QBARS - v25n2 Flowers from Kurume to Yakushima: Japan 1970, Part 2

Flowers from Kurume to Yakushima: Japan, 1970

Frank Doleshy, Seattle, Wash.

PART 2

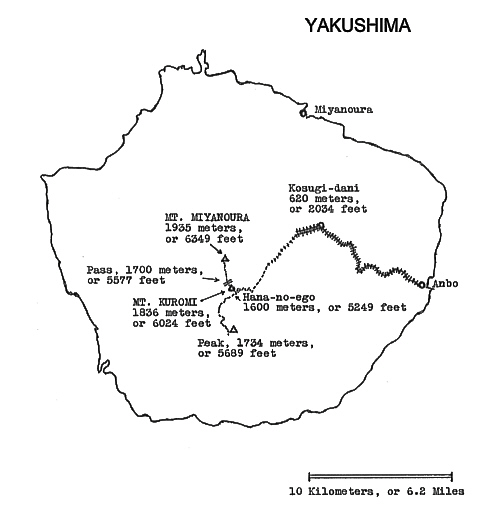

To Yakushima

|

|---|

Three days later we were on a familiar 16-passenger 4-engine DeHaviland, flying from Kagoshima to Yakushima. Our friend in Kagoshima, Mr. Tsumagari, had been working on the trip for over a year, but plans had come apart because of a recent change in Yakushima Forestry administration. An overnight stay in the town of Anbo became necessary, but we met some people so enjoyable that we look forward to seeing them during future Yaku visits: one of Mr. Tsumagari's close friends from his years as a Forestry officer on Yakushima; a self-sustaining and non-denominational Christian missionary; a town official who is the leading authority on Yakushima mountain climbing; a prominent M.D., with a beautiful ocean-side garden, who has joined the A.R.S. (Seattle Chapter).

The next morning, at Forestry headquarters, the climate had changed completely. Tents and sleeping bags were quickly produced, the Forestry Chief presented an excellent map as his personal gift, and we raced out for 3 wild hours of food-buying, packing, and and finding some people to help carry our load up 10 miles of mountain trail. Finally we boarded the little diesel powered train and chugged up the gorge to the mountain town of Kosugidani, where the inn was as comfortable as in 1965. Mr. Tsumagari suggested a before-dinner walk along the gorge and showed us "his garden" of boyhood days: plants of the rich-colored Yaku variant of R. kaempferi , formerly called R. yakuinsulare , and known in Japan as the YAKUSHIMA-YAMATSUTSUJI. Within the gorge, this plant grows from the high mountains nearly to the sea. Mostly it is found among rocks below flood level, and we only saw one wild plant actually growing above the rim of the gorge. Truly a river-bank dweller!

The next morning, the roar on the roof was indeed rain, said to be a Yaku specialty. Nine hours later and 1000 meters higher, it roared as loudly on our tents, pitched just below the 1700 meter (5577 foot) pass between Mt. Kuromi and Mt. Miyanoura. En route, we had been slightly tempted by the idea of stopping at Hananoego, the swampy area at 1600 m. where all of Yakushima's mountain trails come together. This seems to have been the highest point visited by most earlier parties of foreign plantsmen, and it is excellent for a bog specialist but isn't much of a place for students of Rhododendrons and other shrubs. Therefore we went on another 40 minutes to the Kuromi-Miyanoura gap, which had looked good to me from the summit of Kuromi in 1965.

The weather on the way up had been wet and windy but not really a tempest, and we had been much interested in our surroundings. As soon as we reached uncut forest, at about 1200 meters, we started to see the famous Rhododendron of this island. The lowest-elevation ones had thin indumentum on their (usually) large leaves; but, beginning at 1375 m. or lower, plants with light indumentum and plants with heavy, spongy indumentum were growing side by side. Still higher, those with thick indumentum were the more numerous, but lightly-indumented specimens were reasonably common even up to the high ridges and were later seen in quantity at 1700 m. This raises the question of one variety or two: Should all these plants be considered as R. metternichii var. yakushimanum , or should some be split off as a separate var. intermedium ? (The two Japanese names are YAKUSHIMA-SHAKUNAGE and USUGE-YAKUSHIMA-SHAKUNAGE, the "usuge" implying thin clothing.)

This question we cannot answer. We are much interested in the fact that there are lightly and heavily indumented plants and that the two sorts grow side by side. Also, we think it is important to try to explain why this happens. However, we have given less attention to the question of proper nomenclature and therefore continue to call both kinds by the abbreviated Japanese name we always use in our own garden: "Yaku-shakunage."

We noticed that the low-elevation specimens of this plant were particular as to growing site, preferring steep and fairly open parts of the gorge. To our dismay, we found no flowers, and most buds appeared still quite tight.

As for other Rhododendrons, the tashiroi (SAKURA-TSUTSUJI) had finished blooming at Kosugi-dani, but we climbed past plants at their peak of ivory-pink beauty and eventually reached ones which were just opening their buds. At Kurume, we had admired a plant with a single flower, but here they were great, dense bushes 2-3 meters tall, loaded with flowers. A single specimen of R. keiskei , with pink stamens and bright yellow flowers, grew beside the trail. And, when Mr. and Mrs. Berg descended 2 days later in good weather, they noticed where the rest of these were hiding: Large numbers were perched in the Cryptomeria trees, growing from knot holes, broken tops and rough bark as epiphytes. The final species to appear was a purple-flowered Azalea of the MITSUBA (3-leaf) group, which the first noticed as the crossed a rim onto more open terrain at about 1500 meters.

After a damp night in our tents the got up in clearing weather: a break for the Bergs since this was their single full day in the high country. The first venture, of course, was to climb Mt. Miyanoura, the highest peak on the island. Going up from camp a short distance to the top of the pass and then along the west side of the Miyanoura ridge, the salt- many plants of the attractive purple Azalea but hurried on-still finding no really open flowers of Yaku-shakunage, and we were beginning to despair. However, at about 1750 meters, we started to see flowers on a parallel ridge, then they were scattered around us and finally were beside the trail. From 1800 m. to 1860 m. perhaps 10-15% of the total number of plants were in bloom, and this was enough for a good show. (Fig. 33).

|

|

|---|---|

FIG. 33. Rhododendrons among dwarf bamboo near summit of Mt. Miyanoura. Deep hole in front of largest plant had just been discovered by Mrs. Doleshy. Photo by Frank Doleshy |

FIG. 34. A design feature for your garden, close to the summit of highest mountain in Yakushima. Photo by Frank Doleshy |

On the bald terrain at the top of Miyanoura the Shakunage was absent. However, the turf was full of a tiny, white-flowered Yaku violet, of which a large plant would cover a 25 cents piece, as well as

Oxalis

and other flowers. The Bergs spent as much time here as they felt they could afford, then rushed south to climb Mt. Kuromi. We descended more slowly and, among other things, found a Gentian much smaller than the published dimensions of the famous dwarf species native to Yakushima only. Also, the found the most magnificent plant of Yaku-shakunage we've ever seen, growing at the lower edge of a huge plate of granite and spreading its flowers over the flat surface (Fig. 34).

Early the next morning, May 22nd, the Bergs left for the bright lights of Hong Kong and way points, and our friend Mr. Tsumagari accompanied them down. Also, knowing Mrs. Doleshy and me to be familiar with the place and perfectly safe, he went back to Kagoshima and his work, leaving us by ourselves until his return on the 29th.

In peaceful solitude, we had another cup of coffee and decided that the old song, "Stranger in Paradise", more or less described us, except that no Arabian traveler could ever glance back and forth at a scene like the north wall of Kuromi and the south ridge of Miyanoura. Our camp site was not only a base but was a good location for much of our planned program of studying the higher-elevation plants. In other words, we were "there", and didn't have to trek to plants. We had also intended to go part way down the mountain range at several places to see Yaku-shakunage at its lower limits of elevation. However, this plan had been based on the idea that 1500 meters was generally the limit. By now we had seen for ourselves that they grow as low as 1200 m. and had heard of good, mountain-type plants at 940 m. and others down to 600 m. These latter were more than 1000 m. (3300 feet) below our camp, and we decided to concentrate on opportunities at hand, leaving the low-level studies for subsequent visits.

A day-by-day account would be tiresome, since we did a lot of backtracking in order to duplicate and confirm any interesting observation. Therefore, I'll try to give a condensed summary of the way things looked to us.

Yakushima, the Environment

Certain environmental factors are important both to man and Rhododendrons, but man is also interested in being able to tour around. The numerous Yaku trails are properly designed but, with frequent storms dumping immense quantities of water, many stretches turn into streams or giant staircases. Off-the-trail travel below 1700 m. is usually difficult, with Rhododendron, Pieris, etc. forming a barrier like a bedspring, but there are pleasant areas of open woodland. (At one amazing place, the trees were 7 meter-tall Yaku-shakunage,

Trochodendron

and

Daphniphyllum

, with virtually no underbrush.) Above 1675 or 1700m. are rocky or grassy ridges, offering easy off-the-trail travel except when the wind is strong. Above 1800 m. or so, the main impediment is the dwarf bamboo, with stubble that goes through socks and skin. Trails are well marked, in Japanese, and the various worth-while maps are entirely in Japanese. Foot traffic, even on the main N-S trail along the mountain chain, was not heavy and perhaps averaged 2 persons per day (except on the day of the Junior High Schools' annual Rhododendron-viewing hike). Visitors were from many parts of Japan; several accepted us as the only available (temporary) natives of these mountains and relied on our directions.

As for environmental factors of interest both to plant and to man, 11 days of mountain weather included 3 very wet, 3 fair, and 5 mixed, with some rain. During the storms, our thermometer (with bulb either wet or dry) read from 56° to 62°F. During fair weather, morning temperatures were usually in the high 40s, rising into the 60s by late afternoon. We understand that our weather was about average. But, a year earlier on almost the same dates, Mr. Yamawaki, of the Makino Botanic Garden, had 12 rainless days! At elevations around 1750 m., Mr. Tsumagari said, snow accumulates to depths of 2-3 m. and is on the ground from November to March.

The "normal" date of best flower viewing is said to be May 25th (see color). In spite of a cold winter, May 26th could probably be called the top day for 1970, indicating that there is some response to day length. However, this cannot be the sole factor, because the May 25th day length on Yaku is about 13 hours 53 minutes, and this length is attained at Seattle about April 19th and Portland about April 22nd, with no flowers yet open on cultivated specimens of this plant.

|

|---|

FIG. 35. Exposed granite and slight obstruction of wind; an ideal rhododendron site. Photo by Frank Doleshy |

An environmental factor of particular interest to the plants is the rooting medium. Roughly 75% of Yaku Island is granite or granite-derived soil (often, granite granules with little else). Most of the Yaku-shakunage is rooted in these materials, which are not noted for high release of nutrients but usually provide good drainage and upward flow of water vapor (Fig. 35). However, in the lush Rhododendron zone from 1400-1650 meters elevation, plants are also seen growing from moss at the base of tree trunks, from decayed spots in foot logs over streams, etc. Also, at about 1700 m., we saw fairly normal-looking plants in sphagnum bog, with pools of water close enough to be over the roots. (Water in such a bog may have little more available nutrients than rainwater.)

The environmental factor which undoubtedly has the most to do with limits of distribution is the wind. Without high winds, the mountains would probably be tree-covered practically to the summits, with much-reduced opportunities for Rhododendrons. Yet, on exposed ridges, these plants are close to their limits of tolerance and either very compact or, in some cases (probably where previous shelter was lost) have long, stringy, half-dead stems with the last 1 or 2 leaves apparently about to blow off. In extreme sites, as at the top of the pass just above our camp, near-level areas are kept bare by the frequent pounding of wind and wind-borne water, and neither soil nor lichens are seen on the granite. However, a slight dip, not deep enough to shelter a standing person, will break the airflow enough to make conditions tolerable for plants; Rhododendrons, as well as Pieris, Cornus , dwarf Alnus, Buxus, Juniperus , etc. will be as lush as if cultivated-but not very tall.

At highest elevations, especially near the summit of Miyanoura, the dwarf alpine bamboo probably helps set the distribution limit by vigorously occupying areas of deeper soil. But this plant, also, seems unable to survive in the real wind funnels and gives way to a low turf. Cold and snow are apparently no problem to the Yaku-shakunage, and, if a tower 1000 meters tall were built on the highest peak, this plant would probably grow very well at the top (if wind shelter were provided).

Lower limits are doubtless set by competition in the warm-temperature or sub-tropical forest, and the plants we saw at about 1200 m. suffered from over shading. Temperatures on the Yaku coastal plain are apparently near the limits of tolerance. To grow the plant there requires special effort, and we saw one which had been brought down by stages, remaining at Kosugidani for 5 years. As mentioned, we were (and are) interested in the lower limits. But, with respect to these, our 1675 m. camp was like a room on the 100th floor of a hotel, with no way to the action on the streets except by climbing down the fire escape.

Yaku-shakunage: Variation

The important thing to keep in mind is that there are 2 reasons why the plants don't all look alike: First, there is genetic (or true) variation, seen when 2 plants, side-by-side in the same conditions, have different indumentum, different flower color, or other things not alike. Second, there are the differences which simply result from environment. Two genetically identical plants, one in shade and one in sun, will grow differently, and such differences can even be seen on branches of the same plant. These environmental differences, of course, are not inherited, and they are subject to change as the environment changes.

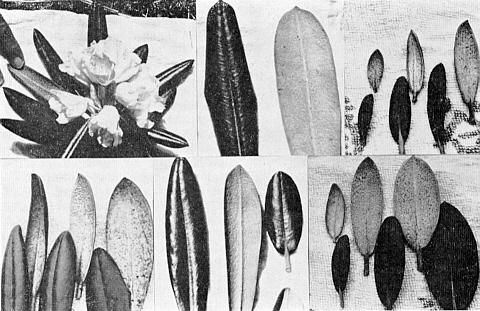

Genetic variation in the Yaku-shakunage is well known and generally accepted (possibly even a little bit exaggerated). The only point which may need further emphasis is that the differences can be seen side-by-side in the wild. One plant may have thin indumentum and its neighbor thick; the leaves on one plant may be broadest at the middle, those on another one broadest near the tip, and those on a third plant much smaller and more pointed; and the colors of flowers and buds in a single field will often vary considerably (Fig. 36).

|

|---|

Fig. 36. Leaves from metternichii var. yakushimanum ; a sample from elevations of 1475-1725 meters, along the high central ridge. In this composite picture the individual photos are enlarged or reduced to approximately equal scale. Photo by Frank Doleshy . |

This high degree of inborn diversity can perhaps be explained as follows: The plant occurs from a low elevation of 600 meters to a high elevation of 1900 meters, a range of 1300 meters or 4265 feet! In this great vertical spread, it tends to segregate into strains with thin indumentum and other low-elevation characteristics, or thick indumentum and other high-elevation characteristics. But, because of close proximity of the low and high country and the frequent occurrence of storms which can easily carry seed, capsules, pollen, or pollen-carrying insects from low to high or vice versa, there is continual stirring of the pot. Also, the relocated individuals seem to be able to survive and compete very well, apparently because the low-elevation and high-elevation characteristics don't really have much adaptive importance (i.e., don't have much effect on survival in a particular environment). As a result, there is diversity at every location.*

*Readers interested in adaptive and non-adaptive variation are urged to pursue this subject in Arthur Cronquist, The Evolution and Classification of Flowering Plants (New York, Houghton Mifflin, 1968).

Besides this genetic variation, and sometimes masking it, is a tremendous ability to respond to differences in the environment. One good place to see this is at the top of Mt. Kuromi, with its summit ridge and summit block crosswise to the prevailing wind. As one leaves sheltered woodland for the open slopes, big plants with stems 25 cm. in diameter are suddenly replaced by knee-high specimens. Also, going from the south to the north side of the summit block, there is replacement of dense, contorted plants by husky, large-leaved ones which would look at home in woods 500 meters lower. (These were the plants which, in 1965, gave me the mistaken idea that R. brachycarpum might grow here, since it was hard to believe in such large plants of Yaku-shakunage just under a major summit.)

|

|

|---|

Flower parts alone appear to be relatively constant genetically-and usually almost immune to environmental effect. Their notably consistent feature is the campanulate shape of the corolla (Fig. 37). Quality of flowers on almost every plant is very high; indeed, so high that a person who grows a batch of seed collected in the wild can reasonably expect to get several plants which will please him more than any existing award form.

Yakushima: Other Rhododendrons

We were very fortunate to arrive during the blooming period of the purple-flowered 3-leaved Azalea (Fig. 38 and color).

|

|

|---|

Proper identification of this plant has proved remarkably difficult, but it is surely either R. reticulatum or R. nudipes , probably the latter. It is a staunch plant indeed; on slopes where wind reduces the Yaku-shakunage and Juniper to low mounds, this Azalea grows as a shapely, small tree, 2-3 meters tall, covered with flowers. These are variable in color, but it is the leaves which vary to a startling degree; on some specimens they were the plum color of Copper-Beech leaves, with the added feature of golden hairs.

R. keiskei , as mentioned, was seen once beside the trail while we climbed through woods, and was later noted in the same area growing epiphytically. In addition, on the Kuromi summit, the form which reputedly stays low in cultivation was in bloom. We found it growing some distance down the west ridge of this mountain. Also, we searched for it on the 1734 meter peak 3.1 airline kilometers to the south and found the same strain or a very similar one on near-vertical granite.

R. tashiroi was at its best near camp as we left (May 30th). This is as generous with its flowers as any other Azalea, but these flowers are of incomparable delicacy, both in shape and color. Color appears to vary with elevation, deeper pinks being more frequent below 1400 meters.