JARS v36n4 - The Propagation of Hybrid Rhododendrons from Stem Cuttings - An Historical Review

The Propagation of Hybrid Rhododendrons from Stem Cuttings - An Historical Review

James S. Wells, Red Bank, NJ

Those of us who now meet a substantial commercial demand for hybrid rhododendrons by propagating a wide range of varieties on their own roots may tend to forget that the methods now used so successfully are of fairly recent origin. In fact, the availability of "own root" plants goes back no further than 1952, at least in substantial commercial quantities, and production prior to that date was almost entirely by grafting, with an occasional grower producing plants of a limited range by layering. This last method of course did produce plants on their own roots, but the requirements for producing a quantity of plants was so onerous that very few growers were equipped or even inclined to attempt layering on any substantial scale.

I should perhaps define here what I mean by hybrid rhododendron. I realize that the name rhododendron officially includes an extremely wide range of species which in turn are to be found growing in almost every climatic zone from arctic tundra to the tropics. There is a range of naturally dwarf, small leaved plants, native to either high altitudes or high latitudes, most of which have always been rooted from cuttings in much the same way as the azalea group. Azaleas as a whole are technically rhododendrons, and in this discussion I am not including any of these groups of plants, botanically rhododendrons, which have all been propagated on their own roots with a substantial measure of success.

I am referring to the large range of varieties known somewhat loosely as "hybrid rhododendrons" which are large leaved, evergreen, and for which the plant known by almost everyone as 'Roseum Elegans' might be considered a typical example. Species with these similar broad-leaved evergreen characteristics could be raised with reasonable success from seed, although some variation in individuals would be inevitable. But where two plants had been purposely crossed to produce a hybrid of selected form and color, then vegetative propagation was essential. Grafting, using R. ponticum as the understock had been adopted worldwide as the most practical and successful method of reproduction. Browsing through some old files the other day, I came upon an article published in March 1928 in the Florists Exchange, which covered in great detail the methods used for the propagation of hybrid rhododendrons in Boskoop, Holland. It is interesting to note that although production was estimated to be in the millions, all were propagated by grafting, and there was no mention of propagation by cuttings of any variety or type.

Yet the knowledge that broad leaved rhododendrons could be rooted had been available for a long time. An early reference that I have found is in a book entitled "The Propagation and Improvement of Cultivated Plants" by F.W. Burbidge which was published in 1875. In this he says, "All species may be propagated by cuttings of young wood just as it gets firm at the base. These should be pricked into pans of sandy soil and placed in a warm frame or pit for a week or so previous to setting them on a gentle bottom heat." He goes on to mention R. caucasicum and 'Cunningham's White'. But although the ability of these two plants in particular was apparently well known at that time, for some reason no effort was made then or later to establish a set of procedures which would produce good rooting, even on those varieties known to be reasonably easy to root. For nearly 55 years growers everywhere were seemingly content to continue with the time honored method of grafting onto R. ponticum .

In 1936, Clement Bowers again states in his book on rhododendrons that 'Cunningham's White' can be rooted with 90% success using a peat sand mixture with bottom heat, and in the same year L.C. Chadwick published results of treating the same variety with permanganate of potash which improved the rooting. We can see therefore that from 1875 and earlier until 1936 there had been little or no advance in the knowledge and understanding of how to root large leaved rhododendrons. But things were now beginning to move.

In the mid 1930's two different and independent lines of approach to the problem developed, the first under the stimulus of the arrival of root inducing chemicals (hormones or auxins as you prefer) and the second from the astuteness and good thinking of one individual Guy Nearing. In these developments the work of Guy Nearing must take pride of place because, during the years immediately prior to 1939, it was he who conceived and developed a method of rooting rhododendrons from cuttings in fair quantities and in a considerable range of varieties.

|

|

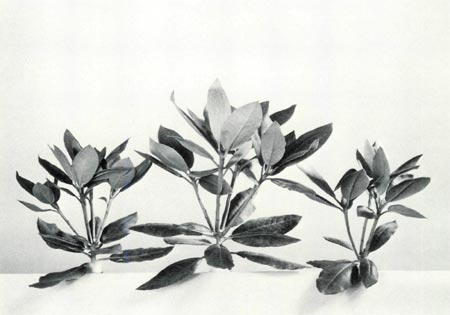

Rhododendron stem cuttings should develop to plants

of this size by the end of the first growing season. photo by James S. Wells |

His method depended upon two things. First, the construction of a special type of frame from which all direct sunlight was excluded, and second, the use of a considerable length of time — a minimum of one year for the more easily rooted varieties and up to two years for the more difficult ones. Although Nearing's work coincided with the advent of root inducing chemicals he did not use these, and in fact specifically stated that under the conditions of his system they were of no value. One of the main factors in the Nearing method was the maintenance of a completely natural environment as far as was possible. Bottom heat was not used, and the only concession Nearing made to "artificiality" was the need to maintain a close, humid atmosphere within the frame to ensure that the cuttings remained turgid. To this end he avoided any rapid changes in temperature by building a baffle which prevented any direct sunlight falling upon the frame and he backed this up by establishing a series of layers under the actual rooting medium, designed to retain and slowly release moisture as needed by the cuttings. During the year 1936 Guy Nearing worked on his system refining it and proving by actual production that rhododendron cuttings could be rooted and that plants on their own roots were just as good if not better than grafted ones. This development work was carried out together with Rutgers University; and in conjunction with Charles H. Connors, Rutgers published a full description of the Nearing method as their bulletin #666. The material was submitted for publication in January 1939 and actually published later that year.

In 1934 the two primary root inducing chemicals, Indole Butyric acid and Napthalene acetic acid, were patented and introduced to the horticultural world by the Boyce Thomson Institute at Yonkers, N.Y. and immediately many people all over the world began testing these chemicals on a wide range of plants. Henry Skinner, then at Cornell University, was in the forefront of this and he published an excellent paper in 1937 detailing experiments he had carried out on rhododendrons and azaleas. He reported good rooting on many varieties, but he then went on to apply a method of propagation that had first been reported in 1934 on the rooting of raspberries and blackberries, namely the use of leaf bud cuttings. Testing this type of cutting together with mallet cuttings he reported in 1939 that he had managed to successfully root many hybrid rhododendrons, and he showed that the production of good plants on their own roots by this method was entirely possible. There were, however, hazards with the leaf bud and mallet cuttings, for the establishment of a sound plant depended completely upon the successful growth of the one bud. The breaking of dormancy in this bud was uneven for at that time the need for a cold period of dormancy to ensure the subsequent development of the bud had not been clearly established. A batch of well rooted leaf bud cuttings might well remain static in part for up to 20 months before some of them finally decided to grow, and sometimes both the leaf and the bud would die before growth could take place. The net result could therefore be patchy and not really suitable for maintaining constant and steady production demanded by the normal wholesale grower.

Coinciding with Skinner's work, a number of other people had begun to apply the new root inducing chemicals to a wide range of plants, which naturally included rhododendrons. Hitchcock and Zimmerman at Boyce Thomson were among the first and they published papers in 1937 and 1939 showing that broad leaved hybrid rhododendrons responded to these chemicals and could be rooted. Kirkpatrick, also working at the Boyce Thomson Institute reported in an article in the American Nurseryman, published in 1940, that quite a number of the named hybrids could be successfully rooted if the cuttings were taken in September, October or November and treated with IBA. Much of this work was repeated and confirmed by Doran in 1941 who published quite a substantial bulletin, #382, of the Massachusetts State College at Amherst, Mass. In almost all of these reports the suggested rooting medium was 50% peat and 50% sharp sand.

It is interesting to note that, as we thread our way through the slow development of rooting techniques, at no time up to 1941 is there any mention of wounding the cuttings or using any form of controlled watering or humidification. These additions to the spectrum of procedures now generally in use on rhododendrons and many other plants had not been considered or applied by any of the people working on the problems of rooting. The control of water loss had of course been recognized as a major factor in the successful propagation of almost any plant by any method, and the construction and management of a greenhouse was designed to limit water loss to the minimum. What was not understood was that even in a well constructed and managed greenhouse, variations in temperature which could be quite rapid as the sun rose on a fine day could result in an equally rapid change in humidity. If, let us say, a greenhouse with open benches filled with cuttings and well damped down was at 100% humidity at 4 a.m. in the morning while it was still dark, the same house could drop to 80% humidity or even lower within 15 minutes of the sun rising above the horizon. Sunrise might well be at 6:30 in the morning, perhaps an hour or more before the grower would enter the greenhouse at the beginning of the day's work. The cuttings could therefore have been under conditions of considerably lower humidity for perhaps 2 hours; and although the plant material might appear turgid and in good condition, water loss from the leaves of the cuttings was inevitable. Much later Kemp, working at the Edinburgh Botanical Gardens, showed that once a cutting or graft had lost water in this way, it was extremely difficult if not impossible for the plant material to regain this lost water. Therefore it continued to suffer from a water deficit, which although not readily noticeable, had a most damaging effect upon the final results.

The controlled use of water and the semi-automatic application of a spray of water, either as a finely divided mist or as an actual watering, was first used by an Englishman named Evans who was working in Trinidad on the rooting of Cacao cuttings. He reported his results in a paper published in 1936 and he showed that regular automatic applications of water greatly improved results. In the beginning he applied water to the outside of the propagating frames to keep the propagation area both cool and uniformly moist, but it was quickly realized that the direct application of water to the cuttings was even better. A system was devised in this country using water and compressed air to atomize and disperse it. The system worked well but was fairly costly to install and because of this did not gain immediate favor. However, the use of controlled and regular applications of water in various forms was tried by a number of growers in 1939 and 1940, and the results were published in articles in The American Nurseryman.

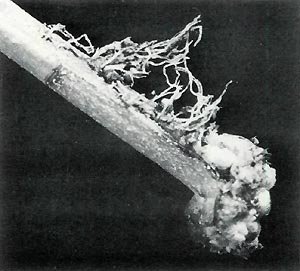

|

|

Effect of single heavy wound showing

roots emerging from the wound. photo by James S. Wells |

Wounding as an aid to rooting was, at this time, little known and as far as I can tell no commercial grower used this technique before the war. The earliest reference I can find for this practice is a paper published by The American Society of Horticultural Science by Leonard H. Day in 1932. He reported on three types of wound. 1.) The removal of a thin slice on one side of the base of the cutting for a distance of about two inches, 2.) The splitting of the bark in four places with the point of a knife blade, and 3.) The scraping away of most of the bark from the bottom two inches of the cutting. He showed that the removal of the single slice was the best type of wound and that the others were less satisfactory. His tests were made primarily to determine whether the application of a wound helped the un-rooted cutting absorb water from the medium in which it was placed, and he concluded that wounding did have this effect. He then went on to test the theory that a wounded cutting treated with any finely divided powder could absorb needed water from the medium with even greater efficiency. He found that coating the wounded base of the cutting with a clay paste or finely powdered carbonate of lime clearly helped the cuttings establish a close connection with the fine layer of water — the hygroscopic layer — present around every particle of the medium, and thus to absorb from this source additional water as needed to keep the cutting in good condition. This most valuable piece of work seems to have gone almost unnoticed for some time, for it is not until 1938 that Stuart and Marth reported improved rooting on cuttings of Ilex opaca that had been wounded. At about this time the same effect was noted on hardwood cuttings of grapes and in 1941 L.C. Chadwick and J.C. Swartley also reported on the use of a wound in conjunction with the use of auxins.

The spread of the European war to include America at this time effectively halted any further work and with this break in the sequence of events I would like to take you back to about 1935 and explain briefly how I became involved in the problem. In 1935, working for my father in his nursery I first became interested in propagation, mainly in connection with the production of alpine plants, which we produced in quantity. Knowledge of the recently introduced root forming chemicals had just become available and I commenced experiments with liquid formulations of both IBA and NAA.

When war broke out we all had to switch to food production, and about this time I commenced my own business, growing mountains of radishes and tons of tomatoes, while still maintaining in a discreet corner a few plants of greater interest. Sometime in 1943 the first American troops appeared in our area and we were glad to offer them hospitality in our home. As a result someone brought a magazine containing an article about The Seabrook Farms Co. at Bridgeton, N.J., which I read and with little thought of the possible results I wrote to Mr. Seabrook — this must have been some time in 1944 — telling him who I was, what I could do, and asking if he might have an opening somewhere in his organization. Four months later I received a reply saying that he owned a nursery, Koster's Nursery, which specialized in rhododendrons and azaleas which he would wish to rebuild as soon as the war was over. Would I be interested? Of course I was.

With the war finally over, early in 1946, I obtained a passage on a freighter to the U.S. to see for myself, and returned home a month later with my position of manager confirmed, and a clear understanding of the magnitude of the job which I had undertaken. Realizing that expertise in radishes, tomatoes and alpines was of little value, I decided on a trip to Boskoop, Holland, to learn at first hand how they were propagating rhododendrons. A friend offered to put me up and I spent four exciting and instructive days in that horticultural "mecca".

But it was on the last day of my visit that I really hit the jackpot for on this day I went to the Boskoop Trial grounds. This experimental station which flourishes now, as then, right in the center of Boskoop, tests and evaluates new plants and new methods of production on an enormous range of ornamental plant material. While being most scientific in all that they do, they are at the same time essentially practical in their approach.

I was conducted round by a Miss De Boer who had sufficient knowledge of English to explain what was going on, and I realized very quickly that here was an endless and almost bewildering amount of information. I learned also that their work had been printed in annual reports since 1941 and that any bona fide nurseryman could join the association and obtain the year books if he wished. You can be sure that I joined on the spot, and purchased the full set of year books.

It was on this day, talking to Miss De Boer and later browsing through the year books that I heard and read of the practice of wounding as an aid to rooting. Not only were the percentages of rooted cuttings much higher, but the quality of the root systems was greatly improved. I spent the balance of the summer translating one of the latest year books into English and as this progressed a number of factors became increasingly clear. Timing was of the utmost importance, and with some plants quite critical. The correct medium was important, the proportion of peat to sand altering results substantially. But again and again wounding was shown to be of great value, particularly when coupled with a hormone treatment. This was shown to be true on a wide range of plants including junipers, magnolias, acers and particularly on rhododendrons.

It is interesting to record however, that although the Boskoop Trial Grounds were successfully rooting a number of hybrid rhododendrons at this time, it was to take another ten years before the practice came into use on a significant commercial scale by the local growers. Nurserymen the world over, it seems, are slow to change.

The last week in August 1946 saw us fly out from England to start a new life, and within six weeks of landing in Bridgeton I had a well rooted batch of Magnolia soulangeana cuttings ready to pot on. This in itself was startling to the old dutch propagator, and when I suggested that it might be possible to root rhododendrons he said, quite flatly, that it was impossible. I thought otherwise, but it was too late to initiate tests that year, so trials would have to wait until 1947.

After the war I undertook to assemble all possible published information on the rooting of rhododendron cuttings that I could find. When brought together and added to that which I already had from Boskoop it made quite a formidable pile.

First and foremost was the work already mentioned of Guy Nearing. Then followed the papers by Henry Skinner on both stem and leaf bud cuttings. No one realized it at the time but of course the methods described by Skinner for making a leaf bud cutting resulted in quite a heavy wound, which I am sure had a marked effect, together with the auxin treatments, on the excellent results he reported. Next followed a visit to the Boyce Thomson Institute where both Hitchcock and Zimmerman were most helpful, and gave me copies of their published reports on the use of auxins. Then in 1939 a bulletin had been put out in England by the Commonwealth Bureau of Horticultural and Plantation Crops under the title, "Growth Substances and their Practical Importance in Horticulture", a copy of which I now obtained. In 1946 a similar publication, being a compilation of reported results from experiments all over the world, was issued by Harvard Forest. This also I obtained and was surprised to see, tucked away in the back, a short table of results reported from wounding cuttings, — the first and in fact the only table of its kind other than the work reported from Boskoop that I have been able to find.

In 1946 a fine review of all methods of propagating rhododendrons appeared in the rhododendron yearbook of the Royal Horticultural Society. Written by F.P. Knight, who was later to become the director of the R.H.S. Gardens at Wisley, this was a masterly review of all methods in use at that time and included a thorough discussion of rooting broad leaved types from cuttings. In this he reported that seventeen years earlier, i.e., in 1929, he had written an account of rooting rhododendrons with Caucasicum blood which had appeared in the Gardeners Chronicle in England. Again he reported good rooting on 'Cunningham's White' and such hybrids as 'Rosamundi' and 'Cynthia'. Despite all this published information, the commercial production of hybrid rhododendrons in both Europe and America was still by grafting.

Sometime early in 1947 I learned of the exciting results being obtained in Florida rooting cuttings under continuous mist right in the open. Such a procedure was unheard of — who would consider trying to propagate without a greenhouse or at least a frame. But apparently it was being done, and it brought home with great force the power of water in any method of plant propagation. We decided therefore to install a mist line in one of our sash type propagation houses. There were no special jets available at that time, so oil burner nozzles were used which we obtained from the Monarch Company in Philadelphia. The jets used broke up the water into an extremely fine mist and had a maximum capacity of 1½ gallons per hour, running continuously. This may not sound like much water but a 100 foot house might have 200 jets which therefore used 300 gallons per hour. After many false starts we finally set up a copper line down the apex of the roof with jets set in pairs, one pointing to each side of the house, at two feet intervals. Control was manual in the beginning, but as results began to show the value of misting, the lines were eventually controlled by time clocks and solenoids.

It was at this point that we began to sort out and assemble all the items of information gleaned from the literature. We reasoned that because rhododendrons were clearly difficult to root, if they were to be rooted successfully on a commercial scale every possible aid to rooting would have to be assembled and applied in the correct manner and order to achieve success. As a yardstick for success we defined this as at least 50% of the cuttings inserted should be well rooted, with a strong ball of roots perhaps slightly smaller than a tennis ball, and above all, well attached to the cutting. A number of people had indicated that although cuttings might be rooted statistically, yet as a practical matter root attachment was often very poor, and a plant with a large root ball growing from only one or two actual points of attachment might well have a job standing upright and surviving. Nurserymen had also found that even if own root plants grew on well, quite often when dug with a ball, the whole root system would just drop off leaving the top of the plant rootless in the digger's hand. Clearly own root plants of this type were useless.

So, starting first in 1947 and continuing for the next seven years, we began a series of experiments designed to put the pieces together in the right manner and order, and for this purpose we worked in the beginning on the comparatively easy to root variety 'Roseum Elegans'. A brief interim report was published in The American Nurseryman as part of a series of articles which I wrote covering all forms of rhododendron propagation which appeared in 1949.

Initial tests in 1947 used the so called "light wound" made by drawing the tip of the knife blade down the base of the stem for about 1½ inches. This helped, but we were working on magnolias also at this time, and testing both the "light" and the "heavy" wound we immediately found that the heavy wound was much better. The difference it made to the number of roots emerging from the cutting was astonishing, and the result was a strongly rooted cutting with a substantial root system emerging from many points. The value of this technique on magnolias was written up in an article published by the American Nurseryman in November 1949 and it is interesting to note that at that time we had completely given up grafting all varieties of this plant, and our total production of over 20,000 plants in a wide range of varieties was entirely from cuttings that year.

|

|

These are the best type of cuttings to use. Thin shoots like

this are induced by pinching before the last flush of growth. photo by James S. Wells |

The success of the heavy wound clearly indicated its possible value on rhododendrons and tests had proceeded with similar excellent results, and therefore in 1950 we tested the application of a double heavy wound on opposing sides of the base of rhododendron cuttings. The application of two wounds finally achieved what we had been looking for — a strong well balanced root system emerging from both sides of the stem and with many points of attachment. Clearly such a root system was sound in every way and subsequent development of the rooted cuttings amply proved this to be right. Tests on other items of importance had been proceeding simultaneously and as a result we were now rooting such quantities of cuttings in many varieties that we were for the first time considering abandoning grafting in favor of rooting.

The first comprehensive report governing all the many factors involved was given to the first meeting of the Plant Propagators Society in November 1951, and greatly condensed, was as follows.

1. TIMING. Suggested best time August and September.

2. TYPE OF CUTTING. Thin cuttings rooted much more readily than thick ones. Thick terminal shoots should be avoided. Thinner shoots from the side of the plant rooted more readily.

3. MAKING THE CUTTING. Shorten to no more than 3-4 inches. Remove surplus leaves retaining four or perhaps five if small.

4. WOUNDING. A heavy wound is essential cutting into the outer tissue but not into the central woody part of the stem. A double wound of this type is even better.

5. HORMONE TREATMENT. Essential. Easy varieties need IBA at .8% others will respond to strengths up to 2%. Some difficult varieties still hard to root.

6. MEDIUM. We suggested at that time 90% peat and 10% sharp sand.

7. STICKING. Do not insert the cuttings too deep. Space them so that the leaves will tend to hold each other up and clear of the bench surface.

8. BOTTOM HEAT. 70°F for root initiation. After rooting begins, development of the root system may be enhanced by lowering the bench temperature to 60°F.

9. HUMIDIFICATION. (MISTING), Essential for good results. Exact amount — duration of mist cycle — had not then been determined. We commenced with constant mist, then went to manual control and at this time were experimenting with time clocks.

10. AIR TEMPERATURE. Because of the high temperatures often experienced during August and September we argued that it might be beneficial to lower the air temperature by running a film of water down the outside of the house.

11. LIGHT INTENSITY. To be maintained at the maximum possible without damaging the cuttings.

These then were the suggestions made in 1951 and a full report was finally published in the American Nurseryman in May 1, 1953. Some refinements were noted but in broad outline the methods were as first given in 1951. The same report was also printed in that year in the Rhododendron Yearbook of the Royal Horticultural Society, and was printed in a final and complete form as part of the chapter on the propagation of rhododendrons in my Book "Plant Propagation Practices". This final report contained details of the more recent work with 2,4,5-TP and also gave in table form suggested auxin treatments for a fair range of the most hardy hybrids with which we had worked. This book is still in print, and the information on this and many other subjects is still valid.

The publication of this information finally put rooting of rhododendrons on the map, and actually in 1952, we had decided to abandon grafting and to rely solely upon rooting of stem cuttings to supply our commercial needs. Our production of cutting grown plants that year was 62,000.

There remained only one item to unravel and that was our inability to successfully root the really difficult varieties, a typical example being the variety 'Dr. H.C. Dresselhuys' Reasoning that even with all these aids to rooting we still lacked some "Punch" which would induce these tough varieties to root, — what could that "punch" be?

I turned to Beltsville for assistance and Paul Marth was most interested and helpful. After discussion he agreed that there just might be a form of some chemical, known to have root forming properties, but not generally available that might provide the stimulus we sought. He kindly made available to us a complete range of chemicals which he selected as being potentially beneficial and in 1952 we ran a wide series of tests on both 'Dr. H.C. Dresselhuys' and E.S. Rand testing all of the materials he had provided. The results were most gratifying, and with the tests completed in 1952 they were written up early in 1953 and a final report published by myself and Paul Marth in the proceedings of The American Society for Horticultural Science in 1954. This showed that a 1% mixture in talc of either 2,4-D or 2,4,5-TP rooted both varieties at 70%. Later tests showed that 2,4,5-TP was the better of the two and could produce rooting percentages up to 100%.

With the publication of these reports people began to rework and prove up the methods described, for it seemed that most were just unable to accept the fact that used as stated, the methods would work.

In 1952 Bernard Bridgers then at the University of Maryland, spent a fair part of the summer working at Koster's Nursery trying to unravel the factors involved in the successful rooting of rhododendrons. His approach then seemed to me to be entirely negative — he was concerned only with what we did not know, while I thought at the time and still think that a review and evaluation of what one does know is a much better base from which to work. His report, published in the bulletin of the American Rhododendron Society for October 1952 simply confirmed that the heavy wound we had advocated was the best. Then in April 1953 - again in the Rhododendron Bulletin - Nearing said that he had been making the "side sliced" cutting for some time. The unfortunate thing was that he had not written about it and only he and a few local friends were aware of his method which he had adapted from the leaf bud technique of Henry Skinner. It is interesting to note however that in 1954 when Fredrick Street, an English nurseryman — wrote his excellent little book entitled "Hardy Rhododendrons" he was still maintaining production by grafting, for he had achieved no better than 2% rooting. In 1957 and again in 1960 Robert Ticknor repeated experiments to compare various methods of wounding, and as in all previous occasions, concluded that the heavy wound, either a single or a double wound, was the best. In the intervening years a number of writers have described their methods of rooting cuttings, but in general they adhere very closely to the methods we developed thirty years ago. It would seem therefore that there have been few significant additions to these methods since. However we have refined our methods to some degree, and it might be appropriate to record these changes now.

1. TIMING. With a wider understanding of other factors, plus the skilled use of well constructed mist systems, this is not so critical. Our ability to root cuttings over a wide time span has slowly developed until now cuttings are being rooted from early July to late January and even February. Successful rooting of trimmings cut from large plants in April has been reported, although all agree that the period August to October is optimum.

2. TYPE OF CUTTING. Thin cuttings are still the best but again with greater skills a much wider spectrum of growth types is being rooted. It has been suggested that shoots with flower buds root less readily, but if the bud is removed they will root just as readily as any other. Thin cuttings are now being artificially produced on stock plants by pinching at the correct time.

3. MAKING THE CUTTINGS. Still essentially the same with one exception in that it is now normal practice to reduce all large leaves by half. Tests have indicated that leaves can be reduced by as much as ¾ but rooting will not be so rapid or so strong. Rooting depends more upon the total leaf surface attached to the cutting rather than whether the individual leaves are retained intact.

4. HORMONE TREATMENTS. All easy to root varieties respond to IBA at .8%. Others require 1% IBA some 2% IBA and really difficult varieties seem to respond to a mixture in either liquid or powder form of the potassium salts of both NAA and IBA .5% of each. A substantial improvement in all hormone powder treatments followed the inclusion of a fungicide. This was first reported by William Doran working at the University of Massachusetts in 1952 when he showed substantial gains by adding small amounts of Phygon XL. However greater effects were noted when Benlate became available, and it is now almost standard to add 5% Benlate to any powder in the final mix, regardless of the hormone content.

6. MEDIUMS. It seems that someone, somewhere is now rooting rhododendron in almost anything you can think of. Sawdust, shingle tow, Styrofoam, vermiculite, perlite, volcanic ash, — you name it and someone is using it. We have settled down after many tests to a standard mixture of 50% coarse Canadian peat and 50% medium grade — very few fines or large particles — of perlite. This seems to work uniformly and well.

7. INSERTING THE CUTTINGS. The same. Just do not put them in too deeply.

8. BOTTOM HEAT. Still set at 70°F and although I believe a reduction of temperature after about four to five weeks is beneficial to root development, I know of no one who is faithfully doing this, including ourselves!

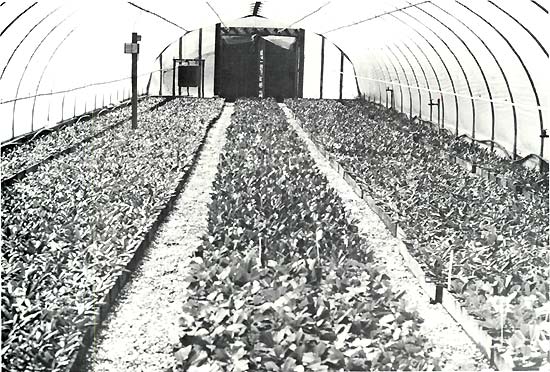

9. HUMIDIFICATION (MIST) This should now really be headed MISTING for that is what we do. Good jets are freely available and excellent time clocks. Points to watch are good coverage — make absolutely certain that there are no spots without coverage, and no blocked jets. Timing will vary according to conditions but generally we work on a six minute cycle with one, two and perhaps three bursts of mist per cycle each of 12 second duration. By and large the electronic leaf seems to have come and gone. Theoretically it is the best, yet most growers have found in practice that a good time clock working through a weaning unit will provide all the flexibility of control desired. Generally speaking we are using much more water, more frequent spurts of mist of a shorter duration and maintaining a much higher and more even level of humidity than in the beginning. It naturally follows that with so much water being applied, excellent drainage of both the medium and the bench is essential. The 50-50 peat and perlite mix provides this, but bench bottoms are now of either fine galvanized hardware cloth or saran mesh. Drainage beneath the benches must also be excellent so that excess water can drain away.

It should be noted that for the small grower or the amateur who wishes to root only a few cuttings of any plant, a mist system is not essential. There are many other more simple and equally effective methods of controlling water loss. The Nearing frame constructed and used as Mr. Nearing suggests is excellent. The only complaint I have is the time it takes to get results. Things can be speeded up if you provide bottom heat using an electric heating cable, but if this is done then the need for constant attention during the rooting period to provide water must be recognized. If you want to take advantage of the "Nearing System" but also accelerate production, it can perhaps be done most efficiently by building a good frame on the north side of a building, or on the north side of a good clump of evergreen shrubs. No sunlight must ever fall directly upon the frame, and if bottom heat is again provided by heating cables, rooting will proceed normally over a period of twelve to fourteen weeks. Good sealing of the frame should be ensured by covering both the sides and the top with sheets of polyethylene. If a frame is still too large, you can reduce things still further by using any suitable container, large pot or deep flat, filled with the right medium. Once the container is complete with cuttings it should be thoroughly soaked and then wrapped in plastic. Wire hoops over the flat will prevent the cuttings being pressed down, while in the pot a plastic bag works well. Containers of this type should then be placed on a north window sill in a warm room and left alone . The plastic will prevent water loss, and if undisturbed and given sufficient time, most of the cuttings will root.

10. AIR TEMPERATURE. In the beginning we were afraid of high summer temperatures and went to great lengths to cool the air in the house. Excessively high temperatures can of course be harmful but we now regularly expect air temperatures of 90°F to 95° when rooting the early batches and we rely mainly upon excellent coverage with a fine mist to prevent damage to the foliage. As my good friend, William Flemer, III, has said, "There simply is no substitute for the good propagator walking through the houses regularly to see what is going on". I could not agree more, and regular control and adjustment of the misting cycle to meet current conditions is a must.

11. LIGHT. Still the same. Give all you can get and protect the cuttings by the application of a film of water rather than a shade. However once again, judgment is needed, and conditions can occur when both light shading and gentle ventilation may be necessary. The danger lies in forgetting that either shading or air has been applied and moving on to less bright or less hot conditions with the cuttings still shaded. This will quickly show as rotting at the base of the cuttings, and under really bad conditions, leaf drop.

The biggest change has taken place in the form and construction of the propagating house itself. Back in the 50's we were working with the traditional low sash type propagating house, solidly built of blocks, wood and glass. An expensive structure to build, maintain, and to use, for it was most unhandy to "service". It rooted excellent plants however and we were reluctant to change. Now of course we have plastic houses usually 22 feet wide with or without the traditional benches as you prefer. Benches can be built up well above the floor, low down close to the floor or perhaps the whole floor area inside the house can be heated by polythene pipes carrying hot water from a small propane fired water heater which sits in a corner of the house. Summer cuttings of all the more easily rooted varieties are being produced in quantity by setting the cuttings directly into individual plastic pots and simply setting plastic trays of these on a well drained base in the plastic house and turning on the mist. If taken early in July rooting is usually well under way in 8 weeks, with the cost per unit substantially lower. More difficult varieties still need the help of a bench with bottom heat, but this is really only because we have run out of "summer heat" before they are rooted.

|

|

A modern mist operation plastic house with 4 mist lines.

Cuttings are placed directly into square pots to root. photo by James S. Wells |

The production of hybrid rhododendrons by rooted cuttings is now so generally understood and applied that I doubt there is any keen grower who does not know what to do. We take these systems for granted now, and before it all sinks into the mists of time I thought it might be of interest to record just what happened, where and when.

Looking back to the beginning of the series of articles I wrote for the American Nurseryman in 1949 I see that I said, in part — "I would suggest that the economic importance of the evergreen hybrid rhododendron to the average nurseryman is considerable — for it is potentially everyone's plant." And then we come to the April 15th issue of 1980 in which the American Nurseryman carried an article entitled "Rhododendrons — A Mainstay of the Garden and Nursery Industry".

Rhododendrons have come a long way in thirty years — and on their own roots, too!