. About 65,000 people, from all over the world, visit the Estate each year.

|

|---|

Fig. 3. The conservatory and greenhouses stand at the side of the four acre Walled Garden, called the finest English garden in America. Biltmore photo |

The large conservatory and the greenhouses were entirely rebuilt last year and new collections of Orchids and Acacias are now being assembled. New propagating and nursery areas have been built for the new rhododendron and holly collections.*

Although a major arboretum is not being planned, several minor collections are being assembled. These include Magnolias, Japanese Maples and Camellias. This program will add much interest to the gardens for all visitors.

It is in this grand setting that the latest Test Garden of the American Rhododendron Society is to be located. This should prove to be of considerable value to gardeners' in the area as it is our feeling that much of the Southeast is wonderfully adapted to growing a wide range of rhododendrons. Growth in this direction awaits only specific information as to the adaptability of the various kinds to the cultural conditions encountered here.

We hope that all members of the Society will make periodic visits to watch the progress made over the years.

*A.R.S. Bulletin, July 1958.