JARS v38n4 - A Gardener's Dwarf Rhododendrons

A Gardener's Dwarf Rhododendrons

Felice S. Blake

Kallista, Victoria Australia

Reprinted with permission from Bulletin of the Alpine Garden Society

It has been written that "We feel sure it would not be incorrect to say that dwarf rhododendrons are the backbone of the alpine and peat garden..." (in the now out of print A.G.S. publication Ericaceous and Peat Loving Plants ). In recent times it was noted with great interest that at the Alpines '81 Conference Show against tremendous competition the Farrer and Forrest Medals were awarded to Rhododendron keiskei 'Yaku Fairy'. This marvelously floriferous prostrate rhododendron of comparatively recent raising seems to have dominated the world of dwarf rhododendrons since it received the Award of Merit in 1970. Many would say rightly so as it possesses all the best attributes of a dwarf alpine. But what of the host of other delightful rhododendrons which so many of us grow, flower and enjoy in our gardens?

However, to begin with, we have the problem of definition - what is a dwarf rhododendron? If we consult the Oxford Dictionary, we find "dwarf" defined as:

1. Person, animal, or plant, much below ordinary size of species - (that's no help, what is the ordinary size of a rhododendron?).

2. Small supernatural being in esp. Scandinavian mythology skilled in metalworking (that, too, isn't any help!).

3. adj. Undersized (in many plant names); puny, stunted (what rot - at least where rhododendrons are concerned).

4. v. t. Stunt in growth, or in intellect, etc.; make look small by contrast or distance.

Well, the dictionary doesn't really help us very much, so let us look at some of the famed growers and authors of works on the genus. At one end of the scale Peter Cox in his work Dwarf Rhododendrons treats dwarfs as those rhododendrons which grow up to 2 m. in height in the east of Scotland - that doesn't really help us very much either, as the six footers would not be suitable for a rock garden, and in any case would probably grow to 3 m. or more here (in the Dandenong Ranges about twenty five miles east of Melbourne, Australia, in an area generally congenial for growing rhododendrons). Then at the other end of the scale the well known and so very knowledgeable grower, the late Captain Collingwood Ingram, V.M.H. who gardened in Kent, when writing of dwarfs in the Rhododendron and Camellia Year Book (1969) refers "in particular to the species and their varieties which in Nature rarely or never exceed one to two feet in height". His collection at that time exceeded well over a hundred different species and forms, and it is interesting to note that he grew his dwarfs in two raised beds, neither of them much larger than a full sized billiard table. But as Captain Ingram considered that R. trichostomum , strictly speaking, cannot be regarded as a dwarf as it eventually attains the height of a meter or so, I feel that one must seek a more generally acceptable definition.

In my opinion, after growing dwarfs and semi-dwarfs for a number of years, I would venture to classify a dwarf rhododendron as one which, planted as a two or three year old specimen, will not exceed the height of, say one meter in about ten years, but the prime consideration is that the rhododendron should look in character with its surroundings, whether it be in a specially raised bed, a peat garden, or a small or large rock garden. One often sees R. yakushimanum listed as being suitable for a rock garden, but unless one is lucky enough to acquire one of the very small growing clones, I feel that one needs a very large rock garden to accommodate this beautiful species.

The majority of dwarfs come from the high alpine regions centered on the Himalayas, with a few coming from the European Alps, northeast Asia down to Japan, and fewer still being found at low levels in the arctic regions being circumpolar in distribution and stretching down to the high mountains in western North America. And who knows, there may be more yet awaiting discovery. 1

The majority of dwarfs are lepidote, that is to say that they are characterized by scales of various shapes and sizes on their leaves, and stems, and sometimes on the calyces and corollas. There are very few dwarf elepidote rhododendrons, that is those rhododendrons where the scales are absent.

In the new Cullen and Chamberlain classification of rhododendrons, the lepidote rhododendrons are now included in subgenus Rhododendron and sections Pogonanthum and Rhododendron, whilst some elepidotes are included in subgenus Hymenanthes, and the old Azalea Series has not yet been revised by them. However, the old Azalea Series, subseries Obtusum (which includes most dwarf evergreen azaleas) was reclassified by Sleumer as subgenus Tsutsia section Tsutsia. But it is open to debate as to whether we should accept, at this point of time, the new classification, as it has obviously not been universally and internationally accepted by many experts, and vehemently opposed by some. Those of you who have "explored" Mr. H.H. Davidian's monumental new book Species of Rhododendron Vol. 7: Lepidotes will agree with many of his arguments against the new classification, whilst we, mere gardeners, do not like to see many of our favorites sunk into synonymity or changed in name by the new classification.

There is a truly enormous variety of flower form, colour and size in the dwarfs together with a great variety of leaf form, colour and size. Some species have attractive new foliage, whilst others have beautiful flaking bark, and these combinations make for year round interest. The flowering period covers many months from the early blooms of R. moupinense and R. leucaspis beginning the season in mid to late winter until R. hirsutum and its near relatives flower in high summer. As R. lepidotum , in its purple form, always makes a good show in autumn (as well as spring), plus a sprinkling of lapponicums also at that time of year, you can appreciate the worth of dwarfs in the garden. The flower forms are particularly fascinating when one considers the perfect miniature trusses of R. trichostomum , the delightful little thimbles of R. campylogynum , even more thimble-like in the form myrtilloides , and also in R. pumilum - Kingdon Ward's "pink baby", the dancing butterflies of R. lepidotum , R. keleticum and R. radicans , the sheets of glowing colour provided by the lapponicums and azaleas, not forgetting R. keiskei 'Yaku Fairy' with its "pools of moonlight". These dwarfs are very much at home in the rock and peat gardens, raised beds, troughs, pots and pans, and can also be used as a foreground to the larger growing species.

|

|

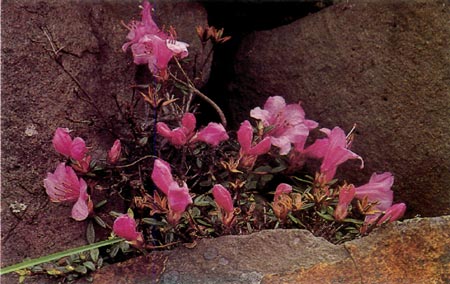

R. radicans

Photo by Art Dome |

Although the dwarfs are on the whole very hardy, it would seem preferable to try to plant them where they are protected from the hot afternoon sun in summer - but this does not mean that they should be planted under trees. They grow better in an open position, for too much shade tends to draw them up whereas in the open they will stay much tighter and more in character with the way they grow in the wild. In other words, for the more "touchy" varieties, protection from trees a little distance away can be desirable if, in your area, you experience hot afternoon sun in summer. And although the climate is different in my country to that experienced in England, I do recall, rather vividly, when visiting England in 1976, the results of that long, oh! so hot summer. Good drainage and mulching help to keep the plants in good health, and they enjoy an acid soil with peat and leaf mould incorporated in it, in slightly raised beds such as you would find in most rock gardens. For the more difficult varieties, in our climate, I find that a raised peat bed seems to be the answer, and species such as R. ludlowii , lowndesii and lepidotum var. elaeagnoides are thriving. Watering is usually imperative in summer, for they are generally shallow rooted and the root systems need to be kept cool. Although we cannot provide the conditions that are found in nature, we can learn a lot from the way they grow in the wild.

|

|

R. lowndesii

Photo by Art Dome |

Perhaps we can briefly skim through the series (or subsections if you like), but I do not think that a catalogue of names only is very helpful. Those who wish to find out more about these delightful little plants can find many reference books to help them, and the keen grower will take every opportunity to increase his or her collection.

It is interesting to note that the old Anthopogon series is now, according to Cullen, Subgenus Rhododendron, Section Pogonanthum, virtually separated from the other lepidotes. And rightly so too: they are really a race apart. This section contains some most distinctive species. I am sure all of you are familiar with R. trichostomum in its varieties ledoides and radinum . However, how many really know the difference between the two varieties? In var. radinum the corolla is densely scaly externally, whilst in var. ledoides the corolla is not scaly. As Peter Cox writes, this is a very poor distinction horticulturally. And as some people do not realize, the distinction is not on a colour basis. Included in the forms I grow is R. trichostomum var. ledoides F.C.C. Collingwood Ingram clone which is a beautiful pink with a much larger than usual truss. Also in the anthopogons we have R. anthopogon itself, but we are finding here in the Dandenongs that it is very slow to flower, and several forms including 'Betty Graham' imported some years ago are still disappointing in that respect. Among the yellows are R. hypenanthum 'Annapurna' (now relegated by Cullen to a subspecies of R. anthopogon ), and R. sargentianum , and very charming they are too. The clone of R. sargentianum named 'Whitebait' is more commonly grown, but it is cream, not yellow, although certainly more hardy and more easily propagated than the yellow form. The loveliest in this series must surely be R. cephalanthum var. crebreflorum with its flat faced shell pink flowers which show to great advantage against the dark foliage, but unfortunately again this is not the easiest to grow to flowering perfection here, and neither is the much sought after R. kongboense . Also in this series is R. primuliflorum var. cephalanthoides which flowered for me for the first time last spring, and is a delightful rose pink, and only four years from a cutting. I also have very small plants of R. collettianum and R. laudandum var. temoense , and am waiting with eager anticipation for the day when they will eventually burst into bloom.

In the Edgeworthii series, R. pendulum is worth a place in the dwarf collection; although it is supposed to grow to over a meter, so far it has been very slow growing. The foliage is most interesting, with woolly brown fluff under the leaves, and silvery above, particularly in the new growth, and so makes a good contrast to other dwarfs. My largest plant is now in bud although only about 25 cm. high.

The large Maddenii series provides us with two yellows, a very desirable colour among dwarfs - R. valentinianum with bristly hairy leaves, bronzy new foliage and bright yellow flowers, and the slightly bigger R. fletcherianum , in its best form 'Yellow Bunting' with primrose yellow flowers. It is interesting to note that Davidian has included these in the "new" Ciliatum series, although retained by Cullen in subsection Maddenia "Ciliicalyx Alliance". It is no wonder that we poor gardeners are getting very confused!

The Moupinense series (or subsection Moupinensia) gives us one really beautiful species, R. moupinense itself, both in the white flushed pink form, or more preferably in the deep rose form - it is early flowering and extremely lovely, but being early flowering it usually requires a little protection.

|

|

R. tephropeplum

Photo by Art Dome |

Although we usually associate the Triflorum series (subsection Triflora) with large growing plants, the series provides us with one of the most fascinating of dwarfs, R. keiskei . The form grown for many years here in the Dandenongs is the larger one which grows to a meter or so high and nearly as much through - a very beautiful plant with clear yellow flowers but only suitable for the larger rock garden. However in recent years a number of other forms have come into cultivation the most famous of which is, of course, the renowned 'Yaku Fairy', but other small growing forms are also very charming. R. hanceanum nanum used to be included in the Triflorum series, but Cullen, in his wisdom, has now included it in a new subsection Tephropepla together with R. xanthostephanum , R. auritum and R. tephropeplum itself, but Davidian has retained it in the Triflorum series, Hanceanum subseries. Whilst R. hanceanum var. nanum is of ideal stature for the dwarf collection I feel that both R. xanthostephanum and R. auritum , also some forms of R. tephropeplum grow too big too quickly to be included, but the narrow leafed form of R. tephropeplum with its tubular campanulate pink flowers is always welcome in the rock garden. Those species still left in subsection Boothia, the old Boothii series, include the invaluable early flowering R. leucaspis with its milky white flowers enhanced by chocolate stamens, and the beautiful yellow flowered R. megeratum . Both these species require a little more protection than some of the other hardier dwarfs. Also in this subsection or series is the yellow flowered R. sulfureum , but perhaps this is a little big for all but the rather large rock garden.

In the Scabrifolium series, now subsection Scabrifolia, we find R. racemosum , a very well known dwarf, particularly in the Forrest 19404 form with bright pink flowers, and fairly small growing in comparison with other forms. The lighter pink clone 'Rock Rose' (being Rock No. 59578) is a very lovely plant and my personal choice in the "racemosums". It is bigger growing that the Forrest form and therefore more suited to background planting unless judiciously pruned from time to time. There is also a beautiful white form, pale pink in bud, but eventually a bit too big.

In the Lapponicum series (subsection Lapponica) we find that the overwhelming majority are in the mauve purple colour range, very generous in their flowering, absolutely indispensable in the rock garden and mostly very hardy and sun tolerant. R. scintillans (now re-classed as R. polycladum Scintillans Group) is almost royal blue in its best forms, R. russatum , a little larger in flower than most Lapponicums, is deep purple, and in the colour breaks of yellow and white we have R. flavidum and R. chryseum (now R. rupicoia var. chryseum ) both yellow flowered, and white is represented by R. microleucum (now R. orthocladum var. microleucum ) and also by the albino forms of R. chryseum and R. flavidum . Among the taller growing lapponicums is, of course, R. hippophaeoides , with its lovely lavender blue flowers but suitable only for background planting. The foliage in most of the species is tiny, particularly in R. telmateium , R. stictophyllum , R. edgarianum and R. tapetiforme amongst others; some turn rich colours in winter, particularly R. dasypetalum , and some have lovely glaucous foliage such as R. fastigiatum . A form of R. litangense (now included with the indispensable R. impeditum , but to me quite different) which I obtained some years ago is a delightful plant with quite large light blue flowers. and is one of my favorites in the series. There are many more well worth growing including R. intricatum and R. lysolepis (even if some of the botanists now claim this is a hybrid), the choice usually being dependant on the space available. If you have a bed of lapponicums and are not too much of a purist, a planting of the hybrid R. 'Chikor' looks very much in keeping, and makes a good foil for the blues, mauves and purples.

|

|

R. hirsutum

Photo by Art Dome |

The few European dwarfs which were formerly included in the Ferrugineum series are in the new classification included in genus Rhododendron, subgenus Rhododendron, section Rhododendron, subsection Rhododendron, reminds one that this is where the story of rhododendrons began. R. ferrugineum , the type species of the genus, the Alpenrose, ranging from the Pyrenees to the Austrian Alps is well known, as is R. hirsutum on limestone in the central and eastern Alps, and R. myrtifolium (formerly known as R. kotschyi which name is still retained by Davidian) coming from the more easterly parts, that is the Carpathians, Bulgaria and Yugoslav Macedonia. These are late to flower, so they really need a place where the flowers can survive the hot summer sun. I am particularly fond of the double form of R. hirsutum , a most charming and free flowering plant, and a form of R. kotschyi which flowered for the first time last year and is a fascinating luminous pinky amethyst shade - an import from the U.K. several years ago.

Included in the Saluenense series (subsection Saluenensia) are some lovely dwarfs, the most widely grown being R. keleticum and R. radicans especially good in the Rock 58 form of the former, and Forrest 19919 form of the latter (but beware of the poorer forms where the flowers hang their heads, almost in shame). These two are very distinct but some forms of these species tend to merge, and now in the new classification they are lumped together and classified as subspecies of R. calostrotum which horticulturally would appear to be quite distinct - but that, once again, is the opinion of a mere gardener. One of the most beautiful species in this series is R. calostrotum 'Gigha' with almost wine red flowers and glaucous grey foliage. I also grow R. calostrotum var. calciphilum (now R. calostrotum ssp. riparium ), but this is slow to flower here. In the better forms of all these species the flowers are perched above the foliage and could be likened to dancing butterflies. R. chameunum , R. prostratum and R. saluenense are also well, worth growing, together with the late flowering R. nitens . A group of all the various species in this series looks charming.

|

|

R. imperator

Photo by Art Dome |

The Uniflorum series (subsection Uniflora) contains some gems. We all know R. pemakoense , another absolutely indispensable plant for the rock garden, which being stoloniferous will fairly quickly form a spreading mound, and in full, perfect bloom is in the Gold Medal class. R. patulum is very close to R. pemakoense , and by some experts considered synonymous. R. uniflorum is another one in this group, and a bit similar to those mentioned above. R. imperator is a little more difficult to grow than the preceding ones, but very close to R. uniflorum , and again in the pinky mauve or purplish shades. Perhaps a more peaty mix may help here. I consider the gem in this series to be Kingdon Ward's "pink baby", R. pumilum . It has very dainty thimble-like flowers of a delightful pink - at first glance one would think that it would be included in the Campylogynum series, but there is a big difference on a closer inspection. One can then realize that the style is straight, whereas in R. campylogynum the style is always bent. I am finding that this species, too, is more at home in the peat bed. The other gem in this series is the beautiful yellow flowered R. ludlowii , but unfortunately this is not always the easiest to grow, but it would seem that an almost pure peat mix might encourage it too.

|

|

R. campylogynum var. cremastum

Photo by Art Dome |

The Campylogynum series (now subsection Campylogyna) consists of one very variable species. R. campylogynum , with nodding campanulate flowers in varying shades of pink, plum, purple, white and red, a little bigger in var. charopoeum , to my mind just about the most enchanting of all the dwarfs. Most varieties form mounds from 10-60 cm. with the exception of var. eelsum which is taller. Much has been written about this species, and the late Capt. Collingwood Ingram felt very strongly that some forms are so distinct, that they should be given specific status, and went to the length of publishing what he considered to be separate species. His view has a lot of adherents. Most forms of R. campylogynum are characterized by the glaucous underside to the leaves, but not so in var. cremastum which has pale green undersides to the leaves, and really does look quite different to the other forms and was classified by Ingram as R. amphichlorum var. cremastum is variable, ranging from purple to the well known 'Bodnant Red' form. One very lovely white form is usually referred to as var. leucanthum , as suggested by Ingram. There is one form of R. campylogynum var. myrtilloides which has pink flowers and was named by Ingram as R. campylogynum var. eupodum . This has smaller leaves, and is smaller growing than most forms of var. myrtilloides . It is interesting to note that Davidian now classes var. cremastum as a distinct species - R. cremastum .

|

|

R. brachyanthum var. hypolepidotum

Photo by Art Dome |

Close to the campylogynums is the Glaucophyllum series (or subsection Glauca), and the species in this series have flowers rather like enlarged campylogynums, and are larger growing. R. glaucophyllum is more suited to the back of the rock garden, as it can grow fairly quickly - it comes in varying shades of light to deep pink. There is also a white form of recent introduction, which is not very widely grown yet. The gem of this series, to me, is R. luteiflorum which must be one of the loveliest of the smaller growing yellows. Although formerly classified as a variety of R. glaucophyllum it has rightly been given specific status in recent years. As it can sometimes die for no apparent reason, it is a good idea to propagate this every few years for replacements - it grows fairly easily from cuttings. R. charitopes is another gem and has speckled apple blossom pink flowers, but perhaps a little slower to flower than other species in this series, and one must not overlook R. tsangpoense , R. shweliense , and the yellow R. brachyanthum and its var. hypolepidotum . The Lepidotum series or subsection Lepidota contains some very challenging plants. The purple form of R. lepidotum is widely grown, hardy and most floriferous. After an abundance of flowers in spring, it obligingly flowers again in autumn, and in some years it will have a sprinkling of blooms during winter also. As I write this on a cold, wet and windy winter's day, not only can I look across my rock garden to see R. lepidotum with quite a lot of flowers still out, but also R. hanceanum and R. kiusianum album flowering still. The yellow form of R. lepidotum is another matter: it is not so easy, but a challenge to grow and flower. It is usually deciduous and some forms called var. elaeagnoides almost merge with the legendary R. lowndesii , another difficult one to cultivate. But these two seem to be responding to the peat bed environment. There is also a delectable white form with small flowers sitting high above the little bush, and also a pink form, but so far I have not been able to acquire it. Then there is that exquisite little charmer 'Pipit', a natural hybrid of R. lepidotum x R. lowndesii . If ever there was a "case" for growing hybrids surely this must be it! I first saw this treasure at the A.G.S. Spring Show in London in 1976, and after several attempts at importing it, I finally obtained it and it is a real joy. Still included in the Lepidotum series by Davidian, but now reclassified by Cullen in subsection Baileya, is R. baileyi , a quite distinctive plant with purple flowers.

|

|

R. lepidostylum

Photo by Art Dome |

To conclude the lepidotes suitable for the rock and peat gardens, we must include the Trichocladum series or subsection Trichoclada. The most important species here is, of course, R. lepidostylum . Maybe in due course it will grow a bit big, but it is a superb foliage plant, with intensely glaucous new growth, so lovely that the pale yellow flowers are really of secondary consideration. It is so easy to propagate that one can always have a replacement at hand if it outgrows its place. R. caesium is also worth growing as a foliage plant, but really not so outstanding as R. lepidostylum . Others in this series can be a bit too big.

|

|

R. caesium

Photo by Art Dome |

When we turn to the elepidote rhododendrons (or subgenus Hymenanthes) we do not find anything like the variety of dwarfs as in the lepidotes. I think that most would agree that the azalea series, subsection obtusum, contains the most "useful" species. The widely variable R. kiusianum is a "must", apart from providing sheets of pink in the season it also obliges with a lovely white form which is very valuable as whites are not so prevalent in the dwarfs. My favourite among the pink forms is 'Shoi Pink', an import from the U.S.A. some years ago. The tiny flowered R. serpyllifolium can look lovely draped over a rock or preferably over a stream or pool. The late flowering R. nakaharai is also useful, but sometimes the colour of the flowers can be a bit difficult to place, being salmon-red shades, so one must take care in choosing its neighbors. I grow two forms, one completely prostrate, and the other var. 'Mariko' being more of a rounded bush. I suppose one should include R. macrosepalum 'Linearifolium', or whatever name that curiosity goes by now, but somehow I just cannot grow it in the rock garden. I do grow it, but elsewhere. To me it lacks the necessary character needed for a rock garden. A couple of fairly recent arrivals could prove interesting, firstly R. taiwanalpinum with attractive hairy leaves and mauve flowers. Perhaps it may grow a bit too big in due course, but one will have to wait and see. The other is R. noriakianum , another one from Taiwan, this one having very tiny leaves and small lavender flowers. We must not overlook some of the deciduous azalea species such as R. canadense with its wide open rose purple, or sometimes white, flowers. Another deciduous delight which I almost hesitate to mention, as I really do not know its ultimate height, is the recently introduced and beautiful foliaged R. kiyosumense . It is a plant of great architectural appeal, with leaves in whorls at branch tips, and the plant seems to be ascending in tiers. The autumn tones are quite outstanding, and the leaves hold for quite some time. Until I can ascertain its ultimate height, it has been planted more or less as a background subject.

Foremost in the Neriflorum series (subsection Neriflora) must be R. forrestii var. repens , the despair of many of us who have spent years trying to entice it to flower. However there are definitely some free flowering forms around, so hopefully we may see more of these striking scarlet flowers on low mounds before too long. Also in this series is the variable R. chamaethomsonii , and its form chamaethauma , also scarlet, but one must be careful to acquire the small growing, small leafed forms. There is, too, a deep pink form of var. chamaethauma which is a great addition to the rock garden. Another interesting species in this series is R. dichroanthum ssp. apodectum with orange waxy flowers on a rounded bush. A bit bigger is R. haematodes , with scarlet-crimson flowers, and lovely foliage, but suitable only for the large rock garden or as a background subject.

In the Barbatum series (now subsection Maculifera) there is a most interesting introduction, from seed, being a dwarf form of R. pseudochrysanthum from Mt. Morrison in Taiwan. This seems to be rather variable, but very slow growing, so is being watched with great anticipation, as it could be a valuable addition to the dwarf rhododendron collection. After a number of years one plant is still only 15 cm. high and 30 cm. across, a very dense dome, but has not yet flowered. The quite large leaves make an interesting contrast to the other dwarfs.

From the Ponticum series (subsection Pontica), from the Siberian Mongolian mountains and Manchuria, south to Korea and Japan, comes R. aureum ( formerly known as R. chrysanthum ) which makes a prostrate to dome shaped bush, very slow at first, and eventually with cream to yellow flowers. Its variety nikomontanum from Japan is now classified as a hybrid of uncertain parentage. Quite a few local gardeners are growing this from seed from various sources, and they certainly appear alike at this stage. So we are all awaiting the day when these plants will flower for us, albeit I feel we will have to wait a long time.

I always feel that R. williamsianum (formerly of the Thomsonii series, now of subsection Williamsia), so often described as a dwarf, grows too quickly and gets too big for the average rock garden. However, it is such a beautiful plant that perhaps we should always find room for it as a background subject.

In the old Campanulatum series, but now included in subsection Lanata, is the very beautiful R. tsariense , a superb foliage plant with thick, woolly, cinnamon indumentum below the leaves and glorious new growth. Mine has not yet flowered and I am looking forward to that day. It is supposed to grow quite tall, but is slow growing and for some years could grace the rock garden with the greatest distinction. Before leaving the Campanulatum series, now included in subsection Campanulata, is the magnificent foliage plant, R. campanulatum ssp. aeruginosum , with its intensely blue new growth. Although not usually included as a dwarf, my plant about sixteen years old is still only about 50 cm. high and the same across, and as a background plant makes a wonderful foil for its companions.

A little gem is R. camtschaticum of the Camtschaticum series, unusual in that the wide open flowers are borne on the current year's growth, reddish purple or pink (or rarely white, if you are fortunate enough to obtain this form, which I have not been able to so far). This one seems to have been a puzzle even to the botanists as it has at times over the years been classified as Rhodothamnus and Therorhodion as well as Rhododendron . This is not always the easiest to grow, but again the peat bed environment seems to suit it. I see that from a note in The Rhododendron Handbook 1980, this rhododendron has now been reclassified again as Therorhodion . It seems at times difficult to keep up to date!

Finally in the species, I must include R. roxieanum , a member of the Taliense series, now subsection Taliensia. This is one of those sought after architectural rhododendrons, very distinctive with its long narrow dark leaves with fawn indumentum below. It may eventually grow too tall, but it is relatively slow growing, so one may enjoy it for a long time before it outgrows its place. Some authorities say it is slow to flower, but that has not been my experience - one plant six years from a cutting (I was rather lucky with cuttings that year) - flowered as a four year old. Another of the same age, but grafted, also flowered as a four year old. Perhaps they came from a free flowering clone, or perhaps the climate has something to do with it. Incidentally the cutting grown plant is still only 25 cm. high, and occupies the corner of a hypertufa trough. There is also a most desirable dwarfer form, var. oreonastes , this I grew, and lost, but hope to grow again.

I have not yet touched on the subject of hybrids - many alpine enthusiasts seem to look askance at hybrids, but most of us like to include some hybrids in our dwarf rhododendron collections. They can certainly add to the colour variations, and can fit in very well with the species. From my personal point of view, when planning the placement of dwarf species in my new garden several years ago, I decided to plant them in series, but it was not long before this plan began to fall apart. I found that hybrids such as 'Chikor' enhanced the planting of lapponicums where yellows are none too plentiful. Then with the campylogynums I found that the yellow 'Kim' and rose pink 'Canada' added to the interest. Many hybrids can be fascinating, look at the way R. keiskei 'Yaku Fairy' has been used to produce some lovely yellows when mated with R. ludlowii , R. lowndesii and R. luteiflorum (and possibly others we have not yet heard about) and a lovely blush white when mated with R. racemosum . Then there are those hybrids with R. forrestii var. repens as their parent, such as 'Carmen' and my own particular favourite 'Martha Robbins', where the parent can be difficult to grow and flower. One could go on at length, for there is such a multitude of hybrids. We should not overlook them, as in some cases the hybrids make much more satisfactory garden plants than their parents - we cannot all grow R. ludlowii and R. lowndesii , but we can grow their progeny with ease.

And a last word on hybrids - one of the most interesting is the bigeneric hybrid, Ledodendron 'Arctic Tern', a cross between R. trichostomum and Ledum glandulosum or its variety columbianum . This is a delightful plant with incredibly white snowball flowers a little bigger than R. trichostomum . I imported this from Scotland several years ago, and think it is a most worthwhile addition to the garden.

I wonder if I dare to mention the enticing world of section Vireya. Although these come from the high mountains of the Malay archipelago, they do require frost free conditions, but for those who can provide suitable accommodation, the vireyas (formerly called malesians) can open up a whole new world of dwarf rhododendrons. Perhaps the most widely grown is R. gracilentum from the mountains of New Guinea, with very small leaves and up to 2 cm. long cylindrical, red or pink flowers. My own favourite is R. anagalliflorum , a tiny leafed prostrate shrublet, with white flushed pink bells a little like R. pumilum . Another most interesting plant is R. stenophyllum with long, very narrow, shiny leaves, an eye catcher even when not in flower. There are many others, some not easy to grow and keep such as R. saxifragoides - I did grow this many years ago, and hope one day to have the opportunity to grow it again.

I will only touch briefly on propagation. Like most keen growers, I keep my eyes skinned closely on all the seed lists I receive each year, and always have a go at trying to obtain seeds of any interesting dwarfs (but be a bit cautious, the bumble bees have been known to fiddle about with the species. Plants raised from seed, supposedly of R. calostrotum 'Gigha' several years ago, do not resemble imported plants of this species). I use a normal John Innes type seed compost, topped with a layer of finely sieved peat. I sow the seed directly on to the peat, and I find that seed grown in a heated propagation box with mist is most helpful and the seeds usually germinate more quickly. Propagation from cuttings is easy with the majority of species and hybrids, although a few are definitely very difficult. I use a peat and coarse river sand mix, and a hormone powder: again I use a heated propagation box and mist. Most species and hybrids will root in about two months, or less, and some will flower in two or three years from a cutting. This is a very satisfying way to increase one's plants and provide one with exchange material, and plants to give to one's friends.

1 Little did I realize when a few months ago I wrote in the above article - "And who knows, there may be more yet awaiting discovery", that exciting news would come from Sikkim so soon afterwards, telling of R. setosum in richly coloured crimson, pink and purple, and R. anthopogon in pink, yellow, peach, apricot, white and cream - a foretaste of things to come...