QBARS - v24n2 Rhododendrons at Flowering Time: Japan, 1969

Rhododendrons at Flowering Time: Japan, 1969*

Frank Doleshy, Seattle, Wash.

*All republication rights reserved by the author.

PART I

|

|---|

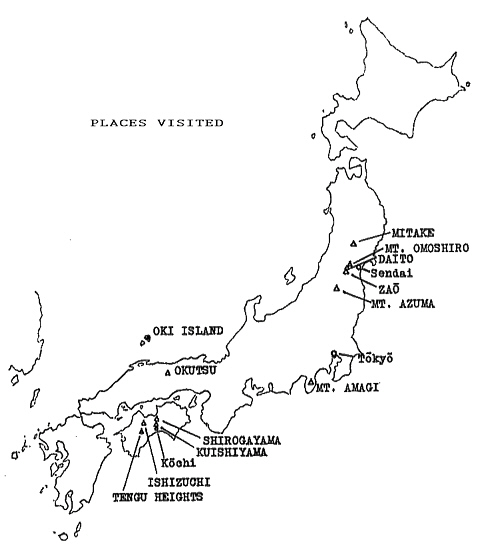

When Mrs. Doleshy and I went to Japan in 1965 and 1967 we concentrated on the collection of seeds. Our 1969 trip, on the other hand, was simply for the purpose of learning more about the rhododendrons and other plants. It turned out to be a continuous hard-hitting seminar, often rain-soaked and short on sleep, but sustained by the best food in the world, plus Japanese sake and Japanese hospitality. Our teachers were the botanists who direct the Makino Botanic Garden and the Tohoku University Botanic Garden, plus a number of the most distinguished forestry officers we have ever met, as well as two gentlemen who, we hope, will soon organize the Kanto Plain Chapter of the American Rhododendron Society. Also not to be forgotten are various farmers, inn maids, law students, etc" who knew which ridge to climb in order to see the rhododendrons.

This account will lightly skip over the more technical observations and, instead, will be concerned with potential horticultural values, as well as the problems and pleasures of travel to Rhododendron areas. Then, if interest is evident, I'll write another article about such things as distribution and habitat limits.

A full day in Tokyo was enough to overcome the much-exaggerated effect of setting our watches back 8 hours. The next noon we flew down to Kochi, on the south coast of Shikoku: home of the rather new but very important Makino Botanic Garden, which we had visited in 1967. During that brief tour, the Director, Mr. Yamawaki, had told us several startling things about rhododendrons in Shikoku, and we had assured him that we'd be back.

This year, Mr. Yamawaki had delayed an expedition of his own to Yakushima, and he was waiting for us when we arrived at the garden. Going first to a conference room in the library building, we were joined for tea by two other gentlemen who we took to be staff botanists until one presented his card, "NHK-TV", and pulled out his portable camera. The other, from the newspaper, got out his notepad.

These people more than did their duty and were also good plantsmen, as proud as Mr. Yamawaki to show us the Botanic Garden. A unique feature here is the establishment of distinct growing zones with three kinds of rock, limestone, serpentine, and the local chert. Some of the individual rocks are of substantial tonnage, and their placement suggests natural landscapes.

At a prearranged time, Mrs. Doleshy and I went with Mr. Yamawaki to the new capitol building of Kochi Prefecture and were joined by Miss Hosokawa, the Prefectural Librarian, called in to translate because of uncertainty about our Japanese language ability. Somewhat in a daze, we were seated by Governor Mizobuchi at the low conference table from which he operates. We learned that he often visits the high peaks but is known for bad luck with the weather and seems to attract a typhoon whenever he starts climbing.

Our final stop was the forestry building. Mr. Morio, the Chief Forestry Officer , had sent his regrets because he was in Tokyo, but his two principal assistants were there to discuss practical matters of food and rain-gear for the next day's trip to Kuishiyama, a mountain north of Kochi.

Getting up early in the morning, we watched the TV news broadcast as we ate breakfast and concluded that their cameraman had been very kind to us. We saw our friend, Mr. Yamawaki, on the same channel. A polished performer, he told of the plants in bloom and also discussed a new hut to be built in the mountains.

Downstairs, we found Mr. Yamawaki. Miss Hosokawa and several forestry people arranging their pack sacks in two forestry cars. Our rented Toyota was not needed, so we left it at the inn's parking lot and rode in style on the freshly-laundered white seat covers of their big, black Nissans. Mr. Yamawaki had mapped out a circular tour of central and northwest Shikoku for us, and Kuishiyama was the first objective. Here, a large population of rhododendrons extends from the 1176 meter summit down to an elevation of 1050 meters or less. The lower limit is probably man-made, since the rhododendrons extend in some places to the edge of clear-cut areas now being reforested.

Varieties of R. metternichii

The evergreen rhododendrons on this mountain, with their (usually) 7-part flowers and indumentum clad leaves, were easy enough to recognize as R. metternichii . However, because of marked differences in the thickness of indumentum, and more or less visible differences in growing habit, the R. metternichii of southwestern Japan (excluding Yakushima) is divided into two varieties:

First, the heavily-indumented and usually rather compact-growing R. metternichii var. metternichii , or TSUKUSHI SHAKUNAGE.

Second, the thinly-indumented, often more open-branched R. metternichii var. hondoense , or HON SHAKUNAGE.*

*Readers not familiar with present-day names are urged to consult the English language edition of Ohwi's Flora of Japan, published by the Smithsonian Institution, 1965.

(You can see, I'm sure, why we prefer to use the Japanese names. They can be learned with ease, keeping in mind that SHAKUNAGE is the general term for thick-leaved evergreen rhododendrons, and that TSUTSUJI is the term for Azaleas plus certain other thin-leaved rhododendrons, such as R. keiskei and R. semibarbatum .)

As we looked at the Kuishiyama plants, Mr. Yamawaki explained that the R. metternichii population on a particular mountain is almost always quite uniform, with only slight differences from plant to plant. If they have heavy indumentum they are readily classified as var. metternichii , and a thin, appressed indumentum labels them as var. hondoense . However in Shikoku and some other districts, one may climb a mountain and find a uniform population of rhododendrons which is intermediate between var. metternichii and var. hondoense . This was true on Kuishiyama; the plants were close to var. hondoense but had somewhat more indumentum than typically found on this variety.

Faced with such a puzzle, the automatic reaction of some people is to say "natural hybrid." However, this view is hardly supported by our observations of R. metternichii at (so far) 18 places in Japan. We have never seen a swarm of varying plants in one particular locality, and it probably makes more sense to suggest that the R. metternichii of southwestern Japan is a plastic species which differs from one mountain to another because of "survival of the fittest" in each different environment. This latter suggestion is also an oversimplification, but it is probably a useful concept for the non-specialist who doesn't want to go too deep.

Since we like indumentum, we usually favor var. metternichii over var. hondoense . However, the Kuishiyama plants (close to hondoense ) had a characteristic we've seldom seen; the ability to grow old gracefully and magnificently in a shaded situation. With gnarled trunks and huge, horizontal branches, they looked like jungle trees. Flowers were clear pink and attractive but sparse this year. Mr. Yamawaki wanted to correct the impression that this was always true; I had photographed him sitting on the trunk of a giant plant, and he gave us a slide of the same plant taken one year previously, when it was hard to see anything but flowers.

The other plants here were our first introduction to the mountain flora of Shikoku. Trailside brush was often R. pentaphyllum , or AKEBONO TSUTSUJI, with every variation of reddish color on the leaf margins. To our surprise, many of the graceful little trees were this same plant, and we were sorry to be too late for the flowers. (The Japanese name refers to the pink color of sunrise.)

Great masses of salmon-red flowers were to be seen on the local form of R. weyrichii , called ON TSUTSUJI in Japanese but often patriotically referred to as R. shikokianum (the name used by Makino). Also present were the more delicately-colored salmon-pink flowers of R. kaempferi , or YAMA TSUTSUJI. At the time, we couldn't understand why these were passed by like dandelions, but we were less surprised after seeing these flowers everywhere we went in Japan - beside roads, overhanging streams, and growing from the stone walls of rice fields.

Besides rhododendrons, we got acquainted with the plants which supply toothpick wood, funeral sprays, and soup flavoring, sending home one of the last.

The Limestone Rhododendrons

Next came a half-day drive to Shinden, in the west-central mountains of Shikoku. After getting there and eating lunch, Mr. Yamawaki hustled us up the new road to Tengu heights, a magnificent Karst Plateau, with drifts and droves of oddly-weathered limestone rocks which are usually the tops of pinnacles poking up through the thin soil. Between the rocks there was a low cover of bamboo, occasionally topped by a Pieris and with an interesting understory of violets, club moss, etc. Starting down the slope at the north rim, we got into trees, with undergrowth of white Paeonia , yellow Abelia , and various plants of the Lily Family. Our objective was about 30 meters downhill, a flat-topped buttress of the limestone, covered with perfectly normal and heavily-indumented R. metternichii var. metternichii !

Mr. Yamawaki told us that rhododendrons are rare indeed on the range of limestone ridges which includes this plateau, and he pointed out companion plants which are found only on limestone. However, rhododendrons dominated the flat top of the buttress, perhaps 75 meters wide and long. Those in full exposure were as tight and compact as any mountain-top specimen, and those under trees had the usual somewhat stringy appearance. Flowers were fairly abundant and an attractive pink, although past their best.

This limestone-dwelling population raises interesting questions. Rock fragments were plentiful at root depth and looked the same as the limestone elsewhere. Also, we have found that solid pieces react vigorously with cold, dilute hydrochloric acid, leaving no residue, so it would seem that this rock is an ordinary calcium limestone rather than dolomite. Soil depths possibly averaged 30 cm., allowing most roots to avoid bedrock, but it would be difficult for them to avoid the rock fragments in the soil. Also, several very good plants grew on the steep corners of the buttress where there was little soil. Further investigation may reveal some unusual circumstances but, at present, we can only describe this as a case of normal looking R. metternichii var. metternichii in thin soil over limestone.

Mrs. Doleshy and I had reservations for the night at a Shinden inn, but Mr. Yamawaki took us all to a small mountain inn and phoned down to Shinden to tell them we were in botanical conference. After baths, we settled down to a dinner enlivened by Japanese spring foods from species of Osmunda, Polygonum, Fagus, Acer, Aralia, Petasites and Lentinus . Such a dinner could, possibly, be obtained in Tokyo for about $50 per person, but our total bill for dinner, room and breakfast was about $4.80 apiece.

The next day Mr. Yamawaki left us for his somewhat delayed Yakushima expedition, and we were sorry to have held him back. But we later learned that he had 12 continuous days without rain - phenomenal for a spring visit to Yakushima - and we felt better. Our own route was north via the new Chiyoshi Pass road to Omogo, at the foot of Ishizuchi, highest mountain in southwestern Japan. With some worry, we accepted the suggestion that the Shinden Police Chief ride with us because of business in Omogo. However, he issued no citations, and he knew the good places to stop for coffee and picture-taking.

At Omogo is the grand old Keisentei Inn: red carpets and brass rails in the halls, rooms so plain and rich that they might have been built for a 15th Century lord, and one's personal prestige a matter of knowing forestry officers, rather than spending large amounts of money.

Our first visitor was Mr. Miyazaki, a gentleman we had been advised to look up because of his knowledge of rhododendrons. He arrived as we finished unpacking and invited us to his nearby home. A spring downpour had started, but we borrowed umbrellas from the inn and were glad we went. His collection included plants from many parts of Japan, beautifully grown, and we learned how to recognize some of the things we'd see the next day.

Next to come was the Forest Superintendent, Mr. Michikura, who announced that he'd like to climb Ishizuchi with us. Delighted with his friendly informality, we accepted, but weren't aware of his position until much later. This was shown on his card, but we still have trouble with titles written in Japanese.

|

|---|

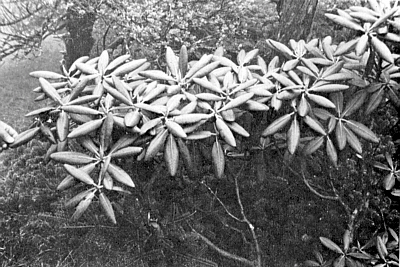

Fig. 16. R. pentaphyllum foliage beside Ishizuchi trail. |

The rain stopped as we ate breakfast, and the sun was out when we started up the long trail. R. pentaphyllum was common at the upper levels of the deciduous woodland, and it appeared to take over any disturbed ground. For at least one kilometer there was a continuous display of small plants which had colonized the edges of the trail (FIG. 16). And, on the park-like slopes above and below, there were numerous trees of the same species, about 5 meters tall and twice as broad. On the small plants, the leaves had the characteristic maroon coloration, as an edging or sometimes extending over much of the leaf, but the mature trees had little such color. We are not sure whether this is because of a difference in the time of leaf emergence or whether there is an actual difference between small plant and large plant leaves, but we suspect the latter.

No flowers were left on these. However, as we emerged from deciduous forest to rocky slopes, we saw several plants of the R. reticulatum tribe (MITSUBA TSUTSUJI) covered with their lavender flowers. After crossing a great slope of bamboo we entered a stand of small conifers and then came to the summit ridge. Using the famous chains, we worked up past the new concrete and aluminum residence of the Shinto priests and reached the stone shrine on the secondary summit. Here, in swift-flowing fog, the visibility varied from 10 to 50 meters, and Mr. Michikura discouraged our attempting the traverse to the highest summit, saying that the large, evergreen rhododendrons were below anyway. At the shrine, cracks in the rock contained R. tschonoskii , the KOME TSUTSUJI or "Rice Azalea." Also, there were pink flowers of Shortia , but neither plant put its head out beyond the main surface of the rock.

R. brachycarpum on Shikoku Descending a short distance, we went out the southwest ridge, in search of the plant which had brought us back to Shikoku. In 1967 Mr. Yamawaki had mentioned R. brachycarpum (HAKUSAN SHAKUNAGE) on the two highest mountains of Shikoku. We took his word, but were so amazed to learn of R. brachycarpum this far south that we soon started planning our 1969 trip.

|

|

|---|---|

Fig. 17. R. metternichii var. metternichii , southwest ridge of Ishizuchi. Strips of deep color prominent on the emerging flowers. |

Fig 18. R. brachycarpum in Ishizuchi, far from the areas where it is usually thought to grow. |

The first rhododendrons sighted were not brachycarpum ; instead we became aware of a ribbon of pink color through the fog, along the very top of the ridge, and this turned out to be an almost hedge-like row of the heavily indumented. R. metternichii var. metternichii (FIG. 17). Almost at the same time, we spotted our first R. brachycarpum , growing just a few meters lower (FIG. 18). However, this had no flowers, and we felt that it would stay there while we looked at the display above.

The R. metternichii plants were very compact, usually 1-1½ m. tall, and the flowers were abundant, some still bursting out of deep-pink buds. To us, the flower color seemed exceptional clear pink of medium depth, with quite a lot of darker color on the edges and in stripes down the corolla. The leaves were different from any we had seen in 1967 on the Kyushu populations of this variety: smaller and often so tightly rolled that they approached the pencil shape of R. makinoi . The indumentum was heavy and tan-yellow, almost like that on some species of the Taliense group, and it was much darker on leaves with the lower surface partially twisted up toward the light (a characteristic we've since noticed in other populations). However, in this wind-swept location, many leaves had their indumentum partly worn off and some were completely bare, just as on the typhoon-blasted Yakushima rhododendrons. When the fog broke, we could see that these plants extended down the cliffs of the northwest side of the ridge but apparently not very far.

With the R. metternichii were plants of Vaccinium and R. tschonoskii , the latter gnarled and waist-high with leaves hardly bigger than a grain of rice. Also, the pink flowers of Shortia were opening under the shrubs.

The R. brachycarpum , a few steps down the slope, was a healthy, flat topped plant, perhaps two meters across, growing in the slight shelter of scrub conifer and surrounded by dead stalks of dwarf bamboo. (One year earlier, most of the bamboo on this mountainside had gone through the flower-and-die cycle which is thought to occur at 60-100 year intervals.)

The most remarkable thing about this R. brachycarpum was its perfectly normal and recognizable appearance, even though growing 500 kilometers southwest of the generally-accepted limit of its range. This was the only specimen in sight near the top of the ridge; to find more we descended about 30 or 50 meters, more or less skiing down the bamboo stalks on the soles of our shoes (and occasionally finding a hidden, hip-deep hole).

Down here among scattered trees there were large and small plants, indicating active regeneration. However, we saw only one flower bud, not yet nearly open. R. metternichii was absent, and it appeared that R. brachycarpum preferred the more sheltered environment. This seems upside down, because R. metternichii is common on the south island of Kyushu, while R. brachycarpum grows in northern Japan, usually on open, rocky ridges. However, we were later to see a strangely parallel plant community in northern Japan, on Mt. Daito.

Going down the trail, we tried hard to find some year-old seed of R. pentaphyllum , with no real success. Mr. Michikura couldn't find any either and volunteered the idea of getting us some new-crop seed later in the season - an offer which was accepted with enthusiasm. (Just as this account went to the Editor, seeds of R. brachycarpum, R. tschonoskii, R. pentaphyllum and R. metternichii var. metternichii have arrived from Mr. Michikura. These are being distributed through the A.R.S. Seed Exchange under his name as collector.)

The next morning had to be reserved for hurried work on specimens. When finished, we asked our maid if we could have early box lunches to eat in the front garden, on the rocks of the beautiful gorge. The response was two complete portions of a banquet they were serving that day, brought outside for us. We had barely finished when Mr. Michikura appeared, this time with four companions in a large forestry car. We followed them up a side canyon in the lower part of the Ishizuchi range and walked a few hundred meters to a forested ridge with undergrowth of R. metternichii .

Unlike the high-altitude population, these had thin indumentum and were apparently much closer to var. hondoense than to var. metternichii . In deep shade at an elevation of only 1060-1100 meters, their habit of growth was loose and open, but we again noted that such plants can be attractive. Large specimens had quite a few flowers, and the smaller ones often formed a knee-high thicket. (Pacific Northwest members can think about this as a substitute for ground cover of Salal.)

Our two-car caravan then headed back to the main valley and up onto a new skyline road under construction. When completed, this will be a mountain super-highway to the north coast of Shikoku, but we made appropriate stops for dynamiting and picked our way through rough tunnels with streams on the floor. Near the end of construction, again at an elevation of about 1100 m., we stopped and climbed down a north slope to reach a stand of R. metternichii . These plants were tall, and the spreading tops were thickly covered with shiny, dark-green leaves. Indumentum was moderately thick, just about half-way between that of var. metternichii and var. hondoense , and I don't think that Mr. Michikura was any more comfortable than we were as his rangers attentively waited for the verdict. I hope they were satisfied with a discourse on intermediacy, plastic species, etc.

Horticultural Impressions

Omogo was the last area where we were able to examine a population of R. metternichii var. metternichii during 1969. To date, we have seen this variety at five localities; our observations, for what they are worth, can be summarized as follows:

Shakutake, northern Kyushu: Plants noted for depth of flower color and apparently very floriferous, but the leaves are dull-surfaced and do not have outstanding indumentum. Seed collected in 1967, distributed as No. 35. Plants distributed by U. S. Dept. of Agriculture as P. I. 330367, spring 1970.

Mt. Kuju, northern Kyushu: A population highly regarded in Japan. Leaves are long, narrow, deep green and shiny, with an interesting cycle of changes in the color of the indumentum (rich orange on year old leaves). Seed collected in 1967, distributed as No. 38.

Shiromizu-taki at or near the southern limit of R. metternichii in Kyushu proper: These plants have large leaves held out in more or less thatched arrangement. Seed capsules suggest a very large flower, and we have planned a second visit to check this. Seed collected in 1967, distributed as Nos. 41 and 42. Plants distributed by U. S. Dept. of Agriculture as P. I. 330368, spring 1970. (Surprisingly, during a two-week interval of 1969, a visitor from New Jersey and a visitor from Australia commented favorably on their young plants from this seed.)

Tengu heights, Shikoku, discussed above: Plants seem lime-tolerant and have a very good habit of growth in the open, not so good in shade.

Ishizuchi, Shikoku, discussed above: Seems outstanding for striped flowers, compact habit, small, recurved leaves. Habit and leaf characteristics may not be quite the same when grown at low elevations in gardens.

After our Omogo sojourn we went on "vacation", heading for Matsuyama and Dogo Spa via high-speed Highway 33, then taking a leisurely trip east on the highway which follows the Shikoku coast of the Inland Sea. The first part of this had the expected dream-like beauty, but the central coast mainly had vistas of mile-long paper mills, smelters, and heavy trucks roaring through the smog. This drive is only for those who love Japan very-much. However, a few blocks from the world's second biggest paper mill, we stayed at an inn which kept the air clean with hedges of conifers and Azaleas, and we could hear nothing but the water in the garden pools.

Turning inland and south, we reached the little town of Motoyama at the foot of Shirogayama, one of the larger mountains in north-central Shikoku. The rooms at our inn had private gardens, and we were urged to investigate as we drank our welcoming tea. Then we were directed to forestry headquarters, half a block down the street, and found that we were expected. Two officers came to our room for discussion of the next day's plans, over sake and sashimi (sliced fish, not cooked), but we never could get a bill for this. As at other places, we thought that we were the hosts but later learned that this was an error.

Next morning the forestry car brought three people and picked up two more en route to the mountain, as we followed in our faithful Toyota. Taking to the trail, we started seeing R. metternichii at about 1100 meters elevation and had it in sight almost continuously to the 1470-meter summit. This is an immense population, the largest we have ever seen of any Rhododendron. A uniformly thin indumentum placed it close to var. hondoense . However, in such a broad range of elevations, leaf size and plant habit varied; the leaves at 1100 m. were at least twice as long as those at the summit and much farther apart on stems. Flower color varied moderately, and some were nearly red.

Growing with the R. metternichii were numerous large and small plants which, we agreed, were probably R. pentaphyllum. But no one was willing to rule out the possibility that some, especially on the summit, were actually R. quinquefolium , the GOYO TSUTSUJI. Perhaps there are people who can readily distinguish these two species in late spring by foliage alone, but we need to study the live plants and herbarium material much more. (See FIG. 16.)

Elsewhere, we had been too early to see new foliage on R. metternichii , and this was also true of full-size foliage buds on the Shirogayama plants. Here, however, there was new foliage on young seedlings and, often, on the bud growth which breaks from large trunks near ground level. In both cases the new leaves were bright red or brownish red, nearly flat, and without any continuous coating of hairs.

Back at the inn, we had an interesting opportunity to see the emergence of full-size leaves on a mature plant, brought down from the mountain. The new leaves were almost full length but rolled into thin, tubular shapes and completely covered with white hairs, even on the midrib.

The maid here was one of several who considered it a duty to work on our Japanese pronunciation and grammar, and she also knew something about plants. This particular Rhododendron, she said, had come from a point near the summit; the new foliage was brought out by the warmer weather down at the inn, and she saw nothing unusual about the coating of white hairs. This aroused our curiosity, but we had to wait several days to find out whether a juvenile (practically hairless) and' a mature (hairy) form of new foliage was found on any other population of var. hondoense .

From Motoyama we returned to Kochi via Highway 32, which plays leap-frog with the railroad in a giant gorge extending most of the way through Shikoku. After turning in the car we took our baths and went down to the lobby, where Miss Hosokawa and some of our forestry friends were waiting. Tonight, at a dinner party, we were to make our report to Mr. Morio, the Chief Forestry Officer.

The party started with serious Rhododendron talk, and this continued until Mr. Morio announced that one of the maids serving dinner was a famous dancer, and that he would sing her accompaniment while she performed one of the traditional dances of Kochi. This enlivened the party to the point where rhododendrons sometimes had to be forgotten in order to teach us the finer points of formal dining in southern Japan.

The next morning we took an early train north, but Miss Hosokawa was at the station with a gift for us; a beautiful and comprehensive Rhododendron book only published a few days before, and with many contributions from Japanese members of the A.R.S.

North across Honshu

|

|---|

Fig. 19. R. metternichii var. honodoense at Okutsu; new leaves covered with white hairs except at midrib. |

Crossing the Inland Sea to Honshu (Main Island), we went to Okutsu, a town almost due north of Okayama city and about 2/3 of the way across Honshu. Our interest here was observation of a presumably :typical population of R. metternichii var. hondoense ; we had picked this location because it is fairly close to the center of hondoense distribution and is remote from any recorded occurrences of R. metternichii var. metternichii or R. brachycarpum .

Okutsu itself is a famous hot springs resort. Our inn had large, luxurious Japanese rooms, modern art in the corridors, and maids who wore uniforms during the day but kimonos when they brought dinner. They wanted to start us soaking right away, but we explained how hard we had tried to get here in 1967 and that we wanted to find out about the rhododendrons before relaxing. This was no problem. They drew a detailed map showing that we had to go down the highway 1½ kilometers and turn left onto a wooded ridge - so we took our baths.

As they had said, it took only about 20 minutes to walk to the rhododendrons the next morning. Flowers were over and gone, possibly because of the low elevation (350 m.), or possibly because flowering is triggered by day lengths, which are longer as one goes north.*

*After the vernal equinox (about March 21st).

The latter view is supported by Mr. Wada's observation that this variety blooms earlier in northern Shikoku than southern Shikoku.

Both young and old plants had new foliage, and this confirmed what we had seen at Shirogayama: flat, bare leaves of reddish color on seedlings and ground-level shoots; tightly rolled hair-covered leaves emerging from the full-size buds. At this place, however, there was one conspicuous difference in the pattern. The white hairs on the larger leaves did not cover the midrib, and this was red. (Fig. 19).

In the wild, the mature plants were about 3½ m. tall, open-growing but graceful. Those brought in to gardens were usually very compact, and the new leaves were as attractive as flowers.

The next day, via car, train and airplane, we went north to Oki Island, home of the Rhododendron which has been so generously introduced to other countries by Dr. Rokujo. We had hoped that he might be able to join us there, but his reply came from the Savoy Hotel, in London, and indicated a severe load of professional duties.

The inn at Oki was fine but, as sometimes happens, agitated at entertaining their first foreign guests. An English-speaking assistant manager called at our room frequently, first with picture post cards of this wonderfully scenic island, then with maps, then to plan the next day's trip, then to examine our shoes, socks and pants to see if they were thick enough to protect against the mamushi (the common poisonous snake of Japan).

The next morning, in a moderate downpour, he led us to the bus station and told the driver and conductor to let us off at the best Rhododendron place in the central hills. They discussed this with all the other passengers and finally stopped at the end of a brushy, trail-less ridge. Out we went, in a storm now getting down to business, and were told that a southbound bus would come by 5 hours later.

Seeing no mamushi snakes, we climbed the back of a gravel pit and started into the near-jungle. This featured luxuriant vines of Smilax china , which has attractive flowers and thorns so thin and sharp that they almost look harmless. Then, about 40 meters above the road, we found the first Rhododendron, a plant which would be welcomed in any garden.

This ridge had been logged off, probably at least 20 years earlier, but a few large conifers remained, surrounded by open woodland of maples and other deciduous trees, plus reforested pine and cryptomeria. The thick undergrowth was full of Clematis, Arisaema , and various Ericaceous plants. Some of the rhododendrons pushed up through this, but they were more numerous on steep, rocky slopes where the other plants were not very thick. They continued up the ridge throughout a vertical range of 50-70 meters then stopped, apparently at a geological break. The whole ridge was thin-soiled, and the rhododendrons grew where the rock was granular (perhaps a schist) but did not grow above on tight-surfaced rock (probably andesite).

After some upward probes we returned to the rhododendrons; these were obviously R. metternichii and can probably be considered a form of var, hondoense which has developed distinctive features in isolation. Foliage was dense, a deep green above, and with thin indumentum which varied from pale buff to pinkish. Leaf tips were nearly round, and the margins curved downward, much as on the Yakushima variety. A surprising thing was the ridging of the leaf surface from base to tip, as sometimes seen on R. thomsonii . Flowers were gone, but there had been many, and the unusually large seed capsules suggested that the display is spectacular. Several year-old capsules still contained seed; this has germinated fairly well, and will be distributed by the Seed Exchange (our No. 75).

Even at the low elevation of 200-270 meters, leaf size and plant stature were somewhat smaller than we had seen in other populations of var. hondoense . However, the plants were by no means dwarf, and main trunks 8 or 9 cm. in diameter were big enough for footholds on a steep slope. Later, looking around the main town of Saigo, we could see why this Rhododendron has sometimes been called a dwarf. Every souvenir, grocery and drug store had them for sale in pots. Grown this way, the leaves were usually about half the length and width of those in the wild. And, when we left Oki, at least 22 of the 66 seats on the airplane were shared with such plants.

Horticultural Impressions

This was our final opportunity to see R. metternichii var. hondoense in 1969. On the basis of our brief examinations, the horticultural features of various geographical races (including those which are intermediate between var. hondoense and var. metternichii ) can be summarized as follows:

Iwaya Hill, north of Kyoto, in Honshu: Robust and thick-foliaged on this open hill-top. Indumentum on mature leaves is sometimes darker than usual for this variety; new foliage on young plants is often an attractive pink. Seed collected in 1965, distributed as No. 5.

Kuishiyama, Shikoku: Capable of very heavy flowering in a good year; old plants are picturesque.

Canyon road near Omogo, Shikoku: Smaller plants grew as a fairly dense knee-high ground cover. Produced a moderate quantity of flowers even though shaded by large trees.

Skyline road near Omogo, Shikoku: Large plants; comparatively dense foliage consisting of long, shiny, deep-green leaves.

Shirogayama, Shikoku: This huge population included some plants with nearly red flower color. Also, on specimen transplanted to the inn's garden, the tightly-rolled new foliage had a complete covering of white hairs.

Okutsu, Honshu: New foliage also highly decorative: white with a conspicuous red midrib. Apparently quite floriferous.

Oki Island: Seemed to us the finest yet seen. (However, Mr. Wada has told us that we should visit a Kii Peninsula population, said to be the best of this variety in Japan.) Please note that we have not seen each population at each stage of growth and therefore may be neglecting features which are outstanding in other seasons.

(TO BE CONCLUDED)