JARS v38n3 - Azalea/Rhododendron Bonsai

Azalea/Rhododendron Bonsai

Ted Groszkiewicz, Marietta, GA

Bonsai for azalea and rhododendron lovers? Why not! Bonsai is for everyone, particularly in these days of shrinking and expensive real estate. Many readers of this article are no doubt awed and sometimes overwhelmed when viewing a bonsai. Yes, they are beautiful, gorgeous and in our mind's eye bring us closer to nature. Yes, they do look old; some are even ancient. From the start of this article I'll do my best to un-shroud the "mystique" which seems to surround bonsai. "Bonsai" translated from Japanese into English comes out as "tray planting". The Chinese who started this horticultural art form called it "pun ching" which is translated as "artistic pot plant." Well, there you have it. Bonsai is just a potted plant. If you have grown plants in containers outdoors you have the basic horticultural know-how to maintain bonsai. They are potted plants but with a difference. They are designed by man; the branches and trunk are more often than not manipulated (trained) into a certain style based on the natural growth habit of the plant material. Over the years bonsai has become the generic word to describe an artistically styled tree or shrub which is cultivated in a container. An appropriate definition of bonsai is an artistically designed containerized plant in miniature. All of us have a bit of the "artist" in us and you can enjoy the artist in you by designing your own bonsai from azaleas and rhododendrons.

Bonsai has its roots extending back to the days of the early Egyptians and Babylonians. It was in those ancient days that container culture of plants had its origin. This evolved into an art form in Chinese culture. There are early references to this art form in their literature around 360 A.D. A noted Chinese poet, Tou Yueming, cultivated chrysanthemums in containers. In those days the "bonsai" were on the order of decorated tray landscapes with miniature statuettes of people, animals, huts, bridges and other familiar man made objects. The styles of the trees and shrubs were extremely varied and mostly serpentine (coiled or twisted) forms. There was no correlation between the designed form and natural growth habit. Names assigned to these forms were taken from mythology, religion and infrequently from nature. The evolution of bonsai took a gigantic leap forward as an horticultural art form in Japan. Historically, this began in 1250-1375. The Japanese developed the specialized tools, sound horticultural practices and styles of design conforming to natural growth habits. With their keen insight of natural surroundings the Japanese explored and collected native plant materials which had survived the rigors of mother natures' whims and fancies. These collected plants became prize possessions. Based upon observation and cultivation of these early collected plants they developed a list of varied styles - all based on natural growth habits under ideal and adverse conditions. The designs were asymmetrical since this is the norm in natural forests. (Asymmetrical design is beyond the scope of this article. I have included a reference source at the end of this article if readers desire to pursue this subject.) In time all prize bonsai material had been collected but the Japanese ingenuity prevailed. Bonsai nurseries flourished and were able to provide plant material for bonsai enthusiasts. Along with the development of tools the Japanese are credited with initiating the wiring techniques used to hasten the creation of a bonsai. Bonsai soon became a national art-hobby in Japan. Not to be outdone the Chinese introduced a new technique about 1900. This was called the "grow and clip" method which was inspired by the Chinese brush painting technique. The result was miniature trees which had an ancient appearance as well as an easy movement of elegant grace. (The "grow and clip" technique is nothing more than repeated pinching and pruning during the growing season. This induces new growth with shorter internodes and forms "cloudlike" layers of foliage on branches.) The combination of "grow and clip" and "wiring techniques" truly elevated the container culture of trees and shrubs to the status of ART. These techniques are still in use today. The results are often viewed with unbelieving eyes and a sense of mystique.

As an art, bonsai is creative, interpretive, illusionary and always conveying an aesthetic quality. As a horticultural hobby, it is the growing and maintaining of bonsai over many years. It is this combination which separates bonsai from ordinary container plants. Unlike fine arts which are considered finished at the conclusion of the artists' handiwork, bonsai is a living art form and never remains static. As a living art form it has a beginning and an end. However, during its life-span there are continual changes from season to season and year to year. Along the way there are many challenges, primarily longevity. Your skills in horticulture and in design will be taxed in maintaining the original design or a change in design and the continued healthy growth of the bonsai.

There really are no secrets concerning bonsai. The "mystique" has come about over many years due to the unavailability of written information in the English language. All the written information was either in Chinese or Japanese. The early transliterations were often riddled with errors due to language differences. There are now excellent writings available on bonsai in the English language - some translated from Japanese and some written by English speaking authors. I have listed some of the available material at the end of this article. There is one caution when reading literature concerning bonsai. Most books or articles are written in reference to a particular locality - usually the author's. Be aware that there are differences - vast differences in climate zones in the United States. Annual rainfall is another consideration. This is important when formulating a growing medium for bonsai. I'll attempt to dispel some of the so called mystery surrounding bonsai. The following will be specifically applicable to azaleas and rhododendrons but can also apply to other plant material. In the natural order of plant growth fruit and flower size cannot be reduced by bonsai techniques. This does not mean that only genetically dwarf azaleas and rhododendrons are suitable for bonsai. The problem with genetically dwarf plant material is its very slow growth and it would take a lifetime to attain a prized bonsai. On the other hand did you ever see a sugar maple, southern magnolia or white oak as a bonsai? The leaves are much too large to reduce satisfactorily. So, one of the mysteries is the selection of azaleas and rhododendrons which when containerized will be in good proportion or scale of foliage size to flower size. As a general rule leaf size can be reduced by one half to two thirds, depending on variety. With experience you will have a keen eye and an ability to visualize the aesthetic impact of the planting on the viewer. That in itself is another so called secret - the ability to visualize the designed bonsai, plain and simple experience plus the little bit of artist. That's fine, you say but how can the plant live in one to two inches of soil in a confined container. There is no secret here. If you've grown plants outdoors in containers you know that at some time the container gets filled with roots. What do you do? Usually, you shop around for a larger container. Before long you may not be able to lift the container or if you do you're a candidate for a hernia. There is a much easier and practical approach. You remove the azalea or rhododendron from the container and prune the roots about one third. You cut heavy roots more drastically. The object here is to have a root ball composed of very fine hair roots to supply nourishment to the bonsai. You clean your container, use a fresh soil mixture and repot the azalea or rhododendron in the same container. Contrary to popular opinion the pruning of roots rejuvenates the growth of the plant. It does not injure nor does it dwarf the plant. It does slow down growth. You cannot be squeamish when it comes to pruning roots. It is an annual adventure on all young bonsai. As the azalea or rhododendron matures natural growth will slow down and the root pruning and repotting need not be done each year. You will have to inspect the root system each year to make the decision on repotting. That's great. But how about the top growth. No secret here either. Periodically you probably prune and shape your rhododendrons and azaleas in the garden. The same holds true for the bonsai plantings. However, with the plants in small containers and artistically styled you prune to maintain the original design barring such accidents as broken limbs or occasional die back. Your pruning will be more selective with an insight toward next year's growth and aesthetic presentation. Right about now you are thinking it is a lot of work. You are right and you are wrong. The major part of the work is done at the first styling or designing of a large garden specimen azalea or rhododendron. This is usually done in late February through May. You'll lose the flowers the first year but what a surprise the following year. The work is not physical labor (except for the digging); most of the work consists of pinching and pruning at the correct times of the year. Bonsai do require care, but not necessarily "tender loving care." There are more bonsai in plant heaven as a result of too much attention than pure neglect. The human tendency is to over water, over fertilize and overlook the natural needs of the plant which are fresh air (don't smother it in an indoor environment) and lots of organic material in a free draining soil mixture with frequent but very diluted application of fertilizer. As you may have noted - no mystery is involved. You are almost guaranteed to achieve success if you:

1. Select azaleas and rhododendrons which will have flowers in scale to foliage.

2. Visualize the design and aesthetic quality of the plant material.

3. Root prune to maintain same size root ball.

4. Prune top growth to maintain original design.

5. Water only when necessary.

6. Use diluted fertilizer.

7. Provide a well drained soil mixture with an abundance of organic matter.

Jump in, the water is fine. You'll enjoy it and soon will have an admirable bonsai. But do be careful - it is infectious.

When looking for azalea varieties for bonsai most enthusiasts turn to the Satsuki group. This is understandable since most pictures of azalea bonsai are Satsukis. They do make beautiful bonsai. However, today we have many alternatives in this country. Each year brings a new crop of American hybridized azaleas and rhododendrons. Most of these efforts are in the introduction of landscape plants. But among the various hybrid groups there are many that possess qualities of superb bonsai. Following is a list I have compiled of a few of the American hybrid evergreen azalea groups which seem to have bonsai potential. The list is by no means all inclusive. I have listed only those I have observed or those with which I have had experience in growing and designing. In a few instances choices were made from descriptions from experienced growers.

GABLE AZALEAS

Barbara Hille, Campfire, Rosebud, Lorna, Rose Greeley.

GLENN DALE AZALEAS

Refulgence, Eros, Helen Fox, Wildfire.

BACK ACRES AZALEAS

Cora Brandt, Red Slippers, Pat Kraft, Fire Magic

SHAMMARELLO AZALEAS

Desiree, Elsie Lee, Helen Curtis, Red Red, Hino White

NORTH TISBURY AZALEAS

Susannah Hill, Alexander, Marilee, Matsuyo, Wintergreen

BELTSVILLE DWARF AZALEAS

Little White Lie, Pink Elf, Snowdrop, Pequeno, Ping Pong

LINWOOD AZALEAS

Hardy Gardenia, Opal

ROBIN HILL AZALEAS

Wee Willie (V2-10), Christie (T21-2), Pat Erb (T36-3)

I am quite certain that many more suitable azaleas for bonsai exist in the groups listed above and in other hybrid groups not listed. Half the fun is searching out what catches your eye. There are many choices. Your critical "artistic" eye will encourage the challenge of growing an azalea or rhododendron bonsai. Your selection of azalea or rhododendron plant material should be based on its adaptability to your local climate zone. Those I have listed do well in Marietta, Georgia. That is about 12 miles northwest of Atlanta, Georgia. I've been told that the Atlanta metro area is in Zone 8. After almost 20 years in this area my impression is that Zone 6 or 7 hits in winter and in the summer it is Zone 9 or 10. Whatever happened to Zone 8! No wonder azaleas and rhododendrons have a tough time in this geographical area.

I hope readers will forgive me for not mentioning varieties of rhododendrons. My experience with rhododendrons as bonsai has been very limited. The limitation is mostly due to geographic location and the lack of success with the varieties I have tried as bonsai. In all honesty I have a greater affinity for azaleas. Currently I am trying some native deciduous azaleas for bonsai and at the same time hybridizing evergreen azaleas specifically for bonsai.

I have mentioned asymmetrical design earlier but failed to mention that the Japanese invoked the "rule of thirds" along with asymmetrical design. This rule indicates that a bonsai is never planted in the exact center of a container except for a round or square container. Most bonsai containers are either rectangular or oval and the plant is placed either one third the distance from front to back and side to side. Other guidelines were established based on the "rule of thirds" such as the relationship of the size of the container to the plant. These guidelines indicate that the length of the container should be two thirds the height of the plant and the width of the container should be one third the height of the plant. The depth of the container should be two thirds the diameter of the trunk at soil level. Other guidelines indicate that the first and dominant branch of the plant should be one third the height of the plant above the soil surface of the container. Further, that there should be three main or major branches on the plant - one to the left another to the right and a third in-between the two pointing to the rear for a three dimensional effect. These are just guidelines used in the design of the bonsai. Much depends on the availability of branches on the plant material. It is interesting to note that the "rule of thirds" was adopted because of the resulting eye appeal and its aesthetic quality. The remainder of the article will concern itself with creating an azalea or rhododendron bonsai.

There Are Three Choices In Selecting Your Plant Material

1. Dig up relatively old specimens from a garden.

2. Purchase suitable material from a plant nursery.

3. Grow your own. This is the most rewarding approach.

Criteria For Bonsai Plant Material

1. Roots spreading radially from a heavy trunk base (crown).

2. Trunk tapering from a heavy base to its apex (highest point on the trunk except for cascade).

3. Branches should be sufficient in number for design selection and ideally should range from heaviest near base of trunk to lightest near apex. Branches should also radiate in all directions.

4. Flowers of clear bright color and leaves in scale with flowers.

5. Start with a young plant 2-3 years old.

Basic Styles

1. Upright (straight trunk).

2. Informal (curved trunk to right or left but apex over center of trunk base).

3. Slanted trunk (either right or left with apex either to the right or left of the trunk base).

4. Cascade (trunk either below bottom of container or no lower than bottom of the container).

Training A Young Azalea Or Rhododendron For Bonsai

Note: It is important to cultivate a young azalea/rhododendron with a single trunk to a desired height of 16-25 inches by pruning young shoots close to the trunk during the growing season. Be certain to trim off all shoots arising at or near the base of the trunk.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

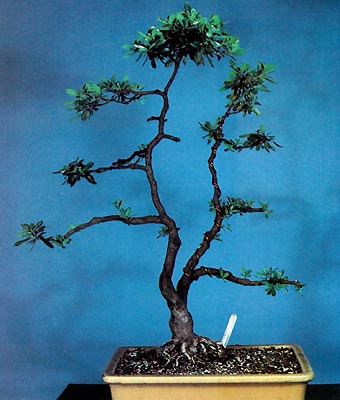

Wakaebisu Young plant wired for desired form Photo by Ted Groszkiewicz |

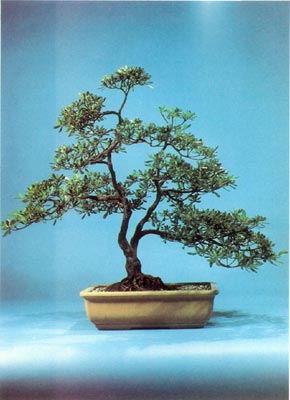

Wakaebisu Age: 16 years Height 23 inches Photo by Ted Groszkiewicz |

A. Wiring For Training

At 2-3 years of age the trunk should be wired into the desired position for your design. The trunk is still flexible enough so it won't break. Smaller desired branches can be wired at anytime during the year. Do not wire main branches or trunk during mid-winter (December, January, February). They are most brittle during these months. The best time to wire the main branches and trunk is March, October and November. Aluminum wires should be used in wiring. Aluminum is softer than copper and will not damage the tender bark as readily. Use a length of wire at least 30% longer than the branch or trunk you are wiring. Wire should be applied in 45 degree spirals. Spirals should be close together if much bending is necessary. Spirals can be further apart if bending is at a minimum. Sometimes two or even three wires are applied separately but wound parallel close together for added tension in bending large diameter trunks or branches. Wire should be snug, gently hugging the trunk or branch (not too loose nor too tight).

If the bend in the trunk or branch is to the right, wind the wire clockwise. If the bend is to the left, wind the wire counter clockwise. Wire should pass over the outside of the desired curves. The shape of the branches and the trunk must be in harmony. A straight trunk with straight branches; curved trunk with curved branches. The tips of all side branches at lower levels should be turned up slightly. At the same time the tips should be pointed slightly forward.

B. Care After Wiring

Apply some sort of protective covering for areas where unwanted branches were removed. You can use a tree seal product, rubber cement, white glue, cut paste with hormones (Japanese product), Kyonal (Japanese product composed of beeswax and hormones) or damp sphagnum moss taped over the wound with electrical vinyl tape.

Avoid direct sun for at least 2 weeks. Trees wired in October or November should have cold frame protection during the winter. Protection from cold drying winds is especially important. Do not water when root ball in containers is frozen; water only during mid-day when root ball thaws. Be certain to water thoroughly before onset of freezing temperatures.

C. Removing Wires

Remove wires when they become too tight. Usually 3-4 months during periods of rapid growth; about 5-6 months during winter (October, November) wiring. It may be necessary to rewire young trees for two-three years before desired shape is retained. Wires are removed by cutting spirals close to the trunk or branch with wire cutters. The wire sections are removed gently so as not to injure the bark. Forcing the wire off could damage the trunk or branch. Do not uncoil the wire - this is dangerous and you could easily break an un-replaceable branch.

|

|---|

Wakaebisu Photo by Ted Groszkiewicz |

Trimming Azalea/Rhododendron Bonsai

Depending on rapidity of growth it may be necessary to trim or prune the plant three times a year. Early spring (March-April) around the buds new shoots will start to grow and it is necessary to keep these from overgrowing. Remove shoots growing upward and downward on branches. Remove all shoots growing from the base of the plant. Shorten long new tip growth on all branches.

After flowering (June, no later than July 15), the new shoots growing up should be cut short and shoots facing downward removed completely. Each branch should be trimmed leaving only two shoots and two leaves on each shoot. Prune unwanted portion just above second leaf. Rewire branches if necessary and repot into fresh soil after pruning roots by about one third. NOTE: If a new soil mixture is to be used (different from that in which the plant was growing) it is advisable to remove all soil from the roots at this time. Use a gentle flow of water and a soft toothbrush to clean the roots. Make certain to fill in all spaces between roots with the new soil mix.

Fall (October-November): Do not trim or shorten branches at this time. Either remove the branch entirely or not at all.

Fertilizers

The following is an acceptable organic fertilizer:

6 parts cottonseed meal

2 parts bone meal

1 part blood meal

Use at a rate of 1 teaspoon per 2-4 year old plant once a month in March and April and again in July and August. If you are growing in a greenhouse you can fertilize all year by reducing the quantity of fertilizer to 1/3 teaspoon per month.

A liquid fertilizer such as Miracid or equivalent also works well. It is used at the rate of 1/3 tablespoon per gallon of water at each watering throughout the growing season.

Do not fertilize for one month after repotting; then gradually resume normal fertilization.

Soil

To maintain good health in bonsai azaleas and rhododendrons the container soil should meet the following recommendations:

1. Retain moisture without being soggy, permit good aeration and have excellent drainage.

2. Provide essential nutrients for good health but not promote robust growth.

3. Have a pH of about 4.5 to 5.5 There are probably as many good soil formulations as there are growers of azaleas and rhododendrons. I suggest you find one that does well for you in your area and stick with it. All good bonsai growers sieve their soil to remove all fines. This is to prevent compaction of the soil in the container and improve drainage. For what it is worth I use the following soil mix for propagating, growing on and for bonsai. This mix is used only for azaleas, rhododendrons and other broad leaf evergreens requiring an acid soil. Please note adjustments used for growing in bonsai containers:

2.5 quarts perlite

1.0 quart calcined clay (Turface or unadulterated cat litter)

1.0 quart Canadian sphagnum peat moss

5.5 quarts pine bark humus (ground pine bark with fines removed. Any ground evergreen tree bark, well composted, will serve this purpose)

Notes

Perlite is not sieved. All other ingredients are sieved. Growing mix particle size is 1/2 inch to 1/16 inch. Bonsai container particle size is 1/4 inch to 1/16 inch. Perlite is replaced by granite grit in the bonsai container mix. The granite grit is sieved to eliminate all fines. Particle size of granite grit is approximately 1/8 inch to 1/16 inch, about half and half. Commercial grades of granite grit used are labeled Starter and Grower.

The above formulation will yield 2.5 gallons of soil mix which would be sufficient for several bonsai containers. To this (for growing on and bonsai soil mix) I add the following:

½ Tablespoon calcium sulphate (gypsum)

½ Tablespoon dolomitic limestone

1½ Tablespoon fertilizer (dry) mentioned above

2½ Tablespoons composted cow manure 1-1-1

Bibliography

Bonsai Techniques I and II, John Yoshio Naka

Bonsai Techniques For Satsuki, John Y. Naka, Richard K. Ota and Kenko Rokkaku

(Available through Bonsai Institute of California, P.O. Box 78211, Los Angeles, CA 90016)

Miniature Trees and Landscapes, Yuji Yoshimura and Giovanna M. Halford

(Published by Charles E. Tuttle Co., Rutland, VT.)

Bonsai "Culture and Care of Miniature Trees" ( A Sunset book) (Published by Lane Publishing Co., MenloPark,CA94025)

Bonsai Trees And Shrubs, Lynn R. Perry (Ronald Press, New York, N.Y.)

Handbook On Dwarf Potted Trees (The Bonsai of Japan)

Handbook On Bonsai: Special Techniques

(Available through Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11 225)

Periodicals

American Bonsai Society, Inc. Box 358, Keene, N.H. 03431

International Bonsai, The International Bonsai Arboretum, 412 Pinnacle Rd, Rochester, N.Y. 14623

Bonsai Clubs, International, P.O. Box 2098, Sunnyvale, CA 97087

Design:

The Encyclopedia of Judging and Exhibiting - Floriculture and Flora Artistry, Esther Varamae Hamel