QBARS - v26n2 Trip to Tranquility

TRIP TO TRANQUILITY

Britt and Jean Smith, Kent, Washington

INTRODUCTION

This chronology of a trip to Sikkim was to have been a story of searching for and photographing rhododendrons in Himalaya. Unfortunately the tension which prevailed along the border of Sikkim and Tibet caused extreme restriction of travel in Sikkim. A few rhododendrons were seen growing in and near towns which we visited, but only rarely was one in bloom because it was not their season. As a result of this, the story is mostly of Himalayan people whom we met.

Perhaps our fondness for rhododendrons can help us acquire some of the Himalayan philosophy of life. Perhaps it is even a sign that we are reincarnations of Himalayan people. That can be a pleasant, soothing thought if you care to contemplate on it. Belief in reincarnation definitely contributes to the peace of mind of the Himalayan people. They are a quiet and peaceful, but at the same time friendly and interesting people. Their austere lives are lives of happiness and tranquility seemingly found only where the frantic urgency of the modern world has not yet invaded.

|

| FIG. 30. Tse Ten Tashi holding branch of R. dalhousiae . |

On May 16, 1968, Mr. K. C. Pradhan (who was then living in New Haven, Conn.) wrote a letter to Mr. H. L. Larson of Tacoma. In this letter he stated that he was planning to be in Tacoma the following month and would visit Mr. Larson at that time. He also mentioned that Mr. Tse Ten Tashi of Gangtok, Sikkim was a friend and an ardent naturalist in the Himalayas.

Since Mr. Pradhan's routing for his return to Sikkim did not take him through Tacoma, Mr. Larson gave me a copy of the letter so that I could resume the correspondence if I wished to do so. The primary subject being considered in the letter was the possible procurement of rhododendron seeds from Sikkim, and I was interested in seeds.

By July, Mr. Pradhan's location was not known, so a letter was sent to Mr. Tse Ten Tashi, Gangtok, Sikkim. It was not known if the address was sufficient, if Mr. Tashi would respond, nor how a letter would get to Sikkim. In the letter was an explanation of the exploration that Dr. Frank Mossman and I had done among R. occidentale and of our conviction that the variation found in that species is not restricted to that species. Mr. Tashi was asked if he knew of anyone who would be interested in searching their native species for superior forms of rhododendrons, marking and pollinating the selected plants, and returning later to collect the seed.

In October a letter arrived stating, "Having failed to hear from you, I am again writing to you as advised by Mr. Pradhan, who is now here with us." Later in the letter Mr. Tashi wrote, "I am an orchid specialist, having grown them for the last 39 years, and am 58 years old but still active and young as a youth of 25 years old." Also he wrote, "I shall be in the best position to take the job you had offered, both in collection of the seeds and also take both 35 mm Kodachrome and 16 mm cine colours if need be so that you have the vision of the variations which I have been observing in the past years."

An exchange of letters was devoted to sparring for a price, which was finally established at $500 for the year's effort of hunting, collecting and photographing. This was more than I was able to pay so, at the suggestion of Bob Badger, members of the Seattle Study Club and the Tacoma Study Club were asked if they were interested in participating. The Seattle Study Club, with the urging of Jim Caperci, offered to contribute $200, and before the group dispersed that evening, several individuals contributed more than $100 additional. Since I wished to participate, only $100 interest was offered to the Tacoma Study Club and the members quickly voted to contribute this. The Seeds from Sikkim venture was launched with surprising rapidity.

On February 20, 1969 a letter was written to Mr. Tashi to advise him that finances had been arranged.

Seed soon came from a supply which Mr. Tashi had on hand, and this distributed among the contributors. There was a rapid series of letters both ways, as the banks were very slow in transferring funds to Mr. Tashi's account. On April 24 he finally received notice that the funds had arrived, and all was joy in Gangtok!

Contact was made with the Seattle Rock Garden Society per Mr. Tashi's suggestion that he might collect seed for them. Mr. Tashi's second daughter had been married in Gangtok, and life in general continued at its usual pace.

That is how the Sikkim experience began...

There are three questions which are most frequently asked about Sikkim and which seemingly could most appropriately be answered at this point: 1. What is Sikkim? 2. Where is Sikkim? 3. Isn't that the country in which the American girl married the King? Those questions will be answered in that order.

- Sikkim is a kingdom populated by less than 200,000 people. It is approximately 70 miles long north to south, and approximately 40 miles wide east to west.

- It is in Himalaya, located between Nepal on the west, Bhutan on the east, India on the south, and Tibet on the north.

- Miss Hope Cooke married the Crown Prince of Sikkim in 1963 and became the Gyalmo (Queen) in 1965, when Palden Thondup Namgyal became Chokyal (King) following the death of his father.

Early in our correspondence with Mr. Tashi, we mentioned that the possibility of our traveling to Sikkim to visit Gangtok, to visit Mr. Tashi, and perhaps to visit some of the rhododendrons there. Plans for that trip developed steadily. It was finally decided that we would visit Himalaya in April of 1970. Then there were passports to obtain, inoculations for almost everything (since we would be traveling through Southeast Asia), airline reservations, hotel reservations and, most important of all, the application for a permit to enter Sikkim. Application for this permit must be started about three months ahead of departure date by writing to the Consulate General of India in San Francisco. This office is most responsive and helpful, but India is far away and governments are cumbersome. At almost the last minute we learned that we would be in Indian territory long enough to need a visa, and this caused a small panic - but the Consulate General's office responded quickly and the visa was provided in adequate time.

A short time before the departure date, a shipment of color slides arrived from Mr. Tashi, enclosed with a shipment of seeds. There were approximately 40 species represented, and each packet of seed was to be divided five ways. It is great to have friends at a time like this, and Marge and Bob Badger undertook the big job of dividing and distributing the seed. The pictures went back to Sikkim with us so Mr. Tashi could identify them for us.

The departure date arrived and still no permit to enter Sikkim, so a frantic letter went to the Consulate General in San Francisco to tell of our itinerary so the permit could be forwarded. We had decided that we would go to Darjeeling and Mr. Tashi could meet us there, and that we could have an enjoyable trip even if we did not get to Sikkim.

Our route was through Los Angeles, Honolulu, Guam, Taipei, Hong Kong, Bangkok, and Calcutta. In Calcutta we had a moment of concern when an Immigration official told us that we could not go to Darjeeling without a special permit. It was late at night and we were scheduled to depart early the next morning. Someone said that it would be necessary to apply in Calcutta and wait for two or three days to obtain the permit. At that time a friendly representative of the Department of Tourism arrived to assure us that the permit would be readily available at our next stop. He also helped us get to our hotel, change money, send a telegram, and then appeared at the airport early the next morning to assure us and to see that we found our airplane. For all this helpfulness, he refused any payment!

By seven o'clock in the morning we were headed north in an old DC-3 for what was to me the most comfortable and interesting flight of the trip. The seats were far enough apart and high enough that a fellow who is 6 feet 2 inches tall can stretch his legs to rest them and to restore circulation. The flight altitude was low enough that we had an excellent view of the plains of India. Like so many things about which one reads, the descriptions do not convey the same impact as the experience. The thing that impressed me with the flatness of those plains is the way the streams have changed their courses. From six or eight thousand feet one can see the abandoned river courses by patterns of vegetation and color of the soil. It seemed that the streams have changed courses so many times that at one time or another every square foot of the plain must have been under the water of those streams. The plains of Kansas are rolling hills by comparison.

After a breakfast which was excellent and our first experience with food in India, and a reasonable time to absorb the sights from aloft, we landed in Bagdogra, an Indian Air Force base approximately 350 miles north of Calcutta. Just as the representative of the Department of Tourism had told us, the permit to go to Darjeeling was readily obtained at the airport. Efforts to make reservations for the return flight to Calcutta and on to Bombay, where we would rejoin TWA, were fruitless. We were told to make those reservations in Darjeeling.

Probably 45 minutes had passed since our plane had landed, and we were about to have our first experience with the spontaneous friendliness of the natives of Himalaya. All other incoming passengers had left the terminal while we were obtaining our permit and attempting to make reservations. The next problem was to get to Darjeeling, and this was done by hiring a car and driver for the three hour drive. We had made no advance arrangements and so began inquiring about a car. We were told that one was waiting for us - a pleasant surprise! People in the terminal directed us to a car waiting outside in the shade of a tree - it was the car chartered by a Himalayan lady who had recognized our situation and kept her driver waiting for fully half an hour! She had been an amah to a British family in London for 20 years, the children had grown and left home, and now she was returning to her native Darjeeling. We were to be her guests for the trip up into the mountains and to Darjeeling she would have it no other way.

At the Central Hotel in Darjeeling, we were warmly greeted by the manager and by the proprietor and his wife. It was two o'clock in the afternoon, so they provided us a special lunch and asked if there was any particular reason that we had come to Darjeeling. Yes, there was a special reason; we had come to see rhododendrons growing in their native habitat. "Rhododendrons grow all around the mall", they told us, and pointed the way. As soon as we had eaten, we set out for the mall, all excited over the prospect of seeing Himalayan rhododendrons growing there.

As we were eating dinner that evening, Mr. Madan, the proprietor, asked if we had found any rhododendrons. Not only had we failed to find rhododendrons, we had not found the mall. Mr. Madan assured us that a few rhododendrons must be in bloom because he had seen some children with flowers. The next day, armed with better directions and a little more knowledge of finding our way, we set out again. That evening we were able to report that we had found the mall, which is a paved road around a hilltop rather than a large open area as we had expected. We received further assurances that rhododendrons grow "all around the mall".

On our third day of searching, we walked around the mall again, and at one point noticed a tiny fleck of red up in a tree - rhododendrons! We had been walking among rhododendrons all the time, but they were 60 ft. high instead of being shrubs as we had known them at home. You can readily guess that they were R. arboreum and they certainly do grow everywhere in Darjeeling - if one knows enough to look up into the trees.

About the same time we arrived at the Central Hotel in Darjeeling, a small company of Indian motion picture people arrived also. They were friendly, personable people who told us quite a n u m b e r of interesting and useful things about Darjeeling and Gangtok. Among this group was India's greatest movie villain - and he was the most friendly and personable of them all. It was quite a sight to see him leave the hotel to go to a location to photograph a scene in one of the buildings nearby. The others would get in cars and ride away, but he, dressed in rags for the day's acting, would walk up the street surrounded by children and apparently having as much fun with them as they were having being with him.

|

|

|

FIG. 32. Darjeeling woman carrying our

luggage |

FIG. 33. Mt. Kangchendzonga,

28,156 ft. Seen from Darjeeling. |

The Lloyd Botanical Garden in Darjeeling seems halfway down into the valley as one walks down to it, and back up to the hotel. Actually it is about a ten minute walk, but with a considerable change in altitude. The garden is very nicely arranged and contains an excellent collection of native plants, including rhododendrons. Unfortunately no rhododendrons were in bloom when we were there; some had bloomed and others were still in tight bud. One flowering plant attracted our attention. If you can imagine Mahonia aquafolia with beautiful bracts of yellow flowers eight or ten inches long, you are thinking of Mahonia nepalensis .

One day we stopped at the Darjeeling office of the Indian Department of Tourism to gather information about Darjeeling and the area immediately around it. They were most helpful and informative, and Jean suggested impulsively that we ask them about our application for permission to enter Sikkim, since no word had ever come. The young gentleman to whom we were talking listened to our story and then said, "I will dial the office of the Deputy Commissioner of the Darjeeling District, but you must talk to them." He dialed the number and handed me the phone. A lady answered, and I told her the story of the application for a permit. She asked my name and if anyone was traveling with me. I told her that I was Britt Smith and that my wife was with me. With "Just a minute", she put down the phone and was gone for quite some time. When she returned to the phone, she said, "Your name is Britt M. Smith and your passport number is H011517. Your wife's name is Jean Eleanor Smith and her passport number is J1016146. Excitedly I said, "Yes, that is correct; will we be permitted to enter Sikkim?" Her answer was, "When would you like to pick up your permit?" You can imagine our feeling of jubilation. Then it was hurry to telephone Mr. Tashi, hurry to make reservations on the "transport" (jeep), and hurry to the objective of the trip!

The transport leaves at nine in the morning, right after breakfast. It was about nine or ten blocks to the "bus station", so a little lady who weighed about as much carried our eighty and more pounds of luggage on her head as we walked behind. Fortunately someone had suggested that we pay a couple of rupees extra for each of us to ride in the front seat of the jeep. The driver, Jean and I sat in front, and four young Indians of perhaps college age shared the back with a spare wheel and tire and all of the luggage. On the return trip I learned about riding in back - the top is too low to allow one to sit upright. It can cause a stiff neck.

At the appointed hour the jeep departed Darjeeling, bound for Gangtok. Up the hill to Ghum we went, and then down, down, and down. We drove past long rows of Japanese redwood growing along the road, areas thick with bamboo, women carrying firewood toward town, homes of farmers, and then the very large Happy Valley Tea Estate where women were picking tea. As we neared the bottom of this descent from approximately 7,500 feet down to about 600 feet, we came to the viewpoint from which one looks almost straight down 1,200 feet to the confluence of the Rangit and the Testa Rivers. The joining of the clear water of the Rangit and the gray turbid water of the Testa River is most interesting, and was also interesting to the early botanical explorers as they mention it in their writings.

At the village of Testa, our permit to enter Sikkim was checked the first time. After the formality and a short rest (with no restroom!), we resumed the journey by crossing the Testa River via a temporary suspension bridge which takes the place of a reinforced concrete bridge destroyed by a flood two years earlier. No photography was permitted here, probably because the bridge is considered to be of military importance and we were getting very close to territory occupied by Chinese Communists.

Along the bank of the Testa River extensive repairs to the highway were in progress, to restore it after the flood damage. Nearly all the work was done by hand, and we waited several times while the road was made passable for a jeep with four-wheel drive. The highway seems to be properly built, with large rocks first and progressively smaller rocks as the roadbed is built up, with finally a dressing of crushed rock. The crushed rock is broken by women who sit along the road by a rock about the size of a basketball. With a 10 or 12 ounce hammer, they break rocks to the required size, as they sit in the blazing sun, often with a baby wrapped in their clothing. I called them "one woman rock crushers". It is hot and humid there because the elevation is probably only 800 feet. Quite a contrast to Gangtok at 5,000 feet or Darjeeling at 7,000 feet!

At villages along the way our papers were checked three times that day. At about one o'clock we arrived in Singtam, which is probably the transportation hub of Sikkim. The driver went somewhere to eat without saying anything to anyone. We were hungry and thirsty, but did not know where it would be safe to eat or drink. An idea took me to a little fruit and vegetable stand where I displayed a one rupee note (worth approximately fifteen cents) and pointed to a band of bananas. With this, a young fellow came up, picked up a hand of bananas, counted them, and exchanged the dozen bananas for the rupee.

The bananas were in excellent condition, but slightly smaller than we find in our fruit stands. They tasted very good, especially since we were so hungry, but contained a surprise. As I ate my first one, I bit into what seemed to be a rock, It was a seed, about the size of a large kernel of corn, black as coal and hard as stone.

After probably fifteen minutes, the driver returned from wherever he had gone, and we started the climb up the mountains to Gangtok. The climb is rather steep and very crooked. As our altitude increased, the temperature become more attractive to us from the temperate zone. Probably two hours later we were approaching a city which we assumed to be Gangtok, when someone shouted and the driver stopped the jeep - it was Mr. Tse Ten Tashi!

|

|

|||||||

| FIG. 35. Mt. Kangehendzonga, 28,156 ft. | ||||||||

|

||||||||

Mr. Tashi stood before a two story building with a big bouquet of amaryllis in his hand. What a man is this fellow, Tse Ten - even though 60 years of age, he truly has the vigor and enthusiasm of a youth of 25 - and the humor of Bob Hope. Running around in those mountains certainly has been good for him. The way he goes, he should be good for at least another 60 years.

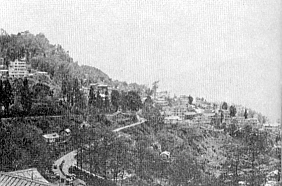

The building was our hotel - two stories high in front and five in back, like so many buildings here. It was not luxurious, but it was adequate and the beds were very comfortable. The view from this Kanchen View Hotel is magnificent.

Mr. Tashi took us to our room and made certain that we were situated satisfactorily, and then asked about our permits. They were for three days. He asked for the permits and left, stating that he would have them extended. By four o'clock he returned, with the permits extended to six days, with two white silk scarves, and with the exciting news that His Majesty, the Chogyal, was expecting us at the palace at six o'clock for cocktails.

The next hour and a half were really something. We were dirty and grimy from the trip to the point that our hair was full of dust and grit. Since the monsoons come during June, July, and August and nearly all of their 90 inches of rain falls during those three months, April is nearing the end of the long dry season. As a result, the only water we had was in a five gallon pail which sat in the bathroom. It takes experience to be able to clean oneself quickly under those circumstances, and this was our first attempt. We combed out most of the grit, knocked most of the dirt from our hands, faces, and ears, and donned clothing more appropriate for our first meeting with royalty.

Tse Ten arrived with a car and driver, and was dressed in his court clothes, which he had worn as a secretary to the father of the present Chogyal. As we headed toward the palace, Tse Ten coached us in proper presentation of the scarves. We had many questions about how does one address royalty and, of course, we became more tense as we came closer to the palace.

At a guard post we alighted from the car for the short walk to the palace entrance, and as we approached the palace, very conspicuous of the scarves rolled and knotted in our hands, it was nearly dark and sprinkling lightly. In the darkness a figure hurried along the broad veranda across the front of the palace, and instead of turning to go inside, turned and came down the steps to meet us. Jean was leading. Tse Ten whispered, "It is His Majesty!"

A scarf is rolled and tied in such a way that with a flick of the wrist it is unrolled and ready for presentation - if one knows how. Jean was all thumbs and excuses, getting hers unrolled while His Majesty waited patiently and said something about some of their customs being awkward. Of course I had time to get ready, so I fared somewhat better. After the really very nice little formality, His Majesty led us inside to the reception room, where he seated us and explained that Her Majesty would join us soon. Some others arrived - an army officer and his wife, a young doctor and his wife, and a young bachelor who was a professional of some kind.

As we sat engaged in pleasant conversation, I was trying to keep my scarf at the ready for Her Majesty's entrance. These scarves are pure white and decorated only by removal of the woof for about one and a half inches near each end. This leaves only warp threads for that distance, and perhaps you can imagine what it would be like to get a button tangled in that. Well, I managed to do it! As I was trying to separate the front of my coat from the scarf, Jean noticed my plight and, concerned that Her Majesty might arrive, just gave the scarf a big yank. Fortunately the thread in the scarf broke instead of the thread holding the button!

Soon after that Her Majesty breezed into the room, and we stood as she walked directly to me. Now it was my turn to be all thumbs. The scarf was very stubborn, the knot most unyielding, and my fingers most disobedient. Finally it was clumsily unfurled and presented. This time Jean had the moment to prepare, so she presented her scarf in the best of form and soon the conversation was resumed.

His Majesty knew that we were interested in rhododendrons, so he discussed them with us. He is most concerned that some species will become extinct because they are cut for firewood. The wood of the rhododendron is so dry that it burns well when it is first cut; thus it is cut even though there are regulations prohibiting it. We talked of the possibility of establishing preserves where rhododendrons could be protected and where superior plants might be collected. His Majesty told us of his radio station with which he works the 14 meter band as a ham. Her Majesty sat with one couple and then another, talking of her interests which are many. It was a most enjoyable conversation with friendly people, who, in a very charming way, make one feel as if he were chatting with his neighbors. Cocktails and hors d'oeuvres were served all the while.

It was good that Tse Ten indicated, at an appropriate moment, that it was time to leave, because it was so interesting and we felt so welcome that it seemed we could talk all night. What delightful, hospitable people!

From the palace we went to the Tashi's home for dinner. For the next four days we were to eat three meals a day there. The food seemed more Chinese than Indian, and we enjoyed it - the Indian food is too spicy to suit our taste for long. The national drink of Sikkim is Chang, which Tse Ten called "bamboo juice". He called it this because it is served in a container about twelve inches tall and three and one-half inches in diameter, which is a section of bamboo. It is drunk through a "straw" which is a thin section of bamboo plugged but slotted at the lower end and thrust clear to the bottom of the container. Chang is damp fermented millet which has been slightly spiced and very lightly smoked. It is served by filling the container in which the "straw" is first inserted completely full of the fermented millet. This millet is an attractive rusty brown color, so it is decorated by sprinkling a few grains of white rice over the top. Over all this, hot water is poured. The hot water leaches the alcohol and flavoring from the fermented millet. The taste is not remote from saki, and of course the effect is exactly the same.

After dinner Mrs. Tashi came in to meet us. She spoke no English, but her warmth penetrated that barrier easily. Tse Ten said that she understands some English. We had expected that she might be a tiny Oriental woman, but she was instead a stately five feet six inches tall. The Tashis were married in Lhasa in 1937, since Mrs. Tashi is Tibetan.

The next morning was cloudy, but between the clouds the air was clear, so we hoped to be able to see Kangchenjunga. We did see it that day, but only the tip is visible in Gangtok. Mr. Tashi arrived at our hotel carrying a spray of orchids approximately 18 inches long. These were taken to the roof of the hotel where we photographed them and the beautiful lilies which Tse Ten had with him when he hailed the jeep as we arrived the day before.

After breakfast at the Tashi home, we visited the monastery which is on a little hilltop right in Gangtok. Here we were introduced to the ritual of walking clockwise three times around a holy place. This monastery was clean, attractive and interesting - but things were happening so fast that not much else really clings to our memory. In the gardens around the monastery were thousands of orchids which seemingly are there largely as a result of Tse Ten's efforts.

Not much time was spent in Gangtok that morning, as we were soon in a jeep bound for the Dharma Chakra Centre at Rumtek. Rumtek is visible from Gangtok; it appears quite close as one views it across the valley, but to reach it requires descending to the floor of the valley and then back up again to Rumtek, which is slightly higher than Gangtok - a considerable trip. Tse Ten made it most enjoyable though by dismissing the driver and his jeep from time to time while we walked along the road. It seemed that our Sikkimese friend knows the scientific name of every plant we saw and every bird we heard. He showed us where the woodcutters were chopping down trees of Rhododendron arbore um, and he showed us many plants which are familiar to us either as garden or house plants.

All of this took place along a narrow and winding but paved road with gentle grades. It passed by beautiful terraced farms where we saw numerous small goats and a few chickens near buildings of reinforced concrete with thatched roofs. It passed through forested areas where many birds were singing and calling. It is nearly always on the side of a steeply sloping mountain, and frequently there were magnificent vistas through the trees, or across a farm to some mountain, or to the other side of the valley.

We visited a monastery which Tse Ten told us is the oldest in Sikkim. It is seemingly deserted, but considerable restoration work is in progress. One building is constructed over a basement on a foundation of stone and mortar. The upper portion is of a framework of small timbers between which the structure is of willow-like twigs woven basket-like and plastered with mortar. This building is about the size of a single car garage, and is in excellent condition though it is estimated to be hundreds of years old. No doubt the thatched roof has been replaced many times. In two or three places the mortar had fallen away to reveal the basket-like structure.

It was here we noticed some R. arboreum florets in a tree which was not tall, although the trunk was large. There appeared to be crotches and branches spaced to make climbing easy, so I climbed the tree and picked the truss. Evidently Tse Ten had never seen an adult climb a tree before because he referred to that incident throughout the remainder of our stay in Himalaya.

Even at this leisurely pace, we arrived at Rumtek and the Dharma Chakra Centre in good time. The monastery is in beautiful condition, as it was completed in 1963 - only seven years earlier. It is said to be, as near as practical, a duplicate of the monastery in Tibet which it replaces. Photographs of this beautiful monastery may be seen in the National Geographic Magazine for November 1970. Tse Ten seemed to be on very friendly terms with all the monks and greeted them with friendly conversation. Before long we had made our way to the third floor and a small room about 10 feet square which seemed to be a sort of waiting room. Mr. Tashi removed his shoes and instructed us to do the same. We did not really know what was taking place.

Soon one of the monks appeared at the doorway and said something to Mr. Tashi. He stepped across the narrow hallway and through a drapery covered doorway directly opposite. We saw him turn left and start to bow as the drapery swung back into place to block our view, but we heard the bump as his knees reached the floor. As soon as he had completed his obeisance, he pushed the drapery aside again and asked us to come in, stating that His Holiness was ready to receive us.

Stepping into that room became one of, if not the most, memorable events of my life. The room is probably forty or fifty feet long and twenty feet wide. There were few furnishings in it, but it is beautiful in its simplicity. The floors are polished and everything is of the highest craftsmanship. Along the full length of the wall to our left are windows, floor to ceiling. There was no other source of light, but the room is excellently lighted. Little else about the room lodged in my memory because all attention was almost immediately focused on Gyalwah Karmapa, the lama we had come to meet. We bowed as we presented our white silk scarves and said, "Good morning, Your Holiness", just as Tse Ten had instructed us. Each scarf was taken in turn by His Holiness and immediately returned. At this point we each felt very much relieved because we had managed to present the scarves in good fashion and without the fumbling of the previous presentations.

Soon we were seated with our backs to the windows, and His Holiness was engaged in happy conversation with Mr. Tashi. How we wished we could speak Tibetan! His Holiness stated through Tse Ten that he felt honored that we had come so far to visit him, and we replied through Tse Ten, our able interpreter, how pleased we were to be there. His Holiness talked at length with Tse Ten, frequently speaking to us through him. They would both talk rapidly and both would chuckle with amusement over their conversation. His Holiness is such a fascinating person that I did not divert my vision from him for a long time, and when I did a strange sensation came over me.

As I looked away from him, I intended to gaze around the room, but my mind did not perceive what my eyes saw. My mind seemed only conscious that His Holiness was concurrently the source of a glowing white light and of an attraction like that of a magnet on a piece of iron. When I looked at His Holiness again he was the same handsome, appealing, smiling, tranquil human that had been sitting there on that wide couch at the end of the room when I looked before. To test myself, I looked away again, and again saw the glow and felt the pull.

This impressed me so that I could not resist telling Tse Ten, who relayed it to His Holiness. I told him in different ways because the telling seemed inadequate to describe what I saw and felt. It was discussed at length and finally dropped from the conversation, though I continued to be conscious of and impressed by the experience.

At one point Tse Ten said, "Come", and His Holiness smilingly nodded that we should go. We were taken out through one of the windows which is also a passage onto the roof of the floor below. At the side of the monastery facing the hill Tse Ten showed us some very special plants which he had planted there, but I have no memory of what they are. After a few minutes in the refreshing cool breeze, we returned to the presence of His Holiness to find tea and some cookies and nuts waiting for us. We really enjoyed these because it had been a long time since breakfast.

After tea we again went out, and this time to the very top of the monastery to see a collection of rare birds. These evidently are the hobby of His Holiness, and every bird is of a beautiful golden color. They varied from small finch-like birds up to one which was maybe twelve inches long. The room in which they are kept is rather dark, but I did manage to get a good photograph of the largest one, a beautiful bird like a small parrot. Each is in its individual cage, and they are taken outside for sunshine and air each day. On the way to resume our audience, I asked Mr. Tashi if it would be permissible for me to ask to photograph His Holiness, to which he replied, "It would be quite appropriate."

When we returned to the presence of His Holiness, Tse Ten told him that we wished to take his photograph. He readily consented to this, but I was disappointed because he assumed a facial expression of somber dignity for the camera, whereas he had been so pleasantly smiling as he talked with us.

As His Holiness sat talking, he was twisting some red and then some green cloth in his fingers. After he had twisted for awhile, he would cut that portion of the cloth from the larger piece, and tie an unusual knot in the middle of it. When three of these had been prepared, Tse Ten bowed before His Holiness and a red one was placed around his neck. It was indicated that Jean should do the same, and a green one was placed around her neck. I was last and received a red one, which I started to tie in front as Tse Ten had done, and Jean followed his example. His Holiness called me back and tied mine for me. Later Tse Ten expressed amazement, first because a scarf had been presented to a female, and secondly because His Holiness called me back and tied mine for me. Tse Ten said that he had not witnessed nor heard of either of these before.

All too soon we took our leave from His Holiness, returned to the little waiting room for our shoes, and departed from this sanctuary of peace and holiness. When we were in the jeep riding toward Gangtok, Mr. Tashi said to me, "We are of the same family." He and His Holiness had decided that my sensations were evidence that I am an incarnation of one of them! It is an intriguing and pleasant thought to me.

We alternately rode and walked as we returned to Gangtok, and Tse Ten showed us more places where the woodcutters had destroyed R. arboreum for firewood. These rhododendrons the Chogyal had told us, do not grow from the roots when they are cut; thus there is concern that they may become extinct.

Tse Ten had told his wife that we would return for lunch at one o'clock that day, but we arrived at four! We ate lunch and then just had time to return to our hotel room, wash, and return to the Tashi's for dinner, to which he had invited his second son.

The following day was Sunday. We visited the Tashi's eldest daughter and her child at their apartment. Near the bazaar, we walked up the hill to visit his second daughter and her husband. They proudly displayed their new baby and served us orange juice - very welcome because the day was warm. All of these people are good looking, charming and hospitable. They speak excellent English and make one wish he could stay in Sikkim for a really extended visit.

Sunday is market day, so we walked through the bazaar which was teeming with people and interesting merchandise. There were interesting pictures everywhere, but we were reluctant to take pictures of people without permission of those being photographed.

Monday morning we visited the palace of the Dowager Queen. The gardens surrounding this Taktse Palace are beautiful, but we were permitted to take no pictures there. There is a very nice greenhouse, and everything shows evidence of a great interest in gardening. The Dowager Queen was indisposed, so we were unable to greet her. Next we went to the Royal Chapel at the palace of the reigning Chogyal. It was in this chapel that the royal wedding was performed and also the coronation. It is a small but regal place, and the repository for many holy Tibetan Buddhist articles. We walked around it three times clockwise before entering, as is the practice at such holy places and is done to bring good fortune. Perhaps it provides other benefits also, such as an ample opportunity to see the exterior, along with fresh air and a constitutional.

The chapel and the Institute of Tibetology immediately adjacent were very interesting, but we were becoming so satiated with things entirely new to us that our memories of these details are poor. Now we want to return so these things can be really appreciated.

We visited the government office building, where we went from office to office to meet the Prime Minister, the Secretary to His Majesty, the Secretary to His Majesty's estate, the Police Commissioner, the Conservator of Forests, and others. Mr. Kessop Pradhan, Conservator of Forests, served us tea and cookies in his office. Indirectly he was responsible for our being there, as it was he who had written to Mr. H. L. Larson. Mr. Pradhan told us more of his stay in the United States and of his activities related to his office in Sikkim. The largest item related to forestry at that time was herbs; the largest item there is cardamom.

Our last day in Sikkim was extremely clear, so we took advantage of the opportunity to photograph Kangchendzonga, which is forty miles away on the Sikkim-Nepal border. It is the third highest mountain in the world, reputably the dome of deities and consequently a holy mountain, and a beautifully impressive peak. In the afternoon we visited the Tibetan Technical Institute for Cottage Industries, where many native crafts are taught. Beautiful gifts made at the Institute can be purchased there, and we took advantage of the opportunity.

In the evening after dinner, Mrs. Tashi appeared with scarves and gifts. Jean received an Indian "jade" necklace, a Tibetan silver ring, and some very special woven cloth which had been presented to Mrs. Tashi by an important lama. She apologized because she only had a Tibetan silver ring and an antique Tibetan jade ring for me. No doubt the jade ring is very old and a family heirloom. I was moved and honored to receive it. The event was a bit trying because Mrs. Tashi wanted so much to talk to us and we to her. Chang flowed freely!

We rose early the next morning, and found it necessary to work to get everything into our bags. When the hotel manager brought our tea, she said it had snowed up an the pass at Natula during the night. We had a quick breakfast with Tse Ten and boarded our jeep for the trip back to Darjeeling. The return trip was as long as the trip in (six hours), but much more interesting with Tse Ten as our guide. At Singtam we had some beer to quench our thirst. At Tista we had beer again and some lunch. Above Tista we stopped at the observation point where one looks down onto the confluence of the Tista and the Rangit Rivers.

Near Ghum (pronounced Goom), only five miles from Darjeeling, Tse Ten spotted R. dalhousiae growing on the hillside above the road. Florets were five inches across and five inches long. They were very fleshy, light yellow in color, and quite fragrant. Leaves were eight inches long by two and one half to three inches broad. Soon after that we saw R. edgeworthii blooming in a garden and obtained permission to pick a branch. Nutmeg fragrance perfumed the area around the plant. The large white florets were beautiful, but had been damaged by rain and hail. Pollen and cuttings were taken for shipment home.

The next morning some Indian fellows from Assam, staying at our hotel, invited us to accompany them as they hired a car for the day. Mr. Tashi was to be busy that day tending to some business matters, so we went. The first stop was the race track at Lebong, and then the Tibetan Refugee Self Help Center nearby. A guide told us that 550 Tibetan refugees live here. They dye wool and spin it into yarn, using spinning wheels developed by Mahatma Ghandi. The yarn is knitted or tied into rugs. Knit items did not appeal to us, but we thought the rugs unusually beautiful. Tibetans do not use rugs as we do, but sleep on them. They are so thick and dense that they must be very practical for that use. Leather goods and wood carvings are also made here. The community kitchen is primitive by our standards, but very clean. Small loaves of bread had just been removed from the big clay oven when we arrived, and some was offered to us - it was excellent.

We visited the processing plant of the Happy Valley Tea Estate. It is a rather large mill-type building with many racks for drying tea. The building is quite rough inside, but clean and orderly. There is much hand work done, but whenever machinery is the efficient means of production, special machines are employed. A native guide escorted us and explained the process throughout.

On April 24 we went to Tiger Hill with Tse Ten as guide. Our quarry was rhododendrons. Plants were frequent but flowers scarce. We found one poor plant of R. lindleyi on which the flowers had been pummeled by rain and hail. Tse Ten showed us Cobra Lillies, which are certainly aptly named, and to us a real curiosity.

At Ghum, Tse Ten and the driver went to the factory to purchase kukris, Ghurka knives, for Jean to give our sons. He said the price would be double if we went along. These are the knives, blade hooked with respect to the handle, which are standard equipment with Ghurka troops and which they use so effectively. The purchase price was slightly over 52.00 each when they were purchased this way.

Nearer Darjeeling, Tse Ten saw R. dalhousiae growing on a hillside above the road. It was very steep as Himalayan hillsides are, but largely grass covered, so we managed to scramble up. There are perhaps three dozen plants in an area two or three hundred feet in diameter, and varied noticeably in quality. The best plants bore trusses of five or six florets, each five inches long by five inches across and very fleshy. Swelling buds were as green as the leaves and remained green until the lobes began to expand, when they faded to a rich creamy yellow. The florets were trumpet shaped and ultimately faded to almost white. Several plants bearing superior trusses were marked in the hope that seed might be available later, and one truss was taken to our hotel. That evening it provided a very attractive fragrance.

Nearer Darjeeling, we called at the home of Mr. Sain, who is an artist and a rhododendron buff. He paints very unusual oil paintings of mountains, frequently with a stream or lake in the foreground. After one looks at one of these pictures, he may suddenly realize that some of the rocks in the water are actual rocks attached to the painting, the rocks are so carefully selected and so skillfully worked into the picture, that the effect is really startling when one realizes what he is seeing.

Mr. Sain has written articles about "Rhododendrons of Darjeeling and Sikkim Himalayas" and presented us with reprints of the first two from the Journal of the Bengal Natural History Society. These are considered precious possessions and will be studied soon for comparisons with the descriptions which are accepted as official by the Royal Horticultural Society and the American Rhododendron Society.

Our visit to Mr. Sain produced the only projector in Darjeeling which was available for us to project the slides of R. occidentale which were with us. That evening we returned to Mr. Sain's home where we spent several very pleasant hours seeing his exceptionally beautiful color slides of rhododendrons of Himalaya, and showing our slides of R. occidentale .

The next day the Darjeeling Flower Show opened. In accord with tradition, Tse Ten Tashi was one of the judges. When we were finally admitted at three o'clock in the afternoon, we were greeted by the spectacle of a large hall about the size of a high school gymnasium, completely filled with floral exhibits. As is so often the case, it was too dark for photography, especially since it was a threatening day with intermittent showers. Flowers exhibited covered about the same range as one would see in a general flower show here. A fairly extensive group of exhibits of cacti indicates the urge for all gardeners to grow things which are foreign to the climate. The cacti were of a wide range of unusual species, and very attractively grown and displayed. Of course orchids were there in great profusion and variety. We were disappointed because R. dalhousiae appeared only twice, and one identified as R. azaleaflorum once - no other rhododendrons.

The flowers which appeared most frequently were lilies. They were spectacular! Lilies are popular in Himalaya and grow very well there. When I asked Tse Ten where bulbs of the beautiful lilies he grew could be purchased, he replied, "They are more available to you than they are to me. The bulbs come from Holland."

We had stayed two extra days in Darjeeling just to see the flower show, and agreed that we were amply rewarded for the extra time.

The next day was a cushion in our schedule, so we felt very relaxed about time. right after lunch, Tse Ten stopped at the hotel with a jeep crammed full of potted orchids which he was taking to Gangtok. These were to decorate the palace in honor of a visiting dignitary from India. We parted company there from someone who had been our companion, host and guide for more than a week. As he drove away, we felt that a very dear friend was leaving, but that surely we would see him again before too long.

That afternoon we took a very long walk to St. Paul's School to see the beautiful and well-known gardens there. It is high above most of Darjeeling, and provided us an outstanding panorama with the beautiful church and more colorful gardens in the foreground, Darjeeling below, and fleeting glimpses of the snows in the background as the clouds hurried by.

We were interested at St. Paul's School to note that they have a problem raising flowers which we do not share. A burlap canopy is installed over their flowers until the middle of May because afternoon hail showers will strip the flowers if they are not protected.

At 3:50 the next morning, the watchman knocked at our door, and when we woke we could hear the very hard rain. By 5:30 we were in our "transport", a four passenger sedan containing six persons, and starting the seeming interminable trip to Bagdoga and the Indian plain. It was still dark and raining hard, but we were pleased for the people of Darjeeling because they had told us that the city reservoir contained only enough water for two more days. The monsoons arrived early and were sorely needed. We were going home and happy to be going there, but already looking forward to returning to Himalaya.